Abstract

Purpose

Tumor-specific delivery of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), an apoptosis-inducing peptide, at effective doses remains challenging. Herein we demonstrate the utility of a scaffold-based delivery system for sustained therapeutic cell release that capitalizes on the tumor-homing properties of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and their ability to express genetically-introduced therapeutic genes.

Methods

Implants were formed from porous, biocompatible silk scaffolds seeded with full length TRAIL-expressing MSCs (FLT-MSCs). under a doxycycline inducible promoter. In vitro studies with FLT-MSCs demonstrated TRAIL expression and antitumor effects on breast cancer cells. Next, FLT-MSCs were administered to mice using three administration routes (mammary fat pad co-injections, tail vein injections, and subcutaneous implantation on scaffolds).

Results

In vitro cell-specific bioluminescent imaging measured tumor cell specific growth in the presence of stromal cells and demonstrated FLT-MSC inhibition of breast cancer growth. FLT-MSC implants successfully decreased bone and lung metastasis, whereas liver metastasis decreased only with tail vein and co-injection administration routes. Average tumor burden was decreased when doxycycline was used to induce TRAIL expression for co-injection and scaffold groups, as compared to controls with no induced TRAIL expression.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second most lethal for women in the U.S. Moreover, in 2002, breast cancer became the most prevalent cancer in Korean women, comprising 16.8% of all cancers in women, as reported by Lee et al. [1]. The heterogeneous disease is complicated by numerous, diverse, and interconnected host-tumor interactions within tumor microenvironments that influence tumor fate and clinical outcomes. However, most of the mechanisms driving host cell-tumor cell interactions are still not well understood, particularly regarding the roles of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in disease pathogenesis. MSCs have been shown to home to tumors through a number of mechanisms and both negatively and positively affect tumor growth and metastasis in animal models, as shown by Goldstein et al. [2] and Karnoub et al. [3]. MSCs transduced with anticancer peptides are currently being explored for their ability to inhibit tumor growth and progression; if tumor-supportive and off-target effects can be overcome, MSCs may become an important clinical tool for site-specific peptide delivery and inhibition of disease progression, as discussed in our previous review by Reagan and Kaplan [4].

The pro-apoptotic protein ApoL2/TRAIL (Apo Ligand 2, also termed tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) displays potent anticancer effects on TRAIL-responsive cancer cells, specifically those that express Death Receptors 1 and 2, but not on healthy cells, described by Loebinger et al. [5] and Liu et al. [6]. Although TRAIL is currently in clinical trials for anticancer applications, one main challenge with this protein remains: soluble TRAIL is rapidly cleared from the body (half life of approximately 1 hour), shown by El-Deiry [7] and Kagawa et al. [8]. Some studies have addressed the rapid clearance by creating fusion TRAIL-human serum albumin proteins, which have a much longer half-life of around 15 hours, demonstrated by Müller et al. [9], but this technique still provides a much shorter therapeutic window compared to cell-based delivery. Moreover, others (Dörr et al. [10] and Jo et al. [11]) have shown possible off-target toxicity in liver and brain from TRAIL, demonstrating the need for site-specific delivery. A cell-based delivery system to produce TRAIL continually and specifically within the tumor location would greatly increase the efficacy of the protein. The aim of this study was to deliver full length TRAIL (FLT) protein through TRAIL-expressing MSCs (FLT-MSCs) using a novel delivery approach for longer, sustained, and hence more effective delivery. This would greatly improve upon intravenous delivery by creating a much larger tumor-responsive therapeutic window. As shown here, our implant delivery system provides a niche environment for MSCs to reside and be recruited to tumors in response to tumor growth.

