This article has been corrected. See "Erratum: Analysis of Infections Occurring in Breast Cancer Patients after Breast Conserving Surgery Using Mesh" in Volume 15 on page 140.

Abstract

Purpose

Breast conserving surgery using mesh can effectively fill the defective space, but there is the risk of infection.

Methods

From June 2007 to August 2010, 243 patients who underwent breast conserving surgery with polyglactin 910 mesh insert for breast cancer at our institution were retrospectively studied.

Results

Infection occurred in 25 (10.3%) of 243 patients. When comparing the infection and non-infection groups in multivariate analysis, there was no significant difference in age, underlying disease, preoperative biopsy methods, mass location, axillary lymph node dissection, operative methods, neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy use, mass size and removed breast volume. The infection appeared more common only in patients with body mass index (BMI) greater than 25. Infection symptoms occurred, on average, 119.5 days after surgery, and the average duration of the required treatment was 34.4 days. Out of 25 patients with postoperative infection complications, 16 (64%) patients underwent incision and drainage with mesh removal, whereas the remaining 9 (36%) only required conservative treatment.

Conclusion

During breast conserving surgery, the risk of infection is increased in patients with high BMI, and should be taken into account when considering insertion of a polyglactin 910 mesh. Patient's age, underlying disease and perioperative treatment methods were not significant risk factors for developing mesh infection. Given that most infections seem to develop symptoms one month after surgery, a long enough observation period should be initiated. Early detection and appropriate conservative treatments may effectively address infections, thus reducing the need for more invasive therapies.

In breast cancer patients, breast conserving surgery has demonstrated good oncologic and cosmetic results [1,2]. However, it still remains difficult to get satisfactory cosmetic results, depending on the tumor size, location, and breast volume [3]. Breast conserving surgery is performed in breast cancer patients requiring radiation therapy, and therefore requires careful decision making with regard to any foreign substance planned for insertion.

Breast conserving surgery using polyglactin 910 mesh (Vicryl®; Ethicon Division, Johnson and Johnson, Somerville, USA), to create a kind of seroma, showed excellent cosmetic results, and relatively few complications. After breast conserving surgery with polyglactin 910 mesh, infection rates of only 3-7% have been reported [4]; however, the risk factors and clinical outcomes have not been adequately addressed. In this study, risk factors for infection and clinical outcomes of patients with polyglactin 910 mesh insertion during breast conserving surgery, were analyzed.

From June 2007 to August 2010, patients who underwent breast conserving surgery with mesh insertion for breast cancer at our institution were retrospectively studied. Patients with benign histologic results, or who had follow-up periods less than 3 months were excluded from the final analysis, because infection generally developed 3 months after operation in our study. In all study patients there were no contraindications to polyglactin 910 mesh insertion. Polyglactin 910 mesh was inserted when severe breast shape deformation was expected following breast conserving surgery, for instance when relatively small breast parenchyma showed large defect, in lower and inner breast cancer.

After washing with normal saline, regardless of the size of the deficient space, folding scalloped polyglactin 910 mesh completely wrapped in oxidized regenerated cellulose (Interceed®; Ethicon Division, Johnson and Johnson, Somerville, USA) was inserted as one polyglactin 910 mesh, in the shape of a triangle. The mesh was placed without being fixed and the skin was sutured in the usual method. Patients who had the mesh inserted did not have drains placed and aspiration was not performed, even in cases with serous fluid retention, during the follow-up observation period. Intravenous antibiotics were administered for 3 days after surgery, using a first generation cephalosporin, followed by 5 days oral antibiotics.

Mesh infection was diagnosed by physical examination performed by a breast specialist during the follow-up period, and infection was defined as patients requiring treatment more than oral and intravascular antibiotics, conservative therapy excluded. Complete cure was defined as antibiotic treatments stopped and sutures removed. Difference in age, body mass index (BMI), underlying disease, preoperative biopsy methods, mass location, operation time, operation methods and perioperative treatment method were analyzed between the group of patients showing postoperative infection and those who did not. In addition, symptoms and their time of onset, treatment methods and treatment duration were analyzed for the infection group.

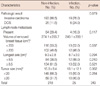

Infection occurred in 25 of 243 (10.3%) reviewed patients. Average age and underlying disease were not significantly different between patients developing infections and those who did not. However, patients with BMI greater than 25 were more likely to develop infection (p=0.007). Based on preoperative biopsy methods, patients diagnosed with the vacuum-assisted biopsy device showed an overall higher incidence in the infection group (n=3, 12.0%), compared with the non-infection group (n=14, 6.4%), but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.248). In both groups, upper-inner quadrant breast surgery was most frequently performed. Breast conserving surgery for a breast mass in the lower-inner quadrant requiring insertion of polyglactin 910 mesh, was more likely to develop an infection (p=0.041) (Table 1).

