Abstract

Chylous leakage is an extremely rare complication of surgery for breast cancer. We experienced a case of chylous leakage after axillary lymph node dissection. A 38-year-old woman with invasive ductal carcinoma in the left breast underwent a modified radical mastectomy after four cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The postoperative serosanguinous drainage fluid became "milky" on the fourth postoperative day. After trying conservative management, we re-explored the axilla and ligated the lymphatic trunk. Although the success of many cases supports conservative management, timely surgical intervention represents an alternative in cases where leakage persists or where the output is high.

Chylous leakage can result from damage to the thoracic duct or its branches after surgical procedures of various types, such as neck or thoracic surgery [1]. However, it is an unusual occurrence after axillary surgery. Although the majority of chylous leakage cases after breast surgery are managed conservatively, we chose to do a re-operation because of the presence of a high chyle output. Herein, we reported our experience of a case of chylous leakage after axillary lymph node dissection, that was treated surgically.

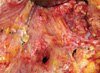

A 38-year-old woman with invasive ductal carcinoma in the left breast underwent a modified radical mastectomy. Four cycles of neoadjuvant adriamycin-docetaxel chemotherapy had been administered before the surgery. The surgical procedure was uneventful and two suction drains were left at the mastectomy site and axilla, in a routine manner. Postoperatively, the drained fluid was serosanguinous in nature. However, it became "milky" on the fourth postoperative day. Analysis of the fluid was compatible with chyle (milky color, protein, 3,400 mg/dL; triglycerides, 784 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 61 mg/dL; and lymphocyte dominance). Initially, we tried conservative management with closed suction drainage, a compressive bandage, and limitation of oral intake; however, the daily output of the drain increased to 700 mL by the seventh postoperative day. Therefore, we re-explored the axilla and observed that the clear fluid was running from a single duct located just below the lateral pectoral bundle branch (Figure 1). We ligated the duct and reinforced the suspicious site 3-4 cm below the duct using a mass ligature. After the re-exploration, the daily output of the drain decreased to 80 mL, although it remained slightly milky in nature. We removed the drain 9 days later. The pathology report confirmed a 1.5-cm, poorly differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma and one metastatic lymph node of 15 lymph nodes evaluated.

Chylous leakage seldom occurs after axillary surgery because the axilla is anatomically remote from the thoracic duct. The reported incidence of chylous leakage after neck surgery is 1-3% and its incidence after surgery for breast cancer is ~0.5% [2,3].

To prevent and control this complication, it is important to determine the location of the chyle leakage. The anatomy of the thoracic duct is well documented and there are numerous variations in the pattern and site of the thoracic duct in the venous system [4]. It has been reported that more than two terminal ducts exist in 7-20% of cases and one case with a thoracic duct that emptied into the right internal jugular vein was described [4,5]. A rare anatomical variation of the lymphatic trunk, posteroinferior to the axillary vein, was supposed to be the cause of the chylous leak after mastectomy [6].

It is very difficult to predict injury to the lymphatic trunks preoperatively or to recognize it during surgery because of its rare occurrence in axillary surgery and the absence of well-known risk factors.

Chylous leakage is usually diagnosed by the typical "milky" drainage fluid after surgery and is confirmed by biochemical analysis of the electrolyte, protein, and fat content of the fluid, which, in these cases, are compatible with chyle. Lymphoscintigraphy or computed tomography are also helpful for the confirmation of chyle collection [7].

Nakajima et al. [3] reported that they did not find any characteristic risk factors after analysis of four cases, although others mentioned previously the effects of wound seroma or obesity [8].

The initial management of chylous leakage should be conservative, including adequate drainage, diet control, and treatment with intravenous octreotide and oral injection of tetracycline hydrochloride [9]. It can also be managed successfully without special dietary control [3].

However, some authors advocate that timely or early re-exploration should be used to manage chylous fistulas, considering the prolongation of the hospital stay and morbidity [2].

Surgical indications can vary depending on the site of the chylous leakage. It is considered when pleural drainage is greater than 1 L per day for more than 5 days in cases of chylothorax or with continuous drainage over 500-600 mL per day without improvement [1,10]. However, an early surgical approach can easily be considered in breast surgery because the risk associated with re-exploration of the superficial chest wall and axilla is not very high.

Surgical management consists of direct ligation of the injured lymphatic channel, if it can be seen during exploration, and plugging with gel foam, other packing materials, or with glue or local muscle rotation flaps [2].

Awareness of this unusual complication after breast surgery should make it possible to avoid or recognize the injury to the thoracic duct during surgery.

Certain ligations in the deep axillary area can prevent this complication [3]. Thus, we suggest an even more careful dissection and ligation in cases where the patient has massive axillary metastasis. In addition, a timely surgical approach may represent an alternative, because of its low morbidity and because it avoids delaying subsequent oncologic treatments, even though many cases were treated conservatively.

Figures and Tables

References

2. Fitz-Hugh GS, Cowgill R. Chylous fistula. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970. 91:543–547.

3. Nakajima E, Iwata H, Iwase T, Murai H, Mizutani M, Miura S, et al. Four cases of chylous fistula after breast cancer resection. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004. 83:11–14.

4. Gottlieb MI, Greenfield J. Variations in the terminal portion of the human thoracic duct. AMA Arch Surg. 1956. 73:955–959.

5. Shimada K, Sato I. Morphological and histological analysis of the thoracic duct at the jugulo-subclavian junction in Japanese cadavers. Clin Anat. 1997. 10:163–172.

6. Purkayastha J, Hazarika S, Deo SV, Kar M, Shukla NK. Post-mastectomy chylous fistula: anatomical and clinical implications. Clin Anat. 2004. 17:413–415.

7. Abdelrazeq AS. Lymphoscintigraphic demonstration of chylous leak after axillary lymph node dissection. Clin Nucl Med. 2005. 30:299–301.

8. Abe M, Iwase T, Takeuchi T, Murai H, Miura S. A randomized controlled trial on the prevention of seroma after partial or total mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection. Breast Cancer. 1998. 5:67–69.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download