Silk is an FDA-approved biomaterial and in scaffold form can be easily modified in terms of size, mechanical strength, porosity, pore-size, and degradation time, lasting from weeks to years, reported by Wang et al. [12]. MSCs have been shown to home from subcutaneously implanted MSC-seeded silk scaffolds to orthotopic breast tumors by Goldstein et al. [2]. Zhao et al. [13] and Ali et al. [14] have recently demonstrated the ability to design and generate biomaterial scaffolds for cell delivery or to induce host immune-cell tracking and activation, but none have proposed or examined the concept of exogenous long-term cell delivery or niche/implant based cell delivery for cancer or other disease applications. Based on the urgent need for inventive anti-cancer strategies, the silk scaffold platform was investigated, as described in this manuscript, for its ability to deliver therapeutic FLT-MSCs and inhibit breast cancer. An array of implants were created and screened in vitro for their ability to harbor FLT-MSCs and the most promising implant was selected to test in vivo in a NOD/SCID breast cancer mouse model. Breast cancer cells (BCCs) found to be TRAIL-sensitive in in vitro work were used in vivo to test the efficacy of therapeutic implants compared to MSC tail vein injections, co-injections or no MSCs and anti-cancer results were observed, suggesting potential for anti-cancer effects from these implants in humans.

FLT-MSCs expressing GFP and TRAIL under a doxycyclineinducible promoter were cultured as previously described by Loebinger et al. [15]. Briefly, the cells were grown in an expansion media of alpha minimum essential medium (αMEM) supplemented with FBS, L-glutamine, and antibiotics. They were fluorescently labeled with Vybrant DiD according to manufacturer's directions (Molecular Probes, Eugene, USA). MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 human breast cancer cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, USA) and cultured as recommended by ATCC. MDA-MB-231 cells were engineered to stably express the firefly-luciferase reporter and dsRed genes using a lentiviral system and cultured as previously described by Goldstein et al. [2]. Media components were from Gibco/Invitrogen (Grand Island, USA) unless otherwise noted. Human MSCs were isolated and grown in expansion media as previously described by Moreau et al. [16]. MSC media consisted of DMEM supplemented with FBS, antibiotics, and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). MSC seeding onto scaffolds and differentiation in osteogenic differentiation media was done as previously described by Moreau et al. [16]. Osteogenic media consisted of α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 0.25 µg/mL fungizone, 0.01 mM non-essential amino acids, 0.05 mM ascorbic acid, 100 nM dexamethasone, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate. All cell culture was performed at 37℃ in 5% CO2.

For CS-BLI assays, methods were performed as previously described by McMillin et al. [17]. 4,000 MDA-MB-231 tumor cells and 2,000 FLT-MSCs were co-seeded into 384 well plates and grown in 50 µL of media consisting of DMEM, 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All samples were grown and read in quadruplicate and bioluminescence was read at 24 hours after seeding using an Envision plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, USA). 5 µL of 2.5 mg/mL luciferin was added to each well and incubated with cells for 30 minutes at 37℃ before reading.

ELISAs were conducted according to manufacturer's instructions using a Quantikine™ Human TRAIL/TNFSF10 Immunoassay Kit (R&D, Minneapolis, USA). 0.5×106 FLT-MSCs were used per group. FLT-MSCs were cultured in expansion media containing 5 µg/mL dexamethasone for 1, 2, 3, or 4 days. To assess how long TRAIL persists after doxycycline removal, FLT-MSCs were cultured in expansion media containing 5 µg/mL doxycycline for 3 days and then withdrawn from doxycycline for 1, 2, or 3 days. Cells were seeded 1 day prior to addition of doxycycline. Cell lysates were stored at -80℃. Samples were normalized to a No-Dox Control group (FLT-MSCs grown without doxycycline) by subtraction of the average control values from each group.

Scaffolds were made from silk solutions (6% water-based silk solution or 17% hexafluoroisopropanol [HFIP]-based silk solution) and NaCl salt crystals (500-600 µm size) and cut into cylinders (6 mm diameter×4 mm height). These were seeded with 1×106 passage 4 (P4) MSCs as previously described to create tissue engineered (TE)-bone [16]. For in vitro screening, samples were differentiated in osteogenic media for 0 (unseeded), 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, or 9 weeks and then re-seeded with 1×106 DiD-labeled P4 MSCs. Samples were then cultured in MSC expansion media for 1 week and analyzed using confocal imaging or trypsinized to remove cells for flow cytometry. Results from in vitro screening demonstrated that naïve scaffolds, not pre-differentiated scaffolds, were best at retaining MSCs. Therefore, for in vivo studies, plain scaffolds were seeded with 1×106 DiD FLT-MSCs 1 day before implantation.

