Abstract

Purpose

Although adjuvant chemotherapy improves the survival of premenopausal breast cancer patients, it could induce the premature menopause. The objective of this study was to investigate the incidence and risk factors of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea (CIA) and recovery for young (< 45-year-old) breast cancer patients.

Methods

We examined patients with primary invasive breast cancer who had been treated with surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy from January 2003 to June 2006. All of the patients were younger than 45 year and they had regular menstruation at the time of diagnosis. Amenorrhea was defined as the absence of menstruation for three consecutive months or a serum follicular stimulating hormone level > 30 mIU/mL.

Results

A total of 324 patients were included in this study. Of these patients, 261 patients (80.6%) developed amenorrhea just after the completion of chemotherapy. During follow-up, 77 patients (29.5%) resumed menstruation. Amenorrhea rates at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after chemotherapy were 72.2%, 66.6%, 58.1%, and 55.5%. Women who recovered from amenorrhea were significantly younger than the women who did not recover (p<0.001). Patients treated with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) less frequently recovered from amenorrhea than patients who were treated with anthracycline or taxane-based chemo- therapy (p<0.001).

Breast cancer is the most common female cancer worldwide, and the incidence of this malady has been continuously increasing in Korea, probably due to the westernization of life style. However, the age distribution of breast cancer patients in Korea is quite different from that of Western countries; about 60 percents of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients are premenopausal, while the premenopausal patients in Western countries constitute only 25 percents of all the breast cancer patients.(1-3)

Many studies have shown that young breast cancer patients have a worse prognosis compared with older patients.(4-7) The poor prognosis of young breast cancer patients is due to advanced disease, poor differentiation, a lesser expression of estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR), a higher nuclear grade and a higher rate of tumor proliferation and tamoxifen resistance.(4,5,7-9) In 2005 at the St. Gallen consensus meetings, young age (<35 yr) was adopted as one of the important factors to categorize the risk of recurrence, and chemotherapy was considered as one of the most important strategies to improve the survival of young premenopausal breast cancer patients.(10,11)

Despite the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy, it could provoke premature menopause and menopausal symptoms such as hot flushing, night sweats, sleep disturbance, palpitation, depression, agitation and vaginitis. Premature menopause also might cause cardiovascular morbidity, early bone mineral loss and fertility impairment.(12) However, there is insufficient information about risk factors for developing chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea (CIA) and the incidence or the pattern of resumption of menstruation after the initial development of CIA.

We conducted this study to investigate the incidence and risk factors for the occurrence of CIA and the recovery from it in young (<45 yr) breast cancer patients.

We retrospectively studied those patients younger than 45 yr with regular menstruation and who were diagnosed with stages I to III primary invasive breast cancer from January 2003 to June 2006 at our hospital. Among them, we excluded the patients with any prior history of chemotherapy due to other cancers, a history of hysterectomy, oophorectomy or chemical ovarian suppression, an incomplete routine chemotherapy schedule, or a change of chemotherapy regimens for any reasons. The patients with poor memory of their menstrual changes were also excluded from this study. A total of 324 patients were finally analyzed.

The information about the age, stage, the clinicopathologic characteristics of the tumor, and the body mass index (BMI) at the time of diagnosis was obtained from the prospectively collected database. Information regarding the patients' menstrual cycles at diagnosis and their changes during and after chemotherapy was obtained from the medical records and one-to-one interviews with the patients.

The definition of CIA was determined as amenorrhea for more than three consecutive months at the completion of chemotherapy.(13) Recovery from CIA was defined as a start of regular menstruation after the occurrence of CIA. If irregular vaginal bleeding appeared after the development of amenorrhea, then the serum follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) level was examined. When the FSH level was 30 mIU/mL or less, then that case was classified into the recovery from CIA group.

The student t-test was used to evaluate the differences in the BMI and age at the time of diagnosis between the groups. The effects of other covariates on CIA were calculated using the Chi-square test. The risk factors for the recovery from amenorrhea were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method with the logistic regression model and the Cox proportional hazard model. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software (version 14.0). All comparisons were considered significant at p-values <0.05.

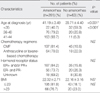

A total of 324 patients were included in this study. The mean age of the patients was 40.1 yr (range: 26-44 yr). The median follow up period was 31.3 months (range: 6-55 months) (Table 1).

