Abstract

Objective

The aim of the study was to identify factors influencing the willingness of healthcare consumers to use personal health records (PHR) and to investigate the requirements for PHR services.

Methods

A face-to-face interview was conducted with 400 healthcare consumers from the 3rd-18th of July 2008 using a structured questionnaire. To identity factors affecting the willingness to use PHR and to pay for PHR services, logistic regression analysis was performed. To investigate the requirements for PHR services according to the willingness of the consumers to use PHR and to pay for PHR services, t-test analysis was conducted.

Results

Of the 400 healthcare consumers, 239 (59.8%) were willing to use PHR and 111 (27.8%) were willing to pay for PHR services. The willingness to use PHR was higher in the elderly, those with a disease, and those with experience to use health information on the Internet, and the willingness to pay for PHR services was higher in those with a relatively high income (p<0.05). The willingness to use PHR was approximately 13.5 (95% CI=1.43-126.55) and 3 times (95% CI=1.18-8.74) higher in those with average monthly household incomes >6,000,000 won and 4,500,000-6,000,000 won, respectively, than in those earning <1,500,000 won, and approximately 1.96 times (95% CI=1.18-3.27) higher in those with experience using health information on the Internet than in those without experience. The willingness to pay for PHR services was approximately 5.9 times (95% CI=1.84-19.06) higher in those with an income of 4,500,000-6,000,000 won than in those with an income <1,500,000 won (p<0.05). Demands for test results, medication history, family history, problem list, genetic information, clinical trial information, and social history were significantly higher in those with a willingness to use PHR and those with a willingness to pay for PHR services than in those without willingness to use PHR and those without a willingness to pay for PHR services (p<0.05). Compared to those without a willingness to pay for PHR services, those with a willingness to pay for PHR services showed a significantly higher demand for all the functions (p<0.01).

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that healthcare consumers potentially have a considerable demand for PHR services, and although it is not recognized and used widely yet, PHR is an essential service. In order to enhance people's awareness of PHR and to promote people to use PHR services, we need efforts and initiatives to execute campaigns and education for people to ease access to the service, and to reduce the gap in service utilization skills.

Today's healthcare services are emphasizing the aspects of disease prevention and health management, and there is increasing demand for lifelong health management focused on the quality of life1-3). With the rise of education level and expansion of healthcare services provision, healthcare consumers have a larger choice of healthcare service and high accessibility to healthcare information. Moreover, as active healthcare service consumers, they are demanding healthcare information and services of healthcare providers, and acquiring information by themselves using various media3-6). This trend is increasing the importance of personal health records (PHR)1 that supports healthcare consumers to be involved in their own health management and to do lifelong health management4)7).

Research on PHR is being conducted actively in developed countries, and PHR systems are being developed by combining computer and information technology to medical services for managing individuals' lifelong health information regardless of time and place4)8-13). In the United Sates, IT companies such as Microsoft, Google and CapMed launched online PHR services, and some medical institutions have provided PHR services such as Indivo, PatientSite and PAMF Online14). In the United Kingdom have been run PHR services such as NHS Direct and Health Space.

In Korea as well, PHR is drawing people's attention and its introduction is being discussed, and National Health Insurance Corporation, some large medical institutions and Internet health service companies are attempting to provide PHR services. In many of such attempts, however, PHR services are provided and PHR systems are built by the provider's arbitrary judgment without sufficient examination of users' requirements or PHR data and functions.

On the other hand, Korea owns world-class communication infrastructure, a high level of informatization, and people with high accessibility to and utilization of information technology15-17), so if a PHR system is built it is expected to be used very actively by healthcare consumers.

However, up to the present, there hasn't been any study on surveying Korean healthcare consumers on their willingness to use PHR, their awareness of PHR, willingness to pay for PHR service, and their requirements for health records and PHR service functions, which are ought to refer to build or provide PHR services.

This study was conducted in order to survey healthcare consumers' willingness to use PHR, to identify factors influencing their use of PHR, and to analyze their requirements for clinical data and PHR service functions.

This study conducted a questionnaire survey in order to find healthcare consumers' needs and requirements for PHR services. We derived factors affecting healthcare consumers' use of PHR and their preferred data and functions.

