This article has been corrected. See "Erratum: Nocardia Brain Abscess in an Immunocompetent Patient" in Volume 47 on page 304.

Abstract

Nocardia cerebral abscess is rare, constituting approximately 1-2% of all cerebral abscesses. Mortality for a cerebral abscess of Nocardia is three times higher than that of other bacterial cerebral abscesses, therefore, early diagnosis and therapy is important. Nocardia cerebral abscess is generally occur among immunocompromised patients, and critical infection in immunocompetent patients is extremely rare. We report on a case of a brain abscess by Nocardia farcinica in an immunocompetent patient who received treatment with surgery and antibiotics. This is the second case of a brain abscess caused by N. farcinica in an immunocompetent patient in Korea.

Nocardia species are gram-positive, aerobic, branching filamentous bacteria belonging to Actinomycetales. Nocardia asteroides and Nocardia farcinica are the most frequent pathogen. Although infection commonly occurs through inhalation or direct cutaneous inoculation, Nocardia species can spread to the central nervous system hematogenously, usually in immunocompromised patients [1, 2]. Nocardia brain abscess in an immunocompetent patient has rarely been reported [3]. In Korea, only one case of Nocardia brain abscess in an immunocompetent host has been reported [4]. We report an immunocompetent patient who had a Nocardia brain abscess, which was treated by stereotactic aspiration of the abscess and systemic antibiotics. This is the second case of a brain abscess caused by N. farcinica in an immunocompetent patient in Korea.

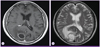

A 71-year-old male was admitted due to headache, dizziness, and nausea for three days. He was healthy, except that he had been diagnosed with hypertension two years before. His past medical history was unremarkable. His social history included intermittent alcohol consumption without smoking. The initial vital signs revealed blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg, heart rate of 76 beats per minute, respiration rate of 18 breaths per minute and body temperature of 36.9℃. He was alert upon admission. Physical examination revealed clear lung sound without rale or wheezing. The heart beat was regular without any murmur. There was no tenderness or rebound tenderness in the abdomen. Findings from other physical and neurological examinations were normal. There were no other symptoms such as fever, neck stiffness, photophobia, papilledema or other abnormalities. The initial peripheral blood count showed a white blood cell count of 11,200/mm3 (neutrophils 64.6%, lymphocytes 24.5%, monocytes 6.8%), hemoglobin level of 13.0 g/dL, platelet count of 211,000/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 38 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein level of 1.11 mg/dL. Blood chemistry showed a total protein level of 7.6 g/dL, albumin level of 4.3 g/dL, total bilirubin level of 0.9 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase 27/16 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 77 IU/L, BUN/Cr 9.2/0.8 mg/dL, Na/K 136/3.8 mEq/L, and Ca/P 9.0/4.7 mg/dL. Result of urinalysis was normal. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C antibody were all negative. Chest and abdomen radiographs were normal. Brain CT scan and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging showed multiple rim enhancing lesions with surrounding edema, which was presumed to be a brain abscess (Fig. 1).