Live-dead and CellTracker DiD fluorescence from MSCs on scaffolds was imaged with a Leica DMIRE2 confocal microscope using a 20× objective after in vitro culture for specified time periods. Scaffolds were removed from culture and stained with a live-dead kit consisting of calcein and ethidium homodimer to label live and dead cells green and red, respectively, as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Grand Island, USA). DiD signal is represented with cyan. Image merging was done using Leica Confocal Software Lite.

Cells were trypsinized and isolated from in vitro scaffold samples and stained for markers expressed by MSCs: CD73 and CD90. PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD-73 IgG1κ antibodies (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, USA), and FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD-90 IgG1κ antibodies (BD Pharmingen) were used as recommended by the manufacturer. 7AAD viability stain (BD Pharmingen) was added to each sample, according to manufacturer's instructions. To block non-specific binding, purified human IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) was added to all samples according to manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometry was conducted on a FACSCalibur, data was collected using CellQuest Pro software and analyzed using FloJo Software (Tree Star, Ashland, USA) v. 7.5.4. Cells were analyzed in a PBS buffer containing 0.05 nM EDTA, 0.5% FBS. Cells were first gated into live and dead cells based on 7AAD staining, and then gated based on the presence or absence of DiD so that only the DiD positive cells would be examined for CD73 and CD90. From the sub-population of live, DiD positive cells, the percentages of CD73 and CD90 positive cells were calculated for each.

Animals were cared for by the Tufts University Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine (DLAM) Tufts Campus Animal Facility under federal, state, local and NIH guidelines for animal care. All experiments were conducted with Tufts University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval (protocol B2010-101). NOD/SCID (NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid) mice aged 6 to 8 weeks old were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, USA) and given one of three treatments of MSCs (implants, tail vein injections, or co-injections) and fed with sterile water containing 0.1% sucrose with or without doxycycline (2 mg/mL final concentration in drinking water, changed twice a week) ad libitum. Control mice were given tumors only (without MSCs) and were given doxycycline in their drinking water. All groups consisted of 5 animals. For the implant group, 2 FLT-MSC implants were implanted subcutaneously above the rotary cuff using dorsal incisions 2 weeks prior to tumor formation. Incisions were closed using a one-layer closure with skin clips, which were removed 10 days later. For the tail vein group, 1×106 DiDFLT-MSCs in 100 µL PBS were injected into the tail vein of restrained mice 10 days after tumor formation and hence the first data points taken for these mice were at week 2 (representing 2 weeks after tumor formation, 4 days after MSC injection). For the co-injection group, 5×105 dsRed/Luc+-MDA-MB-231 cells were injected with 25×105 DiD-FLT-MSCs into mammary fat pads rather than MDA-MB-231 cells alone, which were used to form tumors for the other groups. Control mice had tumor cells, but not MSCs, injected into their mammary fat pads. Like all other groups, they were also given doxycycline in their drinking water. Table 1 summarizes the animal groups utilized.

Sample FLT-MSC implants were cultured and monitored in vivo and in vitro. In vitro samples were grown in MSC expansion media and examined at days 5 and 16 using live-dead imaging as done during the scaffold screening step; live and dead cells are green and red, respectively. In vivo, scaffolds explanted from "scaffold-control mice" were embedded in OCT, snap frozen in acetone and dry ice, sectioned into 10 µm sections and imaged on a DMIRE2 confocal microscope. Scaffolds were removed 2 weeks post-implantation and 8 weeks post-implantation. Images made from z-stacked maximum or average projections.

Tumors were formed by creating a ventral incision in anesthetized mice between the right and left fourth mammary fat pads and injecting 5×105 dsRed/Luc+-MDA-MB-231 cells into the fourth mammary fat pads with (for the co-injection group) or without (for the implant and tail vein groups) 25×105 DiD-FLT-MSCs. For tumor formation and implant surgeries, mice were anesthetized using isofluorane inhalation (1-3%) and the day of tumor formation was considered day 0 of in vivo studies. Cells were injected in 20 µL of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, USA) using a sterile Hamilton syringe fitted with a 22-gauge needle. Incision sites were closed using a one-layer closure with skin clips, which were removed 10 days later.