The chemotherapy regimens of the 324 patients were cyclophosphamide/methotrexate/5-fluorouracil (CMF) (n=242), doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide (AC) followed by taxane (n=34), AC (n=28), anthracycline plus taxane (n=12), and 5-fluorouracil/doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide (FAC) (n=8) (Table 2). Eight (2.5%) patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Hormonal (anti-estrogen) therapy was administered to 230 (71.0%) patients, and 168 (51.9%) patients received adjuvant radiotherapy.

Of the 324 patients, 261 (80.6%) patients experienced CIA at the time of completion of chemotherapy. The age of the patient at the time of diagnosis was significantly associated with the occurrence of CIA (p<0.001), while the chemotherapy regimen, the hormonal receptor status and the BMI had no association with the initial incidence of CIA (Table 3).

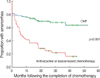

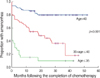

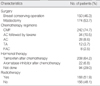

During the follow-up, 77 patients (77/261, 29.5%) resumed menstruation. The amenorrhea rates at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after chemotherapy were 72.2%, 66.6%, 58.1%, and 55.5%, respectively (Figure 1). The patients who recovered from amenorrhea were significantly younger than those who did not (p<0.001, Figure 2). The patients treated with CMF showed the poorest recovery from amenorrhea (p<0.001, Figure 3). At 0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after completion of CMF, the rates of amenorrhea were 81.8%, 77.7%, 74.3%, 69.9%, and 68.0%, respectively. In contrast, the rates of amenorrhea at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after anthracycline or taxane-based chemotherapy were 78.0%, 53.7%, 41.5%, 25.3%, and 22.0%, respectively. A difference in the rates of recovery from CIA between the CMF group and the anthracycline or taxane-based group was observed for the both patient group that was <40 yr old and for the group that was ≥40 yr old (Figure 4). The hormonal receptor status, hormonal therapy, radiotherapy and BMI had no effect on the resumption of menstruation.

Age and chemotherapy regimen was evaluated using multivariate Cox proportional hazards models. On the multivariable analysis, the age of the patients and the chemotherapy regimen were significantly associated with the recovery from CIA (Table 4).

The reported incidence of amenorrhea after chemotherapy has widely varied in a range from 20% to 100%,(14-20) suggesting that there is a need for standardizing the definition of CIA. Although it has been generally reported that older premenopausal patients and the patients who were treated with a CMF regimen have shown a higher incidence of CIA due to the higher cumulative dose of cychlophosphamide,(12-15,17,18,21-23) most of the studies regarding menstrual changes after chemotherapy have not reported sufficient data to determine whether the amenorrhea is permanent or temporary. Furthermore, there has been scant data on the difference in the pattern of resumption of menstruation after initial amenorrhea according to the age of the patients and the chemotherapy regimen.

In this study, when we used the definition of CIA as described above, about 80% of women younger than 45 yr experienced amenorrhea just after completion of chemotherapy. Among them, about 30% resumed their menstruation during the follow-up. An older age was the only risk factor for the initial development of CIA. We also found that although the initial incidence of amenorrhea was not different between women who had been treated with CMF and those treated with an anthracycline or taxane-based regimen, the CMF-induced amenorrhea tends to continue or be permanent while about 80% of the anthracycline or taxane-induced amenorrhea recovered within 5 yr after the development of amenorrhea. Interestingly, this difference in the rates of resumption of menstruation was observed for the women younger than 40 yr as well as for the older women.

The prognostic impact of chemotherapy-induced menopause in young women is still controversial. A recent meta-analysis concerned with the influence of CIA on the prognosis of patients showed that the amenorrheic patients after chemotherapy had a significant survival advantage in 15 of 23 studies, but in the other studies, amenorrhea was not associated with any survival benefit.(24) Furthermore, interpretation of these trials is very difficult because the definition of amenorrhea was heterogeneous, and hormone receptor negative patients were included in many of the studies. In this study, there was no statistically significant relation between CIA and disease recurrence (data was not shown).

The role of adding ovarian suppression to the treatment for young women who remain premenopausal or who resume menstruation after chemotherapy is currently unclear. Several trials had been conducted to evaluate the role of additional ovarian suppression after chemotherapy.(25-28) Most trials have failed to demonstrate the survival advantage of adding ovarian suppression to the standard treatment such as chemotherapy plus tamoxifen. However, in the most of these trials, the menopausal status was assessed prior to chemotherapy. It is assumed that because the majority of the study population had been castrated after chemotherapy, the benefit associated with ovarian suppression might have been precluded in these trials. Ongoing phase III studies using ovarian suppression such as the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT) and Tamoxifen and Exemestane Trail (TEXT) might help advance current knowledge. In these trials, menopausal status was assessed only one time after chemotherapy. However, our finding that resumption of menstruation occurs in about 30% of women with CIA strongly suggests that menopausal status should be monitored for at least 2 or 3 yr after completion of chemotherapy.

