This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) has been widely used, but it has a potential risk of tumor spread along the catheter tract. We herein present a case of solitary PTBD tract metastasis after curative resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Initially, endoscopic nasobiliary drainage was done on a 65 year-old female patient, but the cholangitis did not resolve. Thus a PTBD catheter was inserted into the right posterior duct. Right portal vein embolization was also performed. Curative surgery including right hepatectomy and bile duct resection was performed 16 days after PTBD. After 12 months, serum CA19-9 had increased gradually without any symptoms. Finally, a small right pleural metastasis was found through strict tumor surveillance for 6 months. Chemoradiation therapy was performed, but there was no response to treatment. As the tumor progressed, she complained of severe dyspnea and finally died from tumor dissemination to the chest and bones 18 months after the first detection of PTBD tract recurrence and 36 months after surgery. No intra-abdominal recurrence was found until the terminal stage. This PTBD tract recurrence was attributed to the PTBD even though it was in place for only 16 days. Although such recurrence is rare, its risk should be taken into account during follow-up of patients who have received PTBD before.

Go to :

Keywords: Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, Tract recurrence, Resection

INTRODUCTION

Biliary obstruction from malignancy of the hepatobiliary system requires biliary drainage through a percutaneous or endoscopic approach. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) has been widely used for a long time, but recently endoscopic biliary drainage has been preferred as a primary method because of various disadvantages of PTBD such as procedure-related complications and tumor spread along the PTBD tract.

123 Endoscopic nasobiliary biliary drainage (ENBD) or endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage is effective for biliary decompression of the distal cholangiocarcinoma. Thus PTBD is only occasionally necessary. However, in perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, endoscopic biliary drainage is often not feasible or effective due to complexity of the biliary obstruction patterns. Thus, PTBD is still frequently performed for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, with concomitant use of ENBD. Although the Nagoya University group reported a 5.6% incidence of PTBD tract recurrence after resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma,

1 the actual incidence of PTBD tract recurrence does not appear to be so high. We herein present a unique case of solitary catheter tract metastasis associated with PTBD after resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Go to :

