Abstract

Purpose

The patients with metastatic breast cancer are routinely exposed to taxane and anthracycline as neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and palliative chemotherapeutic agents. This study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of using a vinorelbine and ifosfamide (VI) combination treatment in patients with taxane-resistant metastatic breast cancer.

Methods

We evaluated the use of a VI regimen (25 mg/m2 vinorelbine administered on days 1 and 8 plus 2,000 mg/m2 ifosfamide administered on day 1-3 every 3 weeks) for breast cancer patients who evidenced tumor progression after palliative taxane treatment.

Results

Overall, 35 patients were enrolled in this study: Their median age was 50 years (range, 38-72 years). The overall response rate was 40.0% (14 patients; 95% confidence interval [CI], 23-57%). The median time to progression was 4.5 months (95% CI, 3.5-5.4 months). The median overall survival was 18.3 months (95% CI, 12.9-23.6 months). In the 190 cycle of treatment, the incidence of grade ≥3 neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia was 29.3%, 4.2%, and 2.0%, respectively. Neutropenic fever was noted in 6 cycles (3.1%). The non-hematological toxicities were not severe: grade 1 or 2 vomiting was observed in 22.8% of the patients.

Patients with metastatic breast cancer are routinely exposed to anthracycline and taxane as neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and palliative chemotherapeutic agents. Although anthracycline and taxane are the most active first-line drugs for treating breast cancer, many patients will show disease progression and so they require further treatment with other chemotherapeutic agents.(1)

Vinorelbine is a semisynthetic vinca alkaloid that has higher liposolubility and an increased tissue concentration than its analogues.(2) When utilized as a single agent against metastatic breast cancer, vinorelbine has shown response rates from 32% to 50% as a first-line treatment and from 15% to 36% as a second-line treatment.(3-7)

Ifosfamide is an alkylating agent that displays single agent activity for treating advanced breast cancer with response rates up to 30%.(8,9) The drug appears to be less myelotoxic and more advantageous for combination chemotherapy with the availability of the uroprotector agent, Mesna.(10) The preclinical results obtained from studies on different cell types (including C3H mammary carcinoma) showed the superiority of ifosfamide over cyclophosphamide.(11,12) Ifosfamide can be administered at significantly higher doses than cyclophosphamide with considerably much less myelosuppression, and so this permits a higher alkylator dose-intensity for ifosfamide than that for cyclophosphamide. There have been several phase I/II studies that have combined ifosfamide with other agents for treating advanced breast cancer patients, such as doxorubicin,(13) paclitaxel(14) and docetaxel(15,16) and these studies have demonstrated the feasibility of considerably high ifosfamide doses as well as the substantial activity of the employed combinations.

We have conducted this phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of using vinorelbine and ifosfamide combination chemotherapy in patients with taxane-resistance metastatic breast cancer.

To be eligible for this study, the patients were required to have a histologically confirmed diagnosis of carcinoma of the breast, as well as at least one measurable lesion. All the metastatic breast cancer patients were aged ≥18 yr and required to have failed with prior docetaxel-based or paclitaxel-based chemotherapy. Only the patients with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of grade 0-2 were enrolled in this study. Adequate bone marrow function (an absolute neutrophil count [ANC] ≥1,500×103/µL and a platelet count ≥100,000×103/µL), adequate renal function (a serum creatinine level ≤1.5 mg/dL), and adequate hepatic function (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels ≤3×upper limit of normal and a total bilirubin level ≤1.5×upper limit of normal) were required for the enrolled patients. A minimum interval of 4 weeks following completion of adjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy for metastatic disease was required. The patients with active infections, serious or uncontrolled concurrent medical illness, brain metastasis and previous history of other malignancies were excluded from the present study. The local ethics committee approved this study, and informed consent was obtained from all the patients prior to entry into the study.

