Abstract

Background

GeneXpert MTB/RIF is a real-time PCR assay with established diagnostic performance in pulmonary and extra-pulmonary forms of tuberculosis. The aim of this study was to assess the contribution of GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay to the management of patients with any form of active tuberculosis in a single large tertiary center in Saudi Arabia, with a special focus on the impact on time to start of antituberculous therapy compared with Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) smears and mycobacterial cultures.

Materials and Methods

Clinical, radiological and laboratory records for all patients who were commenced on antituberculous therapy between March 2011 and February 2013 were retrospectively reviewed.

Results

A total of 140 patients were included, 38.6% of which had pulmonary tuberculosis. GeneXpert MTB/RIF was requested for only 39.2% of patients and was the only reason for starting antituberculous therapy for only 12.1%. The median time to a positive GeneXpert MTB/RIF result was 0 days (IQR 3) compared with 0 day (IQR 1) for smear microscopy (P > 0.999) and 22 days (IQR 21) for mycobacterial cultures (P < 0.001). No patients discontinued antituberculous therapy because of a negative GeneXpert MTB/RIF result.

Conclusions

In a setting wherein physicians are highly experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis, GeneXpert MTB/RIF was remarkably under-utilized and had only a limited impact on decisions related to starting or stopping antituberculous therapy. Cost-effectiveness and clinical utility of routine testing of all smear-negative clinical samples submitted for tuberculosis investigations by GeneXpert MTB/RIF warrant further study.

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to cause considerable morbidity and mortality across the world [1]. Early detection of patients with active TB, especially those with pulmonary disease, is an essential component of any TB control program [2]. For many decades, rapid diagnosis of active tuberculosis depended largely on the finding of acid-fast bacilli on microscopic examination of Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stained smears of clinical material. This method however has limited sensitivity, especially in non-respiratory clinical samples [3]. Automated, liquid mycobacterial culture systems have much better sensitivity and specificity, but still require an average of two or more weeks before a positive result is obtained [4]. Newer, highly sensitive nucleic acid amplification techniques have provided new opportunities for earlier diagnosis of patient with active TB [5]. A number of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are currently in use in clinical laboratories, often as part of routine diagnostic work-up [6, 7]. GeneXpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) is a real-time PCR system that demands minimal technical expertise which has been validated for clinical use in both respiratory and non-respiratory clinical samples [8]. The assay is endorsed by the World Health Organization for the diagnosis of pulmonary TB and is an integral part of its effort to strengthen TB diagnostics in clinical laboratories across the world [9].

A number of studies have demonstrated the robust diagnostic performance of GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay in patients with pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB [10, 11, 12]. In a multicenter study of the feasibility of decentralized GeneXpert MTB/RIF testing, the assay resulted in significant shortening of time to TB diagnosis in patients with both smear-positive and smear-negative pulmonary TB [13]. Such data are not available for patients with extrapulmonary TB.

Over the period from 2000-2009, the overall incidence rate of TB in Saudi Arabia ranged between 14.2 and 16.1 per 100,000 populations [14]. GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay has been available for clinicians in our center to order, in addition to ZN smears and mycobacterial cultures, for the investigation of respiratory and non-respiratory clinical samples since March 2011 [15]. The aim of this study was to assess the contribution of GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay to the management of patients with any form of active TB in our center, with a special focus on the impact on time to start of antituberculous therapy compared with ZN smears and mycobacterial cultures.

This study was undertaken at Prince Sultan Military Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The study site is a large tertiary center serving a population of predominantly employees of the Ministry of Defense and their dependents, the majority of which are Saudi nationals. We used our center's TB notification records to identify all patients who were commenced on antituberculous therapy for a diagnosis of active TB during the period from 1 March 2011 to 28 February 2013. We retrospectively reviewed the clinical details for those patients and retrieved all their radiological and laboratory reports. We identified the basis on which the diagnosis of TB was made and recorded the dates of antituberculous therapy. Patients in whom TB was diagnosed on the basis of a positive ZN smear, mycobacterial culture or GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay were labeled as "microbiological diagnosis". Those in whom the diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical, radiological or histological findings without any positive microbiological investigations were labeled as "empiric diagnosis". GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay was performed according to the manufacturer instructions [15]. The primary objective of the study was to compare the time to starting antituberculous therapy for patients in whom the diagnosis of TB was made on the basis of a positive GeneXpert MTB/RIF result versus those in whom the initial diagnosis was based on ZN smears or mycobacterial cultures.

SPSS for Windows version 21 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to evaluate differences with the cut-off for statistical significance set at 0.05. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicated the deviation of data from normal distribution. Therefore, descriptive statistics were expressed as medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQR), and non-parametric independent sample median test was used to evaluate the differences in median time to reporting and initiation of antituberculous therapy.