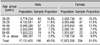

This study surveyed adults aged 20 or over living in Seoul and the capital area. As in Table 1, we sampled around 400 subjects through quota sampling in proportion to the percent distribution of projected population in 2008 in terms of sex and age. The trained interviewers were recruited subjects and assigned them to demographic groups based on age and sex in the survey areas. Before the main survey, a preliminary survey was made with 20 people and the questionnaire was improved through changing the respondents' way of answering and revising words and phrases (Table 1).

This study used a structured questionnaire for its survey. The questionnaire was prepared based on the PHR-System Functional Model, R1 developed by the EHR Technical Committee of HL7 and through discussion among the researchers participating in this study and specialists in related areas using literature review and case study18-23) (Table 2). In order to survey healthcare consumers' requirements for health records, we used all health record items - Problem Lists, Medication List, Test Results, Allergy, Intolerance and Adverse Reaction List, Immunization List, Medical History, Surgical History, Family History, Personal Genetic Information, Social History - of PH.2.5 Manage Historical and Current State Data in PHR-System Functional Model, R1. In order to find their requirements for PHR service functions, we examined sub-functions of Personal Health Functions in PHR-System Functional Model, R1. For functions applicable in the domestic healthcare system, we chose PH.1.2 Manage Account Holder Demographics, PH.1.5 Manage Consents and Authorizations, PH.2.1 Manage Patient Originated Data, PH.3.1 Manage Personal Clinical Measurements and Observations, PH.3.5 Manage Tools and Functions to Assist Self Care, PH.4 Manage Health Education, PH.5 Account Holder Decision Support, PH.6.1 Patient Health Data Derived from Administrative and Financial Sources, PH.6.2 Manage Assessments (Symptoms), PH.6.3 Communications Between Provider and Patient and/or the Patient Representative, and used them in the questionnaire (Table 2).

The questionnaire has a total of 28 questions on the subjects' demographic characteristics, presence of disease in the person and family, experience in the use of Internet health information, whether to know about PHR, expectation of time/cost saving effect of PHR, willingness to use PHR, willingness to pay for PHR service, and requirements for clinical data and PHR service functions. The expectation of the time/cost saving effect of PHR, and requirements for clinical data and PHR service functions were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. The 5-point Likert scale gave 5 point to 'Absolutely yes,' 4 to 'Yes,' 3 to 'Neutral,' 2 to 'No' and 1 to 'Absolutely no.'

This study commissioned the questionnaire survey to a market survey agent in Korea. The survey distributed the questionnaire developed for this study and performed one-to-one individual interviews. The survey was conducted for 16 days from the 3rd to 18th of July, 2008. The interviewees were sampled through quota sampling in proportion to the percent distribution of sex and age in the survey areas.

The subjects' general characteristics were analyzed using frequency analysis and descriptive statistics. Differences in willingness to use PHR and willingness to pay for PHR service according to healthcare consumers' general characteristics were tested using chi-square test, and in order to analyze factors affecting willingness to use PHR and willingness to pay for PHR service we performed backward stepwise logistic regression analysis using the characteristics in Table 3 as independent variables and derived odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for each factor. To investigate their requirements for PHR service according to consumers' willingness to use PHR and to pay for PHR service, t-test analysis was conducted. Collected data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0 and Excel 2007, and statistical tests were made at significant level (α) 0.05.

In the survey of this study, the participants' demographic characteristics are as in Table 3. Of the subjects, 49% were male and 51% were female. The average age was 43.1 (20-77) and the age group between 30-49 was largest as 46.5%. As to education level, 49.3% were high school graduate and 34.3% were university graduates.

As to average monthly household income, 47.4% earned 3,000,000-4,500,000 won, and 31.3% eared 1,500,000-3,000,000 won. The percentage of those who had a disease was 17.8% and that of those whose family had a disease was 21.5%. In addition, 26.8% had experience to use health information on the Internet. Among the subjects, only 8.5% knew about PHR. The respondents expected that the use of PHR would have a positive effect above average on time/cost saving for healthcare providers and consumers. In particular, the time saving effect for healthcare providers was highest as 3.85 out of 5.

Among the 400 healthcare consumers who participated in the survey, 239 (59.8%) had willingness to use PHR (Table 4). Willingness to use PHR was higher in older people, those with high income, those who had a disease, and those with experience to use health information on the Internet. However, no difference was observed in willingness to use PHR according to sex, education level, presence of disease in family, and awareness of PHR.