Primary resistance was defined as progressive disease that occurred during or within 6 months after the completion of treatment in an adjuvant setting, as well as the absence of a documented tumor response in a metastatic setting.

Secondary resistance was defined as disease progression after a documented clinical response during chemotherapy, or disease progression 6 months after the completion of treatment for metastatic disease.

Chemotherapy was administered via a chemoport placed in the subclavian vein or it was directly administered into a peripheral vein. The patients were administered 25 mg/m2 vinorelbine (over a 15-min infusion) on days 1 and 8, and they were administered 2,000 mg/m2 ifosfamide (over a 2-hr infusion) on days 1-3. Mesna (Uromitexan) was administered IV at a dose of 2,000 mg/m2 per day, and this was divided into 4 doses of 500 mg/m2 each, which were administered at the time of ifosfamide infusion and at 3 hr, 6 hr, and 9 hr later. The cycles were repeated every 3 weeks until disease progression if the patient's blood count had returned to acceptable levels (WBC: 3,000×103/µL; platelets: 70,000×103/µL), and the non-hematological toxic effects had resolved to the normal status. The dosage of the subsequent cycles was adjusted according to the toxic effects that developed during the preceding cycle. If the hematological values were not achieved by the date of the scheduled drug administeration, then therapy was delayed in weekly intervals, and if the hematological criteria were not fulfilled after a delay of two weeks, the patient was dropped out from the study. The dosages of vinorelbine and ifosfamide were reduced by 25% during the subsequent cycles if the neutrophil and platelet count nadirs were <500×103/µL and <50,000×103/µL, respectively, or if neutropenic fever developed. In addition, on day 8 of chemotherapy, a complete blood count was conducted prior to vinorelbine treatment. The administration of vinorelbine was omitted for the cases of grade 4 hematological toxicity on day 8. The primary endpoint of this study was the tumor response rate, and the secondary endpoints included the time to progression (TTP), overall survival (OS) and the toxicities. TTP and OS were defined as time from the first day of treatment until the first date of disease progression or death, respectively.

Antiemetic therapy with administering 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (ondansetron) was applied in all cases. A follow-up history taking and physical examinations, tumor measurements and toxicity assessments were conducted prior to each 3-week cycle of therapy. Toxicity was evaluated using the National Cancer Institute-Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC), Version 3.0.

Patients who had received at least two cycles of therapy were assessable for response; all patients who received treatment were assessable for toxicity. A physical examination, complete blood counts, blood chemistry and chest X-rays were acquired after each cycle of chemotherapy. Computed tomography scans were repeated every three cycles or earlier for the cases with clinical deterioration.

The responses were assessed by using WHO criteria. Complete response (CR) is defined as the disappearance of all evidence of disease for at least 1 month and the development of no new lesions. Partial response (PR) indicates a decrease of 50% or greater (compared with pretreatment measurements) in the sum of the products of the two largest perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions and no concomitant growth of new lesions for at least 1 month. Stable disease (SD) indicates a decrease of less than 50% or an increase in tumor size less than 25% over the original measurements. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as any of the following: 1) an increase of 25% or greater over the original measurements in the sum of the products of the two largest perpendicular diameters of any measurable lesions, 2) the appearance of any new lesion, or 3) the reappearance of any lesion that had previously disappeared.

This trial was designed to detect a response rate of 30% as compared to a minimal, clinically meaningful response rate of 10%. The two-stage optimal design proposed by Simon was adopted, with a statistical power of 80% to accept the hypothesis and 5% significance to reject the hypothesis. Allowing for a follow-up loss rate of up to 20%, the total required sample size was 35 patients with measurable disease. The TTP and the OS were calculated from the initiation of treatment to the initial observation of disease progression or death, respectively. All the data was analyzed with SPSS software (version 12.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The prognostic factors for OS, TTP and the response rate (RR) were analyzed using Fisher's exact test, Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses.