Six weeks post-tumor cell injection, mice were imaged for DiD fluorescence using the whole animal epi-illuminescence system from Xenogen™/Caliper Lifesciences IVIS Spectrum Imaging System (IVIS, Alameda, USA). Cy5.5 filters and a 23235 EEV camera were used. Fluorescence values are semi-quantitative due to light absorbance and scattering in mouse tissue, which varies based on location and depth of DiD MSCs.

Tumor growth measurements and bioluminescent detection of metastases at the study endpoint were measured at week 1, week 3, and week 6 using bioluminescence imaging of mice as previously described by Moreau et al. [16]. 100 µL D-luciferin (1 mg/mL solution, pH 6.5) were injected into the intraperitoneal cavity and mice were imaged 10 to 15 minutes post-injection. Average flux per mouse (ave flux) are reported and represent an average of the total flux in the tumor regions of interest (ROIs) in each mouse, averaged over all mice in the group. Total flux was generated from measurements of whole animal flux [photons/(sec*cm2*sr)] by using automatic thresholding of tumor ROIs with Living Image version 2.50 analysis software. Metastasis frequency was measured as previously described by Goldstein et al. [2].

All data are represented as mean values with error bars representing standard error on the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, USA). ANOVA was used to compare multiple groups and if ANOVA demonstrated significance, individual comparisons were made using a Dunnett's post-hoc test (for in vivo data, where n=5 mice per group) or Tukey's multiple comparison test (for in vitro data, such as the bioluminescence in vitro assay, n=4), FACS expression assay for CD90 and CD73 (n=3). Symbols represent significance as follows: *p<0.001; †p from 0.001 to 0.01; ‡p from 0.01 to 0.05; p>0.05, not significant.

Characterization of FLT-MSCs using a TRAIL ELISA assay demonstrated that TRAIL expression is tightly regulated by the doxycycline-inducible promoter (Figure 1A). Using cancer cell-specific bioluminescence imaging of direct co-cultures, the highly invasive and metastatic MDA-MB-231 cell line showed significant reductions in cell numbers in response to TRAIL (FLT-MSCs with doxycycline versus without doxycycline groups) after 24 hours (Figure 1B).

Water-based or HFIP-based scaffolds were seeded with MSCs and differentiated in osteogenic media for 6 time periods, or used as plain scaffolds without previous seeding (termed the "0 week" scaffolds) and screened for their abilities to retain MSCs in vitro. For this, the array of differentiated scaffolds were seeded with a second round of MSCs (DiD-labeled MSCs) and examined after 1 week in vitro using confocal imaging and flow cytometric analysis of DiD-MSCs removed from scaffolds, as described by the timeline in Figure 2A. Confocal analysis demonstrated that "0 week" scaffolds (HFIP- or water-based) retained the most DiD MSCs and supported spreading better than all other scaffolds (Figure 2B). Flow cytometry demonstrated no significant differences between implants in their ability to retain CD73 and CD90 expression in seeded DiD MSCs (Figure 2C, D). Hence, 0 week-HFIP implants were selected for in vivo work due to their long in vivo lifetime, as previously shown by Wang et al. [12], and their retention of DiD-MSCs.

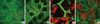

Next, HFIP scaffolds were seeded with FLT-MSCs and analyzed using live-dead analysis with confocal imaging at 5 and 16 days post-seeding in vitro. Resulting images demonstrated attachment, pore infiltration, and high viability of FLT-MSCs on the scaffolds (Figure 3A, B). Scaffolds were then seeded with DiD-fluorescently-labeled FLT-MSCs and implanted subcutaneously into NOD/SCID mice. These similarly demonstrated FLT-MSC retention and pore infiltration after 2 weeks and 8 weeks in vivo (Figure 3C, D, respectively). In vivo experiments were then used to evaluate the ability for silk scaffolds to deliver therapeutic MSCs and produce antitumor effects. Three FLT-MSC delivery mechanisms were compared: co-injections with tumor cells, tail vein injections after tumor formation, and implantation on scaffolds before tumor formation. At 6 weeks after tumor induction, implants demonstrated DiD FLT-MSC retention in vivo by semi-quantitative whole animal fluorescent imaging (Figure 4). Results demonstrate that, for co-injection groups, a strong DiD MSC signal remained within primary tumors (Figure 4A) while for tail vein injection groups a weaker DiD FLT-MSC signal was found only within the tail (Figure 4B). Importantly, fluorescent DiD FLT-MSCs were still strongly fluorescent and concentrated on silk scaffolds in the silk implant groups (Figure 4C, note that these mice have their dorsal side facing upwards, contrasting all other mice). Mice with MDA-MB-231 tumors alone show diffuse, background fluorescence (Figure 4D).