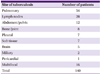

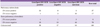

A total of 140 patients were commenced on antituberculous therapy during the study period, including 79 males and 61 females; aged between 13 and 97 years (median 44.5 years). All patients were HIV-negative. Fifty-four patients (38.6%) were treated for pulmonary TB, while 86 patients (61.4%) had extra-pulmonary TB (Table 1). A total of 217 samples were submitted for ZN smear and mycobacterial culture, but GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay was requested for only 85 of them (39.2%). The median time from sampling to reporting was 1 day (IQR 4 days) for GeneXpert MTB/RIF, compared with 1 day (IQR 1 day) for ZN smears (P > 0.999) and 44 days (IQR 30 days) for mycobacterial cultures (P < 0.001).

The majority of patients with pulmonary TB had microbiological evidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection at the time of starting antituberculous therapy. On the other hand, for most patients with extra-pulmonary TB the diagnosis was empiric (Fig. 1). Overall, a positive GeneXpert MTB/RIF result alone was the reason for commencing antituberculous therapy in only 17 out of 140 patients (12.1%); 5 out of 54 pulmonary TB cases (9.3%) and 12 out of 86 patients with extra-pulmonary TB (14.0%). In these patients, positive GeneXpert MTB/RIF results were available earlier than positive cultures by a median of 27 days (IQR 15.5 days). Rifampicin resistance was not detected by GeneXpert MTB/RIF in any of the 85 samples that were tested.

Out of the 67 patients with an empiric diagnosis of TB, the diagnosis was subsequently confirmed by culture in 26 patients (38.8%). GeneXpert MTB/RIF was positive in 9 such patients (13.4%). Of note, mycobacterial cultures were positive for 8 out of those 9 patients, reducing the effective contribution of the GeneXpert MTB/RIF to just one additional microbiologically confirmed diagnosis.

Overall, the median time from a positive GeneXpert MTB/RIF result to starting antituberculous therapy was 0 days (IQR 3 days), compared with a median of 0 (IQR 1 day) for ZN smears (P > 0.999) and a median of 22 days (IQR 21 days) for mycobacterial cultures (P < 0.001). A positive GeneXpert MTB/RIF result was available later than positive ZN smears by a median of 1 day (IQR 3 days) (P > 0.999) and earlier than positive mycobacterial cultures by a median of 22 days (IQR 15.5 days) (P < 0.001).

GeneXpert MTB/RIF was requested on samples from 76 out 140 patients (54.3%). Only 17 out of 67 patients (25.4%) in the empiric diagnosis group had samples tested by GeneXpert MTB/RIF. Antituberculous therapy was not discontinued in any patients because of negative GeneXpert MTB/RIF results.

Thirty-seven (68.5%) out of 54 patients treated for pulmonary TB had positive ZN smears, while 17 (31.5%) had negative ZN smears. Of the latter, GeneXpert MTB/RIF was positive in 4 and negative in 3 patients. Ten patients with ZN-smear negative pulmonary TB did not have their samples tested by GeneXpert MTB/RIF (Table 2). On the other hand, 78 (90.7%) of 86 patients with extra-pulmonary TB had negative ZN-smears, of which 19 (24.4%) had positive GeneXpert RIF/MTB results; whereas 46 (59.0%) did not have any samples tested by GeneXpert (Table 2).

Our study shows that in a real life setting GeneXpert MTB/RIF reduced the time to starting antituberculous therapy by around 4 weeks for patients with negative ZN smears, but not in those for whom positive ZN smear results were available. This benefit was seen in both patients with pulmonary or extra-pulmonary TB.

Given the national and socio-economic background of our patient population, the predominance of extra-pulmonary TB in this study is consistent with the local epidemiology of TB [14]. The study setting was one where physicians are highly experienced in TB and are often willing to commence antituberculous therapy on clinical and radiological grounds, pending microbiological confirmation. Just over half the patients who started antituberculous therapy with an empiric diagnosis had subsequent microbiological confirmation.

GeneXpert MTB/RIF was requested for samples from just over half of all patients (54.3%) and only a quarter of patients with an empiric diagnosis (25.4%). Furthermore, negative GeneXpert MTB/RIF did not result in any antituberculous therapy discontinuation. Moreover, GeneXpert MTB/RIF was positive in 4 out of 17 (23.5%) patients with ZN-smear negative pulmonary TB, while 10 out of those 17 patients (58.8%) did not have their samples tested by GeneXpert at all. These findings demonstrate that over the study period, GeneXpert MTB/RIF was remarkably under-utilized in our center. It also appears that for the diagnosis of active TB, physicians in our setting continue to rely largely on their clinical assessment and traditional microbiological and non-microbiological diagnostic investigations.

Although results from GeneXpert MTB/RIF were available after a median of 1 day, some were delayed for as long as 42 days. The delays were caused by interruptions in the supply chains and logistic difficulties, especially during the first few weeks of introducing the assay. Such inconsistent availability of the test reagents is not unusual in diagnostic laboratories in the developing world where the supply infrastructures are less developed and may hinder achieving the true potential benefits of GeneXpert MTB/RIF in clinical practice is such settings [16].