CIA is very relevant issue because about 60% of the women diagnosed as breast cancer are premenopausal in Korea.(1,2) The impact of CIA on the prognosis of patients has not been well defined. The role of adding ovarian suppression to chemotherapy and tamoxifen remains unanswered. Because premature menopause is associated with considerable side effects, recognizing which subsets of patients will benefit from the induction of amenorrhea is very critical. Conducting randomized trials that would compare adding ovarian suppression to chemotherapy plus tamoxifen with chemotherapy plus tamoxifen for women who do not achieve permanent amenorrhea with chemotherapy will give us an answer to this critical question.

In the meantime, the type of adjuvant chemotherapy needs to be individualized on the base of primary needs of young women. Alkylating agent-based chemotherapy regimens, such as CMF, induce higher incidence of amenorrhea than anthracycline or taxane-based chemotherapy regimens by affecting the resting oocyte.(29) Because it has been demonstrated that the six cycles of CMF is very equivalent to 4 cycles of AC in terms of the efficacy for the adjuvant treatment of early breast cancers,(30) our finding that CMF-induced amenorrhea recovered poorly regardless of the age of patients suggests that AC may be preferable for those patients who are not married or who have plan to get pregnant. On the other hand, for those patients who are worried about the restoration of ovarian function and finishing a pregnancy, CMF might be a better choice.

The age of a patient at the time of diagnosis was the most important factor for inducing CIA. The patient treated with CMF and the older premenopausal patients recovered poorly from CIA. These results could be helpful to make decisions about the treatment strategies for premenopausal young women, and these results can also aid physicians who are attempting to balance the risk of breast cancer recurrence with the risk of ovarian failure.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 3Menstrual bleeding after completion of chemotherapy according to the type of chemotherapy regimen. |

| Figure 4Menstrual bleeding after completion of chemotherapy according to the type of chemotherapy regimen and the age of patients. |

References

1. Ahn SH, Yoo KY. The Korean Breast Cancer Society. Chronological changes of clinical characteristics in 31,115 new breast cancer patients among Koreans during 1996-2004. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006. 99:209–214.

2. Gong GY, Kim MJ, Shim YH, Kang GH, Ahn SH, Ro JY. Nationwide Korean breast cancer data of 2004 using breast cancer registration program. J Breast Cancer. 2006. 9:151–161.

3. Hankey BF, Miller B, Curtis R, Kosary C. Trends in breast cancer in younger women in contrast to older women. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1994. 16:7–14.

4. Ahn SH, Son BH, Kim SW, Kim SI, Jeong J, Ko SS, et al. Poor outcome of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer at very young age is due to tamoxifen resistance: nationwide survival data in Korea--a report from the Korean breast cancer society. J Clin Oncol. 2007. 25:2360–2368.

5. Xiong Q, Valero V, Kau V, Kau SW, Taylor S, Smith TL, et al. Female patients with breast carcinoma age 30 years and younger have a poor prognosis: the M.D. Anderson cancer center experience. Cancer. 2001. 92:2523–2528.

6. de la Rochefordiere A, Asselain B, Campana F, Scholl SM, Fenton J, Vilcoq JR, et al. Age as prognostic factor in premenopausal breast carcinoma. Lancet. 1993. 341:1039–1043.

7. Nixon AJ, Neuberg D, Hayes DF, Gelman R, Connolly JL, Schnitt S, et al. Relationship of patient age to pathologic features of the tumor and prognosis for patients with stage I or II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994. 12:888–894.

8. Bland KI, Menck HR, Scott-Conner CE, Morrow M, Winchester DJ, Winchester DP. The national cancer data base 10-year survey of breast carcinoma treatment at hospitals in the United States. Cancer. 1998. 83:1262–1273.

9. Walker RA, Lees E, Webb MB, Dearing SJ. Breast carcinomas occurring in young women (< 35 years) are different. Br J Cancer. 1996. 74:1796–1800.

