Abstract

Microglandular adenosis (MGA) is a rare benign disease that shows an infiltrative growth pattern of small glands, and it may progress to include atypia and carcinoma. Here we report two cases of breast carcinoma arising in MGA. Case 1 was a 44-year-old woman with a previous history of ductal carcinoma in situ in her right breast. During a follow-up, a 1.8 cm mass-like lesion was found in her left breast. An excisional biopsy suggested that the lesion was breast carcinoma. Case 2 was a 57-year-old woman with a 2.9 cm mass in her right breast. A core needle biopsy of the lesion suggested invasive carcinoma. Both patients underwent modified radical mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Both tumors lacked a myoepithelial cell layer and stained positively for S-100, lysozyme, and α1-antitrypsin, which is typical of MGA. Both cases showed invasive carcinoma arising in MGA.

Microglandular adenosis (MGA) is a rare benign disease that causes proliferative glandular lesions in the breast. These benign lesions may progress to a wide spectrum of disease, from atypical microglandular adenosis (AMGA) to carcinoma arising in microglandular adenosis (CAMGA). Although MGA itself is benign, it can cause carcinoma, which can lead to problems if not excised completely. In this study, we report two cases of invasive carcinoma arising in MGA.

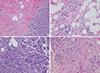

Case 1 was a 44-year-old woman with a previous history of breast-conserving surgery because of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) in her right breast 4 years ago. After breast-conserving surgery, she received radiotherapy on her right breast but no hormonal therapy or chemotherapy. During a regular follow-up, ultrasound examination revealed an abnormal nodular lesion in her left breast. She had no symptoms or signs associated with a breast mass. On physical examination, no palpable mass was found in either breast. Mammography showed heterogeneously dense breast tissue and a newly developed small nodular density at the left upper outer quadrant of the breast (Figure 1A). Ultrasound examination revealed an ill-defined irregular hypoechoic nodule measuring approximately 8 mm and an ill-defined hypoechoic nodule measuring approximately 7 mm (BI-RADS category 4b) at the 1 to 2 o'clock region and 5 cm from the left nipple. Both nodules were adjoining (Figure 1B). Ultrasound guided localization excisional biopsy and frozen section revealed that the lesion was invasive carcinoma. She underwent modified radical mastectomy (MRM) with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). No definite mass-like lesion was found on gross examination (Figure 2). Microscopic examination revealed widely spread round proliferative glands lined by a single layer of flat to cuboidal epithelial cells and lacking a myoepithelial layer, indicating typical MGA. In part of the lesion, the glandular lumen was obliterated by proliferation of monotonous, atypical small cells with frequent mitotic figures, indicating carcinoma in situ. A cord-like arrangement and irregular aggregates of highly atypical cells were scattered in the stroma and extended into the adipose tissue (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining revealed the following: S-100 protein (+), estrogen receptor (ER) (-), progesterone receptor (PR) (+, Allred score 3), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (-), lysozyme (+), α1-antitrpysin (+), calponin (-), and p63 (-). The SLNB showed no evidence of metastasis. The final diagnosis was multifocal invasive carcinoma associated with DCIS (grade 3) arising in MGA with stage 1A, T1 (<1 cm, in the largest one), N0 (0/1), M0, and lymphovascular invasion (-). After surgery, she received adjuvant chemotherapy and hormonal therapy. After 14 months of medical follow-up, no evidence of recurrence has been found.

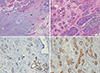

Case 2 was a 57-year-old woman with a palpable mass in her right breast. No other symptoms were associated with the mass. On physical examination, a firm, movable mass measuring approximately 3 cm was palpable at the right upper outer quadrant of the breast. Nipple retraction was observed. She had no medical or familial history of cancer. Mammography revealed a huge mass-like lesion at the right upper breast and ultrasound revealed a lobulating heterogeneous hypoechoic mass measuring 2.6×2.2 cm at the 11 o'clock region of the right breast (Figure 4). Positron emission tomography revealed fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake at a 2.7 cm hypermetabolic mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast (SUVmax: 15.4) and FDG uptake in lymph nodes of the right axilla (level 1). A core needle biopsy of the lesion suggested invasive carcinoma and encapsulated papillary carcinoma. The patient underwent right MRM with SLNB. A well-demarcated solid mass measuring 2.8×2.4 cm was found on gross examination (Figure 5). Microscopic examination revealed encapsulated papillary carcinoma arising in MGA, which exhibited atypia and variable proliferation (approximately 5.2 cm in the largest dimension). Most areas of the MGA were atypical and were lined by large pleomorphic cells with nuclear hyperchromasia and prominent nucleoli. A 0.3×0.25 cm focus of invasion was associated with an altered chondromyxoid stroma adjacent to the encapsulated papillary carcinoma. Typical MGA tubules with intraluminal colloid-like secretory material were found at the more peripheral area of the lesion (Figure 6). IHC staining revealed the followings: S-100 protein (+), smooth muscle myosin-heavy chain (-), ER (-), and PR (-). No metastasis was observed in the sentinel lymph nodes. The final diagnosis was invasive ductal carcinoma (grade 2) associated with encapsulated papillary carcinoma arising in MGA with stage IA, T1 (0.3×0.25 cm), N0 (0/5), M0, and lymphovascular invasion (-). The patient showed no evidence of recurrence on medical follow-up at 19 months. We consulted Dr. Fattaneh Tavassoli, a breast pathologist at the Yale School of Medicine, USA, about these two cases.

