Abstract

Background

It is unclear to which extent the rate of disclosure of the diagnosis "HIV" to the social environment and the nature of experienced responses are correlated with the current mental health status of HIV-infected patients living in Germany.

Materials and Methods

Eighty consecutive patients of two German HIV outpatient clinics were enrolled. Patients performed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in its German version. Disclosure behaviour and the experienced responses after disclosing as perceived by the participants were assessed using a questionnaire. In addition, patients were asked to state whether they felt guilty for the infection on a 1-4 point Likert scale.

Results

Pathological results on the anxiety scale were reached by 40% of male and 73% of female patients, and on the depression scale by 30% of male and 47% of female patients, thus significantly exceeding recently assessed values in the German general population, except for depression in males. None of the HADS scale results was interrelated either with the rate of disclosure or the experienced responses. 36% of patients reported to feel guilty for the infection, which was positively correlated with results from the HADS. Limitation: The time since the single disclosure events was not assessed, and the subgroup of women was comparably small.

Conclusions

Despite substantial improvement in treatment, HIV-infected patients in Germany still suffer from an elevated level of anxiety and, in part, depression. However, mental health status was neither related with disclosure behaviour nor with experienced responses. We hypothesize that internal beliefs may play a more important role.

The availability of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) since the late 90s has dramatically changed the course of HIV (Human immunodeficiency virus) infection, and patients now can expect an excellent long-term prognosis [1]. Nevertheless, facing a chronic condition is an emotional challenge, and a cure for HIV is unlikely to become available at least in the next decade [2]. In addition, patients may experience restrictions in their sexual life [3], and are at risk to encounter disease-associated discrimination [4]. It is thus not surprising that the prevalence of mental disorders in HIV-infected patients was reported to be higher compared to the general population, especially in the subgroup of women [5, 6, 7].

Self-report questionnaires on psychopathological symptoms such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) are reliable instruments and easy to use. The HADS was conceptualized for outpatients with somatic diseases and focuses on mild to moderate psychopathologic symptoms, and comprises two subscales, anxiety and depression [8, 9]. Its results highly correlate with other self-report instruments and clinical judgment [10, 11]. Recent representative data for the general German population are available [12].

Disclosure of the disease status to others may substantially contribute to a successful coping process [13], since concealment of personal distressing information was shown to be negatively associated with emotional well-being [14], and a higher number of disclosures may result in an increase of social support [15]. The decision to disclose may be influenced by pre-existing personal traits, with anxious persons being more likely to avoid to inform others [16] since disclosure can also result in significant discrimination. Beside perceived and experienced/enacted stigma, patients may also suffer from internalized stigma, associated with the feeling of being guilty for the infection [17].

It is the aim of the current study to investigate whether the rate of disclosure to persons in the social environment and the nature of the encountered reactions as assessed by a questionnaire are interrelated with anxiety or depression as assessed by the HADS in a sample of HIV patients living in Germany. We assumed "feelings of guilt" to be an additional intervening variable between the diagnosis and emotional well-being.

The current investigation uses data of a recently published study [18]. We investigated a consecutive sample of HIV-infected patients who came for routine visits to the Department of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology at Hanover Medical School, and to the Ist Medical Department of the University Hospital, Mainz, both located in Germany. The centres are of medium size (Hanover: ca. 450, Mainz: ca. 300 patients in continuous care, respectively). Although both clinics are associated with academic institutions, they are open for all HIV-infected patients of the region. We included only patients who had received their diagnosis 1-6 years ago in order to allow sufficient time for coping, but still adequate recall. Further inclusion criteria were age older than 18 years and sufficient literacy. Patients were asked to participate by the attending physician. After giving informed consent patients at the same visit in a separate room filled in a questionnaire on disclosure behaviour which consisted of a list of predefined 36 (plus 10 optional) persons who may play a role in the patient's social environment. Primarily, patients were asked whether the respective person was present in their social environment. Secondly, patients had to mark whether they had disclosed their disease to this specific person. In a third step, the reaction of the informed person as perceived by the patient was rated on a 1 to 4 point Likert scales , differentiated into an immediate reaction ("This person has reacted - rejecting / taking distance" up to "- very kindly") and a long term reaction ("In the subsequent time this person has been -treating me very badly" up to "-very supportive"). On each of these Likert scales, 1 or 2 points were valuated as a negative, and 3 or 4 points as a positive response. At the same time point, HIV-infected patients completed the German version of the HADS [19]. It comprises 14 items with four pre-specified answers. On each scale, one missing answer is tolerated and substituted by the average result of the other items. A score ≥ 8 on a single scale or ≥ 13 in the whole HADS are considered as pathological [12]. In addition, patients were asked to rate the statement "I feel guilty because I am HIV positive" by completing a 1-4 point Likert scale from "never" up to "very often".

