Abstract

Here, we report a case of primary cryptococcal tenosynovitis and arthritis caused by worsened cellulitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who had been taking methotrexate and leflunomide. The patient, injured during the soybean harvest, failed to respond to empirical antibiotic therapy for presumed bacterial cellulitis on the dorsum of the right hand. An operative procedure was performed. Cryptococcocal tenosynovitis was diagnosed upon histopathological examination of the lesion. Treatment with 400 mg of fluconazole daily for 3 months led to the complete disappearance of skin lesions, with slight limitation of finger extension. The patient was examined continuously for 2 years, and there was no evidence of relapse or dissemination to other organs. This case indicates that primary cryptococcal skin and soft tissue infections must be included in the differential diagnoses of antibiotics-refractory soft tissue infections, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast species present in soil and avian fecal materials. Although C. neoformans is ubiquitous in nature, the incidence of cryptococcosis in patients is relatively low, possibly due to the cell-mediated immune response providing a strong defense against cryptococcal disease[1, 2]. Accordingly, the vast majority of patients with cryptococcosis are also in an immunocompromised state brought on by Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), hematologic malignancies, autoimmune diseases, prolonged treatments with corticosteroids, or organ transplantation[1]. In an impaired immune system, inhaled yeast spores of Cryptococcus can disseminate hematogenously to the central nervous system, skin, and visceral organs, resulting in life-threatening infections[1]. Approximately 15% of patients with systemic dissemination show secondary involvement of the skin. As such, cryptococcal skin disease is commonly regarded as a marker of a disseminated disease state. Recently, it was found that primary cryptococcocal skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) without systemic dissemination following inoculation of infectious matter is a distinct clinical entity[3, 4]. Clinical manifestations of primary cryptococcal SSTI are varied and may include ulcerations, nodules, whitlow, and cellulitis. Among these manifestations, cellulitis is more common in immunocompromised patients and rapidly progresses to deep structures[3-6].

Cryptococcocal tenosynovitis is extremely rare, and most reported cases are associated with preceding disseminated crytococcal infections[7-10]. In this paper, we present a case of primary cryptococcal tenosynovitis and arthritis caused by worsened cellulitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who had been taking methotrexate and leflunomide.

A 69-year-old woman who had lived in a rural area and had an 8-month history of RA presented with painful swelling of the dorsum of the right hand. Ten days prior, she had discovered two scratches on her right hand after harvesting her soybean crop, after which her right hand dorsum had become gradually swollen. Eight months previously, she was diagnosed with RA, and disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), a combination of methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine, were administrated. For 3 months, she was treated with 15 mg of methotrexate weekly and 10 mg of leflunomide daily. As a result, her RA was kept well under control. She did not complain of any respiratory symptoms, headaches, or febrile sensations during the treatment period. Upon physical examination, she presented with tender, erythematous, indurated swelling as well as two tiny skin abrasions about 5×5 mm in size on the dorsum of her right hand. Clinically, she did not look toxic, and there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy or neurological deficits. An initial laboratory investigation revealed increased level of inflammatory markers at an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 73 mm/hr as well as a C-reactive protein of 2.04 mg/dL. The results of an HIV test came back negative. The rest of her laboratory results, including a complete blood count, liver function tests, and urinalysis, were within normal limits. There was no evidence of any parenchymal lesion on her chest X-ray films. In response to potential bacterial cellulitis, antibacterial therapy involving oral administration of 500 mg of cefaclor twice a day was carried out for 7 days. The lesions on her right hand, however, did not heal. A magnetic resonance image of her right hand revealed diffuse effusion along the fourth and fifth extensor tendon sheaths with soft tissue enhancement as well as joint effusion on the 4th metacarpophalangeal joint (Fig. 1). She was subjected to synovectomy. Microscopically, tendon sheath presented with granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells. A few small round yeast cells, surrounded by a clear halo, were stained red in color by Periodic acid-Schiff stain within the granuloma (Fig. 2). The serum cryptococcal antigen turned out to be negative in two consecutive tests. Based on the diagnosis of primary cryptococcal tenosynovitis and arthritis revealed by the histopathological results, she was treated orally with 400 mg of fluconazole daily for 3 months. After 4 months of follow-up, the pain and swelling of her right hand was fully resolved with only slight limitation of finger extension. The patient was examined further for 2 years and there was no evidence of relapse or dissemination to other organs.