The average operation time was 86.9 minutes and there was no difference in operative time between the infection group and non-infection group. When frozen biopsy showed a positive margin, no significant difference between the two groups was noted whether axillary lymph node dissection, preoperative mass stain or interoperative re-excision was performed. Similarly, preoperative chemotherapy was not associated with increased infection risk, but patients who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy had more frequent infection (p=0.032). A possible explanation for this finding may be that radiation therapy was started early, when adjuvant chemotherapy was not performed (p=0.042) (Table 2).

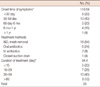

Postoperative biopsy confirmation of either invasive ductal carcinoma or carcinoma in situ, and the presence or absence of lymph node metastasis did not show any relationship with increased infection rate. Likewise, mass size, removed breast volume and long axis of the removed breast were not related to infection rates (Table 3).

Based on univariate analysis, the factors associated with increased infection included BMI over 25, masses located in the low-inner quadrant, patients who have not undergone adjuvant chemotherapy and those who initiated radiation therapy within 100 days postoperatively. When analyzing these parameters independently in our multivariate analysis, the BMI greater than 25 was the only significant risk factor associated with infection (Table 4).

Infection occurred in 25 patients, with most symptoms involving skin redness and pain. The local redness and tenderness can distinguish infection from post-radiation dermal complication. In 3 patients, wound dehiscence and discharge occurred as first symptoms (Table 5). On average, symptoms occurred 119.5 days after surgery. Of the 25 patients with infection, 20 patients (80%) reported symptoms after 30 days, 15 patients (60%) reported symptoms after 60 days, and 5 patients (20%) had symptoms after 6 months. After the symptoms onset, 16 patients (64%) underwent incision and drainage with mesh removal, whereas 6 patients (24%) were treated with oral antibiotics. Intravascular antibiotic treatment was performed in 2 patients and closed drainage was performed in one patient. For patients with infection, the average duration of treatment was 34.4 days. Five patients (20%) were healed by day 15 post-operatively, whereas in 13 patients (52%) more than 30 days were required to clear the infection, of which 3 patients (12%) were completely cured only after 60 days of therapy (Table 6).

Breast conserving surgery has become a standard strategy for breast cancer, especially in early breast cancer. However, breast conserving surgery without volume replacement can lead to cosmetic failure. Reconstructive surgery using either abdominal or back muscle (i.e., the transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous [TRAM] flap, latissimus dorsi flap, etc.) has been the traditional method of volume replacement; however, this technique required long operative and recovery times, was associated with high medical costs and there was increased risk for complications, such as necrosis of the transplanted tissue and abdominal wall herniation [5,6]. When breast conserving surgery is performed over mastectomy, TRAM is difficult to perform. Insertion of the polyglactin 910 mesh has been performed to deliberately form a seroma to fill the defect space. This procedure is simple and easy to learn, with decreased operative time and less burden to the patient. In addition, after 3 months, the polyglactin 910 mesh almost dissolves completely into the body, so follow up breast cancer imaging can more accurately be interpreted [7].

The first report of mesh use in breast cancer was by Largiadèr et al. [8] in 1997, where a nylon mesh with greater omentum was inserted after full-thickness removal of the breast. The insertion of the mesh for cosmetic purposes was described by Amanti et al. [9] in 2002, when they reported insertion of the polyethylene mesh after mastectomy. Then, in 2005, Sanuki et al. [10] published a report of breast conserving surgery using polyglycolic acid and oxidized regenerated cellulose mesh insert.

After polyglactin 910 mesh insertion, improved patient satisfaction and cosmetics has been proven in several studies [11,12]. However, infection after mesh insertion is an area of interest. Infection of mesh material results in breast shape distortion after surgery; in addition, postoperative chemoradiation therapy can be delayed if infections occurs. Therefore patients with diabetes mellitus or immune dysfunction, who are expected to have higher risks for infection, tend not to be offered mesh insertion. In this study, the older aged patients with underlying disease, who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy after insertion of polyglactin 910 mesh, were compared with healthy patients.