Among those in their 20s 51.2% had willingness to use PHR, and among those in their 60s or older 65% did. According to average monthly household income, 48.3% of those with below 1,500,000 won and 91.7% of those with over 6,000,000 won had willingness to use. These results show that willingness to use PHR grows higher with increase in age and average monthly household income, and the results appeared statistically significant in chi-square test for linear by linear association (p<0.05). However, sex was not correlated with the use of PHR and the effect of education level was not significant in the result of chi-square test for linear by linear association (p=0.484). The effect of the presence of disease was significant as 70.4% of those with a disease had willingness to use PHR and only 57.4% of those without did (p<0.05). However, there was no significant difference in willingness to use PHR according to the presence of disease in family (p=0.059). According to whether to use health information on the Internet, 71% of those with the experience had willingness to use PHR but only 55.6% of those without did and the difference was significant (p<0.05). However, no significant difference was observed in willingness to use PHR according to the awareness of PHR (p=0.087). The expected time/cost saving of PHR was significantly higher in those with willingness to use PHR. The expected time saving effect of PHR for healthcare providers and consumers was, respectively, 3.9 and 4.06 out of 5 in those with willingness to use PHR, which were significantly higher than 3.76 and 3.47 in those without (p=0.014, p<0.001). The expected cost saving effect for healthcare providers and consumers was also significantly higher in those with willingness to use PHR (p<0.001).

Of the subjects, 111 (27.8%) had willingness to pay fee for the use of PHR. Willingness to pay for PHR service was higher in those with relatively high income. However, no significant difference was observed in willingness to pay for PHR service according to sex, age, education level, the presence of disease in the person and family, experience to use health information on the Internet, and awareness of PHR.

Willingness to pay for PHR service was relatively high in the age group between the 30s-60s, and highest as 33.7% in those in their 30s. According to average monthly household income, the percentage of those with willingness to pay for PHR service was 20.7% in those with below 1,500,000 won, 18.4% in those with 1,500,000-3,000,000 won, but increased to 52.3% and 41.7%, respectively, in those with 4,500,000-6,000,000 won and in those with over 6,000,000 won. This shows the tendency that the higher average monthly household income is the higher willingness to pay for PHR service is, and this tendency was significant in the result of chi-square test for linear by linear association (p<0.001). The expectation of the time/cost saving effect of PHR was significantly higher in those with willingness to pay for PHR. The expected time saving effect of PHR for healthcare providers and consumers was, respectively, 4.05 and 4.22 out of 5 in those with willingness to pay for PHR service, which were significantly higher than 3.76 and 3.67 in those without willingness to pay for PHR (p<0.001). The expected cost saving effect of PHR for healthcare providers and consumers was also significantly higher in those with willingness to pay for PHR (p<0.001).

Table 5 shows the results of logistic regression analysis to identify factors affecting healthcare consumers' willingness to use PHR. According to education level, the odds ratio was around 4.6 times (95% CI=1.24-16.75) higher in middle school graduates than in elementary school graduates (p<0.05). According to average monthly household income, it was around 13.5 times (95% CI=1.43-126.55) and 3 times (95% CI=1.05-8.74) higher, respectively, in those with over 6,000,000 won and in those with 4,500,000-6,000,000 won than in those with 1,500,000 won (p<0.05). According to experience to use health information on the Internet, the odds ratio was around 1.96 times (95% CI=1.18-3.27) higher in those with the experience than in those without (p<0.05). The odds ratio was around 1.93 times (95% CI=0.98-3.81) higher in those with a disease than in those without, and around 1.99 times (95% CI=0.86-4.57) in those who knew about PHR than in those who did not, but the differences were not statistically significant (p=0.058, 0.107). As sex, age, and the presence of disease in family were removed as they were selected as correction factors in backward stepwise regression. The result of Hosmer and Lemeshow test proved the goodness-of-fit of the model (chi-square 2.63, df=8, p=0.96).

