Abstract

Roseomonas are a gram-negative bacteria species that have been isolated from environmental sources. Human Roseomonas infections typically occur in immunocompromised patients, most commonly as catheter-related bloodstream infections. However, Roseomonas infections are rarely reported in immunocompetent hosts. We report what we believe to be the first case in Korea of infectious spondylitis with bacteremia due to Roseomonas mucosa in an immunocompetent patient who had undergone vertebroplasty for compression fractures of his thoracic and lumbar spine.

Roseomonas species are slow-growing, gram-negative bacteria that have been isolated from environmental sources including air, water, and soil [1]. Human infections caused by Roseomonas spp. are infrequently reported and typically manifest in immunocompromised patients as catheter-related bloodstream infections, urinary and respiratory tract infections, peritonitis, gastroenteritis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, wound and soft tissue infections, eye infections, and ventriculitis [2345]. However, Roseomonas infections have rarely been reported in immunocompetent hosts because of their low pathogenic potential in humans. However, some reported infections were related to surgery [34]. We report what we believe to be the first case in Korea of infectious spondylitis with bacteremia due to Roseomonas mucosa in an immunocompetent patient who had undergone vertebroplasty for compression fractures.

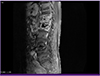

A 74-year-old man was admitted for back pain of that had persisted for six months. He had undergone vertebroplasty for compression fractures of his thoracic (T) 11, T12, and lumbar (L) spine 1 bodies 16 months prior, and subsequent laminectomy was performed for spinal stenosis on L3-4 and L4-5. His back pain was somewhat relieved. Starting two months prior, however, he had increased back pain accompanied by a tingling sensation in both feet and toes. One week before admission, he had undergone an L-spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan at another hospital and was transferred to our hospital for suspected infectious spondylitis at his T-L spine. His temperature and vital signs were normal. There was severe tenderness on his T11-L1 vertebral and paravertebral areas, but no erythema, swelling, or local heat. The motor and sensory functions of both legs were normal, and his deep tendon reflexes were also normal. Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 5,540/mm3, platelet level of 549,000/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 40 mm/h, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 24 mg/L. The results of urinalysis, plasma electrolytes, and kidney and liver function tests were all within normal ranges. A scanning MRI of the L-spine showed a paravertebral inflammatory mass and abscess from vertebrae T11 to L1 (Fig. 1) compatible with infectious spondylitis.

On the third day after admission, both sets of blood cultures taken upon admission were positive for gram-negative bacilli. On the fourth day after admission, a bone biopsy from the T11 body was cultured for bacteria, fungus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and the patient was empirically treated with intravenous cefazolin. On the eighth day, Roseomonas gilardii was isolated from both blood cultures taken on admission using the Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux, Durham, NC, USA). We performed 16S-rDNA gene sequence analysis to confirm the molecular identification of the blood isolate, and the bacterial isolate was identified as Roseomonas mucosa (99% similarity). Pathological examination of the T11 spine biopsy specimen showed inflammatory cells and mild fibrosis in the infected bone tissue; however, the bone tissue culture was negative. R. gilardii isolated from blood the culture was therefore considered the causative pathogen of infectious spondylitis in this case. Based on antibiotic susceptibility testing results using the Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux), we changed the empirical antibiotic treatment to a specific ceftazidime treatment on the eighth day after admission. After hospitalization, his back pain improved. However, the tingling sensation in both feet and toes persisted. Because of spinal instability due to severe bony destruction in the T-L spine and poor clinical response to antibiotic therapy, we recommended surgical treatment, but the patient refused the operation and requested hospital discharge. He left our hospital after taking antibiotics for two weeks, and was lost to follow-up.

One month later, he revisited our clinic because of worsening of his back pain. The ESR and CRP were 38 mm/h and 46 mg/L, respectively. An L-spine MRI scan showed that the bilateral psoas abscesses on T11 to L1 vertebrae had increased in size. The patient underwent total corpectomy and no bacterial isolates were cultured from specimens obtained during the surgery. The patient was treated with a six-week course of intravenous ceftazidime. The ESR and CRP levels normalized and his back pain was much improved at discharge.