CASE

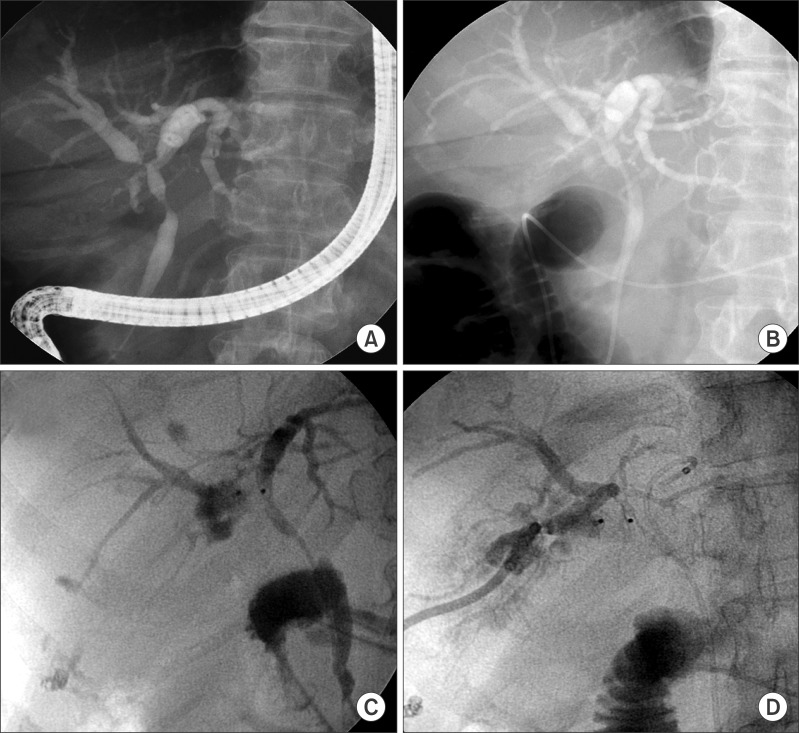

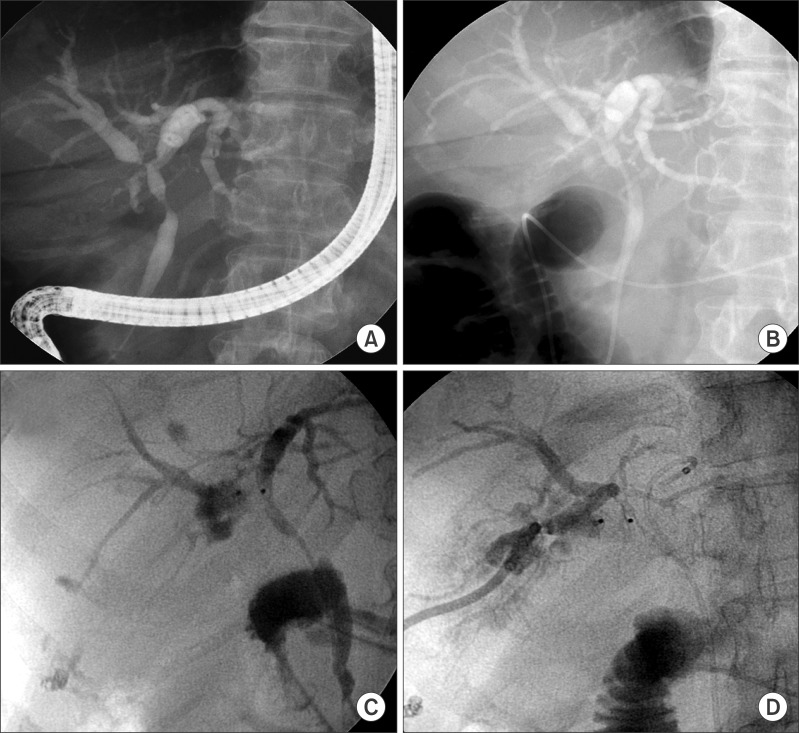

The patient was a 65 year-old female who gave us the impression that she had perihilar cholangiocarcinoma and a sudden onset of obstructive jaundice. Initial endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) showed multifocal narrowing of the common hepatic duct and right intrahepatic duct (

Fig. 1), suggesting a diagnosis of Klatskin tumor of the Bismuth-Corlette type IIIa. Endoscopic biopsy showed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, but bile cytology was not negative for malignant cells. After 10 days' biliary decompression with ENBD, the serum total bilirubin decreased from 9.0 mg/dl to 2.1 mg/dl, but intermittent fever with cholangitis did not resolve. A PTBD catheter was inserted into the right posterior duct (

Fig. 1) to treat the segmental cholangitis. Subsequently, right portal vein embolization was performed to facilitate ipsilateral hepatic atrophy and contralateral future remnant liver hypertrophy.

456 Two weeks' waiting after right portal vein embolization changed the left liver proportion to the total liver volume from 37% to 48%.

| Fig. 1Preoperative cholangiography showing hilar bile duct obstruction. (A and B) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography was performed for diagnosis and biliary decompression. (C and D) Since the endoscopic nasobiliary biliary drainage was not sufficient for biliary decompression of the right lobe, a percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage catheter was inserted.