After admission, the patient underwent a craniotomy with stereotactic aspiration of the abscess. During the operation, yellowish and turbid pus was aspirated and a cerebral abscess was diagnosed. Empirical parenteral antibiotics were started with ceftriaxone 2 g bid and metronidazole 500 mg tid. Gram stain of the pus showed beaded branching gram-positive bacilli. Urease test, esculin hydrolysis test, citrate test, and modified acid-fast stain using 1% acid alcohol were all positive and the bacteria grew at 42℃. Nocardia species were suggested by colonial morphology, Gram-stain, and modified acid fast bacillus (AFB) stain (Fig. 2). By manual, culture was identified as Nocardia species. For the accurate identification of Nocardia species, 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene-based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequencing was carried out. Primers of 27F (5'-AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG-3') and 1492R (5'-TAC GGY TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3') were used for 16S rRNA gene amplification. Size of 1466 bp 16S rRNA gene amplification sequencing was carried out by Solgent (Solgent Co, Daejeon, Korea) company which uses Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit and ABI PRISM 3730 DNA analyzer (PE Applied Biosystem, Foster, CA, USA). It showed 100% concordance to N. farcinica (GenBank accession number: KC478309) by BLAST Similarity Searching in GenBank. The organism was susceptible to amikacin, imipenem, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), ciprofloxacin, and resistant to erythromycin, kanamycin, ampicillin, gentamicin. After identifying the result of pus culture, the antibiotic regimen was changed to TMP-SMX (15 mg/kg of the TMP component per day) and imipenem 500 mg qid. Due to the persistence of the patient's symptoms, re-imaging was performed two weeks later. On day 24 of admission, the patient underwent a repeated craniotomy with stereotactic aspiration of the abscess because the abscess and surrounding edema have increased than before. Ciprofloxacin (400 mg every 12 h, intravenous) was added to the TMP-SMX treatment and changed from imipenem to meropenem. After performance of repeated surgery and administration of additional antibiotics, we observed improvement of the patient's symptoms. Contrast-enhanced brain CT scan performed three weeks after reoperation, showed substantial resolution of the brain lesion. Meropenem and ciprofloxacin were continued for six weeks. On hospital day 67, he was discharged to go home to complete four months of oral TMP-SMX therapy. On three-month follow-up brain CT after discharge, resolution of the brain abscess was confirmed.

Nocardia species are branching filaments of gram-positive bacteria that are omnipresent in soil and water [5]. Sixteen species of Nocardia have been implicated in human infections [6]. Nocardia infections commonly arise in the immunocompromised states including organ transplants, leukemia, HIV, steroid abuse, and autoimmune disease [1]. Inhalation is the most common route of the infection. Isolated pulmonary infection is most common, followed by disseminated disease (13.5%). Isolated involvement of the skin (8.1%) and central nerve system (5.4%) has also been reported [7].

Nocardia species are a rare cause of cerebral abscess [3]. Nocardia brain abscess appears in a gradually progressive mass lesion, with specific neurologic findings. Seizures and focal neurological deficits are the most common clinical manifestations observed in patients with a Nocardia brain abscess [8]. Our patient was rarely represented with neurologic and toxic symptoms such as seizure, paralysis, dyspnea and fever. Most patients with a Nocardia brain abscess are immunocompromised or have received immunosuppressive therapy [3]. Nocardia brain abscess in an immunocompetent host overseas has rarely been reported, and only one case of Nocardia brain abscess, which accompanied semi-invasive pulmonary Aspergillosis, has been reported in Korea. In this case, the patient was not immunocompromised and had not received immunosuppressive therapy [4, 9, 10, 11].

The mortality rate for Nocardia brain abscess is higher than that for other bacterial cerebral abscesses. In general, the mortality rate for patients with Nocardia infection is three times higher than that for patients with other types of bacterial brain abscess. The higher mortality of Nocardia brain abscess is supposed to be associated with patient's immune state. According to one study, the mortality rate of immunocompromised patients was 55%, whereas the mortality rate of immunocompetent patients was 20% [8, 11].

It is difficult to diagnose the Nocardia infection using culture-based methods because Nocardia species grow slowly and are contaminated by faster growing competitors. The 16S rRNA gene sequencing method is a reliable and fast method for identification of Nocardia species [12]. In this case, colonial morphology, Gram stain, and modified AFB stain suggested Nocardia species. The species was identified as N. farcinica by 16S rRNA gene-based PCR and sequencing.

For diagnosis of a Nocardia brain abscess, it is important to carry out the brain images and surgical interventions. Brain CT, demonstrating a hypodense, enhancing lesion with surrounding edema, is sensitive for discovery and localization of the lesion; however, it is not sufficient for diagnosis. On brain MRI, multiple concentric rims are seen in abscesses due to Nocardia. Because it occasionally occur that necrotic metastasis and brain tumors are wrongly recognized by imaging study, it is required to get a proper specimen through surgical intervention. Besides, in order to prevent treatment delay, early surgical intervention is also required [13].

