INTRODUCTION

Persistent pain after breast cancer treatment (PPBCT) is a common side effect to breast cancer treatment, with a reported prevalence of 24% to 47% [

12345]. With the increased breast cancer survival seen in the recent years, late sequelae to the treatment, such as persistent pain, have become increasingly important to recognize in order to, if possible, administer relevant treatment [

6]. Persistent pain may be severely debilitating for the affected patients as it often causes considerable morbidity in terms of declined physical and emotional well-being [

47891011]. Studies have shown that patients with PPBCT are more likely to report anxiety and depressive symptoms and have a higher level of perceived stress when compared to patients without persistent pain [

4]. Additionally, PPBCT has been identified as the most important predictor of a poor health-related quality of life after breast cancer surgery [

12]. Even though PPBCT is well described in the literature, the exact mechanism of its development remains uncertain and is likely multifactorial [

13]. The persistent pain may result from damage to the nerve fibers during the surgery, or from the adjuvant radiation- or chemotherapy, suggesting a predominantly neuropathic pain character [

1415]; however, evidence for this is currently lacking and few studies have investigated the prevalence of neuropathic pain in this patient group [

131617]. Although several studies have investigated the risk factors associated with developing PPBCT [

12345], most studies published to date have investigated populations consisting of both breast-conserving surgery (BCS) and mastectomized patients, which may give rise to multicollinearity in the analysis of risk factors, due to the inherent correlation between type of breast surgery, tumor related variables, and the adjuvant therapy administered.

The primary purpose of our study was to assess the prevalence and associated treatment-related factors for PPBCT in a population consisting exclusively of patients who underwent unilateral mastectomy. We further aimed to investigate the type of pain experienced by the patients, hypothesizing that most patients reporting pain after a mastectomy would have a clear neuropathic pain component.

RESULTS

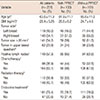

Data from 389 patients, who had undergone a unilateral mastectomy, and were alive and free of recurrence by August 2014, was retrieved from the DBCG database. Exclusion criteria were assessed by reviewing the electronic patient records. Patients who were not treated in accordance with the national DBCG treatment guidelines, had received a breast reconstruction, had emigrated, had died, or had been diagnosed with a recurrence between the time of data extraction and review of electronic records at the end of September 2014, were excluded. In total, 305 patients were eligible for enrolment and were mailed the study questionnaire. Of them, 261 patients (85.6%) returned a completed questionnaire and were included in the study. A flowchart of the inclusion process is depicted in

Figure 1, and detailed patient demographics are shown in

Table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed between the responders and nonresponders to the mailed questionnaire with respect to age, size, and location of the tumor, tumor-positive lymph nodes, or having undergone an axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). The median follow-up time since the mastectomy was 3.0 years (range, 0.8–5.8 years) and the mean age at the time of the breast cancer surgery was 63.6±11.3 years.

The prevalence and location of the pain

Of the 261 patients who responded to the questionnaire, 100 (38.3%) reported pain in at least one of the five assessed areas. The patients most frequently reported pain in the axilla (n=64, 24.5%), followed by the excised breast area (n=53, 20.3%), the medial arm (n=49, 18.8%), ipsilateral thorax (n=44, 16.9%), and the mastectomy scar (n=44, 16.9%). Of the women reporting pain, 26% reported pain in only one of the assessed areas, 74% reported pain in more than one area, 45% reported pain in more than two areas, 24% reported pain in more than three areas, and 11% reported pain in all the five assessed areas (

Table 2).

Intensity and frequency of the pain

The average pain intensity was 4.7±2.3 on the NRS for patients reporting persistent pain. Of the patients reporting pain, 34.0% reported a mild pain (NRS, 1–3), 50.0% reported a moderate pain (NRS, 4–7), while 16.0% reported experiencing severe pain (NRS, 8–10) (

Table 2). Of all patients reporting persistent pain, 58.0% reported to be experiencing pain every day or nearly every day, 20.0% reported experiencing pain 1 to 3 times a week, and 22.0% reported experiencing pain less than once a week. A moderate, but highly significant, positive correlation between the pain intensity and the pain frequency was observed (rs=0.37,

p<0.001).

painDETECT®

The mean PDQ scale score, for the patients who reported to be experiencing persistent pain, was 10.2±6.7. Of the 100 patients who reported experiencing pain, 13.0% (n=13, 5.0% of the total cohort) scored high enough on the PDQ to indicate a “most likely” neuropathic pain, 16.0% (n=16) scored in the “unclear/ambiguous” range, while 71.0% (n=71) scored low on the scale to indicate an “unlikely” neuropathic pain (nociceptive pain). A moderate, but highly significant, positive correlation between reporting higher pain intensity and having a higher score on the PDQ was observed (rs=0.47, p<0.001).