In a previous study in which the utility of wide application of GeneXpert MTB/RIF was investigated, the study protocol required that sputum samples are submitted for GeneXpert MTB/RIF testing and patients were excluded if that could not be ascertained [13]. In real life practice however, there can be significant differences between physicians in their approach to investigate and treat patients with suspected active TB. Although the excellent performance of GeneXpert MTB/RIF in the diagnosis of active TB is well established, its impact on the clinical management of individual patients appears, like most medical investigations, to be dependent on how well it is utilized in the clinical setting. A protocol-driven approach, such as one stipulating that GeneXpert MTB/RIF tests are routinely performed on ZN smear negative samples from patients with suspected active TB, may help maximize the clinical benefit of such an assay. The cost-effectiveness of such an approach requires careful evaluation. It indeed may not be affordable in healthcare systems with high rates of TB but limited financial resources.

The study is limited by its retrospective nature and the underutilization of GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay. It however reflects real life practice and therefore presents it as it is with its variations and occasional inconsistencies. In conclusion, our study shows that in real life practice, routine availability of GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay can result in considerable shortening of duration to starting antituberculous therapy. However, a systematic protocol for its application and ensuring adequate logistic support are essential for achieving the assay's full potential.

Figures and Tables

References

1. World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2012. Accessed 25 October 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf.

2. Lonnroth K, Castro KG, Chakaya JM, Chauhan LS, Floyd K, Glaziou P, Raviglione MC. Tuberculosis control and elimination 2010-50: cure, care, and social development. Lancet. 2010; 375:1814–1829.

3. Mathew P, Kuo YH, Vazirani B, Eng RH, Weinstein MP. Are three sputum acid-fast bacillus smears necessary for discontinuing tuberculosis isolation? J Clin Microbiol. 2002; 40:3482–3484.

4. van Kampen SC, Anthony RM, Klatser PR. The realistic performance achievable with mycobacterial automated culture systems in high and low prevalence settings. BMC Infect Dis. 2010; 10:93.

5. Pai M, Minion J, Sohn H, Zwerling A, Perkins MD. Novel and improved technologies for tuberculosis diagnosis: progress and challenges. Clin Chest Med. 2009; 30:701–716.

6. Coll P, Garrigó M, Moreno C, Marti N. Routine use of Gen-Probe Amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis Direct (MTD) test for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with smear-positive and smear-negative specimens. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003; 7:886–891.

7. Laraque F, Griggs A, Slopen M, Munsiff SS. Performance of nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of tuberculosis in a large urban setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2009; 49:46–54.

8. Lawn SD, Nicol MP. Xpert(R) MTB/RIF assay: development, evaluation and implementation of a new rapid molecular diagnostic for tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance. Future Microbiol. 2011; 6:1067–1082.

9. World Health Organization. Policy statement : automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF system. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2011. Accessed 25 October 2013. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501545_eng.pdf.

10. Boehme CC, Nabeta P, Hillemann D, Nicol MP, Shenai S, Krapp F, Allen J, Tahirli R, Blakemore R, Rustomjee R, Milovic A, Jones M, O'Brien SM, Persing DH, Ruesch-Gerdes S, Gotuzzo E, Rodrigues C, Alland D, Perkins MD. Rapid molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin resistance. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:1005–1015.

11. Hillemann D, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Boehme C, Richter E. Rapid molecular detection of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by the automated GeneXpert MTB/RIF system. J Clin Microbiol. 2011; 49:1202–1205.

12. Tortoli E, Russo C, Piersimoni C, Mazzola E, Dal Monte P, Pascarella M, Borroni E, Mondo A, Piana F, Scarparo C, Coltella L, Lombardi G, Cirillo DM. Clinical validation of Xpert MTB/RIF for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2012; 40:442–447.

13. Boehme CC, Nicol MP, Nabeta P, Michael JS, Gotuzzo E, Tahirli R, Gler MT, Blakemore R, Worodria W, Gray C, Huang L, Caceres T, Mehdiyev R, Raymond L, Whitelaw A, Sagadevan K, Alexander H, Albert H, Cobelens F, Cox H, Alland D, Perkins MD. Feasibility, diagnostic accuracy, and effectiveness of decent ralised use of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for diagnosis of tuberculosis and multidrug resistance: a multicentre implementation study. Lancet. 2011; 377:1495–1505.

14. Abouzeid MS, Zumla AI, Felemban S, Alotaibi B, O'Grady J, Memish ZA. Tuberculosis trends in Saudis and non-Saudis in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia - a 10 year retrospective study (2000-2009). PLoS ONE. 2012; 7:e39478.

15. Al-Ateah SM, Al-Dowaidi MM, El-Khizzi NA. Evaluation of direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in respiratory and non-respiratory clinical specimens using the Cepheid Gene Xpert(R) system. Saudi Med J. 2012; 33:1100–1105.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download