Abstract

Background

Although there more than 1,000 liver transplantations (LTs) are performed in Korea annually, their immense cost remains a great hurdle. Hence, in an attempt to reduce the medical costs of LT, a program was initiated at a public hospital affiliated with the Seoul National University Hospital.

Methods

A total of 11 LTs have been successfully executed since the first LT performed at Seoul Metropolitan Government Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center in July 2011 through December 2014.

Results

Nine patients (81.8%) were male and two (18.2%) were female. The mean age of patients was 53.4±11.4 years. Hepatitis B virus-related liver disease (n=6, 54.5%) was the most common causative disease, followed by alcoholic liver disease (ALD) (n=4,36.4%). The actuarial 3-year survival rate was 90.9%. The median total medical cost of LTs was US $41,583 (calculated from operation to discharge), but only $11,860 was actually charged for patients with health insurance coverage. One female patient who had undergone deceased donor LT for alcoholic liver cirrhosis died during follow-up. This patient was non-compliant with the medical instructions after discharge, and finally expired due to septic shock at 10 months post-LT.

Conclusions

In the public hospital, LT was successfully performed at a much lower cost. However, LT guidelines and peritransplant management protocols for patients with ALD must be established before escalating LT at public hospitals since ALD with poor compliance is one of the most common causes of complications at public hospitals.

Liver transplantation (LT) has developed rapidly in the 1980s, with continual improvements in patient survival as a result of advances in immunosuppression and medical management, technical achievements, and improvements in procurement and preservation(1234). Recent data shows that the 1- and 5-year patient survival after LT are 85% to 90% and 70% to 80%, respectively(56). Thus, LT is now considered one of the most effective treatment options for end-stage liver disease, and even for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)(57). Korea is one of the endemic areas of chronic liver disease and HCC. Hence, although the first LT of Korea was performed in 1988, annual cases have exceeded 1,000 in the past 20 years(4). In 2012, the number of LT per population in Korea was 23.2 per million people, which is one of the highest incidence in the world(4).

During the last decade, the Korean medical insurance system has gradually expanded coverage for the procedures and medicines directly related to LT. Nonetheless, the high expense of LT is still big hurdle that patients need to overcome. Normally at least America dollar (US $) 30,000 is required to undergo LT and get discharged, despite the medical insurance coverage. In addition, increasing costs could be incurred due to major post-operative complications and expenses for long-term maintenance after LT. In addition, patients with chronic liver disease have limited finance because of long-term treatment for disease and decreased ability to work. Hence, most patients hesitate to undergo LT, and some even forgo their only option which would enable them to lead a better quality of life and long-term survival.

LT has been performed in more than 40 centers in Korea(4), most of which were university hospitals or tertiary referral hospitals. Since LT requires special equipment, and at least two or three experts with specific skill set, these unfortunately are the factors that increase the total cost of LT. Hence, Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) planned a LT program at a public hospital; the preliminary procedure was performed at Seoul Metropolitan Government Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center (SMG-SNU BMC) in 2011. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the outcomes of early LTs performed at that hospital, and to assess the cost reducing effect.

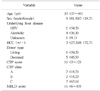

One of the municipal hospitals of Seoul, SMG-SNU BMC is totally operated by SNUH. SNUH had been planning LT at public hospitals, with an aim to improve accessibility to the procedure by reducing the financial burden and making it affordable to patients. The first procedure was finally performed at SMG-SNU BMC in July 2011. After that, a total of 23 LTs were performed at BMC, until December 2017. Eleven patients (nine males [81.8%] and two females [18.2%]) who underwent LT in the early period, from the initiation till December 2014, were enrolled in the present study. The preoperative data of patients, including demographics, underlying liver disease, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score, and type of LT are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients at the time of LT was 53 years (range, 37 to 69 years). The most common causative disease was hepatitis B virus related liver disease (54.5%), followed by alcoholic liver disease (ALD). The median CTP and MELD score of patients were 11 (range, 5 to 12; nine in living donor LT [LDLT] and 11 in deceased donor LT [DDLT]) and 15 (range, 6 to 43; 14 in LDLT and 19 in DDLT). Median follow-up duration of patients was 47.1 months (range, 10.0 to 69.2 months).