Although the use of metronidazole and third generation cephalosporins has become the standard for empirical treatment of cerebral abscesses, initial antimicrobial therapy for cerebral nocardiosis was established for the use of TMP-SMX, amikacin, and imipenem because Nocardia species are occasionally resistant to these antibiotics [14, 15, 16]. In particular, TMP-SMX is the preferred initial treatment for a Nocardia brain abscess due to good tolerance and better cerebrospinal fluid penetration [17]. Due to its similar pharmacokinetic effect, good cerebrospinal fluid penetration, and its association with lower occurrence of seizure, meropenem is a theoretically attractive substitute for imipenem for patients with cerebral nocardiosis [18]. Because a nocardial abscess forms multilocular and thick walled lesions, surgical intervention is usually required in most cases of cerebral nocardiosis. Overall prognosis is favorable upon administration of appropriate surgical therapy and antibiotics [17, 19]. In this case, we performed reoperation and added ciprofloxacin to the TMP-SMX because the abscess and surrounding edema have increased than before and the pathogen was susceptible to ciprofloxacin. As a result, the patient has improved after repeated surgical intervention and antibiotics.

In summary, Nocardia species are a rare cause of brain abscess in immunocompetent individuals. In Korea, this is the second report of an immunocompetent patient with a brain abscess caused by N. farcinica.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Beaman BL, Beaman L. Nocardia species: host-parasite relationships. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994; 7:213–264.

2. Brown-Elliott BA, Brown JM, Conville PS, Wallace RJ Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006; 19:259–282.

3. Malincarne L, Marroni M, Farina C, Camanni G, Valente M, Belfiori B, Fiorucci S, Floridi P, Cardaccia A, Stagni G. Primary brain abscess with Nocardia farcinica in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2002; 104:132–135.

4. Joung MK, Kong DS, Song JH, Peck KR. Concurrent nocardia related brain abscess and semi-invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011; 49:305–307.

5. Lai CC, Lee LN, Teng LJ, Wu MS, Tsai JC, Hsueh PR. Disseminated Nocardia farcinica infection in a uraemia patient with idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura receiving steroid therapy. J Med Microbiol. 2005; 54:1107–1110.

6. Saubolle MA, Sussland D. Nocardiosis: review of clinical and laboratory experience. J Clin Microbiol. 2003; 41:4497–4501.

7. Minero MV, Marín M, Cercenado E, Rabadán PM, Bouza E, Muñoz P. Nocardiosis at the turn of the century. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009; 88:250–261.

8. Mamelak AN, Obana WG, Flaherty JF, Rosenblum ML. Nocardial brain abscess: treatment strategies and factors influencing outcome. Neurosurgery. 1994; 35:622–631.

9. Oerlemans WG, Jansen EN, Prevo RL, Eijsvogel MM. Primary cerebellar nocardiosis and alveolar proteinosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998; 97:138–141.

10. Mogilner A, Jallo GI, Zagzag D, Kelly PJ. Nocardia abscess of the choroid plexus: clinical and pathological case report. Neurosurgery. 1998; 43:949–952.

11. Fleetwood IG, Embil JM, Ross IB. Nocardia asteroides cerebral abscess in immunocompetent hosts: report of three cases and review of surgical recommendations. Surg Neurol. 2000; 53:605–610.

12. Tatti KM, Shieh WJ, Phillips S, Augenbraun M, Rao C, Zaki SR. Molecular diagnosis of Nocardia farcinica from a cerebral abscess. Hum Pathol. 2006; 37:1117–1121.

13. Menkü A, Kurtsoy A, Tucer B, Yildiz O, Akdemir H. Nocardia brain abscess mimicking brain tumour in immunocompetent patients: report of two cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2004; 146:411–414. discussion 414.

15. Tourret J, Yeni P. Progress in the management of pyogenic cerebral abscesses in non-immunocompromised patients. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 2003; 154:515–521.

16. Hitti W, Wolff M. Two cases of multidrug-resistant Nocardia farcinica infection in immunosuppressed patients and implications for empiric therapy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005; 24:142–144.

17. Valarezo J, Cohen JE, Valarezo L, Spektor S, Shoshan Y, Rosenthal G, Umansky F. Nocardial cerebral abscess: report of three cases and review of the current neurosurgical management. Neurol Res. 2003; 25:27–30.

18. Wiseman LR, Wagstaff AJ, Brogden RN, Bryson HM. Meropenem. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy. Drugs. 1995; 50:73–101.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download