Abstract

Purpose

This study was aimed to investigate the impact of job stress on low back symptoms among Clinical nurses (CNs) in university hospital.

Methods

A total of 322 CNs employed in a hospital in Seoul were interviewed by a well-trained interviewer using the structured questionnaire. Data collected for this study includes demographics, social and work characteristics, low back symptoms, and job stress. To test the impact of job stress on low back symptoms, we used multiple logistic regression analysis.

Results

The prevalence of low back symptoms was 25.8% in this study. Low back symptoms differed significantly by factors, such as physical work burden, past history of injury and work duration. Also low back symptoms differed significantly by organizational system among independent variables of job stress. In a multiple logistic regression analysis, the odds ratio of organizational system to low back symptoms was 2.07 after an adjustment.

Nursing occurs in an environment that is notable for its high physical strain on the lower back area. This is due to the fact CNs usually work in a standing position. Among female workers, nursing aides, licensed or practical nurses and maids had the highest rates of back pain (Heibert, Weiser, Campello, & Nordin, 2007). Recent report emphasized that complaints of initial back pain can be the appropriate time to identify individuals who are at a higher risk for developing chronic or acute musculoskeletal symptoms (Daraiseh, Cronin, Davis, Shell, & Karwowski, 2009).

Along with a demanding physical workload, hospital nurses felt job stress through other environmental factors that include job demand, insufficient job control, interpersonal conflict, organizational system, occupational climate etc. They also felt job stress from the rapid change of information, various health care needs, expanded work expectation, and advance nursing practice (Kim, Park, & Park, 2009). All of these factors can have a mentally and physically negative impact on nurses (Kim et al., 2006). Occupational errors or accidents involving CNs have a direct and critical influence on the life and prognosis of patients and these are other important issues that must be addressed (Suzuki et al., 2004).

Work-related musculoskeletal symptoms are disorders of the nerves, tendons, muscles, and supporting tissues that result from, or are made worse by, stressful working conditions (Cohen, Gjessing, Fine, Bernard, & McGlothlin, 1997) and are the single target category for work-related health problems in most Asian countries including Korea (Lee, Kim, & Kim, 2008). The development of musculoskeletal symptoms is caused by the accumulation of micro injuries from repetitive motion or physical stress. Numerous studies have shown that musculoskeletal symptoms are attributed to multiple factors, such as physical workload and psychosocial factors at work (Boswell, & McCunney, 2003; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009; Cathilic university, 2003; Halpern, 2007; Ministry of employment and labor, 2004; Rempel, & Janowitz, 2007).

Korea has seen a marked increase in musculoskeletal symptoms since the 1990s due to the increased use of computer terminals, repetitive work, increased work stress, and aging in the working population (Lee, Han, Ahn, Hwang, Kim, 2007; Ministry of Labor, 2010). In Korea, the musculoskeletal symptoms of nonfatal occupational illness have accounted for 68%, 74%, and 77% for the years of 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively (Park, Kim, & Seo, 2008). These studies have focused on the 6 areas of musculoskeletal symptoms, and not specifically low back symptoms.

Until now, epidemiologic researches on musculoskeletal injuries or disorders (Kim et al., 2005; Nam & Lee, 2003) have mainly been in relation to physical capacity (e.g., muscle strength, range of movement), whereas little attention has been given to low back symptoms and its psychosocial factors.

It is important to mention that working women continue to fulfill household tasks when they come back home from work. They continue to carry out their tasks at a standing position. Keeping this in mind, the primary aim of this study was to investigate the impact of job stress on low back symptoms among women CNs employed in one university affiliated hospital in Seoul. The second aim was to predict the impact factors on low back symptoms. The study was expected to provide some important basic information for establishing preventive strategies for low back symptoms among women CNs in a university hospital.

This study was conducted at one university hospital in Seoul, South Korea. A total of 500 CNs were identified as the study population. From this pool, a total of 346 women CNs were recruited for this study. After official approval from the department of nursing administration, the self-administered questionnaire was distributed to the subjects. The response rate was 69.2%. We excluded questionnaires that contained grossly incomplete data (n=24) and were able to analyze data from 322 eligible subjects. We did post hoc power analysis and got an effect size of 0.707, greater than large size with alpha=.05, sample size=322, and two tails by G Power 3.1 (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009).

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire from February to April 2007. All subjects were given a verbal explanation of the study procedures before they submitted a written informed consent. For this study, 322 eligible subjects were included in the analysis.

The questionnaire included items on socio-demographics, personal medical history, smoking, alcohol drinking habits and work related factors.

Low back symptomswere measured by using part of the KOSHA Code H-30-2003 that has been developed by the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency (KOSHA). It consisted of work-related symptoms in any of the six body regions (neck, shoulders, arms, hands/wrists, lower back, and legs/feet). For the purpose of this study, we used items that only focused on the lower back. Symptom cases were defined as having occurred at least once a month or having lasted at least one week in the past year with at least moderate pain on the pain intensity scale.