Significant reductions in tumor growth in the co-injection, doxycycline group versus the co-injection, no doxycycline group were found at weeks 1, 3, 6 (Figure 5A). Tumor growth was also substantially inhibited in the implant groups with doxycycline groups compared to no-doxycycline groups at week 3, and in both implant groups (with or without doxycycline) at week 6.

In vivo metastasis results demonstrated the ability of coinjection or tail vein injection with TRAIL-expressing MSCs to decrease bone, lung and liver metastases as compared to BCCs alone (Figure 5B). Therapeutic implants with TRAIL-expressing FLT-MSCs were able to decrease bone and lung metastasis, but slightly increased the frequency of liver metastasis (Figure 5B). Metastasis was assessed by bioluminescent imaging and representative positive and negative organs are shown in Figure 5C. The cell-based peptide delivery system described herein capitalizes on innate tumor-homing and genetic modification technologies involving the production of anticancer proteins and inducible promoters. The system decreased tumor growth and bone and lung metastasis in a xenograft mouse breast cancer model.

Implantation of therapeutic MSCs on a biocompatible implant is a translatable technology for long-term tumor prevention or treatment. In contrast, intravenous or intratumoral injection of FLT-MSCs is not clinically translatable as most primary breast tumors are removed once detected and intravenous delivery leads to rapid clearance. Therefore, the success of the silk implants at inhibiting primary tumor growth and metastasis is crucial as a first step towards development of an innovative new clinical delivery method. Moreover, these studies lay the groundwork for investigations into many other types of scaffold or implant delivery systems. Silk was utilized because it offers no cell-specific instructions and thus fosters retention of stem-like features for MSCs. Silk degradation byproducts are noninflammatory and the slow degradation rate of silk scaffolds, which can be specifically tuned by different formation processes, creates a stable, three dimensional niche for long-term MSC retention that can be degraded in a controlled, predictable manner, described by Wang et al. [12]. In addition, the implants can be designed to deliver other types of factors either through cells on silk implants or directly attached to the silk, such as immunostimulatory factors to generate an immunotherapeutic response against tumors. Growth factors, binding motifs chemically-coupling or embedded, or other ECM components (genetically, as composites, or as coatings), can also be coupled to silk, described by Moreau et al. [16], Bhardwaj et al. [18], and Lü et al. [19].

The trends of our results at week 3 and 6 show drastic, decreases in tumor burden resulting from both TRAIL implants and co-injection doxycycline groups. At later time points, the trend is also found in the tail vein doxycycline groups, by 6 weeks the tail vein injected mice also benefited from TRAIL-MSCs. This lag in efficacy may be due to the fact that FLT-MSCs are administered after tumor formation for the tail vein injection group as opposed to before or during tumor formation for implant and co-injection groups, respectively. Importantly, bone and lung metastases were decreased with the doxycycline tail vein, co-injection and implant groups, although liver metastasis was slightly increased for the implant group, suggesting that not all sites of metastasis may be equally affected by TRAIL therapy. We are not certain why liver metastasis increased in the tumor implant groups, while bone and lung metastasis decreased, but it is possible that this is due to more lung and bone homing and less liver homing by FLT-MSCs. This should be explored with future studies. Specifically, future work should examine biodistribution of FLT-MSCs, perhaps by using Renilla-luciferase labeled MSCs and firefly-luciferase labeled BCCs, as shown previously by Wang et al. [20]. Although our previous work demonstrated tumor-homing of MSCs from silk implants [2], the in vivo experiments performed herein did not allow for tracking of FLT-MSCs. This is due to the fact that the DiD is not a stable dye within the cells and can both leak out and decrease in signal as cells reproduce. MSCs can also differentiate into a number of different cells within tumors, such as pericytes, fibroblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and osteoblasts, among many other cell types, as described by Wang et al., making them impossible to accurately identify without certain gene labeling [20]. Bioluminescent labeling would allow for the most sensitive, non-destructive optical tracking and hence would be useful in future studies to overcome this current limitation.