The study was approved by the Ethics committees of Hanover Medical School, Lower Saxony (No. 4437) and the Landesärztekammer Rhineland-Palatinate (No. 837.187.08).

The main hypothesis was tested by using correlation analyses. Because of the skewed distribution of the disclosure variables ('percentage of informed persons': skewness: -1.2; ZKolmogorov-Smirnov: P < 0.001), Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was chosen.

Mean and standard deviations (SD) and frequency were used for continuous and categorical data.

In order to compare mean HADS scores between the HIV patient sample and controls from a current publication providing mean (SD) [12], we assumed mean (SD) values for the HADS-A-scale of at least 9.0 (± 4.3) for bodily ill patients [20], and for the HADS-D-score of at least 6.5 (4.4) like in comparable studies [20, 21, 22]. Power computations were conducted using PASS 2008 power module [23]. Based on an intended power of 80% and a Bonferroni-corrected (4 trials) significance level of 0.013, 75 cases were calculated to be necessary to detect expected mean differences of a 1.7 point HADS-D raw score difference between bodily ill patients and controls [12] as the smallest difference of both.

Raw values of the HADS were computed based on the regression model according to Hinz and Brähler [12] with respect to age and gender and were compared by Wilcoxon test. The chi-square-test was used to analyse differences in the frequency of patients exceeding cut-off scores. All P-values were two-tailed and of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data analysis was done using SPSS (Release 19.0.0.1, IBM, New York, NY, USA).

Patients' baseline data, rate of disclosure and support experiences in detail are published elsewhere [18]. In short, between February and October 2007, 85 HIV-infected patients have been asked, and 83 participated (response rate 98%) but three patients did not complete the HADS, thus data from 80 (65 male and 15 female) patients were available for analysis. The mean age (SD) of these patients was 43 (10) years. 81% of patients were male, and 91% were born in Germany. 70 % received antiretroviral treatment. The mean (SD) time since diagnosis was 3.5 (1.6) years. All patients were outpatients and did not suffer from any acute opportunistic infection. The source of infection as stated by the patients were homosexual contacts in 41%, heterosexual contacts in 36% (including 6% of patients having migrated from areas with high prevalence, i.e. South East Asia or Subsaharian Africa), intravenous drug use in 4%, and it was unknown in 19%. On average, patients reported of a social environment of 14.5 (7.7) persons, and had informed 59% (32) of them about their disease. After 80% (26) of the disclosures, HIV-infected patients experienced a supportive reaction, and a long-term support from 81% (25) of persons they had disclosed to.

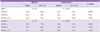

Raw values of patients in comparison to persons with corresponding age and gender of the general German population [12] are shown in table 1. When applying the common cut-off score of ≥ 8 to the data, 40% of HIV-infected male patients reached or exceeded this value in the anxiety subscale, compared to 18% in the male general population (P < 0.001). In women, this difference was even higher with 73 versus 23% (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Concerning the depression subscale, no significant difference in the proportion of cases scoring equal or above 8 was seen between male patients and the male general population (30 vs. 24%) (P = 0.20) but the difference, again, was higher for female patients (47 versus 24%) (P = 0.036). The proportion of subjects with a total HADS score ≥ 13 was higher in both HIV-infected men and women compared to the general population (P = 0.017, 0.003, resp.).

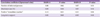

We did not find an interrelation neither between the number of disclosures nor the disclosure rate with either of the HADS scale results (Table 3). Interestingly, this was also true for the responses as experienced by the patients after disclosure, both "immediate response", and "long-term support".

We categorized patients in groups of low disclosure (0-2 persons), medium (3-10 persons), and high disclosure pattern (> 10 persons), respectively, in order to investigate whether disclosure frequency would correlate with the HADS results, but this was not the case (data not shown).

Since the infection with HIV had become a manageable but chronic disease, mental health had entered into the focus of medical care. Emotional well-being not only has a major impact on the individual's quality of life, but is essential for maintaining high rates of compliance which remains the Achilles' heel of ART [24].

This study was performed in Germany, a country with a low (0.09%) but continuously increasing HIV prevalence (ca. 3,000 new infections per year). Homosexually infected patients form the majority (ca. 65.4%), followed by heterosexual transmissions (ca. 21.8%), and the infection rate via intravenous drug use is comparably low (ca. 10.8% of patients) [25]. Using the well-established HADS, our data suggest that patients still suffer from an increased level of anxiety, and, to a lesser extent, depression. Interestingly, available data from the pre-ART era in a French-Canadian HIV patient cohort are quite comparable to our results with mean results on the anxiety scale of 7.48 ± 4.2 points, and on the depression scale of 4.37 ± 3.7 points [26], despite the fact that life expectancy was much worse at that time. A recent study across Western Europe and Canada found that 33% of patients had a pathological anxiety score of more than 8 points and 16% had an elevated depression score which is lower in comparison to our results [27].