Job stress was evaluated by 24 items of the short form of the Korean Occupational Stress Scales (KOSSSF) in the work setting (Chang et al., 2005). Items were scored using the Likert scales for the response, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (always). This stress scale had seven subscales as follows: job demand (4-items), insufficient job control (4-items), interpersonal conflict (3-items), job insecurity (2-items), organizational system (4-items), lack of reward (3-items), and occupational climate (4-items). The levels on the subscales of occupational stress were divided by using a median as the high and low group.

Descriptive statistics were used to examine the distribution of demographics, social, and occupational characteristics. χ2-test was used to estimate the difference in the existence of low back symptoms according to 4 categorical analyses: 1. demographics, 2. social, 3. work characteristics, and 4. job stress. Multiple logistic regression modeling was used to examine the impact of job stress on low back symptoms. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS/WIN 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All P values were based on two-sided tests and were considered to be statistically significant (p<.05).

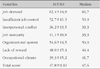

The prevalence of low back symptoms was 25.8% in the study subjects. About 52% were between 20 and 29 years of age, 33% were between 30 and 39 years of age, and 15% were older than 40 years, indicating that the majority of the subjects were in their 20s and 30s. There was no difference in the prevalence of low back symptoms according to age and marital status. However, a significant difference in the prevalence of low back symptoms was observed in having physical work burden (χ2=18.2, p<.001). There was a difference in the prevalence of low back symptoms from having a past history of injury, although a borderline statistical significance was observed (χ2=3.64, p=.056). Significant difference was shown in work duration, indicating that the majority of prevalent cases occurred less than 10 years (63.7%) (χ2=11.1, p=.025) (Table 1).

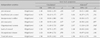

The average score of total job stress was 47.8±9.1. In the mean scores for individual subscales, job demand was the highest. The second highest was organizational system and the third highest was insufficient job control (Table 2).

The prevalence of low back symptoms differed significantly in organizational system, indicating that the prevalence of was significantly higher in the high stress group of organizational system than in the low stress group (χ2=4.36, p=.037). However, occupational climate had a borderline statistical significance (χ2=3.60, p=.058) (Table 3).

Physical work burden, past history of injury, and work duration had an impact on low back pain symptoms. Physical work burden and past history of injury had significant effects on low back symptoms after controlling for age, marital status, housework, and work department (Odd's ratio 3.31, p<.001; Odd's ratio 1.71, p=.044, respectively). Subjects who had worked for a period of 5~9 years had a 3.81 times greater possibility of experiencing low back symptoms than those who worked for less than 1 year (p=.039) (Table 4).

To determine the association between job stress and low back symptoms, a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed on the study subjects. Organizational system was a significant factor for low back symptoms. The highest stress group in organizational system had 2.07 times greater possibility of experiencing low back symptoms than the low stress group (95% CI 1.03~4.19). The odds ratio of occupational climate to low back symptoms was 1.63 (95% CI 0.98~2.72 and was not significant after an adjustment (Table 5).

We investigated factors, including socio-demographic variables and job stress that were related to low back symptoms among women CNs employed in one university hospital. The prevalence of low back symptoms was 25.8%. Compared to other study results on Korean employees from Chang et al. (2004), our study indicated slightly higher findings (24.9% vs 25.8%). The average score of total job stress was 47.8 (SD=9.1) in this study and our findings were consistent with a previous study on hospital nurses (Kim, Kim, & Ahn, 2007).

This study revealed that job demand was the highest category of job stress in the subgroup analysis. This result was consistent with previous studies (Kim et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009). The mean score of job demand was 62.4 in this study. In comparison to 58.8 in a previous report (Chang et al., 2004), these findings indicated that nurses had high work stress due to high workload and job demand in hospital settings.

We found that physical work burden, past history of injury and work duration had significant effects on low back symptoms. Since hospital nursing takes place in a work environment that is notable for its high use of the lower back in physical activities, such as moving patients, nursing couch, and working in a standing position for long hours (Kim et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009), the prevalence of low back symptoms has been reported to be higher in nurses than in the general population (Heibert et al., 2007). In this study, organizational system had a significant impact on low back symptoms and it needs to be compared by job classification in the future. We found that the highest level of job stress was observed in job demand and the second highest level in organizational system, indicating that work characteristics of hospital nursing could be relatively unpredictable and produce feelings of insufficient job control. These findings were consistent with previous reports from Korean nurses (Kim et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009). It is possible that the current work environment could make high work stress in hospital settings and increase psychological strain, leading to an increased prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms (Hurrell & Kelloway, 2007). As there are various job types in hospital settings, hospital nurses should provide many kinds of health services in cooperation with other hospital staffs, such as hospital officials and paramedical staffs.