The operation data, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and the length of hospital stay were retrospectively investigated from medical records. In addition, total and deductible medical costs were calculated. Data on medical cost were obtained from the hospital administration. Total cost was computed by totaling up all expenses incurred for transplant procedure and post-operative management, from the day of surgery to the discharge. The preoperative cost, which was highly variable due to patient's underlying disease and condition, were excluded in the present study. The deductible cost was defined as the total amount which was actually charged to the patient under the health insurance coverage. Both costs included donor-related medical expenses which incurred in LDLT situation. The Korean won (₩) was converted to the US $ by the won-dollar exchange rate of ₩1,150 per $. The major post-transplant morbidity was defined as complications of grade III or higher, based on the Clavien-Dindo classification(89). The actuarial survival of patients was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 analysis software (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of SMG-SNU BMC (No. 26-2015-89). The informed consent was waived.

Elective LT from living donor was performed in six patients (54.5%), and remaining patients (45.5%) underwent emergent LT from deceased donor. The blood type relationship between the donor and the recipient was ABO identical or compatible for all cases. Modified right liver grafts were used in all LDLT cases. Middle hepatic vein branches were reconstructed with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene artificial grafts. Whole liver grafts were used in all DDLT cases. Neither the cell savor nor veno-venous bypass was used during the operation. The median operation time was 420 minutes (range, 260 to 585 minutes), and the median total ischemic time was 182 minutes (range, 77 to 430 minutes). The median graft to recipient weight ratio (GRWR) was 1.29 (range, 0.90 to 3.79), 1.11 for LDLT and 2.39 for DDLT. The operation data are shown in Table 2.

Median hospital stay from surgery to discharge was 21 days (range, 9 to 103 days). Neither operative nor hospital mortality was recorded. However, seven patients (63.6%) experienced major complications directly related to LT. All complications were grade III, according to Clavien-Dindo classification(8,9). Five patients (45.5%) had biliary complications which required radiological or endoscopic intervention (IIIa) for three cases, and operational management (IIIb) for two patients. During the early postoperative period, three intra-abdominal bleeding cases were reported. One was controlled by means of radiological intervention (IIIa), and two required re-operation (IIIb). The actuarial 3-year survival was 90.9%. Among four patients who underwent LT for ALD, two patients started to drink again in a short period post-LT. One of those died within 1 year after LT.

The only mortality case during follow-up was a 45-year-old woman who had undergone emergency DDLT for ALD. At the time of LT, she was suffering from intractable ascites, and her CTP and MELD score were 11 and 19, respectively. She was extremely cachexic, and her weight and body mass index were only 36 kg and 13.7, respectively. The whole liver graft was received from a 54-year-old male, brain dead donor, and the GRWR was 3.79. Alcohol abstinence before LT was less than 3 months. Liver function was rapidly restored after LT, and she did not have any major complications. However, improvement of physical activity was tardy due to pre-existing muscle wasting. Eventually, she was discharged on the postoperative 30th day, after rehabilitation of several weeks.

However, she had poor compliance. She did not obey the medical instructions after discharge, and was irregular in her visits to the outpatient clinic. Her medication and life style could not be controlled. It was assumed that she relapsed to alcohol ingestion right after discharge. Her husband, the only family member who could care for her, was tied up with work and was unable to attend to her during day time. In addition, she was non-compliant with her husband as well as the medical team of the hospital. Hence, the post-LT management for her was completely failed. She was finally admitted to the emergent center for general weakness and fever at post-LT 9.6 months. She had aggravated liver function, enormous ascites and had a septic condition. She rapidly progressed to septic shock and expired 10 days later, despite aggressive management.

The total medical cost of the patients is shown in Table 3. The median cost, from LT to discharge, was $41,583 (₩47,820,666; range, $35,016 to 78,955). It was $40,960 (₩47,104,481; range, $35,016 to 48,009) for LDLT, and $44,757 (₩51,470,232; range, $38,924 to 78,955) for DDLT. The cost tended to be higher for DDLT, but the mean cost was not statistically significant (P=0.177). Under the health insurance coverage, only $11,860 (₩13,639,500; range, $6,239 to 21,673) was actually charged to patients ($11,816 for LDLT, $11,860 for DDLT). Ten patients (91%), excluding one DDLT patients with a long hospital stay of 103 days, paid less than $14,000 for deductibles.

