Abstract

Background

It is critical to differentiate heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) from disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in heparinized intensive care unit (ICU) patients with thrombocytopenia because the therapeutic approach differs based on the cause. We investigated the usefulness of PF4/heparin antibody tests in these patients.

Methods

A total of 127 heparinized ICU patients whose platelet counts were <150×109/L or reduced by >50% after 5-10 days of heparin therapy were enrolled. PF4/heparin antibodies were measured using 2 immunoassays. We assessed the probability of HIT by using Warkentin's 4T's scoring system for antibody positive patients and compared routinely performed coagulation test results between patients with and without antibodies to evaluate the ability of these tests to discriminate between HIT and DIC.

Results

Positive results were obtained for 14 (11.0%) and 11 (8.7%) patients in the 2 assays. The analysis performed using the 4T's scoring system revealed that 11 of 20 (15.7%) patients with antibodies in at least 1 assay had intermediate or greater probability of HIT. Patients without antibodies had significantly higher levels of D-dimer than those with antibodies. However, there were no intergroup differences in platelet counts, PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, DIC score, and rate of overt DIC.

Conclusion

Seropositivity for PF4/heparin antibody was 8.7-11.0% in the patients with thrombocytopenia, and more than a half of them had an increased probability of HIT. Among the routine coagulation tests, only D-dimer was informative for differentiating HIT from DIC. PF4/heparin antibody test is useful to ensure appropriate treatment for thrombocytopenic heparinized ICU patients.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) occurs commonly in patients receiving heparin and it results in serious complications, including thrombocytopenia and thrombosis. HIT involves the immune-mediated formation of IgG antibodies against heparin/platelet factor 4 (PF4) complexes bound to platelets. These antibodies can bind to the platelet FcγIIa receptor, activate platelets, and induce thrombin formation and endothelial damage. As a result, both thrombocytopenia and thrombosis may develop [1-5]. Because ICU patients are frequently hospitalized long-term and many of them are post-operative, they are at high risk for venous thrombosis. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends heparin prophylaxis to reduce the risk of thrombosis in ICU patients [6]. When both thrombocytopenia and thrombosis develop in ICU patients receiving heparin, it is critical to differentiate between HIT and DIC to ensure proper treatment [1].

The likelihood of HIT can be evaluated clinically using the Warkentin pretest scoring system, known as the "4T's" [7-9]. This scoring system allows classification of patients into low (LR), intermediate (IR), and high risk (HR) groups by evaluating 4 parameters, including the severity and timing of thrombocytopenia, thrombosis or other findings, such as skin lesions, and presence of other causes of thrombocytopenia (Table 1). This system enables clinicians to assess the probability of HIT before laboratory testing. However, immunological detection of anti-PF4/heparin complex antibodies in the patient's serum or confirmation of platelet activation in normal serum after the patient's serum is added is also important to confirm the diagnosis of HIT [10]. The gold standard for the diagnosis of HIT is the serotonin release assay (SRA), a radioimmunoassay that evaluates the amount of serotonin released when platelets are activated. However, this method is not routinely performed because of radiation hazards and technical difficulties. Heparin-induced platelet aggregation (HIPA) using an aggregometer is frequently used as a functional assay. However, a lack of inter-laboratory standardization and poor reproducibility are disadvantages of this method. Therefore, many clinical laboratories use simple immunological detection of antibodies against the PF4/heparin complex for the diagnosis of HIT [9-12]. Because immunoassays are relatively easy to standardize and can provide rapid results, several test kits have been developed. To date, no comprehensive study, only several case reports, estimating the seropositivity of PF4/Heparin antibody using immunoassay has been published in Korea, in particular regarding ICU patients in Korea who are receiving heparin prophylaxis.

