Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

The objective of this study was to evaluate the relationship between initial personal experiences with distal pancreatectomy and perioperative risk factors, outcomes, and management of pancreatic fistulas.

Methods

Between May, 2007 and May, 2010, a total of 28 patients who had undergone elective distal pancreatectomy were evaluated for this study. Perioperative factors and the occurrence of pancreatic fistula were analyzed on the basis of International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) criteria.

Results

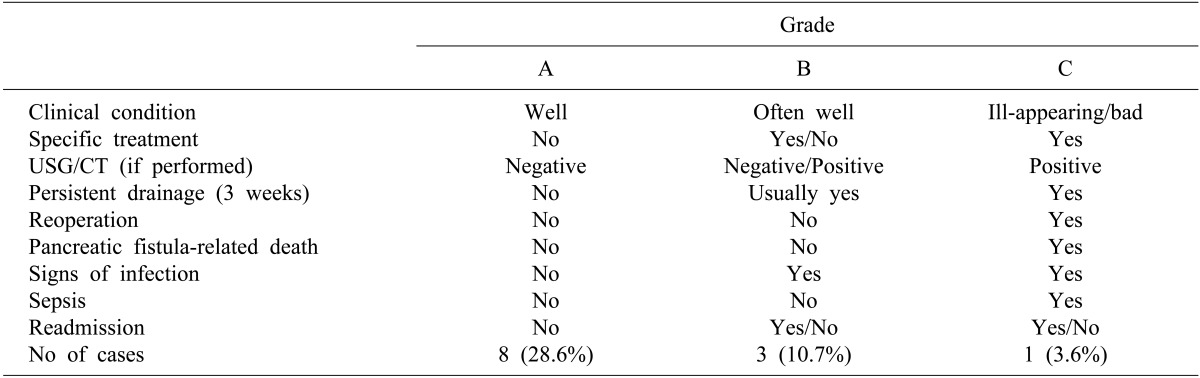

There were sixteen cases of benign neoplasms and twelve cases of malignant tumors. The remnant pancreas was manually sutured with ligation of the pancreatic duct (n=14), auto-suture stapling along with manual sutures (n=12), or stapling alone (n=2). According to the ISGPF classification, morbidity and mortality associated with pancreatic fistulas was 42.9% (n=12) and 0%, respectively. These pancreatic fistulae were classified as grade A in 8 cases (28.6%), grade B in 3 cases (10.7%), and grade C in one case (3.6%). All patients with pancreatic fistula were treated conservatively.

Go to :

Distal pancreatectomy is the standard treatment for benign or malignant neoplasms of the pancreatic body or tail. Although mortality after distal pancreatectomy has decreased to 0-6%, the rate of complications is still as high as 10-46%.123456789 Pancreatic fistula is one of the most common complications following distal pancreatectomy, and results in a poor prognosis due to the development of intra-abdominal abscesses, intra-abdominal bleeding, wound infection and sepsis.12 Although there have been many studies on determining the causative factors for pancreatic fistula, there is no commonly accepted risk factor because the causative factors are mainly dependent on the surgical techniques or the experience of the surgeons.

In the past, there were marked differences in the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula because of the various definitions applied at each surgical center. Recently, the definition of pancreatic fistula has been based on the definition provided by the International Study Group for Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF). However, the incidence of pancreatic fistula is still significantly different between surgeons because of different subjective definition of pancreatic fistula.

We herein present our early experience with pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomies, which were performed by a single surgeon who finished one-year of fellowship training in a specialized center for surgery of the hepatobiliary pancreatic area.

Go to :

From May 2007 to May 2010, a total of 28 patients who had undergone distal pancreatectomy (performed by a single surgeon) were enrolled in this study. Emergency trauma cases and pancreaticojejunostomy cases were excluded from this study.

When carcinoma of the body or the tail of the pancreas is suspected, the neck of the pancreas, which is the landmark structure for the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein, is surgically removed. The remnant pancreatic resection margin was sutured continuously using non-absorbable suture material (Prolene 4-0, Ethicon, USA) after resection was done using an auto suture device (Endo-GIA Univ. Roticulator 60-2.5, Covidien, USA, white cartilage). However, when the resection of the pancreas was done manually, the remnant pancreatic resection margin was sutured continuously by non-absorbable suture material after the pancreatic duct was ligated 3-4 times with non-absorbable suture material (Prolene 5-0; Ethicon, USA). During laparoscopic approaches, resection was done only using an auto suture device.

