Case Report

A 70-year-old man was referred to our hospital for severe pain, swelling, and pus discharge in his right elbow. Twenty five days prior to admission, he had fallen and injured his right elbow, with a puncture of the elbow with a tear three centimeters long. Five days later, he underwent incision and drainage of his right elbow for an infected abscess at a private clinic. However, despite treatment, the pain and swelling showed rapid progression.

His medical history was remarkable for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus for twenty years. He had smoked ten cigarettes daily for 40 years. He denied a history of drug abuse and had not undergone any specific dental treatment.

At admission, his temperature was 36.6°C, blood pressure was 125/80 mmHg, pulse rate was 80 beats/min, and respiration rate 16 breaths/min. His mental status was alert. The wound on the right elbow had a laceration of three centimeters in size. The olecranon was exposed with signs of inflammation of the adjacent muscles with draining discharge (

Fig. 1).

| Figure 1The wound on the right elbow with three-centimeter of laceration and signs of inflammation.

|

His leukocyte count was 7,280/mm3, with 70% neutrophils, 20% lymphocytes, and 6% monocytes. Blood test showed C-reactive protein of 4.69 mg/dl (normal <0.5 mg/dl), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 65 mm/h, a high glucose level of 231 mg/dl, aspartate transaminase of 26 U/L and alanine transaminase of 36 U/L. Glucosuria was also noted in the urine analysis and HbA1c was 9.8%.

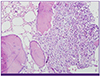

Magnetic resonance imaging showed osteomyelitis of olecranon and myoabscess (

Fig. 2A and B). Empirical ceftriaxone (2 g q24h) and metronidazole (500 mg q8h) were administered intravenously. The patient underwent surgical interventions consisting of debridement of affected bone and partial bone resection on the first hospital day.

| Figure 2(A) MRI T2 coronal slide of the epicondyle showing partial tear of the distal triceps tendon, from olecranon insertional portion to 5 cm above. (B) MRI T2 axial slide (enhanced). Complicated hematoma with myositis and cellulites is also noted (arrow).

|

Pus from the excised medial and deep triceps tissue biopsy specimens yielded A. meyeri and Peptoniphilus asaccharolyticus using a VITEK II ANC card (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

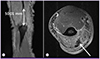

Histological examination of the biopsy specimen revealed inflammatory cellular infiltration with abscess formation, but no colonies of sulfur granules were observed, even with repeated examination by pathologists (

Fig. 3).

| Figure 3Abscess is noted, mostly composed of neutrophils. Abscess surrounds mature bone fragments. (Hematoxylin and eosin stain, x200)

|

The patient’s antibiotic regimen was switched to oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (500 mg/125 mg q8h for seven months) and he was discharged home with ambulation on hospital day 29.

After a follow-up period of seven months, there were no clinical signs or symptoms of recurrence.

Discussion

Actinomyces spp. normally colonize the mouth, colon and vagina [

2] and usually cause osteomyelitis of head and neck [

3]. The most commonly infected body regions are cervicofacial (55%), abdominopelvic (20%) and pulmonothoracic (15%) [

45]. Involvement of other parts of the body is uncommon, and because of the exclusively endogenous habitat of the bacteria, actinomycosis of an extremity is very rare [

6]. One percent of reported case of anaerobic osteomyelitis had

Actinomyces spp. [

4]. To the best of our knowledge, among 15 English-language reports of long bone osteomyelitis of the extremity, only one case of primary upper extremity actinomycotic osteomyelitis was reported in 1954 [

7]. This is the first case of olecranon osteomyelitis due to

A. meyeri in Korea.

The source of actinomycotic organisms and the mechanism whereby the bacteria are transmitted to the site of infection in cases involving a long bone are usually unclear [

2]. However, most of the long bone osteomyelitis due to

A. meyeri occurred after traumatic injury which creates an anaerobic environment predisposing to this bacterial growth [

6]. In this case reported here, the patient did not have oral cavity injury nor did have poor dental hygiene. There was no evidence of other organs involvement, which can cause disseminated infection, either. Although environmental sources have been implicated on rare cases [

8], it is presumed that possible routes of infection is piercing trauma from an environmental source.

A combination of appropriate microbiologic, molecular and pathologic studies would maximize the chances of successful diagnosis of actinomycosis [

24]. Half of the primary actinomycosis cases were diagnosed clinicopathologically, and in the remaining cases

, Actinomyces spp. were grown from culture specimens [

7]. Thus, actinomycosis should not be excluded even though the characteristic pathologic findings are not present, though the single most helpful diagnostic clue for actinomycosis is presentation of sulfur granules in the specimens [

2]. One case of pulmonary actinomycosis has been reported in which pleural biopsy tissue showed only reactive fibroblastic tissue with fibrin and acute inflammation, but the specimens grew actinomycosis [

9]. Our patient had an olecranon osteomyelitis due to

A. meyeri with

P. asaccharolyticus, which was identified by VITEK II, not by sulfur granules in multiple sections. As a result of fibrosis with or without inflammation, sulfur granules are easily missed in the histologic sections of a surgical specimen [

2].

Identification of

Actinomyces spp. is difficult. Commonly, identification in clinical laboratories is based upon a limited range of conventional biochemical test. Colonial morphology and gas-liquid chromatography can be used. Recent advances in microbiologic identification technique, 16s rRNA gene amplification is known to increase the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis [

291011]. In this case, however, further evaluation was not possible because specimen was discarded after identification by VITEK II card.

In review of 203 case reports in Korea, tissue cultures were performed in only 6.9% (14 cases among 203). Most cases of actinomycosis (93%, 189 cases among 203)were diagnosed only histopathologically. We found two actinomycosis cases diagnosed only by tissue culture, meaning that the actinomycosis might have been underestimated or neglected by diagnostic maneuver. For successful diagnosis of actinomycosis, not only pathologic studies, but also microbiologic studies should be performed.

It is interesting that other bacteria have been cultured together, called companion microbes and these bacteria may serve as copathogens by aiding in the inhibition of host defenses or by reducing oxygen tension [

212]. Companion anaerobic bacteria facilitate

Actinomyces spp. infection by establishing a microaerophillic environment [

13].

Peptoniphilus, companion microbes, Gram-positive anaerobic cocci, originally classified in the genus

Peptostreptococcus, is a part of the normal microflora in human beings and animals.

Peptoniphilus spp

. are usually associated with opportunistic human infections [

14]. Although studies of Gram-positive anaerobic cocci have been limited due to the lack of a valid identification scheme, recently they are increasingly recognized as important pathogens [

14].

Treatment of osteomyelitis due to

Actinomyces spp. requires prolonged use of antibiotics with β-lactam ring such as high dose penicillin or amoxicillin [

15]. Tetracycline, erythromycin and clarithromycin are effective alternatives [

16]. Surgical intervention should be considered in some complicated cases [

15]. The duration of antibiotic therapy is debated and individualized, intravenous penicillin for two to six weeks, followed by oral therapy with penicillin or amoxicillin for six to twelve months, is a reasonable guideline for serious infections [

2]. Our patient was treated successfully with three weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone and a seven month course of oral amoxicillin.

In this case report, we present the first case of olecranon osteomyelitis due to A. Meyeri with P. asaccharolyticus with an emphasis on the diagnostic maneuver of actinomycosis. Traditionally, actinomycotic infection was considered, when the typical pathologic findings were present. However, bacteriologic identification is as necessary as pathologic findings to prevent treatment failure of actinomycosis infection.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download