Factors associated with persistent pain

In univariate analysis, a BMI ≥30 kg/m

2, receiving radiation therapy, and receiving an ALND procedure were all significantly associated with PPBCT (

Table 3). Additionally, receiving chemotherapy was associated with persistent pain, with a borderline statistical significance (

p=0.057). In the subsequent multivariate analysis, only a BMI ≥30 kg/m

2 demonstrated a statistically significant association with PPBCT (

Table 3).

Dysesthesia, phantom breast pain, and pain before surgery

One hundred forty-seven (56.3%) enrolled patients reported experiencing cutaneous dysesthesia at the surgical site. A statistically significant association between dysesthesia and experiencing PPBCT was observed (p<0.001). A total of 42 patients (16.1%) reported experiencing phantom breast sensations, and 13 patients (5.0%) reported phantom breast pain. Having phantom breast sensations was significantly associated with reporting PPBCT (p=0.005). A total of 25 patients (9.3%) reported to have experienced preoperative breast pain; however, this was not significantly associated with PPBCT (p=0.058).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated the prevalence of PPBCT in 261 women who had undergone a unilateral mastectomy at our institution between 2009 and 2013. With a median follow-up period of 3.0 years, 38.3% of the participating women reported surgical site pain. In a multiple regression analysis, having a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 was the only independent risk factor for developing PPBCT. Of all patients reporting a persistent pain, neuropathic pain was indicated in only 13.0%, based on the PDQ scores.

The prevalence of PPBCT in the present study corresponds well with the 24% to 47% prevalence rate reported in the literature [

2345]. The large range of the reported prevalence is likely caused by a lack of consistency in the definition of PPBCT used in these studies, especially in terms of the requisite intensity and frequency of the pain. A few studies have used a cutoff value of 3 or 4 on a 0–10 NRS, as this was deemed as clinically relevant pain, whereas other studies have used any nonzero pain value to denote persistent pain [

4]. However, most studies use pain persisting for more than three months after surgery as a cutoff. In the present study, having a BMI ≥30 kg/m

2 was the only variable independently associated with PPBCT. There is no clear consensus in the literature regarding overweight as a risk factor for PPBCT. In concordance with our results, Smith et al. [

21] also observed a correlation between high BMI and persistent pain, while Macdonald et al. [

8] reported that a higher body weight, but not a higher BMI, was associated with persistent pain. However, some other studies reported a lack of association between an increased BMI and a higher risk of developing persistent pain [

91122]. An association between high BMI and PPBCT may possibly be explained by the more extensive surgery required for overweight women, both in terms of the often larger breasts, and a more difficult axillary dissection. Several previous studies have concluded that ALND is associated with developing persistent pain after breast cancer surgery [

3516]. In the present study, in an unadjusted analysis, ALND was significantly associated with persistent pain (

p=0.029); however, this association lost statistical significance in an adjusted multivariate analysis (

p=0.386). The lack of association may be due to the relatively small sample size of the present study.

The mastectomy itself, as well as the ALND/sentinel node biopsy, may cause damage to the intercostobrachial nerve (ICBN) and the thoracic intercostal nerves. This has given rise to the assumption that the PPBCT is mostly neuropathic in nature [

14]. Furthermore, studies often report that some patients describe the pain as burning, shooting, or stabbing, a description consistent with neuropathic pain [

81423]. Contrary to these reports, in our study, most women with PPBCT did not have a neuropathic pain component. Only 13.0% of the women experiencing persistent pain exhibited a clear neuropathic pain component, although a neuropathic pain component could not be excluded in another 16.0% of the enrolled women. Thus, the prevalence of neuropathic pain in our study is lower than the 40% prevalence reported by Bruce et al. [

16], and 32% prevalence reported by Andersen et al. [

17]. This lower prevalence of neuropathic pain may be explained by the difference in the studied population–our study population comprised solely of mastectomized patients, whereas the population studied by Bruce et al. and Andersen et al. consisted predominantly of BCS patients. Furthermore, the length of the follow-up period in our study (mean follow-up period, 3.0 years) was considerably longer than the follow-up period in the studies by Bruce et al. (0.75 years) and Andersen et al. (1.0 year). The longer follow-up period in our study may have increased the risk of a recall bias, which may also have affected the observed neuropathic pain prevalence.

