Abstract

We report a case of 58-year-old female with scrub typhus who presented with Bell's palsy. Five days after the initiation of treatment, she developed complete peripheral facial palsy on the right side of her face. Oral corticosteroid, intravenous immunoglobulin, and acyclovir were administered but her Bell's palsy showed no signs of improvement even after one year of regular follow-up at the outpatient department.

Bell's palsy is an idiopathic, acute peripheral facial nerve palsy, characterized by inability to show facial expressions [1]. Bell's palsy is believed to be caused by inflammation of the facial nerve, most commonly at the geniculate ganglion [1]. HSV type 1 is probably the most frequent cause of Bell's palsy [2, 3]. Other frequently associated conditions include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, HIV infection, Lyme disease, herpes zoster, sarcoidosis, and amyloidosis [1, 2]. Peripheral facial nerve palsy has also been reported among recipients of inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine [4]. Scrub typhus is an acute febrile illness caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi, which is transmitted to humans through bite of the larva of trombiculid mites. Major pathology of scrub typhus is involvement of vascular endothelial cells, which induces focal or disseminated vasculitis due to the destruction of endothelial cells, and many organ-system dysfunctions [5, 6]. Exhaustive studies with scrub typhus have revealed that the central nervous system is involved in almost all cases, however mild it may be, while involvement of focal peripheral nervous system is rare [7] and no case has ever been reported. Here, we report a case of unilateral facial palsy encountered while the patient was undergoing treatment for O. Tsutsugamushi infection.

A 58-year-old previously healthy woman was referred to the Department of Neurology at Chonbuk National University Hospital on October 27th, 2008 with fever, nausea, vomiting, and headache of 10 days' duration. She also showed neck stiffness at initial examination. On the first day, while she was still in the emergency room, we withdrew cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for differential diagnosis. The CSF study showed the following results: white blood cell (WBC) count, 31/mm3 (neutrophils 98% and lymphocytes 2%); red blood cell (RBC) count, 2/mm3; protein, 83 mg/dL; and glucose, 55 mg/dL. An eschar was detected on the abdomen. Initial hematology and blood chemistry findings were as follows: WBC count, 12,300/mm3; platelet count, 104,000/mm3; aspartate aminotransferase, 235 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 232 U/L; sodium, 139 mmol/L; and potassium, 3.7 mmol/L. The serum antibody titer to O. tsutsugamushi, using indirect immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) assay was 1:320. The follow up antibody titer was elevated to 1:5,120 after 10 days. On the basis of clinical findings and laboratory examinations, she was diagnosed with scrub typhus complicated by meningitis and treated with doxycyclin, ceftriaxone, and mannitol.

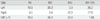

After initial treatment with doxycycline, her condition gradually improved. However, on the 5th post-treatment day, she felt lax and the muscle on the right side of her face became droopy. Neurologic examination revealed unilateral facial palsy without any other preceding symptoms (Fig. 1). She also complained of decreased sense of taste (dysgeusia) and decreased salivary secretion. However, she denied hearing impairment or decreased lacrimation. Blink reflex test (Table 1) done by stimulating the affected right side resulted in an absent ipsilateral (right) R1 and R2 potentials but a normal contralateral (left) R2, whereas stimulating the unaffected left side resulted in a normal ipsilateral (left) R1 and R2 but an absent contralateral (right) R2, indicating complete right facial palsy. Facial nerve excitability tests showed absence of nerve excitability on the right side. Serological tests to screen for other infectious causes of Bell's palsy, including HSV IgM for herpes simplex virus, cold agglutinin test for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, CMV IgM for cytomegalovirus, viral capsid antigen (VCA) IgM, Epstein-Barr early antigen (EBEA)-D for Epstein-Barr virus, and HIV Ab for human immunodeficiency virus were all negative; however, polymerase chain reaction for HSV infection was not performed. Brain computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast enhancement showed no abnormality. After the diagnosis of Bell's palsy was made, oral corticosteroid was administered for 16 days, intravenous immunoglobulin for 5 days, and acyclovir for 7 days. At one-year post-discharge follow-up, the patient still had the same degree of facial palsy without any signs of improvement.

Scrub typhus is endemic across much of Asia and the Western Pacific region, causing substantial morbidity in these areas [5, 8]. It is an acute febrile illness characterized by abrupt fever, chills, rash, lymphadenopathy, abdominal pain, myalgia, and eschar [9, 10]. Various complications were reported in scrub typhus cases including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), encephalitis, interstitial pneumonia, myocarditis and pericarditis, acute renal failure, and acute hepatic failure [5, 11-14]. Recently, Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with scrub typhus was reported in Korea [15].

Bell's palsy occurs in 20 to 30 persons per 100,000 population per year and affects both sexes in all ages. Approximately two thirds of Bell's palsy is idiopathic [2]. The remaining one third is caused by trauma, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, sarcoidosis, etc. An association between infectious diseases and Bell's palsy was reported in Herpes simplex virus type 1, Lyme disease, and HIV infection [1, 2]. Neither Bell's palsy nor focal peripheral nerve system involvement following scrub typhus has been previously reported or systematically investigated.

Viral infections including cytomegalovirus infection, herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus infection, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV infection have been associated with vasculitic neuropathy [6]. Lyme disease is also associated with polyradiculopathy. The main pathologic changes of scrub typhus are focal or disseminated vasculitis due to the destruction of endothelial cells lining of small vessels and perivascular infiltration of leukocytes [6, 16]. Classically, patients with vasculitic neuropathy have painful sensory loss and weakness in the distribution of multiple peripheral nerves, which is referred to as mononeuritis multiplex [17]. In present case, we postulated that the operating mechanism of Bell's palsy in this patient with scrub typhus was vasculitic focal neuropathy caused by O. tsutsugamushi.

