Abstract

Purpose

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is a relatively accurate diagnostic method for determining the presence of axillary lymph node metastasis (ALND). SLNB reduces the need for axillary lymph node dissection, thereby decreasing the postoperative axillary morbidity. The present study compared the postoperative axillary morbidity rates during early postoperative days for patients undergoing either SLNB or conventional ALND.

Methods

We conducted a prospective case-control study of breast cancer patients. The degree of axillary morbidity was compared between 28 SLNB patients (Group I) and 38 ALND patients (Group II).

Results

The SLNB group showed decreased arm swelling and restriction of their shoulder motion in comparison with the conventional axillary dissection group (p<0.05). SLNB and additional lymph node sampling did not result in any additional morbidity.

Conclusion

SLNB or lymph node sampling was associated with less axillary morbidity like arm edema, limitation of motion than was conventional ALND. The rate of postoperative axillary morbidity did not differ following lymph node sampling and SLNB. SLNB may be an effective method for diagnosing of axillary lymph node metastasis with decreasing the postoperative axillary morbidity.

In Korea, the recorded incidence of breast cancer has rapidly increasing since the introduction of screening program. In particular, the proportion of early breast cancer and lymph node negative breast cancer has risen. The Korean Breast Cancer Society report that from 2003 to 2004, the proportion of stage 0 and I breast cancer rose from 30.5% to 57.3% and the proportion of node-negative breast cancer was 65.1%.(1)

While prognostic factors for breast cancer include tumor size, age, hormone responsiveness, the most important prognostic factor is still axillary lymph node metastasis. An accurate diagnosis of lymph node metastasis is critical, and decreasing axillary morbidity is very important issue in surgical oncology. Side effects of conventional axillary dissection can range from mild to severe and can be a chronic condition that affects patients' quality of life for years after cancer surgery.(2) Recently, a less invasive procedure, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), has been developed to stage the axilla for invasive breast cancer. The evaluation of morbidity after axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) and SLNB is under investigation in ongoing randomized trials as the NSABP B-32 and the ALMANAC trial.(3) There are many comparisive report between conventional ALND and SLNB for postoperative axillary morbidity. They were almost study about long-term postoperative axillary morbidity after SLNB. Factors affecting axillary morbidity include postoperative radiation therapy, adjuvant chemotherapy, and physical therapy. However, few studies have examined axillary morbidity in the early postoperative period. The present study compared SLNB and conventional axillary dissection in term of their effects on axillary morbidity in the early postoperative period.

Patients were prospectively collected between July and August 2005 at the Asan Medical Center. We enrolled 39 SLNB patients and 27 conventional ALND patients. The indication of SLNB was clinically lymph node negative breast cancer. Exclusion criteria were previous sugery for breast cancer, bilateral breast surgery, or preoperative chemotherapy.

The sentinel lymph node method involved use of a radiocolloid (99m Tc-Antimony trisulfide). On the day of surgery, 0.1 cc radiocolloid (99m Tc-Antimony trisulfide) was injected onto the periareolar area after which lymphoscintigraphy was performed to evaluate the presence of the sentinel lymph node in axillary and internal mammary area. During breast cancer surgery, the sentinel lymph node was detected using a handheld gammma-detection probe (Neo2000®, Model 2100, Neoprobe production. Dublin, USA) and excised. In addition, any grossly suspicious lymph node were excised. The excised sentinel lymph node and suspicious lymph node were evaluated using intraoperative frozen-section analysis. If there was an evidence of metastatic lymph node, a conventional ALND was performed. Patients with palpable metastatic lymph nodes underwent conventional ALND.

