Abstract

Osteosarcoma most commonly metastasizes to the lung or the skeleton, and metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast is very rare, with only a few cases reported. Due to its rarity, little has been reported about its imaging features. In this report, we represent a 58-year-old woman with metastatic osteosarcoma to the right breast from a tibial osteosarcoma. The imaging features of the metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast by using dedicated breast imaging modalities are described. Although rare, metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast should be considered when dense calcified masses with suspicious features are seen on breast imaging in patients with a history of osteosarcoma.

Breast metastases from extramammary malignancies are uncommon, as most metastatic breast tumors are from the contralateral breast [12]. Extrapulmonary metastases from primary osteosarcomas are also uncommon, with metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast being extremely rare. Although several cases of metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast have been reported in the literature [34,5,6], none of them have exhibited the imaging features of this rare form of metastasis. Herein, we report a case of metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast, focusing on imaging features seen using dedicated breast imaging modalities.

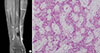

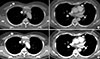

A 58-year-old Korean woman was referred to our institution for a mass in the right distal tibia detected with magnetic resonance imaging performed at an outside clinic (Figure 1A). The patient had been suffering from pain in her right ankle for a week. An open biopsy was performed, and the tumor was pathologically diagnosed as an osteoblastic conventional osteosarcoma (Figure 1B). She was transferred to our institution, where she subsequently underwent chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) for routine baseline evaluation. Although there was no evidence of pulmonary metastasis, two calcified nodules were discovered, one in the right breast and the other in the anterior mediastinum (Figure 2A). Based on imaging features, benign granuloma and metastasis were considered in the differential diagnosis, and short-term follow-up was recommended because the patient was scheduled for neoadjuvant intra-arterial chemotherapy. Chest CT performed three weeks later revealed size increases of the calcified masses (Figure 2B), raising the suspicion for metastasis. Therefore, the patient was referred to the breast radiologist for biopsy.

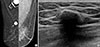

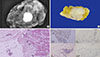

Diagnostic mammography (Figure 3A) showed a dense calcified mass in the right upper breast, with spiculated margins. Breast ultrasonography (US) of the right upper breast (Figure 3B) revealed a 1.5 cm dense calcified mass with posterior shadowing. Owing to the dense calcifications seen in the mass, percutaneous US-guided core needle biopsy was considered difficult to perform, and excisional biopsy was recommended to make a pathologic diagnosis. After the third cycle of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, excisional biopsies of the breast and mediastinal masses were performed. Specimen mammography (Figure 4A) of the excised breast mass showed the dense calcified mass within the specimen, confirming complete excision of the mass. Pathologic examination revealed a high-grade spindle cell tumor with osteoid matrix production (Figure 4B, C). Immunohistochemical staining revealed positivity for cluster of differentiation 99 (CD99) and negativity for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and basal cytokeratins (CK5/6), which further suggested metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast (Figure 4D). The mediastinal mass was also excised via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, confirming metasta-tic osteosarcoma. Currently, the patient is being treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, with no clinical or radiological findings of recurrence after 2 months of follow-up.

Osteosarcoma is the most frequent skeletal malignancy and commonly involves the long bones of the extremities. Osteosarcoma most commonly metastasizes to the lung, followed by the skeleton, pleura, and heart [7]. In contrast, breast and soft tissues are extremely rare sites for metastatic osteosarcoma. The prognoses of metastatic patients remain poor even though the outcomes of patients with localized osteosarcoma have markedly improved due to the introduction of multiorgan chemotherapy. Extrapulmonary metastasis at initial diagnosis was an independent predictive factor of poor overall survival in a recent study [8].

Incidences of breast metastases from extra-mammary malignancies are reportedly very low. Most cases are incidentally found on CT during staging rather than on dedicated breast imaging (Table 1) [9]. The breast metastasis in our case was also initially detected by chest CT, as in another case recently reported by Chan et al. [5], in which the metastatic osteosarcoma appeared as multiple discrete, round nodules with dense calcification. In a case reported by Roebuck et al. [6], metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast was also seen by chest CT as a noncalcified, soft-tissue nodule in the right subareolar region. Another report included metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast detected on bone scan images, in which they exhibited intense tracer uptake at the chest wall outside the skeletal confinements. This was later proven to be a metastatic osteosarcoma [3]. Although a couple of case reports have presented mammographic features of primary breast osteosarcoma [1011], to the best of our knowledge, no studies have reported the mammographic findings of metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast.