In our study, no correlation of the rate of disclosure with the HADS results could be found, and, even more surprising, the nature of how participants experienced responses from others after disclosing did not correlate with the HADS. This contradicts the hypothesis that a higher disclosure rate may be beneficial for successful coping and that social support will decrease the likelihood of depressive symptoms, as well as the assumption that persons with a lower rate of anxiety and depression would be more likely to disclose. The literature is ambiguous in these aspects: A positive effect of disclosure was seen [28], while others found that high rates of disclosure cause even more distress and stigmatization [29]. Only disclosure to family members was weakly associated with less depression [30, 31]. In a meta-analysis of 21 studies, Smith et al. [32] found a positive, but heterogeneous correlation of disclosure and social support.

Disclosure and social support as well as the extent of psychological symptoms may substantially differ depending on the socio cultural background HIV-infected people are living in. In a global survey, Nachega et al. reported that Korean patients were least likely to disclose their disease status. Further on, patients from the Asia-Pacific region were most anxious to lose family and friends after disclosure in comparison to the global average [33].

36% of our patients rated to feel guilty in relation to their infection, and these results were highly correlated with the HADS scales. It can thus be speculated that internal beliefs have a stronger influence on anxiety and depression than the "real" experienced social feedback. Studies from other diseases suggest that the perception of discrimination does not necessarily require "real" negative experiences [34], and that "self-stigmatization" is followed by an increase in distress [35].

Anxiety may be considered normal response to significant illness. However, further factors may contribute to the increased rate of mental distress in HIV patients: Pre-existing psychological morbidity may increase the risk of HIV acquisition, e.g. via drug addiction or self-destructive high-risk sexual behaviour, but the extent of this effect is difficult to assess [5]. Additionally, in some cases, HIV may exert direct effects on the CNS, causing both neurocognitive disorders and depressive symptoms [36].

This study is limited by the fact that the data was assessed in a consecutive patient sample with a comparably small subgroup of women using self-report questionnaires rather than standardized interviews. In order to avoid overloading the questionnaires, we did not assess the exact time point of each disclosure event, thus our data do not allow to discriminate between short and long-term emotional effects of disclosure. The retrospective design inherits the possibility of a recall error. In addition, we did not collect data on education and socioeconomic status of the patients which as well can influence anxiety and depression. A long-term panel study is needed to dismantle the relationships between internal beliefs (like feelings of guilt), disclosure and psychological well-being in HIV-patients.

In conclusion, despite major progress in HIV treatment, patients living in Germany still suffer from an increased level of anxiety and, in part, depression. Interestingly, neither a higher rate of disclosure nor the nature of experienced reactions was associated with emotional well-being as assessed by the HADS. We speculate that the impact of internal beliefs on emotional health is stronger than external experiences. These information may be helpful to council patients newly diagnosed with HIV.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Mean raw values ± standard deviation of the HADS subscales in comparison to controls (German healthy population as assessed by Hinz & Brähler, 2011)

HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale; HADS-A, hospital anxiety and depression scale for anxiety; HADS-D, hospital anxiety and depression scale for depression.

aScores were computed based on the regression model according to Hinz & Brähler (2011) with respect to age and gender.

bWilcoxon test.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all participating patients and Dr. Yvonne Alt for her support in patient care.

This project was supported by Deutsche AIDS-Stiftung.

The authors have no competing interests to report.

References

1. Van Sighem AI, Gras LA, Reiss P, Brinkman K, de Wolf F. ATHENA national observational cohort study. Life expectancy of recently diagnosed asymptomatic HIV-infected patients approaches that of uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2010; 24:1527–1535.

2. Chun TW, Fauci AS. HIV Reservoirs: pathogenesis and obstacles to viral eradication and cure. AIDS. 2012; 26:1261–1268.

3. Bouhnik AD, Preau M, Schiltz MA, Obadia Y, Spire B. VESPA study group. Sexual difficulties in people living with HIV in France--results from a large representative sample of outpatients attending French hospitals (ANRSEN12-VESPA). AIDS Behav. 2008; 12:670–676.

4. Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, Szekeres G, Coates TJ. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: a review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008; 22:Suppl 2. S67–S79.

5. Angelino AF, Treisman GJ. Management of psychiatric disorders in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 33:847–856.

6. Kemppainen JK, Mackain S, Reyes D. Anxiety symptoms in HIV-infected individuals. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013; 24:1 Suppl. S29–S39.

7. Song JY, Lee JS, Seo YB, Kim IS, Noh JY, Baek JH, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ. Depression among HIV-infected patients in Korea: assessment of clinical significance and risk factors. Infect Chemother. 2013; 45:211–216.

8. Hinz A, Schwarz R. Anxiety and depression in the general population: normal values in the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2001; 51:193–200.

9. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 67:361–370.

10. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002; 52:69–77.

11. Cairns JA, Johnston KM. Assessing the severity of depressive illness. J Clin Psychol. 1992; 48:455–462.

12. Hinz A, Brähler E. Normative values for the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in the general German population. J Psychosom Res. 2011; 71:74–78.

13. Jia H, Uphold CR, Wu S, Reid K, Findley K, Duncan PW. Health-related quality of life among men with HIV infection: effects of social support, coping, and depression. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2004; 18:594–603.

14. Uysal A, Lin HL, Knee CR. The role of need satisfaction in self-concealment and well-being. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010; 36:187–199.

15. Woodward EN, Pantalone DW. The role of social support and negative affect in medication adherence for HIV-infected men who have sex with men. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012; 23:388–396.

16. Collins NL, Miller LC. Self-disclosure and liking: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 1994; 116:457–475.

17. Audet CM, McGowan CC, Wallston KA, Kipp AM. Relationship between HIV stigma and self-isolation among people living with HIV in Tennessee. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e69564.

18. Kittner JM, Brokamp F, Jäger B, Wulff W, Schwandt B, Jasinski J, Wedemeyer H, Schmidt RE, Schattenberg JM, Galle PR, Schuchmann M. Disclosure behaviour and experienced reactions in patients with HIV versus chronic viral hepatitis or diabetes mellitus in Germany. AIDS Care. 2013; 25:1259–1270.

19. Herrmann C, Buss U, Snaith RP. HADS-D, hospital anxiety and depression scale-deutsche version; Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung von Angst und Depressivitt in der somatischen Medizin. Testdokumentation und Handanweisung. Bern, Gttingen, Toronto, Seattle: Verlag Hans Huber;1995.

20. Arnold LM, Leon T, Whalen E, Barrett J. Relationships among pain and depressive and anxiety symptoms in clinical trials of pregabalin in fibromyalgia. Psychosomatics. 2010; 51:489–497.

21. Cohen M, Hoffman RG, Cromwell C, Schmeidler J, Ebrahim F, Carrera G, Endorf F, Alfonso CA, Jacobson JM. The prevalence of distress in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Psychosomatics. 2002; 43:10–15.

22. Hansson M, Chotai J, Nordstom A, Bodlund O. Comparison of two self-rating scales to detect depression. Br J Gen Pract. 2009; 59:e283–e288.

23. Hintze J. Power analysis & sample size (PASS) software 2008. Accessed 28 February 2013. Available at: http://www.ncss.com.

24. Nel A, Kagee A. Common mental health problems and antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS Care. 2011; 23:1360–1365.

25. Robert-Koch Institute. German Epidemiological Bulletin 11/2013 (No 45). Accessed 15 December 2013. Available at: http://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2013/Ausgaben/11_13.pdf;jsessionid=20538032501F6E683E6F2A45F0B234FE.2_cid372?__blob=publicationFile.

26. Savard J, Laberge B, Gauthier JG, Ivers H, Bergeron MG. Evaluating anxiety and depression in HIV-infected patients. J Pers Assess. 1998; 71:349–367.

27. Bayon C, Robertson K, de Alvaro C, Burogs A, Cabrero E, Esther N, et al. The prevalence of a positive screen for anxiety and/or depressive symptoms in HIV-1 infected patients across western Europe and Canada - The CRANium Study. In : Presented at the 2nd International HIV & Women; Bethesda, USA. 2012.

28. Hays RB, McKusick L, Pollack L, Hilliard R, Hoff C, Coates TJ. Disclosing HIV seropositivity to significant others. AIDS. 1993; 7:425–431.

29. Clark HJ, Lindner G, Armistead L, Austin BJ. Stigma, disclosure, and psychological functioning among HIV-infected and non-infected African-American women. Women Health. 2003; 38:57–71.

30. Kalichman SC, DiMarco M, Austin J, Luke W, DiFonzo K. Stress, social support, and HIV-status disclosure to family and friends among HIV-positive men and women. J Behav Med. 2003; 26:315–332.

31. Petrak JA, Doyle AM, Smith A, Skinner C, Hedge B. Factors associated with self-disclosure of HIV serostatus to significant others. Br J Health Psychol. 2001; 6:69–79.

32. Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one's HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008; 20:1266–1275.

33. Nachega JB, Morroni C, Zuniga JM, Sherer R, Beyrer C, Solomon S, Schechter M, Rockstroh J. HIV-Related stigma, isolation, discrimination, and serostatus disclosure: a global survey of 2035 HIV-infected adults. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2012; 11:172–178.

34. Schmid-Ott G, Kuensebeck HW, Jaeger B, Werfel T, Frahm K, Ruitman J, Kapp A, Lamprecht F. Validity study for the stigmatization experience in atopic dermatitis and psoriatic patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999; 79:443–447.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download