No patients had preexcisting problems in the arm, such as edema, decreased range of motion, or pain. Postoperatively, patients were not given any restrictions in their everyday behavior, and were allowed to commence arm exercise as soon as possible. Follow-up examinations were undertaken on postoperative day 5. For measurement of arm swelling, the circumference (in cm) of both arm (upper and lower arm) was measured 10 cm above and 10 cm below the lateral epicondyle of olcecranon, the mean of 3 measurements was recorded.(4) Arm measurement data were analyzed as follow in order to preclude the influence of the dominant arm circumference, and to ensure evaluation only of arm change due to surgery.(5) The upper arm difference=the postoperative circumference of the ipsilateral upper arm minus the postoperative circumference of contralateral upper arm. The lower arm difference=the postoperative circumference of the ipsilateral lower arm minus the postoperative circumference of the contralateral lower arm. The existence of arm swelling was regarded as an upper and lower arm circumference difference of 2 cm or more. For the subjective assessement of arm edema, patients were asked to determine arm swelling on the operated arm compared with the non-operated arm as either none (none, no arm swelling, tightness, or heaviness) or severe (constant arm heaviness, disability, decreased functional activity, huge arm swelling). Numbness was assessed comparing the sensitivities of inner and outer skin area of the upper arm, axilla and chest wall of the operated shoulder with the non-operated shoulder. Numbness was recorded as either none, mild or moderate. A subjective assessment of numbness was undertaken using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (no numbness) to 10 (severe). All patients underwent goniometric measurement of the affected arm by a physiotherapist at each time point. Measurement of the following arm movements was undertaken on postoperative day 5: shoulder flection (0-180°), shoulder extension (0-60°), shoulder abduction (0-180°).(6) Motion restriction was noted using a scale from 0 to 3 (0, no motion restriction; 1, minor restriction; 2, moderate restriction; 3, severe restriction). Pain, paresthesia, and stiffness in the operated arm were evaluated using a visual analog scale ranging from 0 to 10. Arm power was measured with method standardized by American society of hand therapist. In sitting position, shoulder abduction, and elbow flexion, they grip the dynamometer in each hand

For 28 patients (Group I), the sentinel lymph node showed no metastatic disease according to examination of intraoperative frozen section (6-8 sections) or in paraffin sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin staining and anticytokeratin. In those cases, no further axillary dissection was undertaken other than sampling. these patients were compared prospectively with 38 patients who underwent surgery for breast cancer during the same period and who underwent complete axillary dissection (Group II). The 8 patients who underwent only SLNB and 20 patients who underwent both SLNB and non-sentinel lymph node sampling, were compared with the above variable. Study design is shown in Fig 1.

SPSS software for Windows was used for statistical analyses. Frequency distributions were evaluated using Mann-Whitney U-test and Chi-square test. The level of significance was set p<0.05. Normally distributed quantitative variables were analyzed using t-test for independent samples with correction for heteroscedasticity.

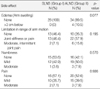

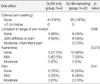

Mean age was 46.1 yr in SLNB (Group I), and 50.2 yr in ALND (Group II) (p=0.074). Group I were likely to have smaller primary tumor than Group II (82.1% vs 63.2% with tumor size <2.0 cm). Group I had more early-stage cancer having stage 0 or I patients than Group II (75% vs 31.5%, p=0.045). Both groups also differed in primary surgery, and Group I were underwent more frequntly breast conserving operation (67.9% vs 39.5%) than Group II. The mean number of sentinel lymph nod dissected was 2.5 (±1.0) lymph nodes in the Group I. In term of the axillary dissection level, 10 patients (15.2%) underwent SLNB only, 20 (30.3%) patients underwent SLNB and sampling, 3 (4.5%) patients underwent sampling only, 4 (6.1%) patients underwent Level I dissection, and 29 patients (43.9%) underwent Level I and II axillary dissection. Mean number of removed axillary lymph node was 4.9 (±2.4) in Group I and 14.3 (±7.6) in Group II. Charateristics of the study population were shown in Table 1.

