Abstract

Background

This study was conducted to analyze the current system for allocation of deceased donor kidney transplantation in Korea, which includes an incentive regulation for candidates registered at the Hospital-based Organ Procurement Organization (HOPO).

Methods

Between January 2011 and November 2016, there were 2,655 deceased donors in Korea. During the same period, there were 21,247 current candidates and recipients of kidney, pancreas and simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplants. We analyzed data from all of these donors, candidates, and recipients.

Results

Mean waiting times for organ allocation of each priority differed significantly (2nd priority group, 1,701±974 days; 3rd priority group, 1,316±927 days; 4th priority group, 2,077±1,207 days). Additionally, HOPO candidates/deceased donor ratios were very different from each other (maximum, 49; minimum, 0.6). The number of deceased donors in region 1, 2, and 3 were 1,623, 429, and 603, respectively, while the number of transplantations in each region was 3,095, 597, and 1,165, respectively. The candidates registered at region 1 HOPO moved the longest distances on average for transplantation, and this value differed significantly different from that of other regions (56.18±91.9 km vs. 24.66±28.0 km vs. 26.20±37.3 km, P<0.05).

Conclusions

The incentive system of current allocation system for deceased donor kidney in Korea does not coincide with the purpose of the ‘Declaration of Istanbul’ and unnecessary social costs have occurred. Therefore, we should make an effort to change our current allocation system to the geographic sequence of organ allocation system.

Figures and Tables

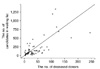

| Fig. 1The scatter plot of the number of deceased donors versus the number of patients in waiting list at each hospital-based organ procurement organization (HOPO). The HOPOs below the reference line may have a tendency to maintain current organ allocation system. However, the HOPOs above the reference line may have a tendency to change current organ allocation system. |

References

1. Min SI, Ahn SH, Cho WH, Ahn C, Kim SI, Ha J. Optimal system for deceased organ donation and procurement in Korea. J Korean Soc Transplant. 2011; 25:1–7.

2. Korean Network for Organ Sharing (KONOS). Annual data report [Internet]. Seoul: KONOS;c2014. cited 2017 Aug 24. Available from: https://www.konos.go.kr/konosis/common/bizlogic.jsp.

3. Steering Committee of the Istanbul Summit. Organ trafficking and transplant tourism and commercialism: the Declaration of Istanbul. Lancet. 2008; 372:5–6.

4. Kim MG, Jeong JC, Cho EJ, Huh KH, Yang J, Byeon NI, et al. Operational and regulatory system requirements for pursuing self-sufficiency in deceased donor organ transplantation program in Korea. J Korean Soc Transplant. 2010; 24:147–158.

5. United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). OPTN/SRTR annual report [Internet]. Richmond: UNOS;c2015. cited 2017 Aug 24. Available from: http://www.unos.org.

6. Statistics Korea. Regional population and population density [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea;c1996. cited 2017 Aug 24. Available from: http://www.index.go.kr/potal/main/EachDtlPageDetail.do?idx_cd=1007.

7. Lee JM, Lee YJ, Kyung KD, Im YC, Oh CK, Ahn JH, et al. Clinical analysis of 10 years brain death donors in single center after Korean Network for Organ Sharing. J Korean Soc Transplant. 2010; 24:196–203.

8. Lee SH, Huh KH, Lee HS, Kim HJ, Kim MS, Joo DJ, et al. Waiting time for deceased donor kidney allocation in Korea: a single center experience. J Korean Soc Transplant. 2012; 26:32–37.

9. Eurotransplant International Foundation. Eurotransplant manual version 3.0 [Internet]. Leiden: Eurotransplant International Foundation;2013. cited 2017 Aug 24. Available from: http://www.eurotransplant.org/cms/mediaobject.php?file=Chapter4_thekidney7.pdf.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download