10. Early breast cancer trialists' collaborative group. Effects of adjuvant tamoxifen and of cytotoxic therapy on mortality in early breast cancer. An overview of 61 randomized trials among 28,896 women. N Engl J Med. 1988. 319:1681–1692.

11. Goldhirsch A, Glick JH, Gelber RD, Coates AS, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ, et al. Meeting highlights: international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2005. Ann Oncol. 2005. 16:1569–1583.

12. Minton SE, Munster PN. Chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea and fertility in women undergoing adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Cancer Control. 2002. 9:466–472.

13. Di Cosimo S, Alimonti A, Ferretti G, Sperduti I, Carlini P, Papaldo P, et al. Incidence of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea depending on the timing of treatment by menstrual cycle phase in women with early breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004. 15:1065–1071.

14. Bines J, Oleske DM, Cobleigh MA. Ovarian function in premenopausal women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996. 14:1718–1729.

15. Parulekar WR, Day AG, Ottaway JA, Shepherd LE, Trudeau ME, Bramwell V, et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of amenorrhea during adjuvant therapy in high-risk premenopausal breast cancer: analysis of a national cancer institute of canada clinical trials group study--NCIC CTG MA.5. J Clin Oncol. 2005. 23:6002–6008.

16. Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Castiglione M. The magnitude of endocrine effects of adjuvant chemotherapy for premenopausal breast cancer patients. the international breast cancer study group. Ann Oncol. 1990. 1:183–188.

17. Tham YL, Sexton K, Weiss H, Elledge R, Friedman LC, Kramer R. The rates of chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea in patients treated with adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by a taxane. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007. 30:126–132.

18. Bonadonna G, Moliterni A, Zambetti M, Daidone MG, Pilotti S, Gianni L, et al. 30 years' follow up of randomised studies of adjuvant CMF in operable breast cancer: cohort study. BMJ. 2005. 330:217.

19. Padmanabhan N, Howell A, Rubens RD. Mechanism of action of adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer. Lancet. 1986. 2:411–414.

20. Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, Trudeau M, Hood N. Risk of menopause during the first year after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999. 17:2365–2370.

21. Petrek JA, Naughton MJ, Case LD, Paskett ED, Naftalis EZ, Singletary SE, et al. Incidence, time course, and determinants of menstrual bleeding after breast cancer treatment: a prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2006. 24:1045–1051.

22. Cobleigh MA, Bines J, Harris D. Amenorrhea following adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1995. 14:A158.

23. Vanhuyse M, Fournier C, Bonneterre J. Chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea: influence on disease-free survival and overall survival in receptor-positive premenopausal early breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2005. 16:1283–1288.

24. Walshe JM, Denduluri N, Swain SM. Amenorrhea in premenopausal women after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006. 24:5769–5779.

25. Baum M, Hackshaw A, Houghton J, Rutqvist , Fornander T, Nordenskjold B, et al. Adjuvant goserelin in pre-menopausal patients with early breast cancer: results from the ZIPP study. Eur J Cancer. 2006. 42:895–904.

26. Kaufmann M, Jonat W, Blamey R, Cuzick J, Namer M, Fogelman I, et al. Survival analyses from the ZEBRA study. goserelin (zoladex) versus CMF in premenopausal women with node-positive breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003. 39:1711–1717.

27. Thomson CS, Twelves CJ, Mallon EA, Leake RE. Scottish Cancer Trials Breast Group. Scottish Cancer Therapy Network. Adjuvant ovarian ablation vs CMF chemotherapy in premenopausal breast cancer patients: trial update and impact of immunohistochemical assessment of ER status. Breast. 2002. 11:419–429.

28. Jonat W, Kaufmann M, Sauerbrei W, Blamey R, Cuzick J, Namer M, et al. Goserelin versus cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil as adjuvant therapy in premenopausal patients with nodepositive breast cancer: the zoladex early breast cancer research association study. J Clin Oncol. 2002. 20:4628–4635.

29. Warne GL, Fairley KF, Hobbs JB, Martin FI. Cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian failure. N Engl J Med. 1973. 289:1159–1162.

30. Fisher B, Brown AM, Dimitrov NV, Poisson R, Redmond C, Margolese RG, et al. Two months of doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide with and without interval reinduction therapy compared with 6 months of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil in positive-node breast cancer patients with tamoxifen-nonresponsive tumors: results from the national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project B-15. J Clin Oncol. 1990. 8:1483–1496.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download