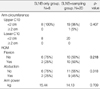

Any Group I patients had not symptom of Arm edema, but 4 (10.5%) patient in Group II were more than 3 cm edema. The incidence of joint pain (more than moderate) was 2 (7.1%) patients in Group II, and 6 patients (15.8%) in Group I. But there was no significant difference of limitation in range of arm motion (p=0.0195). Numbness was reported in 57.9% of the patient after ALND in contrast to 46.5% in the SLNB. There was no significant difference in both Group (Table 2).

By visual analogue scale, there was no difference in arm edema, tingling or numbness, and axillary pain between Group I and II (Table 3). But Group II were slightly more than Group I in limitation of range of motion and arm edema (arm edema: 1.21±0.62 vs 1.0±0.0, p=0.079; Limitation of motion: 1.89±0.65 vs 1.61±0.63, p=0.076).

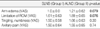

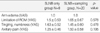

When the difference between both upper arm circumference was more than 2 cm, we regarded it as the existence of difference. The significant difference in upper arm circumference was 1 (3.6%) patients in Group I and 6 (15.8%) patients in Group II (p=0.09), and the significant difference in lower arm circumference was 0 patient (0%) in Group I (13.8%) patients in Group II (p=0.046) (Table 4).

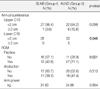

Comparising with the degree of extension and elevation motion in two groups, when there are difference in both shoulder, we defined the restriction. There was little significant difference in abduction, 11 (39.3%) patients in Group I, 18 (47.4%) patients in Group II (p=0.51), but there was significant difference of flection motion 12 (42.9%) patients in Group I, 27 (71.1%) patients in Group II (p=0.021). There was no difference of both arm power in 31.9 kg in Group I, 34.7 kg in Group II (p>0.56).

Recommended surgical care for invasive breast cancer includes removal of the primary tumor and a level I and II ALND. The status of the axillary node helps to determine the prognosis and guide treatment decisions. Unfortunately, side-effects after ALND are relatively common. The sideeffect incidence varies with the length of follow-up, measurement techniques used, and other patient- and treatment-related factors.(7) The side-effect include upper-extremity lymphedema (6-49%), arm numbness/tingling (7-75%), pain (16-54%), impaired shoulder morbidity (4-45%), arm weakness (19-35%), and infections in the breast, chest, or arm.(8, 9)

Recently, a less invasive procedure, SLNB, has been developed to diagnosing the status of axilla in early breast cancer. The sentinel lymph node is the nearest lymph node from the tumor, and the possibility of first metastasis from tumor cell is high, and so the sentinel lymph node is the guard of lymph node metastasis. Morton et al.(10) initially described using blue dye to identify the SLNB in patitents with melanoma. In 1993, Krag et al.(11) first reported the use of SLNB in breast cancer.(11) Subsequent studies by Giuliano et al., using blue dye in patients with early breast cancer, demonstrated its feasibility and accuracy. They found 95.6% accuracy in prediction the status of the axilla, but they also demonstrated that there was a significant learning curve for the technique, with successful identification in only 65.5% of cases.(12) Albertini et al.(13) subsequently reported on the additional use of the radioisotope and a gamma detection probe. They successfully identified the SLNB in 92% of patients by using a combination of blue dye and radioisotope. Other studies have validated the accuracy of SLNB.(14, 15)