Therefore, we have analyzed PF4/Heparin antibody seropositivity in thrombocytopenic ICU patients during heparin prophylaxis. To our knowledge, this is the first study in Korea to assess ICU patients for PF4/heparin antibody seropositivity and to estimate the probability of HIT in patients with antibody in order to evaluate the usefulness of the anti-PF4/Heparin antibody test.

A total of 127 ICU patients treated with heparin prophylaxis whose platelet counts were <150×109/L and/or were reduced by more than 50% at 5-10 days after initiation of heparin therapy from January 2011 to May 2011 were enrolled in this study. All patients and/or family members received informed consent about this study from the clinician. The plasma samples for the patients meeting the above conditions were collected and cryopreserved at -70℃ for retrospective analysis. The samples were thawed at the time of the test. Two kinds of immunoassay for the detection of anti-PF4/heparin antibody (IgG, IgA, and IgM), Asserachrom HPIA (Diagnostica Stago, Asnières, France) and HemosIL HIT-Ab (Instrumentation Laboratory, Milan, Italy) assay, were performed simultaneously for each sample. These 2 immunoassays were performed according to the manufacturers' instructions. Based on the manufacturers' recommendations, cutoff values for the determination of a positive result were defined as an optical density of 0.304 for the Asserachrom HPIA assay and a level of 1 U/mL for the HemosIL HIT-Ab assay. No samples were duplicated, and positivity was not confirmed by a repeat test. The seropositivity of anti-PF4/Heparin antibody was determined according to these results, and the clinical likelihood of HIT was evaluated using Warkentin 4T's scoring system for patients with antibody in at least 1 of the 2 assays.

Five commonly used coagulation tests - platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), D-dimer, and fibrinogen level - were performed in all the enrolled patients. For PT and aPTT, Thromborel S (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, GmbH, Marburg, Germany) and Dade Actin FSL Activated PTT Reagent (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) were used as reagents, respectively. For fibrinogen and D-dimer, Dade Thrombin Reagent (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) and INNOVANCE D-dimer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) were used as reagents. All the tests were performed using an automatic coagulation analyzer (Sysmex CA-7000, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics). Using these data, the DIC score was calculated according to the DIC scoring system (Table 2) suggested by International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) in 2001 [13]. Additionally, the rate of overt DIC, which was defined as DIC score ≥5, was analyzed. Based on all data, results of investigated parameters (platelet counts, PT, aPTT, D-dimer, fibrinogen, DIC score, and the percentage of overt DIC) were compared between patients with antibody in at least 1 of the 2 assays and those without antibody to evaluate the usefulness of these tests as criteria to discriminate between DIC and HIT.

The Mann-Whitney U test was performed for the comparison of platelet counts, PT, aPTT, D-dimer, fibrinogen, and DIC score between patients with PF4/heparin antibody and those without antibody. The Chi-square test was performed for the comparison of the percentage of overt DIC between patients with antibody and those without antibody. For all analyses, tests were two-tailed, and P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed using SPSS 13.0.1 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

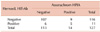

Among a total of 127 patients, 14 (11.0%) and 11 (8.7%) showed positivity in Asserachrom HPIA and HemosIL HITAb assays, respectively. The concordance rate between these 2 assays was 88.2%. Five (3.9%) patients showed positivity in both assays, and 20 (15.7%) patients showed positivity in at least 1 of the 2 assays. Among the 20 patients with antibody positivity in at least 1 of the 2 assays, 11 (55.0%) were categorized as intermediate of high risk for HIT based on scores of ≥4 by Warkentin 4T's scoring system (Table 3).

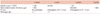

Patients without PF4/heparin antibody showed significantly higher median D-dimer levels than those with antibody in at least 1 of the 2 assays (4.17×103 vs. 2.45×103 µg/L, P=0.016). However, there were no significant differences in median platelet counts (56.0 vs. 62.5×109/L, P=0.460), median PT (15.2 vs. 14.4 sec, P=0.853), aPTT (40.7 vs. 42.1 sec, P=0.789), fibrinogen (2.62 vs. 2.00 g/L, P=0.142), DIC score (4.0 vs. 3.5 scores, P=0.495), or the percentage of overt DIC (43.0% vs. 35.0%, P=0.506) between patients without antibody and those with antibody in at least 1 of the 2 assays (Table 4).