Between June 2001 and August 2007, 35 patients who were resistant to taxanes (docetaxel or paclitaxel) were assigned to be treated at the Dong-A University Medical

Center, Busan, South Korea. The characteristics of the 35 patients enrolled in this study are described in Table 1. Their median age was 50 yr (age range, 38-72 yr). The performance status (ECOG) was grade 0-1 in the majority of the patients; six patients (17.1%) were grade 2. All of the enrolled patients (n=35) had received prior anthracycline and taxane combination chemotherapy. Primary resistance to taxane was noted in 17 patients (48.6%), and secondary resistance to taxane was detected in 18 patients (51.4%). In 25 patients (71.4%), the hemoglobin level was in excess of 12 g/dL. The tumor marker CA 15-3 was elevated in 13 patients (37.1%). For the hormonal receptor status, the expression of estrogen receptor (ER) and/or progesterone receptor (PR) was positive in 19 patients (54.3%); HER2 was positive in 10 patients (28.6%). All of the 19 patients with hormone receptor positive tumors had received adjuvant hormonal therapy, but only six of the 19 patients (31.5%) had received prior palliative hormonal therapy. A total of 32 patients (91.4%) had received prior palliative chemotherapy of more than one regimen and a total of 17 patients (48.6%) had received prior palliative chemotherapy of more than two regimens. For metastasis, one organ was involved in 10 patients (28.6%), two organs were involved in 13 patients (37.1%) and three or more organs were involved in 12 patients (34.3%). The lung was the most common metastatic site (23 patients, 65.7%), and the lymph nodes (22 patients, 62.8%), bone (16 patients, 45.7%), liver (10 patients, 28.5%) and the skin and soft tissue (10 patients, 28.5%) were involved in a combined fashion.

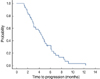

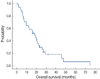

Of the 35 patients who were assessed for their response, a partial response (PR) was noted in 14 patients (40%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 23-57%), stable disease (SD) was detected in 9 patients (25.7%; 95% CI, 10-41%) and progressive disease (PD) was observed in 12 patients (34.3%; 95% CI, 18-51%) (Table 2). The median follow-up duration was 32.9 months. The median TTP was 4.5 months (95% CI, 3.5-5.4 months) (Figure 1). The median OS was 18.3 months (95% CI, 12.9-23.6 months) (Figure 2).

The poor prognostic factors for OS were a serum hemoglobin level below 12 g/dL (p=0.048; 95% CI, 1.101-6.680) and visceral dominant metastasis (p=0.020; 95% CI, 1.254-14.046) on the multivariate Cox regression analysis. Other variations of the patient characteristics were not shown to be significant prognostic factors for the TTP and the OS (Table 3).

A total of 190 treatment cycles were administered to 35 patients with a median number of five cycles (range, 2-12 cycles). The number of dose reduced cycles was 74 (38.9%) among the 190 cycles. The reasons for dose reduction were neutropenia and/or febrile neutropenia. The relative dose intensities were 15 mg/m2/week (90.57%) for vinorelbine and 1,811 mg/m2/week (90.57%) for ifosfamide (Table 2).

An analysis of side effects demonstrated that the toxicities were generally manageable and anemia (grade 1 or 2 in 61.0% of the cycles or 116 of 190 cycles) was the most frequently observed. Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia was observed in 29.3% of the cycles or 56 cycles, but only six episodes of non-fatal neutropenic fever were noted. Grade 1 or 2 vomiting was noted in 8 patients (22.8%), and grade 1 or 2 peripheral sensory neuropathy was observed in 5 patients (14.2%). No treatment-related hepatotoxicity or nephrotoxicity was observed. There was no episode of hemorrhagic cystitis. No treatment-related deaths occurred during the study (Table 4).