SLNB has become an acceptable alternative to ALND for patients with clinically negative lymph node. Surgical practice for staging the axilla for breast cancer is changing ALND to SLNB because SLNB has been found to be accurate in determining whether metastatic disease has spread to the axilla. The availability of SLNB excists in aspects of diagnostic accuracy and decrease of axillary morbidity after conventional axillary dissection. Potential side effect of SLNB are likely to be less than with an ALND because there is less extensive surgery in the axilla. Recently, pubulished data showed no sensory morbidity after SLNB at a median followup of 39 months.(16) Schrenk et al.(17) reported less postoperative arm pain, numbness and arm motion restriction after SLNB at a follow-up period of 15.4 months. The evaluation of morbidity after ALND and SLNB is under investigation in ongoing randomized trials as the NSABP B-32 and the ALMANAC trial. There are many comparisive report between conventional axillary lymph node dissection and SLNB for postoperative axillary morbidity. A single-institution study has shown a reduction in arm numbness, arm pain, arm morbidity and lymphedema after sentinel lymph node dissection as compared with ALND.(16) Another recently pubulished study compared side effects between patients having an SLNB and ALND along with breast conserving surgery and found that SLNB patients had less arm swelling than fewer subjective arm complaint.(18) Swenson et al.(19) announced that SLND decreases the degree of interference with daily life caused by arm symptoms. They repeatedly analyzed with serial time (postoperative 1 month, 6 month, and 12 month). At 1 month, SLND patjents reported less pain, numbness, limitation in rang of motion (ROM), and seromas than ALND patients. At 6 months, SLND patients had less pain, numbness, and arm swelling and at 12 months, SLND patients had less numbness, and arm swelling, and limination in ROM than ALND patients. At 1 months, pain, numbness and limitation in ROM interfered significantly more with daily life for ALND patients. At 6 and 12 months, only numbness interfered more with daily life for ALND patients. On conclusion, SLND was associated with fewer side effects than ALND at all time patients.(19)

Our study corroborates previous work by Schrenk and Swenson that patients experience less than pain, numbness, and ROM restriction after SLND than ALND. Additional axillary lymph node sampling, suspicious and swelling lymph node sampling, did not increased the incidence of axillary morbidity. If sentinel lymph node and suspicious lymph node was founded intraoperatively, additional lymph node sampling may not increase the axillary morbidity. In comparison with previous study, it was short term period of postoperive day, and then it was not influenced with adjuvant therapy, such as radiation therapy, chemotherapy. Our study may be primarily influenced by axillary operation method.

The degree of arm swelling in the early postoperative period is commonly observed and tends to settle spontanously within a matter of weeks.(20) Much of this variation is due to different levels of awareness of the problem, different techniques for measuring arm volume and lack of a universal definition of what degree of swelling constitutes 'lymphedema', as well as genuine differences resulting from variation in clinical practice. But the present study was evaluated in immediate postoperative period, and then there are no effect of spontanous resolution

Kissen and colleagues, reported a subjective prevalence of arm swelling, as noted by either patients or observer, of 14 percent, but on measurement of volume excess compared with the contralateral arm, 25 percent exceeded the 200 mL cut-off that had been adopted for this study.(21)

In the present study, we evaluate arm swelling between subjectively by visual analog scale and objectively by goniometric measurement. In both evaluation, ALND slightly increased arm swelling in comparison to SLNB. In the morbidity of shoulder motion, subjectively ALND didn't increased the limitation of shoulder motion, but objectively increased the limitation of shoulder motion in comparision to SLNB. In our study, Numbness was reported in 57.9% of the patients after ALND in contrast to 46.5% in the SLNB group. There are no significant difference in both group, but it is difficult that there was truly no difference due to limitation in number of patient with additional sampling. We suggest that this may be due to the description of sensory qualities of numbness by word description as 'pain', 'tugging'.

In the present study, we used a validated measurement instruments to specify reliability patients' subjective experience of postoperative morbidity after SLNB in comparison to ALNB. To our knowledge, this is one of the first report to compare various aspect of arm/shoulder morbidity after different types of axillary surgery in early postoperative period. However, despite the analysis of many covariates with different measurement instruments a potential limitation of our study may be the small sample size.

SLNB and sampling results in less axillary morbidity compared to conventional axillary dissection, especiailly in term of arm swelling and restriction of motion. SLNB and suspicious lymph node sampling did not increase postoperative axillary morbidity. SLNB may be effective method for diagnosis of axillary lymph node metastasis with decreasing the postoperative axillary morbidity.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Son BH, Kwack BS, Kim JK, Kim JH, Hong SJ, Lee JS, et al. Changing patterns in the clinical charateristics of Korean patients with breast cancer during the last 15 years. Arch Surg. 2006. 141:155–160.