HIT can result in severe complications, including thrombosis, if it occurs in ICU patients in whom heparin is used as prophylaxis to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism. Therefore, early recognition of HIT is deemed essential. In cases where HIT is suspected, laboratory evaluation for the diagnosis of HIT should be initiated promptly. The Warkentin 4T's scoring system for the assessment of clinical likelihood of HIT has demonstrated a negative predictive value of 100%, so that when the score is less than 4, we can exclude the possibility of HIT. However, for the confirmation of HIT, the presence of PF4/heparin antibody should be demonstrated using immunological or functional assay, especially in patients with high scores using Warkentin's scoring system [1, 7-10]. Although they are regarded as more precise tests than the immunologic assay, functional assays such as SRA or HIPA are difficult to perform and require experienced laboratory technicians. Therefore, evaluation of serum PF4/heparin antibody levels using immunoassay is proposed as a practical and useful adjunct in clinical settings, because immunoassay permits high throughput within a limited time.

Previous studies have reported that PF4/heparin antibody testing is a reliable strategy to rule out the diagnosis of HIT when combined with the Warkentin 4T's scoring system results. However, the risk of false positivity in PF4/heparin antibody testing limits its efficacy. Therefore, a functional assay such as SRA or HIPA is thought to be necessary to confirm HIT in antibody positive patients [1, 14, 15]. In our study, because the Warkentin 4T's scoring system was only applied to patients in the study population who were antibody positive, the confirmation of the usefulness of the PF4/heparin antibody test may be limited. However, our results have demonstrated that more than a half of the patients with antibody in at least 1 of 2 assays had a clinically "same or more than IR" of HIT. This implies that in some cases, PF4/heparin antibody tests may be useful not only for the exclusion, but also for the diagnosis of HIT.

The seropositivity of PF4/heparin antibody can vary according to the clinical settings. Previous studies have reported seropositivity rates of 14.3% and 13.6% in 755 heparinized patients and 59 ICU patients undergoing heparin prophylaxis, respectively. In the latter result, the clinical setting was same as that in our study [14, 15]. In Korea, a study on 338 patients with acute coronary syndrome receiving unfractionated heparin reported an incidence of HIT as 11.8% [16]. However, this study diagnosed HIT based on clinical information, not on the immunological detection of PF4/heparin antibody. As previously mentioned, to date, no studies, other than case reports, regarding seropositivity of PF4/heparin antibody using immunoassay have been published. [17, 18]. Our study analyzed seropositivity of PF4/heparin antibody in 127 ICU patients who were receiving heparin by 2 kinds of immunoassays. Our results demonstrated a seropositivity rate for PF4/heparin antibody of 8.7-11.0%, which is similar to the finding of 13.6% in the previous study performed in same clinical setting mentioned above [14]. Our study is the first study, which evaluated the seropositivity of PF4/heparin antibody in ICU patients in Korea.

If an ICU patient receiving heparin develops both thrombocytopenia and clinical signs of thrombosis, the most important aspect to provide appropriate management is the differentiation between DIC and HIT. Both have similar clinical profiles, but require totally different therapeutic approaches. Currently, many clinicians evaluate patients for DIC using coagulation tests such as PT/aPTT, fibrinogen, and D-dimer and subsequently calculating the DIC score suggested by ISTH 2001 criteria [13]. Our results showed that only D-dimer was significantly different between patients with antibody and those without antibody. This indicates that the most commonly performed coagulation tests are of limited value for differentiating between DIC and HIT. Therefore, it is proposed that the PF4/heparin antibody test should be performed for the diagnosis of HIT in thrombocytopenic ICU patients receiving heparin.