One of the drainage tubes was placed in the cut surface of the pancreas; the other tube was inserted in the left subphrenic region only when concurrent splenectomy was performed. A suction drainage tube (Barovac, Sewoon Medical Co., Korea) was used for drainage.

For benign neoplasms of the pancreatic body or tail, the resection margin was secured approximately 1 cm to the right side, and the remnant pancreas was managed in the same manner. Fibrin bioadhesive (Greenplast, Greencross Corporation, Korea) and hemostat product (Surgicell, Ethicon, USA) were applied to the resection margin. A somatostatin derivative (Sandostatin, Novartis, USA) was administered for seven days after the operation.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan and an analysis of drained fluid was performed on the 7th postoperative day. Pancreatic fistula was defined as an amylase level of drainage fluid greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal serum amylase levels and a drainage volume that was more than 30 cc when the drainage fluid was not serous. Furthermore, the severity of pancreatic fistula was determined based on ten clinical criteria, and stratified into three levels of impact (grades A, B, and C) according to the ISGPF definition. Grade A fistulas are transient, asymptomatic fistulas, with only elevated drain amylase levels. Grade B fistulas are clinically apparent, symptomatic fistulas that require diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic intervention. Grade C fistulas are severe, clinically significant fistulas that require major deviations in clinical management, usually in an intensive care setting.101112

The drainage tube was removed on the 8th postoperative day regardless of the amount of drainage when the drainage tube was well placed in the cut surface of the pancreas and drainage fluid was serous without abnormal fluid retention on abdominal CT on the 7th postoperative day. Even if there was no abnormal fluid collection on abdominal CT, the drainage tube was maintained in position when the drainage fluid was not serous regardless of its amount. A percutaneous drainage procedure was performed for abnormal fluid retention on abdominal CT. Also, if clinical symptoms occurred, a percutaneous drainage procedure was performed.

Patients who underwent only pancreatectomy were started on a diet on the second day after operation, even if the pancreatic fistula had not controlled after conservative management.

Go to :