In sum, we have demonstrated the ability for therapeutic MSCs to significantly decrease tumor growth when administered via a silk implant. It remains to be determined if a leaky TRAIL promoter or a TRAIL-independent mechanism is responsible for the decrease in tumor growth found in the no-doxycycline TRAIL Implant group.

Importantly, we found that co-injections of FLT-MSCs also produce statistically significant reductions in tumor burden in the mice. Although local therapies, such as tumoral injections, here modeled with co-injections, may be utilized to treat unresectable tumors, the majority of breast tumors are resectable. Still, for unresectable tumors, such as gliomas, direct intratumoral injection of TRAIL-MSCs may hold great potential. In breast cancer, the co-injection model, though useful for interpreting direct FLT-MSC/cancer cell interactions, is not a practical delivery system applicable to most patients. Moreover, many life-threatening tumors occur at multiple, distant locations that require systemic treatment and may occur years after primary tumor removal; in fact, 90% of patients die due to metastasis, based on work by Weigelt et al. [21]. Therefore, the implant system holds potential as a clinically viable therapeutic approach, able to deliver MSCs throughout the body over a long time period (as opposed to intravenous MSC injections where MSCs are trapped in the lungs and quickly cleared from the body, shown by Lee et al. [22]). This implant-based delivery is a Trojan-horse delivery method where MSCs are innately co-opted into malignancies, as shown by Goldstein et al. [2]. Here we have shown functional evidence for these implants to distribute anticancer peptides through FLT-MSCs to inhibit tumor growth. The ability to deliver these peptides in a controlled manner, using antibiotic-sensitive promoters, allows for the accumulation of MSCs within tumors before peptide expression, decreasing potentially serious off-target effects. However, MSCs can also display tumor supportive properties, notably, inducing chemotherapy resistance. The factors that determine MSC tumor support or inhibition are mainly unknown and must be elucidated before the use of anticancer MSCs becomes widespread, based on reports by Roodhart et al. [23] and a review from Reagan and Kaplan [4]. Using peptides such as TRAIL that typically affect only transformed cells further localizes the treatment specifically to targeted areas and tilts the scale of MSC influence towards cancer-killing rather than cancer-supporting.

Our breast cancer growth model is orthotopic (within the mammary fat pad) and humanized (utilizing human cells), creating a useful, translational model. However, the xenograft model progresses quickly with metastases arising within weeks of tumor cell injection. Hence, the time-scale of the model inaccurately represents the slower progression seen in most patients. Compared to tail vein delivery, implants showed better, longer-term MSC retention, as evidenced by the whole animal fluorescence imaging, suggesting that scaffolds are an effective administration route over a long disease course. Future studies using mouse models with immune-competent mice would also be beneficial as a more realistic model for effects in humans.

Cellular targets of TRAIL are currently under heavy investigation, with the goal of elucidating the best clinical subgroups for TRAIL therapy and the complete mechanism of TRAIL-induced apoptosis, demonstrated by work by Soria et al. [24]. Our experiments demonstrated TRAIL insensitivity in MCF-7 (of luminal A subtype) and SUM1315 (of an intermediate epithelial/mesenchymal phenotype; positive for vimentin, negative for cytokeratin 5/6) but sensitivity in MDA-MB-231 (basal subtype) cells (data not shown). This finding is corroborated by recent evidence of TRAIL specificity for the cancer stem cell subpopulation by Loebinger et al. [5], and provides optimism for TRAIL treatment specifically for highly invasive, chemoresistant/hormone therapy resistant cancers.

The implant system may prove useful in many stages of cancer progression ranging from pre-diagnosis, for initial detection and treatment in high-risk patients, to post-surgical, as adjuvant therapy to inhibit distant metastases. Therapeutic implants, here TRAIL-expressing MSC-seeded silk scaffolds, comprise a novel, translatable technology with great potential to treat primary or metastatic tumors effectively. Future prototypes may demonstrate their ability to harbor cells that can survey the body for cancer and kill cancer cells before tumors are even clinically detectable. By capitalizing on the various methods of mesenchymal stem cell tracking in vivo, such implants may become both diagnostic and therapeutic tools that bridge prevention and treatment of malignancies.