|

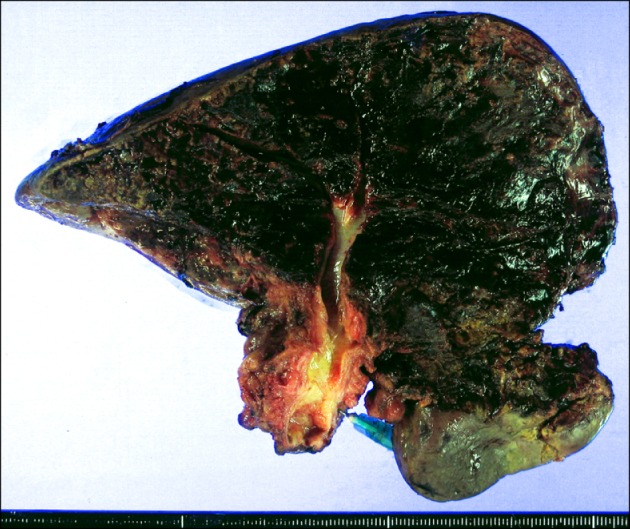

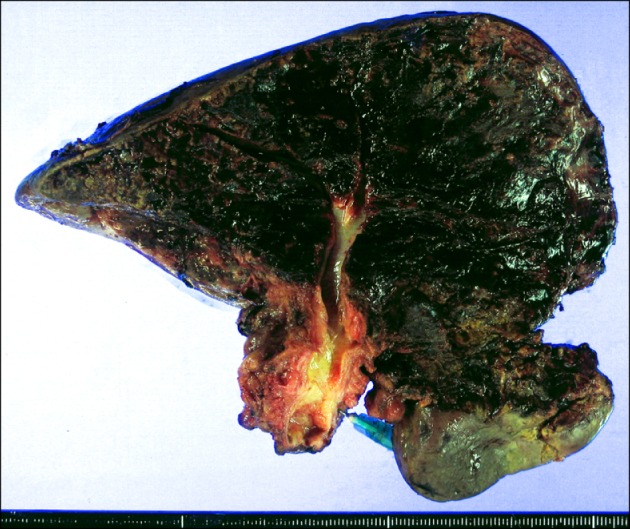

Right hepatectomy with resection of some of segment IVa and the whole caudate lobe, bile duct resection, lymph node dissection, and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy for two remnant liver duct openings were performed 16 days after PTBD. The pathologic report showed that the bile duct tumor was a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of 4 cm in greatest dimension, involving the right intra- and extrahepatic bile duct and common hepatic duct with extension to the perimuscular soft tissue, but no involvement of hepatic parenchyma (

Fig. 2). Both left hepatic duct and distal duct resection margins were tumor-negative. There was perineural invasion, but no lymphovascular invasion. All four lymph nodes were tumor-negative. She recovered uneventfully and discharged 2 weeks after surgery.

| Fig. 2Gross photograph of the resected right liver specimen.

|

Although the resection was classified as an R0 resection, adjuvant chemoradiation therapy with Capecitabine and external beam radiation was administered for 6 weeks.

She underwent routine follow-up studies every 2-3 months for cancer surveillance.

