1. Lee SG, Hwang S, Jung JP, et al. Outcome of patients with huge hepatocellular carcinoma after primary resection and treatment of recurrent lesions. Br J Surg. 2007; 94:320–326. PMID:

17205495.

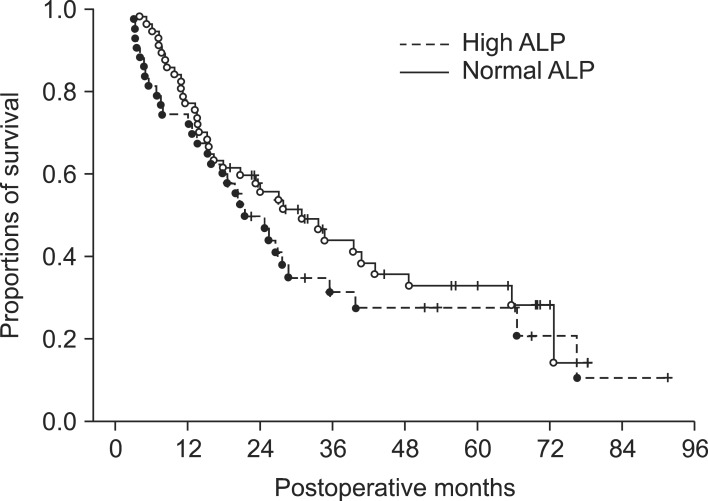

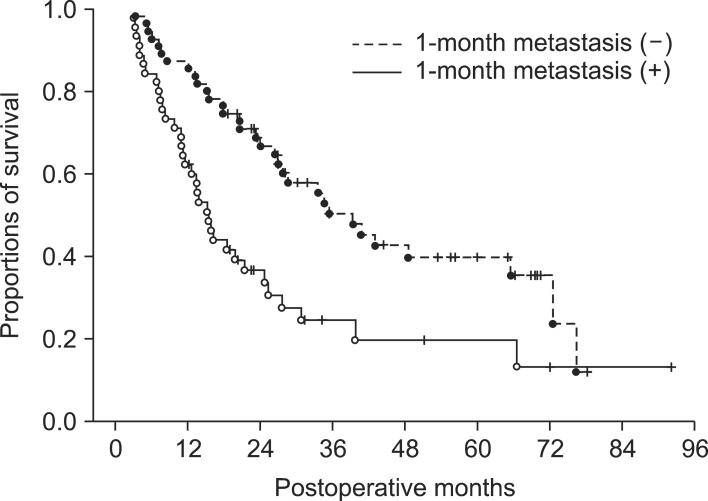

2. Kim JM, Kwon CH, Joh JW, et al. The effect of alkaline phosphatase and intrahepatic metastases in large hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2013; 11:40. PMID:

23432910.

3. Poon RT, Ngan H, Lo CM, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma and postresection intrahepatic recurrence. J Surg Oncol. 2000; 73:109–114. PMID:

10694648.

4. Mok KT, Wang BW, Lo GH, et al. Multimodality management of hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm. J Am Coll Surg. 2003; 197:730–738. PMID:

14585406.

5. Yeh CN, Lee WC, Chen MF. Hepatic resection and prognosis for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma larger than 10 cm: two decades of experience at Chang Gung memorial hospital. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003; 10:1070–1076. PMID:

14597446.

6. Zhou XD, Tang ZY, Ma ZC, et al. Surgery for large primary liver cancer more than 10 cm in diameter. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2003; 129:543–548. PMID:

12898232.

7. Chen XP, Qiu FZ, Wu ZD, et al. Chinese experience with hepatectomy for huge hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2004; 91:322–326. PMID:

14991633.

8. Nagano Y, Tanaka K, Togo S, et al. Efficacy of hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinomas larger than 10 cm. World J Surg. 2005; 29:66–71. PMID:

15599739.

9. Liau KH, Ruo L, Shia J, et al. Outcome of partial hepatectomy for large (>10 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2005; 104:1948–1955. PMID:

16196045.

10. Pawlik TM, Poon RT, Abdalla EK, et al. International Cooperative Study Group on Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Critical appraisal of the clinical and pathologic predictors of survival after resection of large hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch Surg. 2005; 140:450–457. PMID:

15897440.

11. Vauthey JN, Lauwers GY, Esnaola NF, et al. Simplified staging for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002; 20:1527–1536. PMID:

11896101.

12. Pawlik TM, Delman KA, Vauthey JN, et al. Tumor size predicts vascular invasion and histologic grade: Implications for selection of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2005; 11:1086–1092. PMID:

16123959.

13. Lou CY, Feng YM, Qian AR, et al. Establishment and characterization of human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line FHCC-98. World J Gastroenterol. 2004; 10:1462–1465. PMID:

15133854.

14. Liu ZZ, Huang WY, Lin JS, et al. Cell cycle and radiosensitivity of progeny of irradiated primary cultured human hepatocarcinoma cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2005; 11:7033–7035. PMID:

16437612.

15. Sun HC, Tang ZY. Preventive treatments for recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma--a literature review of randomized control trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2003; 9:635–640. PMID:

12679900.

16. Ren ZG, Lin ZY, Xia JL, et al. Postoperative adjuvant arterial chemoembolization improves survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with risk factors for residual tumor: a retrospective control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2004; 10:2791–2794. PMID:

15334671.

17. Chen WT, Chau GY, Lui WY, et al. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection: prognostic factors and long-term outcome. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004; 30:414–420. PMID:

15063895.

18. Choi D, Lim HK, Kim MJ, et al. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma: percutaneous radiofrequency ablation after hepatectomy. Radiology. 2004; 230:135–141. PMID:

14631050.

19. Poon RT, Fan ST, O'Suilleabhain CB, et al. Aggressive management of patients with extrahepatic and intrahepatic recurrences of hepatocellular carcinoma by combined resection and locoregional therapy. J Am Coll Surg. 2002; 195:311–318. PMID:

12229937.

20. Zhou XD, Tang ZY, Yang BH, et al. Experience of 1000 patients who underwent hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2001; 91:1479–1486. PMID:

11301395.

21. Hwang S, Kim YH, Kim DK, et al. Resection of pulmonary metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma following liver transplantation. World J Surg. 2012; 36:1592–1602. PMID:

22411088.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download