In our case, the spiculated margins of the metastatic mass were well delineated on mammography, which strongly suggests malignant processes, including metastasis, rather than benign dense calcifications. On the other hand, US features of the lesion appeared relatively benign, as it was a well-circumscribed mass with dense calcifications. Mammography is more sensitive and accurate in evaluating breast calcifications, and as in our case, mammography may be more useful in differentiating between primary malignancies or metastases containing calcifications and benign calcified masses, such as involuting fibroadenomas. Additionally, as in our case, immunohistochemical staining helps to differentiate metastatic os-teosarcoma from other malignant breast lesions, such as metaplastic carcinoma with osteosarcomatous differentiation. CD99 is a commonly expressed osteosarcoma antigen [12], while ER and PR are well-known breast cancer biomarkers. Basal cell type cytokeratins, including CK5/6, are widely used for detecting myoepithelial differentiation, which is observed in sarcomatoid metaplastic carcinoma [13].

As there are no specific management guidelines for this extremely rare condition, metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast has been treated similarly to other metastatic masses. The general treatment strategy for osteosarcoma consists of local control by complete surgical excision and systemic chemotherapy. Complete surgical resection of all suspected metastatic lesions reportedly has survival benefits, and this is the only chance of a cure [14]. Both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy are generally administrated before and after the surgery [14], but as of yet, there is no universal consensus on treatment of metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast [15].

In conclusion, although its incidence is very low, metastatic osteosarcoma should be considered when a dense calcified breast mass is found in a patient with a history of osteosarcoma. Dedicated breast imaging, such as mammography, is capable of providing clues to differentiate between metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast and benign calcified breast masses.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Magnetic resonance imaging and pathologic features of the osteosarcoma involving the right tibia. (A) A 4.8-cm-sized osteosclerotic mass (arrows) with periosteal reaction is seen in the diaphysis of the right distal tibia. (B) This mass was diagnosed as conventional osteosarcoma, osteoblastic type, showing lacy architectural pattern on excisional biopsy (H&E stain, ×200). |

| Figure 2Metastatic osteosarcoma detected on chest computed tomography (CT). (A) Two calcified masses were seen on initial chest CT, one in the right breast, and one at the anterior mediastinum (arrows). (B) Follow-up chest CT performed 3 weeks later revealed size increase of these masses, breast mass from 11 to 14 mm and mediastinal mass from 12 to 15 mm (arrows), raising the suspicion for metastasis. |

| Figure 3Mammography and breast ultrasonography (US) examinations of the right breast mass. (A) Mediolateral oblique views of mammography show a dense calcified mass (arrow) with spiculated margins in the right upper breast. (B) Breast US performed on the same day shows a 1.5-cm dense calcified mass with posterior shadowing. Percutaneous biopsy was considered difficult due to the dense calcifications, and the patient underwent excisional biopsy. |

| Figure 4Specimen mammography and the pathology features of the right breast mass. (A) Specimen mammography reveals the dense calcified mass (arrows) seen on mammography in the right breast, confirming complete excision of the mass. (B) Similar features are seen on gross specimen, which reveals a dense calcified mass within the breast tissue. (C) Microscopic examination shows a mass with predominant osteoid matrix production (arrows) (H&E stain, ×40). (D) Immunohistochemically, these tumor cells were positive for cluster of differentiation 99 (CD99), negative for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and cytokeratin 5/6 (CK5/6). These findings are consistent with those of metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast, rather than primary metaplastic carcinoma of the breast (×100). |