In summary, we have found that silk scaffolds delivering MSCs that overexpress TRAIL can reduce primary tumor size and bone and lung metastasis. This suggests that anti-cancer implants may hold great therapeutic potential for breast cancer and other cancer patients.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1

In vitro characterization of full length TRAIL-expressing MSCs (FLT-MSCs) and their impact on breast cancer cells. (A) TRAIL protein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of FLT-MSCs exposed to doxycycline (denoted as "dox") for denoted times. Cell specific-bioluminescence assay at 24 hours for MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation in cultures of cancer cells alone, cancer cells with FLT-MSCs, and co-culture with FLT-MSCs and doxycycline. Data is graphed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM), n=3. (B) For direct co-culture imaging of FLT-MSCs and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, breast cancer cells were grown alone, or with FLT-MSCs with and without doxycycline. After 48 hours of co-culture, MDA-MB-231 cells showed significant decreases in cell numbers in the FLT-MSC doxycycline group compared to the FLT-MSC no doxycycline group or the no MSC group. Statistics were done using an ANOVA and a Tukey's multiple comparison test. *p<0.001 (mean±SEM, n=4).

TRAIL=tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; MSC=mesenchymal stem cell; NS=not significant.

|

| Figure 2Scaffold design and characterization. (A) Timeline of in vitro scaffold screening experiment. (B) Representative live-dead confocal imaging of water-based (WB) or solvent-based (HFIP) scaffolds. Samples were pre-differentiated for 0, 3 or 4 weeks, (denoted as 0 wk, 3 wk, or 4 wk, respectively), re-seeded with DiD mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and imaged after 1 week. Cyan, DiD cells; Green, live cells; Red; dead cells and scaffold. All scale bars represent 300 µm. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of CD73 and (D) CD90 expression on DiD MSCs removed from array of scaffolds. No significant differences were found between groups using an ANOVA (mean±SEM, n=4). |

| Figure 3Silk scaffold mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) retention after in vitro and in vivo culture. Live-dead confocal images of scaffolds (A) 5 days and (B) 16 days post-seeding demonstrating good viability in vitro of MSCs on scaffolds. Green, live cells; Red, dead cells and silk scaffold. Frozen section imaged on confocal microscope of full length TRAIL-expressing MSC (FLT-MSC)-seeded HFIP scaffolds removed (C) 2 weeks post-implantation of (D) 8 weeks post-implantation demonstrating retention of DiD FLT-MSCs in vivo. Red, DiD; Green, scaffold autofluorescence. Images made from z-stacked maximum or average projections. All scale bars equal in size and represent 300 µm.

TRAIL=tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

|

| Figure 4DiD full length TRAIL-expressing MSCs (FLT-MSCs) fluorescence at 6 weeks after tumor inoculation for in vivo groups with doxycycline. (A) Co-injection group, (B) tail vein injection group, (C) implant group, and (D) breast cancer cells alone. |

| Figure 5

In vivo tumor growth and metastasis. (A) In vivo tumor growth assessed at weeks 1, 3, and 6 for the following mouse groups with and without doxycycline (Dox): breast cancer cells alone (BCCs), co-injection groups, tail vein injection groups, and Implant groups for mice. Statistics were done using a one-way ANOVA and a post-hoc Dunnett's test: *p<0.001; †0.001<p<0.01; ‡0.05< p<0.01. (B) Metastatic frequency (number of metastases out of total samples) in mouse femurs, liver, and lungs for mice treated with doxycycline. (C) Representative Images of (B): organs positive (left) and negative (right) for metastasis in brain, lung, liver, and bone using unvarying settings for imaging. |

Table 1

Summary of all groups used in in vivo studies

The seven different animal groups are shown here. The positive control group contains mice with no mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). For each full length TRAIL (FLT)-administration route, 5 mice were given doxycycline and 5 were not, to examine specifically the effect of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression by MSCs on tumor growth.

BCCs=breast cancer cells; MFP=mammary fat pad; Dox=doxycycline 2 mg/mL.