Factors affecting willingness to pay for PHR service are as in Table 5. According to average monthly household income, the odds ratio was around 5.9 times (95% CI=1.84-19.06) higher in those with 4,500,000-6,000,000 won than in those with below 1,500,000 won (p<0.05). According to experience to use health information on the Internet, the odds ratio was around 1.6 times (95% CI=0.92-2.63) higher in those with the experience but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.096). The effect of academic level on the paid use of PHR was also insignificant. The result of Hosmer and Lemeshow test proved the goodness-of-fit of the model (chi-square 6.53, df=8, p=0.59).

In this study, healthcare consumers evaluated health records according to their importance (Table 6). Those with willingness to use PHR and those with willingness to pay for PHR service showed high demand as, respectively, over 4 out of 5 for all the health record items presented below. Those without willingness to use PHR and those without willingness to pay for PHR service also showed relatively high demand as, respectively, 3.8 and 3.9 for all the items. Those with willingness to use PHR and those with willingness to pay for PHR service showed the highest demand for test results as 4.56 and 4.64, respectively, and next for surgical history as 4.44 and 4.47. Demand for test results, medication history, family history, problem list, genetic information, clinical trial information, social history (e.g. occupation, drinking, smoking) was significantly higher in those with willingness to use PHR and those with willingness to pay for PHR service than in those without willingness to use and those without willingness to pay for PHR, respectively (p<0.05). For all the clinical data items, demand was relatively higher in those with willingness to pay for PHR than in those with willingness to use PHR.

Table 6 shows the results of evaluating healthcare consumers' requirement for PHR service functions according to importance. Those with willingness to use PHR and those with willingness to pay for PHR service showed high demand of over 4.1 and 4.2, respectively, for all the PHR service function presented below. Those without willingness to use PHR and those without willingness to pay for PHR also showed relatively high demand as 3.8 and 3.9 for all the functions. Those with willingness to use PHR showed the highest demand for 'Manage Patient Originated Data' (4.31) and next in order of 'Communications between Provider and Patient' (4.25), 'Manage Personal Clinic Measurements and Observations' (4.24), and 'Personalized Health Information' (4.24). Those with willingness to pay for PHR service showed the highest demand for 'Manage Patient Originated Data' (4.47) and next in order of 'Health Education' (4.37), 'Communications Between Provider and Patient' (4.36), 'Online Encounter Reservation' (4.35), and 'Manage Personal Clinic Measurements and Observations' (4.35).

Compared to those without willingness to use PHR, those with willingness to use PHR showed significantly higher demand for 'Manage Patient Originated Data', 'Communications Between Provider and Patient', 'Personalized Health Information,' 'Manage Consents and Authorizations,' 'Clinical Decision Support,' 'Online Encounter Reservation,' 'Enable Provider to Request Patient Information in Preparation for the Encounter,' 'Patient Health Data Derived from Administrative and Financial Sources' and 'Manage Assessments (Symptoms)' (p<0.01). Compared to those without willingness to pay for PHR service, those with willingness to pay for PHR showed significantly higher demand for all the functions (p<0.01). For all the PHR service functions, those with willingness to pay for PHR service showed relatively higher demand than those with willingness to use PHR.

This study confirmed that 59.8% of healthcare consumers have willingness to use PHR, showing high demand for PHR in Korea. According to research by Markle Foundation, around 60% of American adults in 2005 and around 46.5% in 2008 had willingness to use PHR online, showing demand for PHR similar to that in Korea21)22). Willingness to use PHR was higher in older people, those with high income, those with a disease, and those with experience to use health information on the Internet. Contrary to our expectation, however, willingness to use PHR was not statistically significantly different according to the presence of disease in family and the awareness of PHR. Of the healthcare consumers, only 8.5% knew about PHR, showing quite low awareness of PHR in Korea. In its research, HIMSS Foundation reported that 51% of healthcare consumers mentioned their unawareness of PHR as a reason for not using PHR and this suggests that the awareness of PHR is low also in the U.S.20). This study did not observe any significant difference in willingness to use PHR according to the awareness of PHR, but as demonstrated by research in the U.S., the low awareness of PHR may affect the use of PHR, so efforts should be made to enhance people's awareness of PHR. As willingness to use PHR is higher in old age groups, it is necessary to provide customized services according to each age group's requirements. Moreover, support is required for old people unfamiliar with online services so that they can use PHR through education or with the help of their family or agent. For those with a disease, it is important to help them know and manage their disease properly by providing individualized disease managements or online community services.