Table 1

Cases published in literature on metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast

| Year | Author | Age (yr)* | Primary site | Metastatic site | Imaging modality and findings | Pathologic type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Roebuck et al. [6] | 15 | Tibia | Breast, lung, femur | Breast US | Poorly differentiated sarcoma with myxoid differentiation |

| Lobulated hypoechoic solid mass | ||||||

| Chest CT | ||||||

| Soft-tissue nodule without calcification in the right breast | ||||||

| 2009 | Basu et al. [3] | 35 | Humerus | Breast | 99mTc-MDP bone scan | Not available |

| Focal tracer uptake outside the skeletal outline | ||||||

| 2010 | Vieira et al. [4] | 51 | Femur | Breast, lung | Breast imaging – Not available | High-grade pleomorphic sarcoma |

| 2013 | Chan et al. [5] | 16 | Tibia | Breast, lung, peritoneum | Chest and abdomen CT | Not available |

| Multiple discrete, round nodules with dense calcification in both breasts | ||||||

| Current case | 58 | Tibia | Breast, mediastinum | Chest CT | Conventional osteosarcoma, osteoblastic type | |

| Dense calcified masses in breast and mediastinum | ||||||

| Breast US | ||||||

| Dense calcified mass with posterior shadowing | ||||||

| Mammography | ||||||

| Dense calcified mass with spiculated margins |

References

1. Yeh CN, Lin CH, Chen MF. Clinical and ultrasonographic characteristics of breast metastases from extramammary malignancies. Am Surg. 2004; 70:287–290.

2. Mun SH, Ko EY, Han BK, Shin JH, Kim SJ, Cho EY. Breast metastases from extramammary malignancies: typical and atypical ultrasound features. Korean J Radiol. 2014; 15:20–28.

3. Basu S, Moghe SH, Shet T. Metastasis of humeral osteosarcoma to the contralateral breast detected by 99mTc-MDP skeletal scintigraphy. Jpn J Radiol. 2009; 27:455–457.

4. Vieira SC, Tavares MB, da Cruz Filho AJ, Sousa RB, Dos Santos LG. Metastatic osteosarcoma to the breast: a rare case. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010; 36:891–893.

5. Chan RS, Kumar G, Vijayananthan AA. Rare occurrence of bilateral breast and peritoneal metastases from osteogenic sarcoma. Singapore Med J. 2013; 54:e68–e71.

6. Roebuck DJ, Sato JK, Fahmy J. Breast metastasis in osteosarcoma. Australas Radiol. 1999; 43:108–110.

7. Kim SJ, Choi JA, Lee SH, Choi JY, Hong SH, Chung HW, et al. Imaging findings of extrapulmonary metastases of osteosarcoma. Clin Imaging. 2004; 28:291–300.

8. Salah S, Ahmad R, Sultan I, Yaser S, Shehadeh A. Osteosarcoma with metastasis at initial diagnosis: current outcomes and prognostic factors in the context of a comprehensive cancer center. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014; 2:811–816.

9. Surov A, Fiedler E, Holzhausen HJ, Ruschke K, Schmoll HJ, Spielmann RP. Metastases to the breast from non-mammary malignancies: primary tumors, prevalence, clinical signs, and radiological features. Acad Radiol. 2011; 18:565–574.

10. Momoi H, Wada Y, Sarumaru S, Tamaki N, Gomi T, Kanaya S, et al. Primary osteosarcoma of the breast. Breast Cancer. 2004; 11:396–400.

11. Dragoumis D, Bimpa K, Assimaki A, Tsiftsoglou A. Primary osteogenic sarcoma of the breast. Singapore Med J. 2008; 49:e315–e317.

12. Trihia H, Valavanis C. Histopathology and molecular pathology of bone and extraskeletal osteosarcomas. In : Agarwal M, editor. Osteosarcoma. Rijeka: InTech;2012.

13. Leibl S, Gogg-Kammerer M, Sommersacher A, Denk H, Moinfar F. Metaplastic breast carcinomas: are they of myoepithelial differentiation? Immunohistochemical profile of the sarcomatoid subtype using novel myoepithelial markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005; 29:347–353.

14. Geller DS, Gorlick R. Osteosarcoma: a review of diagnosis, management, and treatment strategies. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010; 8:705–718.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download