2. Kuehn T, Klauss W, Darsow M, Regele S, Flock F, Maiterch C, et al. Long term morbidity following axillary dissection in breast cancer patients-clinical assessment, significance for life quality and the impact of demographic, oncologic and therapeutic factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000. 64:275–286.

3. Peintinger F, Reitsamer R, Stranzi H, Ralph G. Comparision of quality of life and arm complaints after axillary lymph node dissection vs sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2003. 89:648–652.

4. Waldman SD. Interventional pain management. 2001. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;196.

5. Gosselink R, Rouffaer L, Vanhelden P, Piot W, Troosters T, Christiaens MR. Recovery of upper limb function after axillary dissection. J Surg Oncol. 2003. 83:204–211.

6. Riddle DL, Rothestein JM, Lamb RL. Goniometric reliability in a clinical setting. Shoulder measurements. Phys Ther. 1987. 67:668–673.

7. Kakuda JT, Stuntz M, Trivedi V, Klein SR, Vargas HI. Objective assessment of axillary morbidity in breast cancer treatment. Am Surg. 1999. 65:995–998.

8. Sener SF, Winchester DJ, Martz CH, Feldman JL, Cavanaugh JA, Winchester DP, et al. Lymphedema after sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Cancer. 2001. 92:748–752.

9. Baron RH, Fey JV, Raboy S, Thaler HT, Borgen PI, Temple LK, et al. Eighteen sensations after breast cancer surgery: a comparion of sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary lymph node dissection. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002. 29:651–659.

10. Morton DL, Wen DR, Wong JH, Economou JS, Cagele LA, Storm FK, et al. Technical details of intraoperative lymphatic mapping for early stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 1992. 124:392–399.

11. Krag D, Weaver D, Ashikaga T, Moffat F, Klimberg VS, Shrirer C, et al. The sentinel node in breast cancer- a multicenter validation study. N Engl J Med. 1998. 339:941–946.

12. Giuliano AE, Kirgan DM, Guenther JM, Morton DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Ann Surg. 1994. 220:391–401.

13. Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, Yeatman T, Balducci L, Ku N, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 1996. 276:1818–1822.

14. McMasters KM, Tuttle TM, Carlson DJ, Brown CM, Noyes RD, Glaser RL, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer: a suitable alternatives to routine axillary dissection in multi-institutional practice when optimal technique is used. J Clin Oncol. 2000. 18:2560–2566.

15. Giuliano AE, Dale PS, Turner RR, Morton DL, Evans SW, Krasne DL. Improved axillary staging of breast cancer with sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995. 222:394–399.

16. Giuliano AE, Haigh PI, Brennan MB, Hansen NM, Kelley MC, Ye W, et al. Prospective observational study of sentinel lymphadenectomy with out further axillary dissection in patients with sentinel nodenegative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000. 18:2553–2559.

17. Schrenk P, Rieger R, Shamiyeh A, Wayand W. Morbidity following a sentinel lymph node biopsy versus axillary lymph node dissection for patients with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2000. 88:608–614.

18. Burak WE, Hollenbeck ST, Zervos EE, Hock KL, Kemp LC, Young DC. Sentinel lymph node biopsy results in less postoperative morbidity compared with axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2002. 183:23–27.

19. Swenson KK, Nissen MJ, Ceronsky C, Swenson L, Lee MW, Tuttle TM. Comparision of side effects between sentinel lymph node and axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002. 9:745–753.

21. Kissin MW, Querci della Rovere G, Easten D, Westbury G. Risk of lymphedema following the treastment of breast cancer. Br J Surg. 1986. 73:580–584.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download