Cryptococcal tenosynovitis has been reported previously in immunocompromised patients, most commonly as the result of dissemination[7-10]. Direct inoculation through the skin is a rare but viable possible cause of cryptococcal soft tissue infection, although there has been some controversy[3, 4]. Dozens of cases of primary cryptococcal SSTI, including some domestic cases, have been reported[3-6, 11-15]; however most were cases of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis (PCC). To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports of primary cryptococcal SSTI involving joints. Therefore, this is a unique case of primary cryptococcal tenosynovitis in a RA patient taking non-biologic DMARDs.

Diagnosis of primary cryptococcal SSTI is based on the identification of C. neoformans in the tissue as well as proof of the absence of dissemination[3, 4]. In our case, Cryptococcus spp. was identified upon histopathological examination, and there was no evidence of dissemination. Discrimination between PCC and a secondary infection is an important part of the diagnosis since the prognosis of secondary cryptococcal SSTI is quite different from that of PCC and a different therapeutic regimen is needed. PCC mostly affects patients from rural areas who are involved in jobs or hobbies that predispose oneself to skin wounds as well as exposure to soil and wood debris. The most common clinical features of PCC are cellulitis, ulceration, and whitlow, all of which are solitary or confined to a limited area and located on unclothed areas of the skin. With regard to secondary cutaneous cryptococcosis, umbilicated papules are the most common feature and skin lesions are usually multiple and scattered, located on both clothed and exposed areas (most commonly on the head and neck)[4]. Almost every type of skin lesion, however, can appear during disseminated cryptococcosis. Therefore, careful investigation is required to ascertain a diagnosis of PCC, as some features can be used to differentiate PCC from secondary infection[4]. This work-up should include serum cryptococcal antigen, blood, urine, and sputum cultures, a chest X-ray, and thorough dermatologic examination. If initial tests indicate dissemination or if symptoms suggest central nervous system involvement, then cerebrospinal fluid analysis should be performed[3].

As of yet, there is no consensus with regard to the correct treatment for primary cryptococcal SSTI. Most reported cases of primary cryptococcal SSTI were managed by medical treatment or combined medical and surgical treatments, and the outcomes were favorable[3-6, 16, 17]. The choice of antifungal agents for treating cryptococcal disease depends on the anatomic site of infection as well as the host's immune status[18]. A recent set of guidelines provided by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends oral fluconazole administration (400 mg/day for 6 to 12 months) only if CNS disease is excluded, fungemia is not present, the infection occurs at a single site, and there are no immunosuppressive risk factors[19]. Most reported cases of primary cryptococcal SSTI were treated with azole monotherapy (200 mg-400 mg/day of fluconazole or 200 mg/day of itraconazole for 3 to 6 months), and responses were favorable even in an immunosuppressed state[3, 5, 20]. Although our patient was in an immunosuppressed state, there was no evidence of involvement of the CNS or internal organs. Our patient orally consumed fluconazole for only 3 months, after which she underwent surgery. She was free of all lesions for 2 years after completing the therapy.

The case presented here shows that direct inoculation of contaminated material (soybean, soil, etc.) through a minor skin wound might cause rapidly progressing SSTI in patients subjected to long-term therapy with immunosuppressive agents. Cryptococcal SSTI is usually mistaken as a bacterial infection and initially treated with antibacterial agents. Thus, a primary cryptococcal infection should be included in the differential diagnosis of antibiotics-refractory soft tissue infection, especially in immunocompromised patients with a history of physical trauma and simultaneous contact with a possibly contaminated material. Further, this case supports the use of fluconazole and surgery as a single therapy for the treatment of primary cryptococcal infection.