Roseomonas was first described in 1993 and is currently classified into 15 subspecies, including R. gilardii, R. cervicalis, R. mucosa, R. aerialata, R. aquatica, R. lacus, R. terrae, R. stagni, R. vinacea, and three unnamed species (genospecies 4, 5, and 6) [56]. Initially, R. mucosa and R. gilardii subspecies rosea were grouped with R. gilardii, but R. mucosa was reestablished as a distinct species from R. gilardii due to sufficient phylogenic and phenotypic differences [78]. However, R. mucosa is difficult to differentiate from R. gilardii due to lack of clinical expertise and commercially available kits. Commercial microbiologic methods to discriminate between R. mucosa and R. gilardii are lacking and their 16S-rDNA have not been routinely sequenced for identification [8]. In our case, the causative organism was misidentified as R. gilardii by the commercial identification kit, but was confirmed as R. mucosa by 16S-rDNA gene sequence analysis.

Most Roseomonas infections have been reported in patients with immunocompromised conditions and diseases, such as immunosuppressive or steroid therapy, liver cirrhosis, end stage renal disease, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, and organ transplantation [5]. Primary bacteremia, cellulitis, and surgical site infections caused by Roseomonas have been rarely reported in immunocompetent hosts [57]. There have been several reports of Roseomonas infections after surgery in immunocompetent patients: R. gilardii septic arthritis after surgery for a sports-related right anterior cruciate ligament injury [4], R. gilardii surgical site infection after cranioplasty [9], and R. mucosa spinal epidural abscess following instrumented spinal fusion surgery [10]. The patient in our case was also an elderly person who had undergone vertebroplasty for compression fractures.

Even though the time interval between vertebroplasty and Roseomonas infectious spondylitis was too long to consider it a causative relationship, we presumed that the previous vertebroplasty might have been a precipitating factor for infectious spondylitis in our case. This reasoning was supported by previous reports that invasive interventions could be a precipitating factor for bone and soft tissue infections due to Roseomonas spp. [910].

Roseomonas is usually resistant to penicillins such as ampicillin, ticarcillin, and piperacillin, but is susceptible to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, and tetracycline [5]. Our isolate was resistant to ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and piperacillin, but was susceptible to carbapenems, ceftazidime, ticarcillin, and tobramycin.

To our knowledge, this is the first report in Korea of infectious spondylitis due to R. mucosa in an immunocompetent patient. Clinicians should be aware of this unusual infection even in immunocompetent patients.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Wallace PL, Hollis DG, Weaver RE, Moss CW. Biochemical and chemical characterization of pink-pigmented oxidative bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1990; 28:689–693.

2. Bibashi E, Sofianou D, Kontopoulou K, Mitsopoulos E, Kokolina E. Peritonitis due to Roseomonas fauriae in a patient undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000; 38:456–457.

3. Nahass RG, Wisneski R, Herman DJ, Hirsh E, Goldblatt K. Vertebral osteomyelitis due to Roseomonas species: case report and review of the evaluation of vertebral osteomyelitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995; 21:1474–1476.

4. Fanella S, Schantz D, Karlowsky J, Rubinstein E. Septic arthritis due to Roseomonas gilardii in an immunocompetent adolescent. J Med Microbiol. 2009; 58:1514–1516.

5. Wang CM, Lai CC, Tan CK, Huang YC, Chung KP, Lee MR, Hwang KP, Hsueh PR. Clinical characteristics of infections caused by Roseomonas species and antimicrobial susceptibilities of the isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012; 72:199–203.

6. Rihs JD, Brenner DJ, Weaver RE, Steigerwalt AG, Hollis DG, Yu VL. Roseomonas, a new genus associated with bacteremia and other human infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1993; 31:3275–3283.

7. Dé I, Rolston KV, Han XY. Clinical significance of Roseomonas species isolated from catheter and blood samples: analysis of 36 cases in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 38:1579–1584.

8. Han XY, Pham AS, Tarrand JJ, Rolston KV, Helsel LO, Levett PN. Bacteriologic characterization of 36 strains of Roseomonas species and proposal of Roseomonas mucosa sp nov and Roseomonas gilardii subsp rosea subsp nov. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003; 120:256–264.

9. Ece G, Ruksen M, Akay A. Case report: cranioplasty infection due to Roseomonas gilardii at a university hospital in turkey. Pan Afr Med J. 2013; 14:162.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download