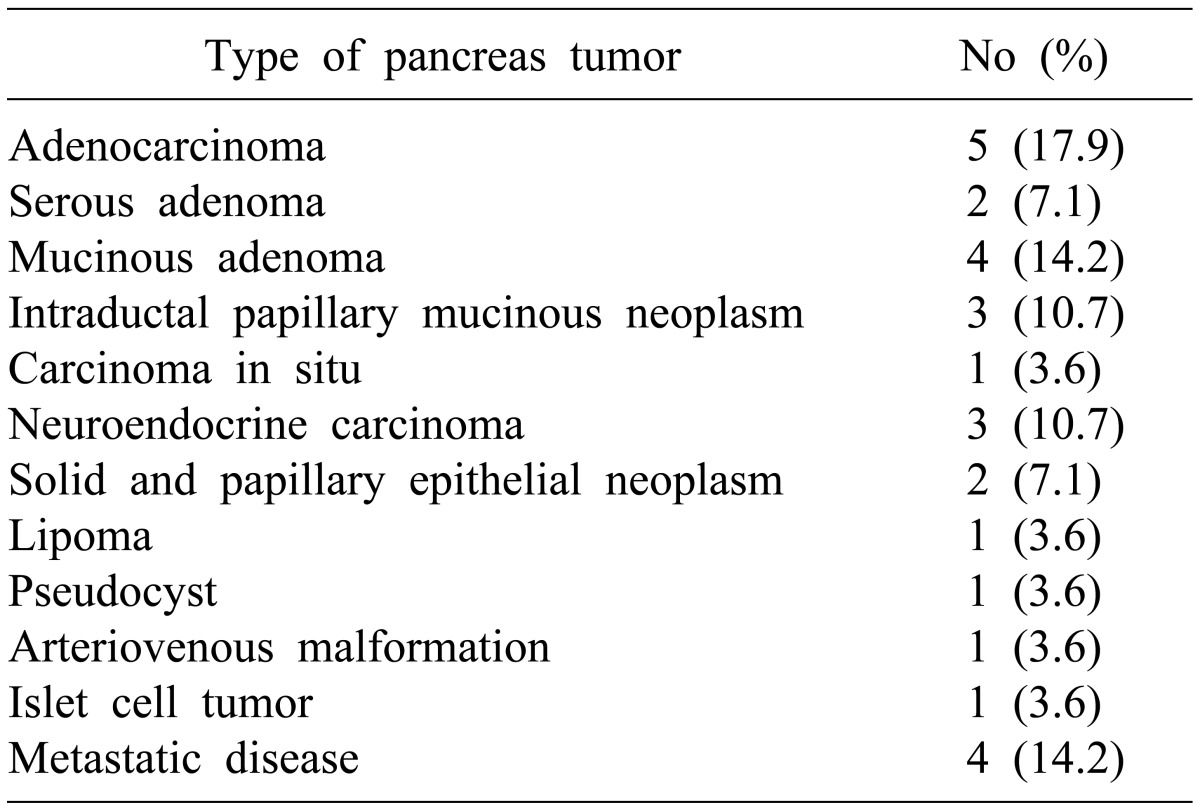

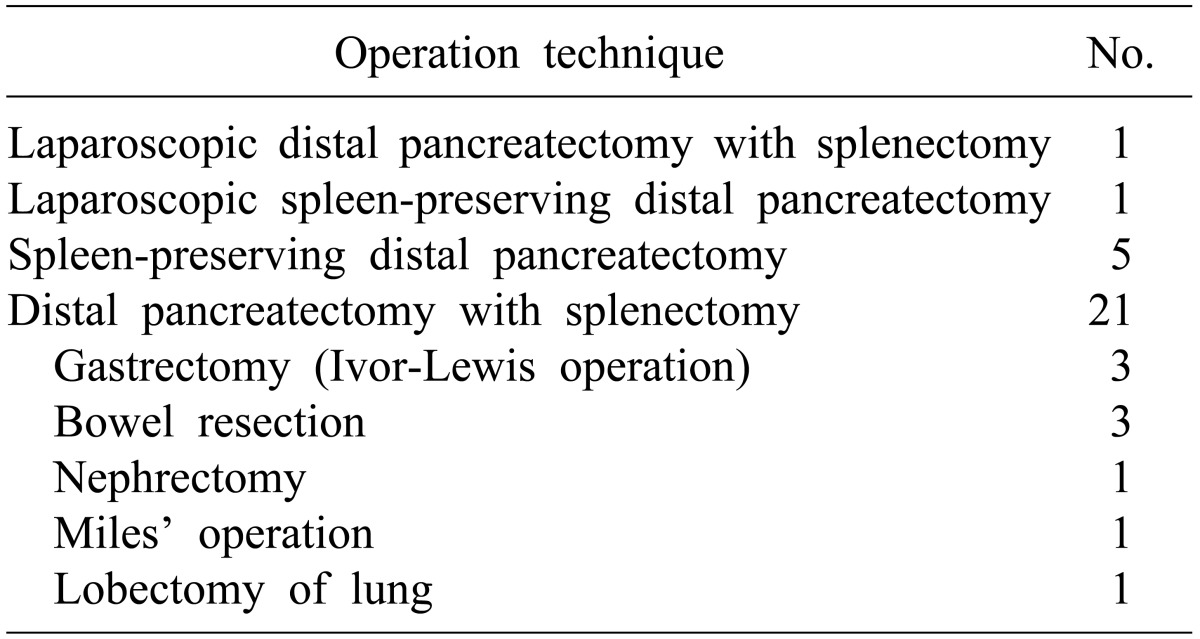

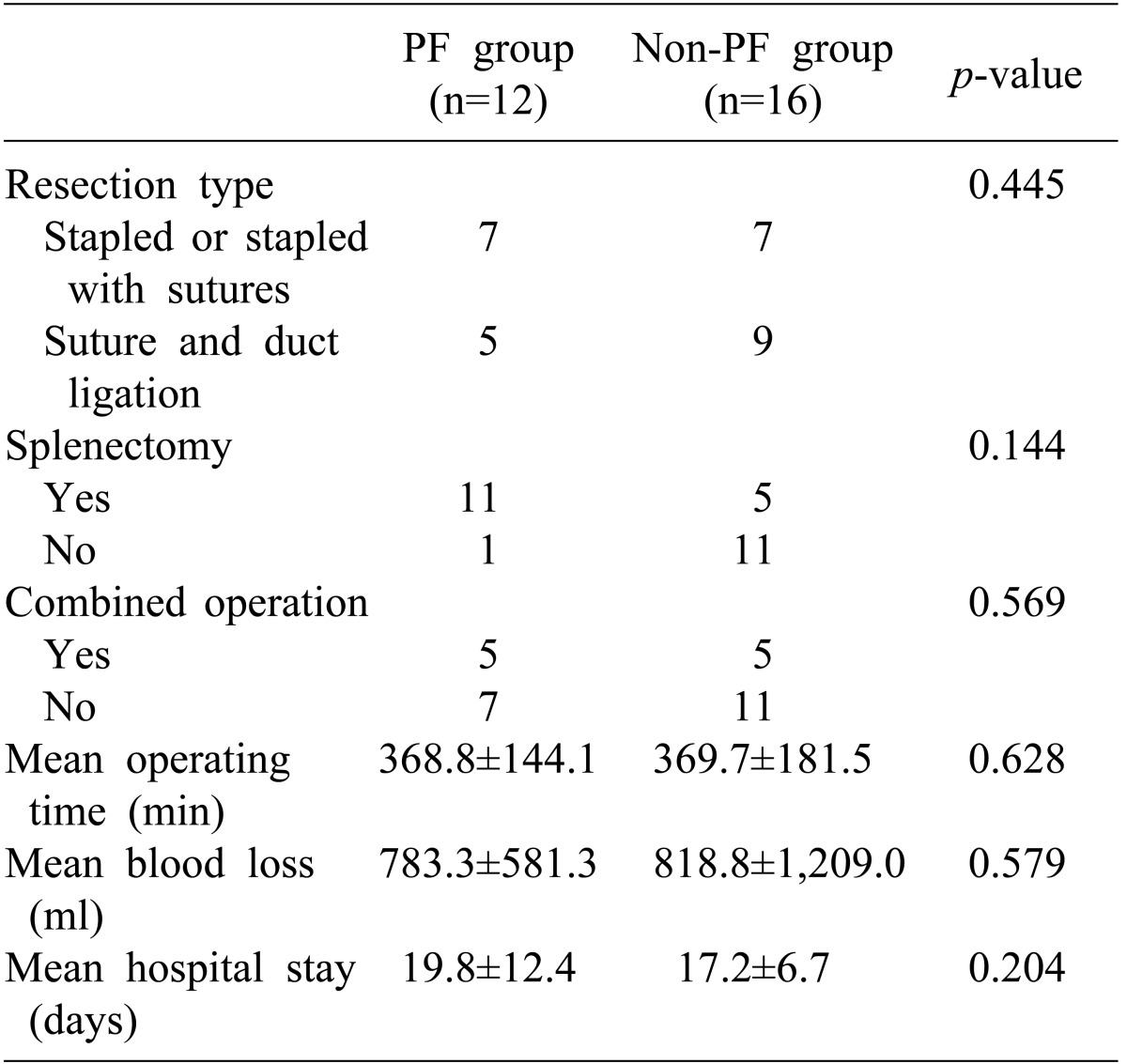

The ratio of males to females was 10 : 18, and the mean age of the pancreatic fistula group and the non-pancreatic fistula group was 49.5±13.4 and 53.9±11.9 years, respectively. There were 12 cases of malignant tumors and 16 cases of benign neoplasms (Table 1). Open and laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy was performed in 26 cases and 2 cases, respectively. Distal pancreatectomy with concurrent resection of another organ except spleen was performed in 9 cases (Table 2).

The morbidity and mortality associated with pancreatic fistulas occurred in 12 patients (42.9%) and 0 (0%), respectively. No transfusion was done during surgery. Postoperative complications except for pancreatic fistula included 1 case of wound infection and 2 cases of left-sided pleural effusion. Percutaneous thoracotomy was performed in 1 case of pleural effusion. Based on the ISGPF criteria of pancreatic fistula, 8 cases (28.6%) were classified as grade A, 3 cases (10.7%) as grade B and 1 case (3.6%) as grade C (Table 3). In 1 case of grade C pancreatic fistula, an additional percutaneous drainage procedure was performed and the drainage tube was removed when the drainage volume was less than 5 ml/day, which was the same procedure as that used in the grade B pancreatic fistula group.