Metastatic breast cancer (MBC) has a variable natural history that ranges from an aggressive to an indolent course. There is no standard treatment for metastatic breast cancer. Anthracyclines are utilized as a component of adjuvant chemotherapy for the treatment of early breast cancer. For the cases of metastatic breast cancer, combination chemotherapy with anthracyclines and taxanes has frequently been used as a first-line treatment. The choice of an active chemotherapy for patients with taxane-resistant metastatic breast cancer is not an easy decision.(1)

The combination of vinorelbine and ifosfamide for treating metastatic breast cancer has been previously reported on. For previously untreated MBC, the combination of vinorelbine and ifosfamide has showed an overall response in 58% of the patients, with a complete response occurring in 14%.(18) For the MBC previously treated with anthracyclines, this combination has showed overall response rates ranging from 28% to 52.2%.(19-22) This current study is the first to report on the efficacy of the combination of vinorelbine and ifosfamide that's administered for patients suffering with taxane-resistant metastatic breast cancer.

Our study showed a response rate of 40%, a median TTP of 4.5 months and a median OS of 18.3 months. Our study's response rate was comparable to that reported in the previous studies.(18-22) Several novel microtubule-targeting agents have been demonstrated to be less susceptible to the traditional mechanisms of taxane resistance, such as the multidrug resistance phenotype associated with an increased activity of the P-glycoprotein drug efflux system and the development of structural changes in tubulin. Vinorelbine was included in these therapeutic agents.(23) High doses of ifosfamide might be effective in the salvage setting for the breast cancer patients who have not received prior alkylating agents.(8,9) The median TTP was slightly inferior to that reported in the previous studies.(21,22) The lower median TTP in this study might be attributable to the fact that a total of 27 patients (71.4%) exhibited visceral dominant metastasis, and the relative dose intensities were 90.57% for both vinorelbine and ifosfamide.

In the case of disease progression during the study, salvage chemotherapy was permitted and this was conducted in 26 patients (74.2%) with a variety of drugs. Trastuzumab was used in 6 of the 10 patients who were positive for a HER2 expression. A total of 20 patients exhibited clinical benefits once more with the salvage chemotherapies, and the median OS might have been prolonged due to that phenomenon.

In this study, the prognostic factors associated with overall survival were the serum hemoglobin level and the sites of dominant metastasis. Lower serum hemoglobin level may induce poorer performance status and decreasing compliance due to the hematologic toxicity itself, which make the patients intolerable to the salvage chemotherapy. (24) Visceral dominant metastasis has been proven to be a poor prognostic factor in the previous studies,(25) and visceral dominant metastasis might be negatively associated with the median OS in this study. The positive expression of HER2 was not a significant prognostic factor for survival. Six of the 10 patients (60%) with a HER2 overexpression received trastuzumab as salvage chemotherapy, and that might have been associated with survival.

The present combination of vinorelbine and ifosfamide was well-tolerated in metastatic breast cancer patients, even with three or more pretreated chemotherapy regimens. Myelosuppression, mainly neutropenia, was the dose-limiting side effect, and induced dose modifications in this study. Non-hematological toxicities were only grade 1 or 2 vomiting and peripheral neuropathy.

Our data indicates that the combination of vinorelbine and ifosfamide appears to be effective and it has an acceptable toxicity profile in taxane-resistant, metastatic breast cancer patients. This combination might be incorporated into the chemotherapy options that are available for the previously heavily- treated breast cancer patients.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1A demonstration of the time to progression of the patients. The median time to progression was 4.5 months (95/% CI, 3.5-5.4 months). |

| Figure 2The overall survival of patients. The median overall survival was 18.3 months (95% CI, 12.9-23.6 months). |

References

2. Krikorian A, Rahmani R, Bromet M, Bore P, Cano JP. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of Navelbine. Semin Oncol. 1989. 16:21–25.

3. Hortobagyi GN. Future directions for vinorelbine (Navelbine). Semin Oncol. 1995. 22:80–86.

4. Fumoleau P, Delozier T, Extra JM, Canobbio L, Delgado FM, Hurteloup P. Vinorelbine (Navelbine) in the treatment of breast cancer: the European experience. Semin Oncol. 1995. 22:22–28.