This study has considered that the SMG-SNU BMC was the only public hospital actively performing LTs at present. Although the total number of cases is small compared to several major transplant centers of Korea, it would be meaningful that the first step was made to generalize LT, which is one of the skill-intensive medical procedures, and to improve the accessibility to LT financially. However, to evaluate the actual efficacy of LT at public hospitals, both clinical outcomes and economic advantages should be considered. In terms of these aspects, the present study reveals the early results of our series. The post-transplant survival rate of initial 11 LT cases at SMG-SNU BMC was 90.9% at 3-years, which was comparable to those of other series, although the number of cases was so small that the actuarial survival rate might not be statistically significant(101112). Although 1 mortality developed in the post-LT first year, it was not directly related to either a technical problem or in-hospital patient care. Poor compliance of the patient and poor family support was responsible for her sudden deterioration and death. On the other hand, the complication rate was a little high, with the complication rate of the Clavien-Dindo grade III or higher being 63.6% in the present study. The corresponding complication rate was 43.3% in the series of Uchiyama and colleagues(13), which included 321 LDLT cases. In addition, complications recorded were 48% for LDLT and 37% for DDLT in the study by Reichman and colleagues(12). However, the incidence of grade IV or V complication was 13% to 15% in their series, while such life-threatening complications did not develop in our current study. The high complication rate of our study could have resulted from technical problems during surgery. Therefore, the complication rate could be expected to gradually decrease, with increasing and accumulating cases in the near future.

LT is one of the most expensive treatment modalities. The complexity of the surgical procedure requires an expert team consisting of highly trained medical personnel, with long hours of experience(14). The amount of medication administered during post-LT care and surgery is high, and special equipment could be required, depending on the patient's condition. In addition, high complication rate after LT frequently requires radiologic or surgical interventions; thus, increasing the expenses(14). According to a survey by Rodrigue and colleagues(15), about half of the patients had a decreased monthly income and experienced financial problems after LT. Thus, the cost of LT is a heavy burden for patients who are considering it, with finance being one of the major concerns. Several studies have projected this issue in different ways(5). Some considered only hospitalization expenses for LT until discharge, whereas others also included the expenses for patient care before and after LT(5). The cost of LT is higher in the US compared to other countries, which might be due to the health system characteristics( 14). Englesbe and colleagues(16) reported in 2006 that the total medical cost for LT and clinical follow-up was $194,840 at their center. According to the study by Buchanan et al.(17) which analyzed the nationwide data, at least more than $270,000 was required during the transplant admission period to post-LT 90 days, which increased depending on the MELD score of the patient. The LT cost in Japan was reported to be lower than that in the United States. Although the design calculating the cost was a little different between studies, it largely ranged from $82,000 to 154,000(7141819).

To our knowledge, no studies regarding the LT cost in Korea have been reported. However, it is well-known that patients pay at least around $30,000 for deductibles under the health insurance coverage for surgery and hospital care during the transplant admission period. Thus, the total cost for LT can be assumed to be over $100,000, which is similar to that of Japan. In the present study, the median total cost for LT was $41,583, of which the patients paid only $11,860. It was showed that the medical cost for LT could be markedly reduced at a public hospital. It was assumed that the cost reduction mainly resulted from the items not covered by the health insurance. Although more and more items for LT have been getting covered by insurance in Korea, non-reimbursable items, including an ultrasound examination and an isolated bed, are still required during surgery and for post-LT management. The medical charge of a non-reimbursable service is not controlled by the government in Korea, but it is dependent on each institution. SMG-SNU BMC is a municipal hospital which is finically supported by the Metropolitan Government. Thus, non-reimbursable service charges can be quite low in SMG-SNU BMC. For example, patients need to be isolated in a 1- or 2-patient room right after LT, due to their severely compromised immunity, and these beds are very expensive in Korea, especially in the portion directly charged to patients. However, the fee of a solitary room bed in SMG-SNU BMC is less than 50% of that in most university hospitals or tertiary referral hospitals. This public hospital effect on cost reduction has also been reported in a recent Spanish study. The mean cost of LT performed in a community hospital was only $33,461 in that study(20), which is thought to be the lowest cost ever to be reported. LT at a public hospital could therefore contribute to significantly reduce the medical cost, and thus to help patients to undergo LT more readily.