Since MGA was first described in 1968, by McDivitt et al. [1], several studies have reported cases of AMGA and CAMGA [2-7]. Both carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma can occur in MGA. In Korea, DCIS arising in MGA was reported by Jeong et al. [8]. To the best of our knowledge, the present cases are the first cases of invasive carcinoma arising in MGA to be reported in Korea. No more than 27% of carcinomas have arisen in MGA [2,6]. Although one report suggested that the incidence of carcinoma could be as high as 64%, it appears to have been affected by bias [9]. Results of IHC staining of carcinoma arising in MGA did not differ significantly from those of MGA. In most cases, results of IHC staining showed positivity for cytokeratin, E-cadherin, and S-100 and negatively for ER, PR, HER2, cystic disease fluid protein (GCDFP)-15, epithelial membrane antigen, smooth muscle actin, CD10, calponin, and p63. α1-Antitrypsin, cathepsin D, and lysozyme may also stain positively in some cases [5]. One of the major differences in IHC staining of MGA from invasive carcinoma is that MGA stains basement membranes with laminin and collagen IV. In MGA and carcinoma in situ, in contrast to invasive carcinoma, basement membranes are preserved. In the two cases presented here, the preliminary pathologic diagnosis was acinic cell carcinoma (ACCA), and it was revised to CAMGA after consultation with Dr. Tavassoli. In some cases, CAMGA is often misdiagnosed as ACCA if MGA goes unrecognized [10,11]. Some CAMGA cells are immunoreactive for amylase, lysozyme, and α1-antichymotrypsin, which are found in ACCA, indicating acinic cell differentiation [10]. In addition to this, both exhibit glandular structures and granularity as well as stain positively for S-100 and antitrypsin, and negatively for ER and PR [5,6]. The biopsy of one of our patients stained positively for lysozyme and α1-antichymotrypsin. Therefore, looking for underlying MGA is essential to making the definite diagnosis. Signs of MGA include regular nuclei, a single layer of cuboidal cells, basal lamina, eosinophilic luminal content, and empty cytoplasm on electron microscopy. In addition, MGA are negative for epithelial membrane antigen and GCDFP-15 in IHC staining. However, ACCA does not show regular nuclei and basal lamina, but shows granular cytoplasm and dense core granules on electron microscopy. It may or may not reveal a single layer of cells, cuboidal cells, luminal content, and GCDFP-15 in IHC staining [4,5,12].

Treatment of CAMGA should be individualized to each patient's stage of disease. If MGA is accompanied by AMGA or CAMGA, it must be completely excised with a negative surgical margin. Incomplete excision of a primary benign MGA lesion can cause recurrence of MGA with development of carcinoma [3]. It is difficult to secure a safety margin because of the insidiously invasive character of MGA, and cases of axillary lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis have been reported [13]. In addition to surgery, radiation therapy should be considered in patients with breast-conserving surgery, and adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered in patients with axillary metastasis or with invasive tumors larger than 1 cm in the absence of nodal metastasis [14]. Despite histopathological and IHC features indicating poor prognoses, most studies have reported relatively favorable prognoses [3,6,7,14,15]. However, longer follow-up periods are needed to determine the exact prognosis of CAMGA.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Radiologic findings of case 1. (A) Mammography showing a small nodular density in the left upper outer quadrant. (B) Ultrasound showing suspicious small nodular hypoechogenic lesion in the left upper outer quadrant. |

| Figure 2Gross findings of case 1. The cut surface of the tumor showing an ill-defined small nodular lesion with no definite mass-like lesion. |