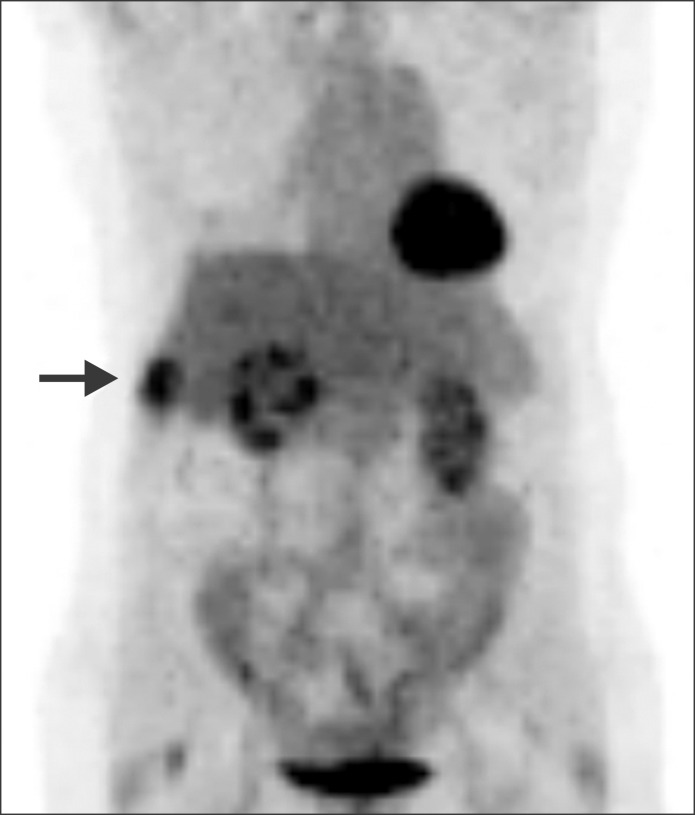

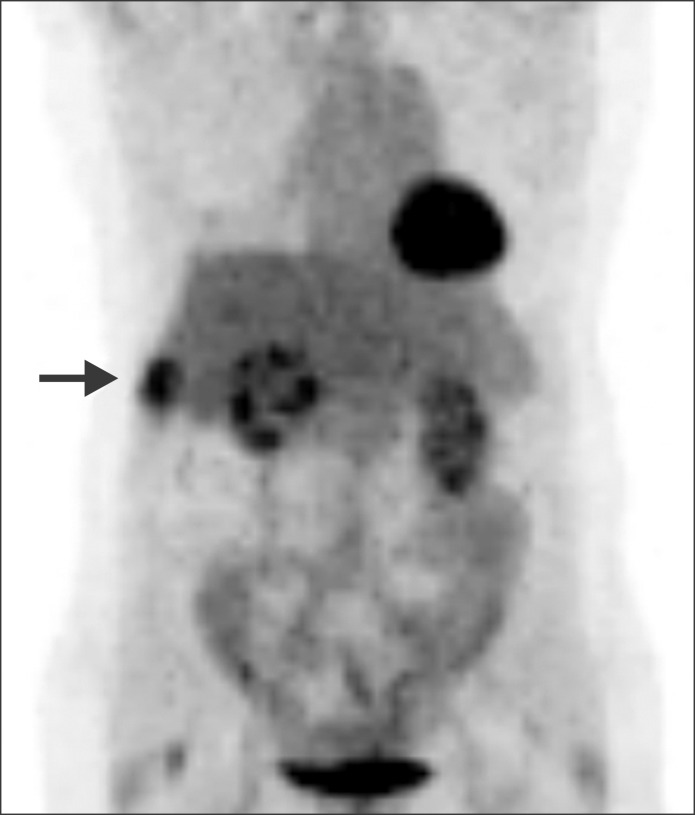

5 By 12 months, the serum CA19-9 had increased gradually, but dynamic computed tomography (CT) and fusion whole body [

18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (

18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) did not show any abnormality suggesting tumor recurrence. Since the serum CA19-9 continuously increased to over 200 U/ml, imaging studies were repeated every month. On PET scanning performed at 18 months postoperatively, evidence of recurrence was identified, showing increased metabolic activity of the right lateral chest wall (

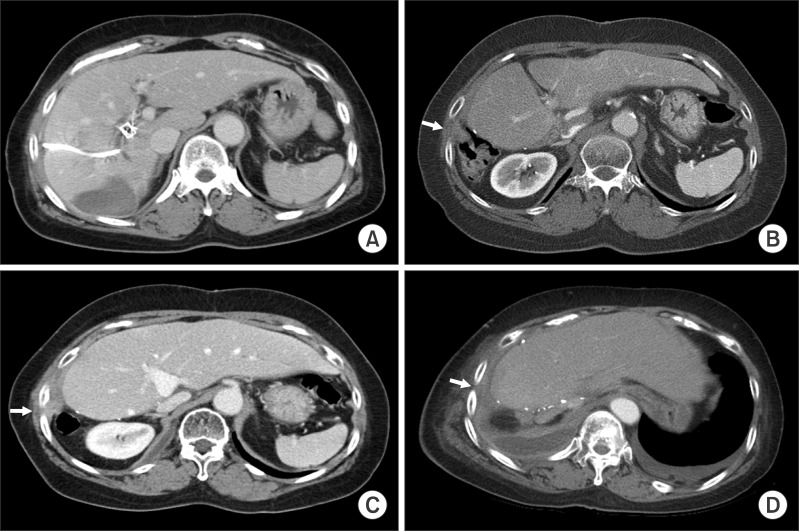

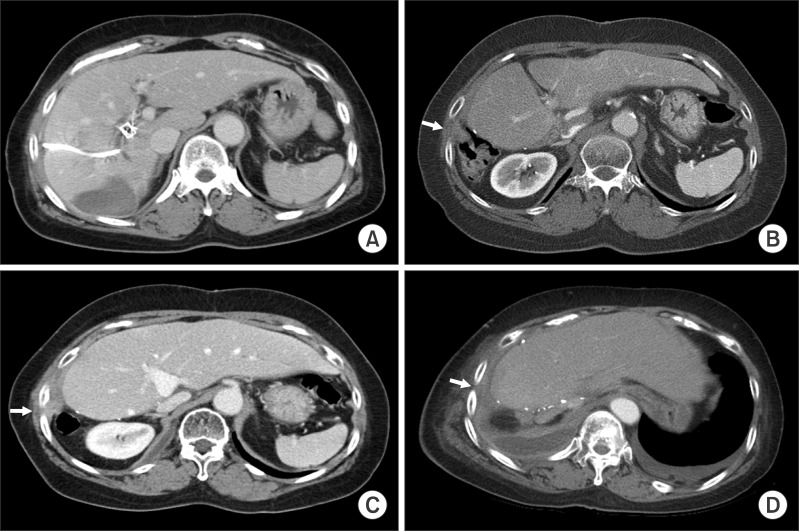

Fig. 3). Chest CT showed a small subpleural nodule in the right chest, implicating a benign nodule such as inflammatory granuloma. However, after matching with PET findings, this subpleural nodule was highly suspected of PTBD tract metastasis. At this time, she was completely free of any symptom (

Fig. 4).

| Fig. 3An image of whole body positron emission tomography taken 18 months postoperatively showed increased metabolic activity of the right lateral chest wall (arrow).

|

| Fig. 4Computed tomography images of the sequences of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) tract recurrence. (A) A PTBD catheter was inserted before surgery; (B) A granuloma-like nodule was detected at the right chest wall, which was highly suspected of being a metastasis after matching it with findings of positron emission tomography at postoperative month 18; (C) Overt PTBD tract metastasis was identified at the right chest at postoperative month 24; (D) There was no evidence of intra-abdominal metastasis 4 months before the patient's death due to tumor dissemination. Arrows indicate the site of PTBD tract recurrence.

|

Worrying about the subsequent occurrence of another intra-abdominal recurrence, we decided to perform palliative chemoradiation therapy instead of radical resection of the involved chest wall. Even after the second chemoradiation therapy, serum CA19-9 had gradually increased, implying that there was no treatment response.