ALD is an important issue in LT at public hospitals. ALD usually occupies less than 10% of all LT cases in Korea(2122). Even if the low proportion of ALD might be partially because patients with ALD more frequently fail to undergo LDLT due to poor family condition, ALD patients awaiting DDLT also do not exceed 15% of the waiting list(23). Nonetheless, the proportion of patients who underwent LT for ALD at SMG-SNU BMC was as high as 36.4%. Many alcoholic patients can be more dependent on public hospitals, where medical expenses are relatively cheaper than others, because they are possibly in the low social economic strata due to decreased economic activity. However, LT for ALD is highly controversial. Post-LT alcohol recidivism and low medical compliance are frequently encountered, eventually leading to poor survival(2425). The only mortality case in the present study followed this fatal course. Hence, many transplant centers worldwide request an abstinence duration of at least 6 months before LT for patients with ALD, in order to prevent useless LTs and to improve post-LT outcomes(26). However, there is neither regulation nor consensus on LT for patients with ALD in Korea. Patient selection for LT for ALD totally depends on the decision of each transplant center. In this situation, indiscriminate LTs for ALD might worsen the overall outcomes of LT. In addition, systematic management protocol for ALD patients has not been established in SMG-SNU BMC. Therefore, although the necessity and effect of pre-LT abstinence is also still controversial(272829), the LT guideline for ALD and perioperative alcohol-rehabilitation system needs to be established before the activation of LT at public hospitals.

Our study showed that LT at a public hospital decreases the cost of LT to an acceptable level, with comparable results. The expansion of LT to public hospitals could give a chance of life to patients with limited finance. However, the portion of ALD is higher in the public hospitals, and patients with ALD could have post-LT recidivism and low compliance, resulting in poor prognosis even after LT. Therefore, establishing a LT guideline for ALD patients, including indication criteria and perioperative management protocol, are required before further expansion of LT at public hospitals. The current study was based on limited data from early experience of LT in SMG-SNU BMC. To confirm the present results, further evaluation using accumulated data is required in future.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Jain A, Reyes J, Kashyap R, Dodson SF, Demetris AJ, Ruppert K, et al. Long-term survival after liver transplantation in 4,000 consecutive patients at a single center. Ann Surg. 2000; 232:490–500.

2. Bilbao I, Armadans L, Lazaro JL, Hidalgo E, Castells L, Margarit C. Predictive factors for early mortality following liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2003; 17:401–411.

3. Busuttil RW, Farmer DG, Yersiz H, Hiatt JR, McDiarmid SV, Goldstein LI, et al. Analysis of long-term outcomes of 3200 liver transplantations over two decades: a single-center experience. Ann Surg. 2005; 241:905–916.

4. Lee SG, Moon DB, Hwang S, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Song GW, et al. Liver transplantation in Korea: past, present, and future. Transplant Proc. 2015; 47:705–708.

5. Akarsu M, Matur M, Karademir S, Unek T, Astarcioglu I. Cost analysis of liver transplantation in Turkey. Transplant Proc. 2011; 43:3783–3788.

6. Lim KB, Schiano TD. Long-term outcome after liver transplantation. Mt Sinai J Med. 2012; 79:169–189.

7. Sakata H, Tamura S, Sugawara Y, Kokudo N. Cost analysis of adult-adult living donor liver transplantation in Tokyo University Hospital. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011; 18:184–189.

8. Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004; 240:205–213.

9. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009; 250:187–196.

10. Chan SC, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wei WI, Chik BH, et al. A decade of right liver adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: the recipient mid-term outcomes. Ann Surg. 2008; 248:411–419.