Figures and Tables

Figure 1

T1 weighted post-gadolinium images (A, B) show a multilobulated and low signaled lesion (arrows) with peripheral soft tissue enhancement along the right fourth and fifth extensor tendons. There is a high signal (arrow) in and around the metacarpophalangeal joint of the right fourth finger in the coronal image (C).

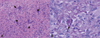

Figure 2

The surgical specimen of the tendon sheath shows granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells (arrows), which contain small round yeast cells presenting with a foamy cytoplasm surrounded by a clear halo (H & E ×200) (A). Periodic acid-Schiff staining of tissues reveals yeast cells (arrow) that display intense red staining along their rim (PAS ×400) (B).

References

2. Lin X, Heitman J. The biology of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006. 60:69–105.

3. Christianson JC, Engber W, Andes D. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Med Mycol. 2003. 41:177–188.

4. Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, Dupont B, Ronin O, Lortholary O. French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003. 36:337–347.

5. Hafner C, Linde HJ, Vogt T, Breindl G, Tintelnot K, Koellner K, Landthaler M, Szeimies RM. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis and secondary antigenemia in a patient with long-term corticosteroid therapy. Infection. 2005. 33:86–89.

6. Zorman JV, Zupanc TL, Parac Z, Cucek I. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a renal transplant recipient: case report. Mycoses. 2010. 53:535–537.

7. Bruno KM, Farhoomand L, Libman BS, Pappas CN, Landry FJ. Cryptococcal arthritis, tendinitis, tenosynovitis, and carpal tunnel syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Arthritis Rheum. 2002. 47:104–108.

8. Horcajada JP, Peña JL, Martínez-Taboada VM, Pina T, Belaustegui I, Cano ME, García-Palomo D, Fariñas MC. Invasive Cryptococcosis and adalimumab treatment. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007. 13:953–955.

9. Chung SM, Lee EY, Lee CK, Eom DW, Yoo B, Moon HB. A case of cryptococcal tenosynovitis in a patient with Wegener's granulomatosis. J Korean Rheum Assoc. 2004. 11:66–71.

10. Park J, Ostrov BE, Schumacher HR Jr. Cryptococcal tenosynovitis in the setting of disseminated cryptococcosis. J Rheumatol. 2000. 27:282–283.

11. Kang HY, Kim NS, Lee ES. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis treated with fluconazole. Korean J Dermatol. 2000. 38:838–840.

12. Kim DH, Kim M, Kim SJ, Lee SC, Won YH. A case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in a patient with iatrogenic Cushing's syndrome. Korean J Med Mycol. 1998. 3:195–199.

13. Kim HJ, Min HG, Lee ES. Two cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis mimicking cellulitis. Korean J Med Mycol. 1998. 3:190–194.

14. Kim YJ, Seo SJ, Ro BI. A case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis misdiagnosel as skin tuberculosis. Korean J Med Mycol. 2003. 8:16–20.

15. Probst C, Pongratz G, Capellino S, Szeimies RM, Schölmerich J, Fleck M, Salzberger B, Ehrenstein B. Cryptococcosis mimicking cutaneous cellulitis in a patient suffering from rheumatoid arthritis: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2010. 10:239.

16. Leão CA, Ferreira-Paim K, Andrade-Silva L, Mora DJ, da Silva PR, Machado AS, Neves PF, Pena GS, Teixeira LS, Silva-Vergara ML. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis caused by Cryptococcus gattii in an immunocompetent host. Med Mycol. 2011. 49:352–355.

17. Pau M, Lallai C, Aste N, Aste N, Atzori L. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent host. Mycoses. 2010. 53:256–258.

18. Saag MS, Graybill RJ, Larsen RA, Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Powderly WG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000. 30:710–718.

19. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, Harrison TS, Larsen RA, Lortholary O, Nguyen MH, Pappas PG, Powderly WG, Singh N, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2010. 50:291–322.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download