| Figure 3Microscopic findings of case 1. (A) Carcinoma in situ (right side, arrows) arising in typical microglandular adenosis (MGA) (left side) (H&E stain, ×40). (B) Typical MGA (arrowheads) is composed of round glands lined by a single layer of flat to cuboidal epithelial cells and lacks a myoepithelial layer (H&E stain, ×100). (C) Carcinoma in situ area. The glandular lumen is obliterated by a proliferation of low-grade atypical cells with frequent mitoses (H&E stain, ×100). (D) Infiltrating carcinoma (arrowhead) is present in the stroma between normal mammary glands (left side, black arrows) and MGA (right side, blue arrows) (H&E stain, ×100). |

| Figure 4Ultrasound of case 2 showing a 2.6-cm lobulating heterogeneous hypoechoic mass in the right upper outer quadrant. |

| Figure 5Gross finding of case 2. The cut surface of the tumor shows a well-demarcated solid and papillary mass. |

| Figure 6Microscopic findings of case 2. (A) Infiltrating carcinoma (0.3×0.25 cm) with altered chondromyxoid stroma (arrowheads) is seen adjacent to the encapsulated papillary carcinoma (left upper side, black arrows) and atypical microglandular adenosis (MGA) (right side, blue arrows) (H&E stain, ×40). (B) Atypical MGA. Glandular lumens are obscured by the cellular proliferation of large atypical cells with nuclear hyperchromasia and prominent nucleoli. Regular round glands of typical MGA are seen in the background (arrowheads) (H&E stain, ×100). (C) Immunohistochemical staining for smooth muscle myosin-heavy chain (SHH-HC) shows negativity in MGA (left side, arrowheads), which lacks a myoepithelial cell layer. Normal mammary glands were stained positively in myoepithelial cells (right lower side, arrows) (immunohistochemical stain for SMM-HC, ×100). (D) Immunohistochemical staining for S-100 protein is strongly positive in MGA (arrowheads). Entrapped normal mammary gland is negative for S-100 (arrow) (immunohistochemical stain for S-100 protein, ×100). |

References

1. McDivitt RW, Stewart FW, Berg JW. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (U.S.). Universities Associated for Research and Education in Pathology. Tumors of the breast. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Second Serise, Fascicle 2. Wathington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;1968. p. 91.

2. Rosenblum MK, Purrazzella R, Rosen PP. Is microglandular adenosis a precancerous disease? A study of carcinoma arising therein. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986; 10:237–245.

3. Resetkova E, Flanders DJ, Rosen PP. Ten-year follow-up of mammary carcinoma arising in microglandular adenosis treated with breast conservation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003; 127:77–80.

4. Eusebi V, Foschini MP, Betts CM, Gherardi G, Millis RR, Bussolati G, et al. Microglandular adenosis, apocrine adenosis, and tubular carcinoma of the breast: an immunohistochemical comparison. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993; 17:99–109.

5. Koenig C, Dadmanesh F, Bratthauer GL, Tavassoli FA. Carcinoma arising in microglandular adenosis: an immunohistochemical analysis of 20 intraepithelial and invasive neoplasms. Int J Surg Pathol. 2000; 8:303–315.

6. James BA, Cranor ML, Rosen PP. Carcinoma of the breast arising in microglandular adenosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993; 100:507–513.

7. Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. Microglandular adenosis of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 11 cases with ultrastructural observations. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983; 7:731–737.

8. Jeong MS, Kang JH, Kim EK, Woo JJ, Kim HS, An JK. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast arising in microglandular adenosis. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2012; 67:273–276.

9. Khalifeh IM, Albarracin C, Diaz LK, Symmans FW, Edgerton ME, Hwang RF, et al. Clinical, histopathologic, and immunohistochemical features of microglandular adenosis and transition into in situ and invasive carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008; 32:544–552.

10. Damiani S, Pasquinelli G, Lamovec J, Peterse JL, Eusebi V. Acinic cell carcinoma of the breast: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Virchows Arch. 2000; 437:74–81.

11. Coyne JD, Dervan PA. Primary acinic cell carcinoma of the breast. J Clin Pathol. 2002; 55:545–547.

12. Schmitt FC, Ribeiro CA, Alvarenga S, Lopes JM. Primary acinic cell-like carcinoma of the breast: a variant with good prognosis? Histopathology. 2000; 36:286–289.

13. Rosen PP. Microglandular adenosis: a benign lesion simulating invasive mammary carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983; 7:137–144.

14. Rosen PP. Rosen's Breast Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2008. p. 175–186.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download