11. Moon DB, Lee SG, Hwang S, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Ha TY, et al. More than 300 consecutive living donor liver transplants a year at a single center. Transplant Proc. 2013; 45:1942–1947.

12. Reichman TW, Katchman H, Tanaka T, Greig PD, McGilvray ID, Cattral MS, et al. Living donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation: a surgeon-matched comparison of recipient morbidity and outcomes. Transpl Int. 2013; 26:780–787.

13. Uchiyama H, Shirabe K, Kimura K, Yoshizumi T, Ikegami T, Harimoto N, et al. Outcomes of adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation in 321 recipients. Liver Transpl. 2016; 22:305–315.

14. van der Hilst CS, Ijtsma AJ, Slooff MJ, Tenvergert EM. Cost of liver transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the United States with other OECD countries. Med Care Res Rev. 2009; 66:3–22.

15. Rodrigue JR, Reed AI, Nelson DR, Jamieson I, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. The financial burden of transplantation: a single-center survey of liver and kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2007; 84:295–300.

16. Englesbe MJ, Dimick J, Mathur A, Ads Y, Welling TH, Pelletier SJ, et al. Who pays for biliary complications following liver transplant? A business case for quality improvement. Am J Transplant. 2006; 6:2978–2982.

17. Buchanan P, Dzebisashvili N, Lentine KL, Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR. Liver transplantation cost in the model for end-stage liver disease era: looking beyond the transplant admission. Liver Transpl. 2009; 15:1270–1277.

18. Ishida K, Imai H, Ogasawara K, Hagiwara K, Furukawa H, Todo S, et al. Cost-utility of living donor liver transplantation in a single Japanese center. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006; 53:588–591.

19. Kogure T, Ueno Y, Kawagishi N, Kanno N, Yamagiwa Y, Fukushima K, et al. The model for end-stage liver disease score is useful for predicting economic outcomes in adult cases of living donor liver transplantation. J Gastroenterol. 2006; 41:1005–1010.

20. Boerr E, Anders M, Mella J, Quinonez E, Goldaracena N, Orozco F, et al. Cost analysis of liver transplantation in a community hospital: association with the Model for End-stage Liver Disease, a prognostic index to prioritize the most severe patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013; 36:1–6.

21. Ahn CS, Hwang S, Kim KH, Moon DB, Ha TY, Song GW, et al. Long-term outcome of living donor liver transplantation for patients with alcoholic liver disease. Transplant Proc. 2014; 46:761–766.

22. Kim JM, Kwon CH, Joh JW, Han SB, Sinn DH, Choi GS, et al. Case-matched comparison of ABO-incompatible and ABO-compatible living donor liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 2016; 103:276–283.

23. Hwang S, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Moon DB, Ha TY, Song GW, et al. Survival rates among patients awaiting deceased donor liver transplants at a single high-volume Korean center. Transplant Proc. 2013; 45:2995–2996.

24. Cuadrado A, Fabrega E, Casafont F, Pons-Romero F. Alcohol recidivism impairs long-term patient survival after orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2005; 11:420–426.

25. Satapathy SK, Eason JD, Nair S, Dryn O, Sylvestre PB, Kocak M, et al. Recidivism in liver transplant recipients with alcoholic liver disease: analysis of demographic, psychosocial, and histology features. Exp Clin Transplant. 2015; 13:430–440.

26. Singal AK, Duchini A. Liver transplantation in acute alcoholic hepatitis: current status and future development. World J Hepatol. 2011; 3:215–218.

27. Karim Z, Intaraprasong P, Scudamore CH, Erb SR, Soos JG, Cheung E, et al. Predictors of relapse to significant alcohol drinking after liver transplantation. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010; 24:245–250.

28. Kollmann D, Rasoul-Rockenschaub S, Steiner I, Freundorfer E, Gyori GP, Silberhumer G, et al. Good outcome after liver transplantation for ALD without a 6 months abstinence rule prior to transplantation including post-transplant CDT monitoring for alcohol relapse assessment: a retrospective study. Transpl Int. 2016; 29:559–567.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download