There are limitations in our study. First, as mentioned, we did not evaluate the clinical possibility of HIT for all the patients using the 4T's system. This may have influenced our evaluation on the usefulness of the PF4/heparin antibody test. Second, we did not compare PF4/heparin antibody test results with results from standard methods such as SRA or HIPA due to technical reasons. Further studies eliminating these limitations should be required in the future.

In conclusion, the seropositivity for anti-PF4/heparin antibody was 8.7-11.0% in heparin-treated ICU patients with thrombocytopenia, and more than a half of them had increased probability of HIT by 4Ts score. Among the routine coagulation tests, only D-dimer was informative for discriminating HIT from DIC. Anti-PF4/heparin antibody test should be performed in thrombocytopenic ICU patients receiving heparin in order to provide the appropriate treatment.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

The Warkentin 4T's scoring system to estimate the probability of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Table 3

The results of 2 ELISA tests for detecting anti-PF4/heparin antibodies in 127 heparin-treated ICU patients with thrombocytopenic events.

Table 4

Comparison of platelet count, PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer, and DIC scores between patients with and without anti-PF4/heparin antibodies.

P-values obtained from Mann-Whitney U testa) and Chi-Square testb).

c)Anti-PF4/heparin antibody was defined as negative when all the results of the 2 assays were within the Cutoff values (optical density of 0.304 for Asserachrom HPIA and 1U/mL for HemosIL HIT-Ab based on the manufacturer's recommendations) and was defined as positive when at least one of the 2 results was beyond the cutoff values.

Abbreviations: PT, prothrombin time; aPTT, activated partial prothrombin time; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; PF4, platelet factor 4.

References

1. Denys B, Stove V, Philippé J, Devreese K. A clinical-laboratory approach contributing to a rapid and reliable diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Thromb Res. 2008. 123:137–145.

2. Warkentin TE. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: pathogenesis and management. Br J Haematol. 2003. 121:535–555.

5. Greinacher A, Warkentin TE. Recognition, treatment, and prevention of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: review and update. Thromb Res. 2006. 118:165–176.

6. Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008. 133:6 Suppl. 381S–453S.

7. Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007. 83:575–582.

8. Lo GK, Juhl D, Warkentin TE, Sigouin CS, Eichler P, Greinacher A. Evaluation of pretest clinical score (4 T's) for the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in two clinical settings. J Thromb Haemost. 2006. 4:759–765.

9. Warkentin TE, Sheppard JA. Testing for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia antibodies. Transfus Med Rev. 2006. 20:259–272.

10. Warkentin TE. New approaches to the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Chest. 2005. 127:2 Suppl. 35S–45S.

11. Arepally G, Reynolds C, Tomaski A, et al. Comparison of PF4/heparin ELISA assay with the 14C-serotonin release assay in the diagnosis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995. 104:648–654.

12. Janatpour KA, Gosselin RC, Dager WE, et al. Usefulness of optical density values from heparin-platelet factor 4 antibody testing and probability scoring models to diagnose heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007. 127:429–433.

13. Taylor FB Jr, Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M. Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001. 86:1327–1330.

14. Avidan MS, Smith JR, Skrupky LP, et al. The occurrence of antibodies to heparin-platelet factor 4 in cardiac and thoracic surgical patients receiving desirudin or heparin for postoperative venous thrombosis prophylaxis. Thromb Res. 2011. 128:524–529.

15. Juhl D, Eichler P, Lubenow N, Strobel U, Wessel A, Greinacher A. Incidence and clinical significance of anti-PF4/heparin antibodies of the IgG, IgM, and IgA class in 755 consecutive patient samples referred for diagnostic testing for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Eur J Haematol. 2006. 76:420–426.

16. Kim MJ, Kim YJ, Kim JG, et al. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) in patients with acute coronary syndrome: incidence and clinical feature, retrospective study. Korean J Hematol. 2005. 40:28–33.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download