5. Canobbio L, Boccardo F, Pastorino G, Brema F, Martini C, Resasco M, et al. Phase-II study of Navelbine in advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1989. 16:33–36.

6. Gasparini G, Caffo O, Barni S, Frontini L, Testolin A, Guglielmi RB, et al. Vinorelbine is an active antiproliferative agent in pretreated advanced breast cancer patients: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 1994. 12:2094–2101.

7. Mano M. Vinorelbine in the management of breast cancer: new perspectives, revived role in the era of targeted therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006. 32:106–118.

8. Sorio R, Lombardi D, Spazzapan S, La Mura N, Tabaro G, Veronesi A. Ifosfamide in advanced/disseminated breast cancer. Oncology. 2003. 65:55–58.

9. Overmoyer BA. Ifosfamide in the treatment of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996. 23:38–41.

10. Brade WP, Herdrich K, Varini M. Ifosfamide--pharmacology, safety and therapeutic potential. Cancer Treat Rev. 1985. 12:1–47.

11. Goldin A. Ifosfamide in experimental tumor systems. Semin Oncol. 1982. 9:14–23.

12. Buzdar AU, Legha SS, Tashima CK, Yap HY, Hortobagyi GN, Hersh EM, et al. Ifosfamide versus cyclophosphamide in combination drug therapy for metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1979. 63:115–120.

13. Bitran JD, Samuels BL, Marsik S, Gambino A, White L. A phase I study of ifosfamide and doxorubicin with recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in stage IV breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1995. 1:185–188.

14. Bunnell CA, Thompson L, Buswell L, Berkowitz R, Muto M, Sheets E, et al. A Phase I trial of ifosfamide and paclitaxel with granulocytecolony stimulating factor in the treatment of patients with refractory solid tumors. Cancer. 1998. 82:561–566.

15. Kosmas C, Tsavaris N, Malamos N, Stavroyianni N, Gregoriou A, Rokana S, et al. Phase I-II study of docetaxel and ifosfamide combination in patients with anthracycline pretreated advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003. 88:1168–1174.

16. Kosmas C, Tsavaris N, Malamos N, Tsakonas G, Gassiamis A, Polyzos A, et al. Docetaxel-ifosfamide combination in patients with HER2-non-overexpressing advanced breast cancer failing prior anthracyclines. Invest New Drugs. 2007. 25:463–470.

17. Pivot X, Asmar L, Buzdar AU, Valero V, Hortobagyi G. A unified definition of clinical anthracycline resistance breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000. 82:529–534.

18. Leone BA, Vallejo CT, Romero AO, Perez JE, Cuevas MA, Lacava JA, et al. Ifosfamide and vinorelbine as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996. 14:2993–2999.

19. Pronzato P, Queirolo P, Landucci M, Vaira F, Vigani A, Gipponi M, et al. Phase II study of vinorelbine and ifosfamide in anthracycline resistant metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1997. 42:183–186.

20. Aziz Z, Rehman A, Qazi S. Ifosfamide and vinorelbine in metastatic breast cancer in patients with prior anthracycline therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999. 44:S9–S12.

21. Campisi C, Fabi A, Papaldo P, Tomao S, Massidda B, Zappala A, et al. Ifosfamide given by continuous-intravenous infusion in association with vinorelbine in patients with anthracycline-resistant metastatic breast cancer: a phase I-II clinical trial. Ann Oncol. 1998. 9:565–567.

22. Lobo F, Frau A, Barnadas A, Mendez M, Lizon J, Provencio M, et al. Phase II study of ifosfamide plus vinorelbine in metastatic breast cancer patients previously treated with combination chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999. 44:S5–S8.

23. Overmoyer B. Options for the treatment of patients with taxane-refractory metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2008. 8:S61–S70.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download