Three months after a second regimen of chemoradiation therapy, right pleural effusion developed; it was drained through a pigtail. A pleural fluid smear showed negative findings for malignant cells. As time passed, there were gradual increases in the extent of soft tissue mass and infiltration in the right lateral chest wall, and the sclerotic changes in the right 9 th rib became more evident. Finally, metastatic adenocarcinoma cells were found at the pleural effusion smear.

Fiver months after the second chemoradiation therapy, a third round of radiation therapy was done to control bone pain at the thoracic vertebra metastasis. As the tumor progressed, she complained of severe dyspnea. She finally died from tumor dissemination to the chest and bones 18 months after first detection of PTBD tract tumor recurrence and 36 months after surgery. Unexpectedly, even at the terminal stage, there was no evidence of intra-abdominal recurrence on follow-up CT scans.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

PTBD tract tumor recurrence after resection of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma is uncommon, but the reported incidence from the Nagoya University group was much higher than expected.

1 In fact, it is not possible to estimate its actual incidence because their report is only one collective review from a large-volume center and others have presented sporadic cases so far.

178910111213141516 According to our institutional experience,

45 its incidence is around 2%.

However, after looking into the details of the Nagoya University experience, we found that it included several non-negligible risk points specific to that institution, including presence of synchronous metastasis at the time of surgery, high incidence of multiple PTBD catheters and prolonged stay of PTBD catheters.

1 They reported that the independent risk factors for PTBD tract recurrence were multiple catheters, duration of PTBD over 60 days and papillary tumor growth. Considering that recently a single PTBD with or without ENBD for a few weeks has often been used for biliary decompression for patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, the actual risk of tumor metastasis associated with PTBD may be lower than previously reported.

The present case appears to be very unusual because of the absence of intra-abdominal recurrence. In fact, most PTBD tract recurrences were followed by subsequent intra-abdominal recurrence, inducing multiple tumor recurrences that led to shortened survival. Therefore, locoregional control of PTBD tract recurrence would not be effective for recurrence control. Unlike other usual patients with PTBD tract recurrence, this patient did not show any intra-abdominal recurrence until the tumor dissemination leading to her death. Thus, extra-abdominal metastasis initiated from solitary PTBD site recurrence led to the patient's death. Regrettably, if the PTBD had been avoided, this patient would have been free from such fatal metastasis.

Recently, endoscopic biliary drainage has become the primary choice for biliary decompression in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma.

2 If endoscopic biliary drainage is not successful for effective drainage, PTBD may be used as like in this patient with complex biliary obstruction patterns. Because the incidence of solitary recurrence which may be benefited from not performing PTBD is very uncommon as far as we know, the actual risk and benefit of PTBD should be validated again with large-volume studies other than the Nagoya University experience. Until now, although endoscopic biliary drainage would be performed first, there is no absolute reason to hesitate to perform PTBD when it is indicated because its actual risk of PTBD tract is not completely verified.

To minimize the risk of PTBD tract recurrence, intraoperative en bloc resection of the entry sites at the liver capsule and abdomen-chest wall is suggested.

1 If the PTBD catheter is inserted at the resected liver side, nearly all of the intrahepatic tract portions are removed. It is feasible to concurrently resect some of the anterior abdominal wall around the left-sided catheter insertion site. In contrast, it is difficult to remove the chest wall or right flank near the right-sided catheter insertion site. Thus, we have applied cauterization injury to the PTBD tract with an argon beam coagulator on occasion. On the other hand, if the PTBD catheter is inserted in the remnant liver side, many of the intrahepatic tract portions would be left. It is also feasible to concurrently resect some of the anterior abdominal wall and liver around the left-sided catheter insertion site. We occasionally inject alcohol around the catheter insertion site at the left liver instead of doing a local excision. For right-sided PTBD, a small local excision or burning coagulation can be applied to the flank and liver side.

In conclusion, we present a case of unique solitary tumor recurrence at the PTBD tract, in which the PTBD catheter was kept for only 16 days. Although such a recurrence is rare, its risk should be taken into account during follow-up of patients who had received PTBD before.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download