One limitation of this study is the cross-sectional design, because we could not observe a cause-and effect relationship between low back symptoms and job stress over an extended period of time. Another limitation is the use of a measurement tool that relies on subjective reporting. Finally, other potential confounding variables were not evaluated. Therefore, a more comprehensive study evaluating low back symptoms both at the workplace and in daily life need to be carried out in the future. Notwithstanding the known limitations, we thought that the subjective responses of the subjects were somewhat essential for the purpose of investigating our interest variables as those variables such as low back symptoms and work stress contain subjective characters in and of itself. Moreover, diagnosis of low back musculoskeletal disorders and work stress may often be controversial due to a lack of standardized diagnostic criteria on which the study of its prevalence is dependent upon.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that low back symptoms were associated with job stress related to organizational system for hospital nurses. To prevent low back musculoskeletal symptoms in hospital nurses, it is important to consider not only job contents but also work environment related to the job stress. Further investigation will be needed to establish preventive strategies for hospital nurses.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Boswell R.T., McCunney R.J. McCunney R.J, editor. Musculoskeletal disorders. A practical approach to occupational and environmental medicine. 2003. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;314–331.

2. Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work, 2009. United States Department of Labor 2009. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (BLS). 2009. Retrieved Nov 9, 2010. from: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh2/pdf.

3. Catholic University. Occupational health. 2003. Seoul: Soomoonsa;415–441.

4. Chang S., Kang D., Kang M., Koh S., Kim S., Kim S., et al. Standardization of job stress measurement scale for Korean employees. The 2nd year project. 2004. Incheon: Occupational Safety & Health Research Institute;69–74.

5. Chang S.J., Koh S., Kang D., Kim S., Kang M., Lee C., et al. Developing an occupational stress scale for Korean employees. Korean Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2005. 17(4):297–317.

6. Cohen A.L., Gjessing C.C., Fine L.J., Bernard B.P., McGlothlin J.D. Elements of ergonomics programs: A primer based on workplace evaluations of musculoskeletal disorders. 1997. Cincinnati (OH): National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health;3–4.

7. Daraiseh N.M., Cronin S.N., Davis L.S., Shell R.L., Karwowski W. Low back symptoms among hospital nurses, associations to individual factors and pain in multiple body regions. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2009. 40(1):19–24.

8. Faul F., Erdfelder E., Buchner A., Lang A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009. 41:1149–1160.

9. Halpern M. Rom W.N, editor. Ergonomics and occupational biomechanics. Environmental and occupational biomechanics. 2007. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;905–923.

10. Heibert R., Weiser S., Campello M., Nordin M. Rom W.N, editor. Nonspecific low back pain. Environmental and occupational biomechanics. 2007. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;925–936.

11. Hurrell J., Kelloway E. Rom W.N, editor. Psycohological job stress. Environmental and occupational biomechanics. 2007. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;855–866.

12. Kim H.C., Kim Y., Lee Y., Shin J., Lee J., Leem J., et al. The relationship between job stress and needlestick injury among nurses at a university hospital. Korean Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2005. 17(3):216–224.

13. Kim H.C., Kwon K., Koh D., Leem J., Park S., Shin J., et al. The relationship between job stress and psychosocial stress among nurses at a university hospital. Korean Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006. 18(1):25–34.

14. Kim Y.H., Kim Y., Ahn Y. Low back pain and job stress in hospital nurses. Journal of Muscle and Joint Health. 2007. 14(1):5–12.

15. Kim Y.S., Park J., Park S. Relationship between job stress and work-related musculoskeletal symptoms among hospital nurses. Journal of Muscle and Joint Health. 2009. 16(1):13–25.

16. Lee K.J., Han S., Ahn Y., Hwang J., Kim J. Related factors on musculoskeletal symptoms in selected Korean female office and blue-collar workers. Journal of Korean Society of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 2007. 17(4):289–299.

17. Lee S.W., Kim K., Kim T. The status and characteristics of industrial accidents for migrant workers in Korea compared with native workers. Korean Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2008. 20:351–361.

18. Ministry of Employment and Labor. Musculoskeletal disorders handbook. 2004.

19. Ministry of Labor. Statistics of industrial accidents and occupational diseases. 2001-2009. 2010. Ministry of Labor;10–14.

20. Nam M.H., Lee S. Effect of job stress and coping strategy on job satisfaction in a hospital works. Korean Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003. 15(1):1–11.

21. Park J.K., Kim D., Seo K. Musculoskeletal disorder symptom features and control strategies in hospital workers. Journal of the Ergonomics Society of Korea. 2008. 27:81–92.

22. Rempel D.M., Janowitz I.L. LaDou J, editor. Ergonomics & the prevention of occupational injuries. Current occupational & environmental medicine. 2007. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill;151–174.

23. Suzuki K., Ohida T., Kaneita Y., Yokoyama E., Miyake T., Harano S., et al. Mental health status, shift work, and occupational accidents among hospital nurses in Japan. Journal of Occupational Health. 2004. 46:448–454.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download