The patient's age was not associated with increased infection rates and diabetes patients were not associated with infection. In the univariate analysis, insertion of polyglactin 910 mesh into the low-inner quadrant breast mass, where is relatively small breast parenchyme, was followed by statistically significant infection, but the difference was not significant in multivariate analysis.

There was no statistical difference whether or not a patient underwent axillary lymph node dissection; the procedure is expected to require a mesh insertion into the inner or lower side of the breast, so the incision line for sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary lymph node dissection and for breast parenchyma resection was presented independently. Assessment of the risk of infection when performing single-incision surgery, axillary lymph node dissection and breast conserving surgery using polyglactin 910 mesh requires further studies.

Patients who did not undergo adjuvant chemotherapy appeared to have a higher risk of postoperative infection. This finding may be attributable to earlier initiation of radiation therapy, although multivariate analysis showed no significant difference. However, receiving radiation therapy may lead to either dermatitis or mastitis, so more research is needed regarding postoperative infection.

Post-operative complications, such as bleeding and skin necrosis, can relate with mesh infection; however, in this study, there was no skin necrosis. We had three cases of post-operative bleeding after mesh insertion: one patient showing infection after 32 days and two patients undergoing immediate removal of hematoma and polyglactin 910 mesh. Therefore, analysis of post-operative complications and mesh infection was difficult.

In this study, the definition for mesh infection required both the diagnosis based on physical examination performed by a breast specialist and treatment with oral antibiotics, intravascular antibiotics and drainage. In previous studies, the definition of infection was restricted to incision and drainage for treatment. For this reason, this study seems to show a higher infection risk than previous studies. In this study, the percentage of infected patients who had to remove the mesh and undergo incision and drainage was 64%. If early diagnosis is made and appropriate treatments are initiated conservative treatments can cure the infection.

Based on our univariate analysis, risk factors for mesh infection included a higher BMI, earlier initiation of radiation therapy after surgery, and tumors located in the inner-lower side of the breast. Multivariate analysis of these risk factors, however, resulted in high BMI as the only significant risk factor. Mesh infection was not associated with old age, underlying disease, tumor location, adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or radiation therapy. We consider that perioperative treatment methods and the patients underlying diseases were not related with mesh infection, therefore avoiding mesh insertion seemed not necessary.

In most patients, symptoms occurred after 30 days, with rare instances occurring after 1 year. Adequate follow-up period and early detection with appropriate conservative therapies can improve the outcome results.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Vallejo da Silva A, Destro C, Torres W. Oncoplastic surgery of the breast: rationale and experience of 30 cases. Breast. 2007. 16:411–419.

2. Wang HT, Barone CM, Steigelman MB, Kahlenberg M, Rousseau D, Berger J, et al. Aesthetic outcomes in breast conservation therapy. Aesthet Surg J. 2008. 28:165–170.

3. Fujishiro S, Mitsumori M, Kokubo M, Nagata Y, Sasai K, Mise K, et al. Cosmetic results and complications after breast conserving therapy for early breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2000. 7:57–63.

4. Kim KS, Park MY, Kim WJ, Na KY, Jung YS, Choi YJ, et al. Nationwide survey of the use of absorbable mesh in breast surgery in Korea. J Breast Cancer. 2009. 12:210–214.

5. Spear SL, Mardini S, Ganz JC. Resource cost comparison of implantbased breast reconstruction versus TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003. 112:101–105.

6. Son BH, Lee TJ, Lee SW, Hwang UK, Kwak BS, Ahn SH. Increase of fat necrosis after radiation therapy following mastectomy and immediate TRAM flap reconstruction in high-risk breast cancer patients. J Korean Breast Cancer Soc. 2004. 7:17–21.

7. Bourne RB, Bitar H, Andreae PR, Martin LM, Finlay JB, Marquis F. In-vivo comparison of four absorbable sutures: Vicryl, Dexon Plus, Maxon and PDS. Can J Surg. 1988. 31:43–45.

8. Largiadèr F, Urfer K. Breast wound reconstruction with plastic mesh. Helv Chir Acta. 1977. 44:555–560.

9. Amanti C, Regolo L, Moscaroli A, Lo Russo M, Macchione B, Coppola M, et al. Use of mesh to repair the submuscolar pocket in breast reconstruction: a new possible technique. G Chir. 2002. 23:391–393.

10. Sanuki J, Fukuma E, Wadamori K, Higa K, Sakamoto N, Tsunoda Y. Volume replacement with polyglycolic acid mesh for correcting breast deformity after endoscopic conservative surgery. Clin Breast Cancer. 2005. 6:175.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download