Factors affecting healthcare consumers' willingness to use PHR were income, education level, and experience to use health information on the Internet. Willingness to use PHR was around 4.6 times higher in middle school graduates than in elementary school graduates, 13.5 times and 3 times higher, respectively, in those with average monthly household income of over 6,000,000 won and those with 4,500,000-6,000,000 won than in those with below 1,500,000 won, and 1.96 times higher in those with experience to use health information on the Internet than in those without.

In the subjects of this study, the percentage of those with willingness to pay fee for PHR was 27.8%, not a low level. According to a survey by Harris Interactive, 37% of American adults in 2002 and 36% in 2005 had willingness to pay fee for online communication with healthcare providers24)25), and Adler et al. reported that 28% of patients were willing to pay fee for online communication with healthcare providers, 17% for the view of health records, 9% for the refill of drug prescription, and 5% for online appointment, and 59% of the respondents were willing to pay for at least one of services26). If the participants of this study were surveyed on their willingness to pay for each function of PHR systems as in the research of Adler et al., they would have shown much higher willingness to pay than this result. Willingness to pay for PHR service was affected by income. That is, it was 5.9 times higher in those with average monthly household income of 4,500,000-6,000,000 won than in those with below 1,500,000 won. Both willingness to use PHR and willingness to pay for PHR service were affected by income. The higher income is, the higher accessibility to PHR is likely to be, so it is important to prepare measures for this matter.

Healthcare consumers expected that the use of PHR would have a high economic effect in terms of time and cost for healthcare providers and consumers. This suggests that when PHR is introduced it will be broadly accepted by healthcare consumers.

Healthcare consumers showed high demand for all the health record items and PHR service functions presented in this study, and the demand was particularly high in those with willingness to use PHR and willingness to pay for PHR service. Among health records, surgical history and test results were highly demanded, and this is consistent with Kim Jin-hyeon's report that demand was highest for test results (including the results of general tests and radiographic examination)23). Among PHR service functions, 'Manage Patient Originated Data' was most highly required, and those with willingness to pay for PHR service showed high demand for 'Health Education' and 'Online Encounter Reservation.' In the research of Markle Foundation, American people showed high preference for functions related to communication with healthcare providers such as 'Send email to the doctor' (75% of the respondents) and 'Transmit records to specialists' (65%)9). Among Korean healthcare consumers also, those with willingness to use PHR and those with willingness to pay for PHR service showed high preference for 'Communications Between Provider and Patient' (4.25 and 4.36, respectively).

The results of this study showed that healthcare consumers have high demand for PHR, and although it is not recognized and used widely yet, PHR is an essential service. In the nationwide introduction of PHR in the future, in order to enhance people's awareness of PHR and improve equality in the distribution of resources for vulnerable classes, efforts should be made to execute campaigns and education for people, to ease accessibility to the service, and to reduce gap in service utilization skills. Particularly because it is highly likely that PHR will be provided online through the PHR system4)9) it is desirable to educate people on the Internet and information technology. According to research by HIMSS, healthcare providers' recommendation was the most useful method of encouraging Americans to use PHR20). Accordingly, it is considered important to educate healthcare providers on PHR service and its campaign so that they have clear understanding of PHR and reeducate healthcare consumers. Furthermore, in building PHR services in the future, it will be helpful to refer to healthcare consumers' requirements for health records and functions presented in this study.

This study is the first attempt to survey Korean healthcare consumers on their willingness to use PHR and their awareness of PHR, and their requirements for health records and PHR service functions. Moreover, this study is distinguished from previous research in Korea and other countries in that it organized requirements for data and functions through reviewing related literature and case studies based on PHR-System Functional Model, Release 1 in HL7.

This study has limitations as follows. Available previous research was not sufficient due to the market situation that PHR service is not popular in Korea and other countries yet. Thus, we had difficulty in finding previous studies comparable with our study. Because the questionnaire survey was conducted locally using a sample obtained through quota sampling, which is a non-probability sampling method, there is the possibility of sampling bias27). Nevertheless, we made efforts to improve the quality of data by increasing respondents' sincerely in answering and their understanding of the questions through one-to-one individual interviews by trained interviewers.

Figures and Tables

V. Acknowledgement

This study was conducted with the support of the Healthcare Technology Promotion Project of the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Task Number: A050909).