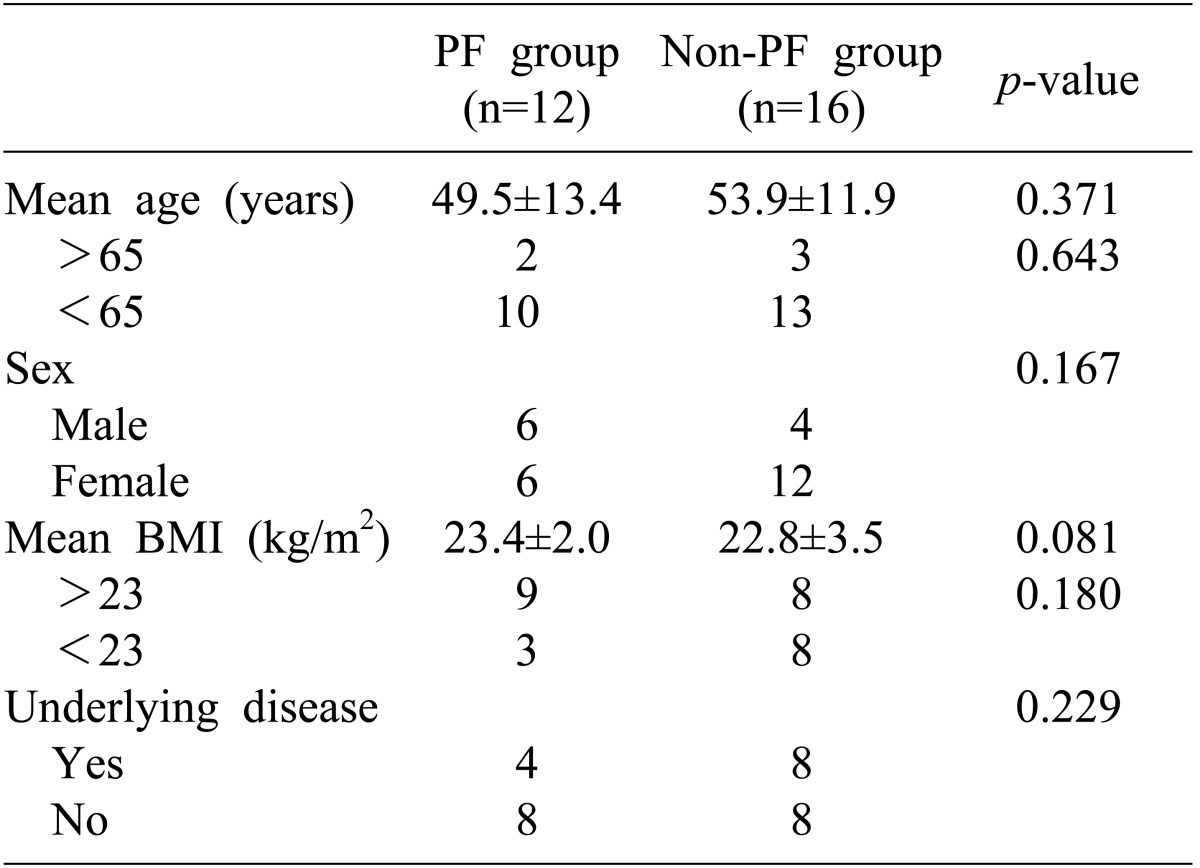

There was no significant correlation between the preoperative patient-related factors and the incidence of pancreatic fistula (Table 4) and between the preoperative surgery-related factors and the incidence of pancreatic fistula (Table 5). Although the mean body mass index (BMI) was higher in patients with pancreatic fistula than in patients without pancreatic fistula, it was not statistically significant (p=0.081, Table 4).