In the present study, we observed a highly significant positive correlation between higher pain intensity and the neuropathic pain score, which is consistent with a previous study by Langford et al. [

13]. Additionally, neuropathic pain in the acute postoperative period has been found to be predictive of experiencing pain a year after the surgery [

17]. The association between developing neuropathic pain after a mastectomy and reporting a higher pain intensity may have considerable clinical relevance in choosing the optimal treatment regimen for individual patients. The low prevalence of neuropathic pain in our study population prohibited further statistical investigation to identify risk factors for developing neuropathic pain after mastectomy; future studies delving in this area would be interesting and relevant.

A few previous studies have used quantitative sensory testing to evaluate the pain components of PPBCT. Vilholm et al. [

24] observed that patients with PPBCT had a higher thermal detection threshold, higher frequency of cold allodynia, and a greater temporal pain summation evoked by repetitive pinprick compared to pain-free patients. Cold allodynia refers to the pain experienced due to mild temperatures that would normally not evoke a pain response in healthy individuals, and temporal pain summation refers to a condition where the patient demonstrates an increase in the perceived pain intensity with repeated stimulation. Furthermore, Gottrup et al. [

25] reported that patients with PPBCT experienced a higher frequency of temporal pain summation on the operated side compared to patients without PPBCT. Both studies thus indicate a role of neuropathic pain in the mechanism of developing PPBCT. However, none of the studies evaluated the prevalence of neuropathic symptoms. Moreover, women with PPBCT often have scar tissue with adhesion to the underlying tissue [

26], and this type of pain is supposedly nociceptive and not neuropathic. The association between PPBCT and more extensive axillary procedures may also be explained in part by the increased scarring from a more extensive procedure, and may not necessarily be due to more damage to the ICBN. Our observation that neuropathic pain plays a minor role in PPBCT is at least to some extent supported by previous studies investigating intentional sparing of the ICBN, that report divergent and inconclusive results [

17272829]. Additionally, Langford et al. [

30] have recently concluded that even though patients with severe persistent breast pain exhibit neuropathic pain symptoms, the pattern of response to the pain quality assessment scale corresponds well to the pattern expected from patients with nonneuropathic pain conditions. Our findings are thus in accordance with the observations of Langford et al. [

30], and further indicate that the pain mechanism for PPBCT patients may be of several different etiologies, and may thus require different approaches for optimal treatment.

In the present study, younger age was not associated with PPBCT. This is in contrast to most available literature where younger age is one of the most consistent factors associated with the development of PPBCT [

35781116]. However, not all studies report a correlation [

10]. Several explanations for this association have been proposed, including that younger women have increased anxiety and a lower tolerance for pain [

21], and that younger women are frequently offered more aggressive adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Radiation therapy was significantly associated with PPBCT in the univariate regression model but did not reach statistical significance in the adjusted model. In this aspect, our results do not concur with relevant literature that identifies radiation therapy as an independent risk factor for PPBCT [

3]. The lack of significance in the multivariate model may be an effect of the lower power. Chemotherapy, as a risk factor for PPBCT, achieved only borderline statistical significance (

p=0.057) in the univariate regression model. This is similar to the results of a previous nationwide study in Denmark, wherein Gärtner et al. [

3] showed that chemotherapy was not independently associated with the risk of developing PPBCT.

In our study, 8.9% of the patients reported experiencing preoperative breast pain, with a borderline significant association between experiencing preoperative pain and reporting PPBCT (

p=0.058). Preoperative pain has previously been investigated as a risk factor for PPBCT, but with contradictory results [

1730]. Furthermore, higher acute postoperative pain scores have also been associated with the development of PPBCT [

911]. These results highlight the need for future prospective studies with longer follow-up period, especially as the acute postoperative pain is, to some extent, a modifiable risk factor.

Some limitations to the current study must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow any inferences of causality. Second, even though the PDQ has shown a high specificity/sensitivity for detecting neuropathic pain, the gold standard for establishing a neuropathic pain diagnosis is a clinical examination. A higher sensitivity would thus require physical examinations to be conducted by appropriately trained personnel, which was beyond the scope of this study, but nevertheless relevant for future studies. The high response rate adds strength to our study, although, the nonresponders may still induce a bias. Additionally, recall bias may be present in the data regarding the experience of preoperative pain. Furthermore, the results from our adjusted analysis of factors associated with PPBCT indicate that our study may not be sufficiently powered to evaluate independently associated factors.

In conclusion, the results of our study show that PPBCT has a high prevalence after mastectomy. A BMI ≥30 kg/m2, receiving radiotherapy, and receiving ALND were all associated with the development of PPBCT; however, a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 was the only factor independently associated with PPBCT. Furthermore, our results reveal that most women with persistent pain after mastectomy do not have a clear neuropathic pain component, indicating that PPBCT may be caused by several different mechanisms, and may thus need different strategies for optimal pain control.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download