Our patient also had meningitis associated with scrub typhus. Aseptic meningitis is commonly associated with facial nerve paralysis in HIV-1 infected patients and in Lyme disease.

Fortunately, most patients with Bell's palsy recover completely, but 20 to 30% may be left with permanent, disfiguring facial weakness or paralysis [18]. Poor prognostic factors include old age, hypertension, impairment of taste, pain in other parts of the body that is not localized to the ear, and complete facial weakness [2]. When excitability is retained, 90% of patients recover completely [19, 20]. However, in the absence of excitability, only 20% of patients recover completely. In the present case, the patient had poor prognostic factors such as old age, complete facial weakness, and absence of excitability. About 1 year had lapsed since she was treated, but she showed no signs of recovery.

There is a limitation in this study. Although serology for herpes simplex virus was negative, polymerase chain reaction of CSF should have been carried out to completely rule out the possibility of herpes simplex infection, since it is the most common cause of Bell's palsy. However, we believe that the presence of pathognomonic eschar and definitive serologic findings were sufficient evidence to reasonably conclude that the cause of Bell's palsy had been scrub typhus.

To our knowledge, the present case is the first reported case on Bell's palsy associated with scrub typhus. This study indicates that scrub typhus should also be included in the differential diagnosis of Bell's palsy in areas where O. tsutsugamushi is endemic. Further studies are needed to understand the clinical characteristics of Bell's palsy with scrub typhus and to elucidate pathophysiology of Bell's palsy in scrub typhus.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1On admission, the patient shows loss of wrinkling in the right forehead and is unable to close the right eye tightly, puff up the cheeks, and make upward movement of the right upper eyelid (A). The mouth is deviated to the left (B). |

Table 1

Result of Blink Reflex. Stimulating the unaffected left side (A) and recording of both orbicularis oculi muscles result in a normal ipsilateral R1 and R2 but an absent contralateral (right) R2. Stimulating the affected right side (B) result in an absent ipsilateral (right) R1 and R2 potentials, but a normal contralateral R2

References

1. Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell's palsy: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007. 76:997–1002.

2. Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell's Palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004. 351:1323–1331.

3. Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Nakashiro Y, Doi T, Hato N, Yanagihara N. Bell palsy and herpes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle. Ann Intern Med. 1996. 124:27–30.

4. Mutsch M, Zhou W, Rhodes P, Bopp M, Chen RT, Linder T, Spyr C, Steffen R. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell's palsy in Switzerland. N Engl J Med. 2004. 350:896–903.

5. Song SW, Kim KT, Ku YM, Park SH, Kim YS, Lee DG, Yoon SA, Kim YO. Clinical role of interstitial pneumonia in patients with scrub typhus: a possible marker of disease severity. J Korean Med Sci. 2004. 19:668–673.

6. Strickman D, Smith CD, Corcoran KD, Ngampochjana M, Watcharapichat P, Phulsuksombati D, Tanskul P, Dasch GA, Kelly DJ. Pathology of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi infection in Bandicota savilei, a natural host in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994. 51:416–423.

7. Kim DE, Lee SH, Park KI, Chang KH, Roh JK. Scrub typhus encephalomyelitis with prominent focal neurologic signs. Arch Neurol. 2000. 57:1770–1772.

8. Thap LC, Supanaranond W, Treeprasertsuk S, Kitvatanachai S, Chinprasatsak S, Phonrat B. Septic shock secondary to scrub typhus: characteristics and complications. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002. 33:780–786.

9. Watt G, Parola P. Scrub typhus and tropical rickettsioses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003. 16:429–436.

10. Berman SJ, Kundin WD. Scrub typhus in south Vietnam. A study of 87 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1973. 79:26–30.

11. Wang CC, Liu SF, Liu JW, Chung YH, Su MC, Lin MC. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007. 76:1148–1152.

12. Tsay RW, Chang FY. Serious complications in scrub typhus. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 1998. 31:240–244.

13. Chang JH, Ju MS, Chang JE, Park YS, Han WS, Kim IS, Chang WH. Pericarditis due to Tsutsugamushi disease. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000. 32:101–102.

14. Chang JH, Ju MS, Chang JE, Park YS, Han WS, Kim IS, Chang WH. Pericarditis due to Tsutsugamushi disease. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000. 32:101–102.

15. Lee SH, Jung SI, Park KH, Choi SM, Park MS, Kim BC, Kim MK, Cho KH. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with scrub typhus. Scand J Infect Dis. 2007. 39:826–828.

16. Kim SJ, Chung IK, Chung IS, Song DH, Park SH, Kim HS, Lee MH. The clinical significance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in gastrointestinal vasculitis related to scrub typhus. Endoscopy. 2000. 32:950–955.

17. Gorson KC. Vasculitic neuropathies: an update. Neurologist. 2007. 13:12–19.

18. Peitersen E. The natural history of Bell's palsy. Am J Otol. 1982. 4:107–111.

19. Campbell ED, Hickey RP, Nixon KH, Richardson AT. Value of nerve-excitability measurements in prognosis of facial palsy. Br Med J. 1962. 2:7–10.

20. Richardson AT. Electrodiagnosis of facial palsies. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1963. 72:569–580.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download