Go to :

Although mortality after pancreatectomy has decreased, the incidence of postoperative complications is still high.123456713 Surgeons make special efforts to reduce the incidence of pancreatic fistula, because pancreatic fistula causes many other complications, which increase the duration of hospital stays or cause a life-threatening condition.12

The definition of pancreatic fistula based on ISGPF criteria is when the measured amylase level of the drainage fluid is greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal serum amylase levels, regardless of the volume. But, the definition of pancreatic fistula is still not clear because some reports have defined pancreatic fistula on the basis of the drain output.2314 Based on the ISGPF classification, there were 8 cases (28.6%) of grade A pancreatic fistula, 3 cases (10.7%) of grade B pancreatic fistula and 1 case (3.6%) of grade C pancreatic fistula in our study. Its incidence was reduced because only 2 cases (7.2%) with the condition in which an amylase level of drainage fluid greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal serum amylase level and the drainage volume was more than 30 ml/day were added to the definition. This might be the reason that the incidence of pancreatic fistula varies significantly, because the incidence becomes lower when the drainage volume is added to the definition.2314

ISGPF recommends an abdominal CT scan only when necessary. We checked the amylase level in the drainage fluid on the 7th postoperative day and performed an abdominal CT scan at the same time. Among the 28 cases, a percutaneous drainage procedure was performed in only one case due to abnormal fluid collection on an abdominal CT scan. In this case, because the drainage tube was not located precisely in the cut surface, amylase levels in the drainage fluid were not greater than 3 times the upper limit of the normal serum amylase level. The drainage tube should be located precisely in the cut surface of the pancreas for prevention of life-threatening complications and for avoiding additional procedures. Abdominal CT scan may be useful to assess the location of the drainage tube and the diagnostic reliability of the amylase level. Therefore, abdominal CT scan would be necessary only in cases where the clinical symptoms were obvious, or where postoperative changes in the location of the drainage tube is suspected for prevention of severe complications such as pancreatic fistula.

There have been many reports regarding the causative factors of pancreatic fistula. Management of the pancreatic cut surface after pancreatectomy, concurrent resection of another organ, and operation time have been reported as the causative factors of pancreatic fistula in most cases.34815 Also the incidence of pancreatic fistula is higher when the pancreatic tissue is soft, the patient is a male or is obese (BMI>30 kg/m2), or has a poor nutritional status.89

Among the various perioperative factors in our investigation, only BMI >23 kg/m2 was related to occurrence of pancreatic fistula but did not show statistical significance. Distal pancreatectomy with concurrent resection of another organ except spleen was performed in 9 cases, and had no correlation with the occurrence of pancreatic fistula. Statistical significance could not be found between the occurrence of pancreatic fistula and prolonged operation time due to concurrent resection or duration of hospital stay.

Although various methods for the management of the remnant pancreas, - such as ligation methods for the pancreatic duct, suturing methods for the cut surface of the pancreas, use of auto-suture material, fibrin bio-adhesives, patches, meshes to reduce the occurrence of pancreatic fistula - have been developed, the prevention of pancreatic fistula is not an easy task.3413161718192021 We sutured the cut surface during pancreatectomy by using sealing material. Otherwise, ligation of the main pancreatic duct was done before placing continuous sutures. Fibrin bio-adhesive (Greenplast), and a hemostat product (Surgicell) were applied and somatostatin derivatives were used in all cases. Thus, the relationship between somatostatin derivatives and the occurrence of pancreatic fistula could not be evaluated. In two cases of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy, the operation was performed using only auto-suture material and pancreatic fistula did not occur.

There are many complications reported after distal pancreatectomy. They included pancreatic fistula, intra-abdominal abscess, anastomotic failures, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, wound infection and renal failure. 1622 Among these complications, pancreatic fistula was involved in the formation of intra-abdominal abscesses and anastomotic failures in multi-visceral resections. These complications were treated by interventional drainage and operative revision.16 In our study, there was one case of intra-abdominal abscess and no anastomotic failures in multi-visceral resections. An additional percutaneous drainage procedure was performed in the case of an intra-abdominal abscess.

Although our study included only elective surgery, the incidence of pancreatic fistula was similar to that in many other reports.123456710111213141516171819 The incidence of pancreatic fistula was still the same in that these patients were relatively healthy, although the group included patients having some co-morbidity with an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score of 1-2. On this point, it is likely that the experience of surgeons affects the postoperative complication rate.

The drainage tube should be located precisely in the cut surface of the pancreatectomy to prevent pancreatic fistula. Abdominal CT scan on the 7th postoperative day may provide information for assessing the diagnostic reliability of amylase levels in the drainage fluid.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work supported by clinical research grant from Pusan National University Hospital 2011.