References

1. Kim YS. Lifetime health maintenance program for Korean. J Korea Assoc Health Promot. 2004. 2(2):99–116.

3. Eysenbach G. Consumer health informatics. BMJ. 2000. 320(7251):1713–1716.

4. Ball MJ, Smith C, Bakalar RS. Personal health records: empowering consumers. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2007. 21(1):76–86.

7. Endsley S, Kibbe DC, Linares A, Colorafi K. An introduction to personal health records. Fam Pract Manag. 2006. 05. 13(5):57–62.

8. Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, Overhage JM, Sands JZ. Personal health records: definition, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006. 13(2):121–126.

9. A public-private collaboration. the personal health working group final report. Markle Foundation. 2009. Retrieved July 31. Available at: http://www.markle.org/downloadable_assets/final_phwg_report1.pdf.

10. AHIMA e-HIM Personal Health Record Work Group. The Role of the Personal Health Record in the EHR. J AHIMA. 2005. 76(7):64A–64D.

11. HIMSS. Personal Health Records Definition and Position Statement. The Personal Health Record Steering Committee Report. 2007. 09. 28.

12. NAHIT. Defining Key health Information Technology Terms. The National Alliance for Health Information Technology Report. 2008. 04. 28.

13. Tang PC, Lansky D. The missing link: bridging the patient-provider health information gap. Health Affairs. 2005. 24(5):1290–1295.

14. Halamka JD, Mandl KD, Tang PC. Early experiences with personal health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008. 15(1):1–7.

15. NIA. Informatization White Paper. The National Information Society Agency of Korea Final Report. 2008.

16. NIDA. Survey on the Computer and Internet Usage. The National Internet Development Agency of Korea Final Report. 2008. 02.

17. NIDA. Survey on the Internet Usage. The National Internet Development Agency of Korea Final Report. 2008. 11.

18. HL7. PHR-System Functional Model, Release 1. Draft Standard for Trial Use. 2008. 11. The EHR Technical Committee.

19. NCVHS. Personal Health Records and Personal Health Record Systems. The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics Final Report. 2009. Retrieved July 31. Available at: http://www.ncvhs.hhs.gov/0602nhiirpt.pdf.

20. HIMSS. Personal Health Records. HIMSS Vantage Point July 2006;4(1):1. 2009. Retrieved July 31. Available at: http://www.himss.org/content/files/vantagepoint/pdf/vantagepoint_0706.pdf.

21. Attitudes of Americans regarding personal health records and nationwide electronic health information exchange. Key findings from two surveys of Americans conducted by Public Opinion Strategies, Alexandria, Va. Markle Foundation. 2009. Retrieved July 31. Available at: http://www.connectingforhealth.org/resources/101105_survey_summary.pdf.

22. Americans Overwhelmingly Believe Electronic PHR Could Improve Their Health. Markle Foundation. 2009. Retrieved July 31. Available at: http://www.connectingforhealth.org/resources/ResearchBrief-200806.pdf.

23. Kim JH. Needs for healthcare consumer related Informatization in Healthcare Sector. Korea Health Industry Development Institute Final Report. 2006. 06.

24. Taylor H, Leitman R, editors. Patient/physician online communication: many patients want it, would pay for it, and it would influence their choice doctors and health plans. Harris Interactive Health Care News. 2002;2(8):1-3. 2009. Retrieved July 31. Available at: http://www.harrisinteractive.com/news/newsletters/healthnews/HI_HealthCareNews2002Vol2_Iss08.pdf.

25. Gullo K, editor. Many Nationwide Believe in the Potential Benefits of Electronic Medical Records and are Interested in Online Communications with Physicians. Harris Interactive Health Care News. 2005;4(4):1-5. 2009. Retrieved July 31. Available at: http://harrisinteractive.com/news/newsletters/wsjhealthnews/WSJOnline_HI_Health-CarePoll2005vol4_iss04.pdf.

26. Adler KG. Web portals in primary care: an evaluation of patient readiness and willingness to pay for online services. J Med Internet Res. 2006. 8(4):e26.

27. Cho SK, Kim JY, Na YJ, Lee MJ. How to Improve the Electoral Polls?: the case of the 2006 local elections. J Korean Assoc Survey Res. 2007. 8(1):31–54.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download