References

1. Lee JH, Yim SH, Won YJ, Jung KW, Son BH, Lee HD, et al. Population-based breast cancer statistics in Korea during 1993-2002: incidence, mortality, and survival. J Korean Med Sci. 2007. 22:Suppl. S11–S16.

2. Goldstein RH, Reagan MR, Anderson K, Kaplan DL, Rosenblatt M. Human bone marrow-derived MSCs can home to orthotopic breast cancer tumors and promote bone metastasis. Cancer Res. 2010. 70:10044–10050.

3. Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, Bell GW, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2007. 449:557–563.

4. Reagan MR, Kaplan DL. Concise review. Mesenchymal stem cell tumor-homing: detection methods in disease model systems. Stem Cells. 2011. 29:920–927.

5. Loebinger MR, Kyrtatos PG, Turmaine M, Price AN, Pankhurst Q, Lythgoe MF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of mesenchymal stem cells homing to pulmonary metastases using biocompatible magnetic nanoparticles. Cancer Res. 2009. 69:8862–8867.

6. Liu Y, Lang F, Xie X, Prabhu S, Xu J, Sampath D, et al. Efficacy of adenovirally expressed soluble TRAIL in human glioma organotypic slice culture and glioma xenografts. Cell Death Dis. 2011. 2:e121.

7. El-Deiry WS. Death Receptors in Cancer Therapy. 2005. Totowa: Humana Press;374.

8. Kagawa S, He C, Gu J, Koch P, Rha SJ, Roth JA, et al. Antitumor activity and bystander effects of the tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) gene. Cancer Res. 2001. 61:3330–3338.

9. Müller N, Schneider B, Pfizenmaier K, Wajant H. Superior serum half life of albumin tagged TNF ligands. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010. 396:793–799.

10. Dörr J, Bechmann I, Waiczies S, Aktas O, Walczak H, Krammer PH, et al. Lack of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand but presence of its receptors in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2002. 22:RC209.

11. Jo M, Kim TH, Seol DW, Esplen JE, Dorko K, Billiar TR, et al. Apoptosis induced in normal human hepatocytes by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Nat Med. 2000. 6:564–567.

12. Wang Y, Rudym DD, Walsh A, Abrahamsen L, Kim HJ, Kim HS, et al. In vivo degradation of three-dimensional silk fibroin scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008. 29:3415–3428.

13. Zhao X, Kim J, Cezar CA, Huebsch N, Lee K, Bouhadir K, et al. Active scaffolds for on-demand drug and cell delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011. 108:67–72.

14. Ali OA, Huebsch N, Cao L, Dranoff G, Mooney DJ. Infection-mimicking materials to program dendritic cells in situ. Nat Mater. 2009. 8:151–158.

15. Loebinger MR, Eddaoudi A, Davies D, Janes SM. Mesenchymal stem cell delivery of TRAIL can eliminate metastatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2009. 69:4134–4142.

16. Moreau JE, Anderson K, Mauney JR, Nguyen T, Kaplan DL, Rosenblatt M. Tissue-engineered bone serves as a target for metastasis of human breast cancer in a mouse model. Cancer Res. 2007. 67:10304–10308.

17. McMillin DW, Delmore J, Weisberg E, Negri JM, Geer DC, Klippel S, et al. Tumor cell-specific bioluminescence platform to identify stroma-induced changes to anticancer drug activity. Nat Med. 2010. 16:483–489.

18. Bhardwaj N, Nguyen QT, Chen AC, Kaplan DL, Sah RL, Kundu SC. Potential of 3-D tissue constructs engineered from bovine chondrocytes/silk fibroin-chitosan for in vitro cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011. 32:5773–5781.

19. Lü K, Xu L, Xia L, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Kaplan DL, et al. An ectopic study of apatite-coated silk fibroin scaffolds seeded with AdBMP-2-modified canine bMSCs. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2012. 23:509–526.

20. Wang H, Cao F, De A, Cao Y, Contag C, Gambhir SS, et al. Trafficking mesenchymal stem cell engraftment and differentiation in tumor-bearing mice by bioluminescence imaging. Stem Cells. 2009. 27:1548–1558.

21. Weigelt B, Peterse JL, van't Veer LJ. Breast cancer metastasis: markers and models. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005. 5:591–602.

22. Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009. 5:54–63.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download