Go to :

References

1. Kim HS, Jo HJ, Jeon TY, Sim MS. Factors influencing the pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Korean J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001; 5:147–154.

2. Harris LJ, Abdollahi H, Newhook T, et al. Optimal technical management of stump closure following distal pancreatectomy: a retrospective review of 215 cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010; 14:998–1005. PMID: 20306151.

3. Ferrone CR, Warshaw AL, Rattner DW, et al. Pancreatic fistula rates after 462 distal pancreatectomies: staplers do not decrease fistula rates. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008; 12:1691–1697. PMID: 18704597.

4. Yoshioka R, Saiura A, Koga R, et al. Risk factors for clinical pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy: analysis of consecutive 100 patients. World J Surg. 2010; 34:121–125. PMID: 20020297.

5. Crist DW, Sitzmann JV, Cameron JL. Improved hospital morbidity, mortality, and survival after the Whipple procedure. Ann Surg. 1987; 206:358–365. PMID: 3632096.

6. Fernández-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Standards for pancreatic resection in the 1990s. Arch Surg. 1995; 130:295–299. PMID: 7887797.

7. Aldridge MC, Williamson RC. Distal pancreatectomy with and without splenectomy. Br J Surg. 1991; 78:976–979. PMID: 1913121.

8. Kelly KJ, Greenblatt DY, Wan Y, et al. Risk stratification for distal pancreatectomy utilizing ACS-NSQIP: preoperative factors predict morbidity and mortality. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011; 15:250–259. PMID: 21161427.

9. Sledzianowski JF, Duffas JP, Muscari F, Suc B, Fourtanier F. Risk factors for mortality and intra-abdominal morbidity after distal pancreatectomy. Surgery. 2005; 137:180–185. PMID: 15674199.

10. Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula Definition. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005; 138:8–13. PMID: 16003309.

11. Pratt WB, Maithel SK, Vanounou T, Huang ZS, Callery MP, Vollmer CM Jr. Clinical and economic validation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification scheme. Ann Surg. 2007; 245:443–451. PMID: 17435552.

12. Pratt WB, Callery MP, Vollmer CM Jr. Risk prediction for development of pancreatic fistula using the ISGPF classification scheme. World J Surg. 2008; 32:419–428. PMID: 18175170.

13. Nathan H, Cameron JL, Goodwin CR, et al. Risk factors for pancreatic leak after distal pancreatectomy. Ann Surg. 2009; 250:277–281. PMID: 19638926.

14. Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, et al. Critical appraisal of 232 consecutive distal pancreatectomies with emphasis on risk factors, outcome, and management of the postoperative pancreatic fistula: a 21-year experience at a single institution. Arch Surg. 2008; 143:956–965. PMID: 18936374.

15. Zhou W, Lv R, Wang X, Mou Y, Cai X, Herr I. Stapler vs suture closure of pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy: a meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2010; 200:529–536. PMID: 20538249.

16. Seeliger H, Christians S, Angele MK, et al. Risk factors for surgical complications in distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2010; 200:311–317. PMID: 20381788.

17. Sheehan MK, Beck K, Creech S, Pickleman J, Aranha GV. Distal pancreatectomy: does the method of closure influence fistula formation? Am Surg. 2002; 68:264–267. PMID: 11893105.

18. Kajiyama Y, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, Tsutsumi K, Kinoshita Y, Akiyama H. Quick and simple distal pancreatectomy using the GIA stapler: report of 35 cases. Br J Surg. 1996; 83:1711. PMID: 9038547.

19. Takeuchi K, Tsuzuki Y, Ando T, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: is staple closure beneficial? ANZ J Surg. 2003; 73:922–925. PMID: 14616571.

20. Bilimoria MM, Cormier JN, Mun Y, Lee JE, Evans DB, Pisters PW. Pancreatic leak after left pancreatectomy is reduced following main pancreatic duct ligation. Br J Surg. 2003; 90:190–196. PMID: 12555295.

21. Nakamura Y, Uchida E, Aimoto T, Matsumoto S, Yoshida H, Tajiri T. Clinical outcome of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009; 16:35–41. PMID: 19083146.

22. Fahy BN, Frey CF, Ho HS, Beckett L, Bold RJ. Morbidity, mortality, and technical factors of distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2002; 183:237–241. PMID: 11943118.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download