Abstract

Splenic infarction is most commonly caused by cardiovascular thromboembolism; however, splenic infarction can also occur in hematologic diseases, including sickle cell disease, hereditary spherocytosis, chronic myeloproliferative disease, leukemia, and lymphoma. Although 10% of splenic infarction is caused by hematologic diseases, it seldom accompanies autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). We report a case of a 47-year-old woman with iron deficiency anemia who presented with pain in the left upper abdominal quadrant, and was diagnosed with AIHA and splenic infarction. Protein C activity and antigen decreased to 44.0% (60-140%) and 42.0% (65-140%), respectively. Laboratory testing confirmed no clinical cause for protein C deficiency, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, sepsis, hepatic dysfunction, or acute respiratory distress syndrome. Protein C deficiency with splenic infarction has been reported in patients with viral infection, hereditary spherocytosis, and leukemia. This is a rare case of splenic infarction and transient protein C deficiency in a patient with AIHA.

Go to :

Splenic infarction can occur in various diseases; however, the incidence is very low. Thromboembolic events associated with atrial fibrillation, cardiac surgery, or infective endocarditis are well-known causes of splenic infarction. Additionally, several hematologic diseases including sickle cell anemia, lymphoma, and leukemia can cause splenic infarction [1]. Chronic myeloproliferative disease can also lead to splenic infarction due to massive splenomegaly and a hypercoagulable state [1]. Massive splenomegaly may lead to splenic infarction and subsequent splenic rupture.

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), caused by autoantibodies binding to the surface of RBCs, is an uncommon disease with an incidence of approximately 1-3 cases/100,000 per year in the general population [2]. In AIHA, massive hemolysis causes activation of the immune response, destruction of RBCs, and splenomegaly [3]. Splenic infarction can occur in AIHA, although rarely, and only 2 cases have been reported worldwide [4, 5].

Deficiencies of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin are well-known risk factors for thromboembolism. Hereditary protein C deficiency carries an approximately 10-fold increased risk for venous thrombosis [6]. There have been many reports of splenic infarction in patients with protein C deficiency [7, 8], and a few of them were accompanied by hematologic diseases, such as hereditary spherocytosis or acute myeloid leukemia [7, 9].

Although 2 case of splenic infarction with AIHA have been reported, neither was accompanied by transient protein C deficiency. In this report, we present a rare case of splenic infarction and transient protein C deficiency, which occurred in a patient with AIHA.

Go to :

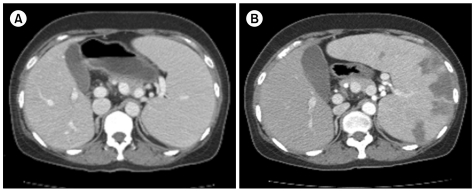

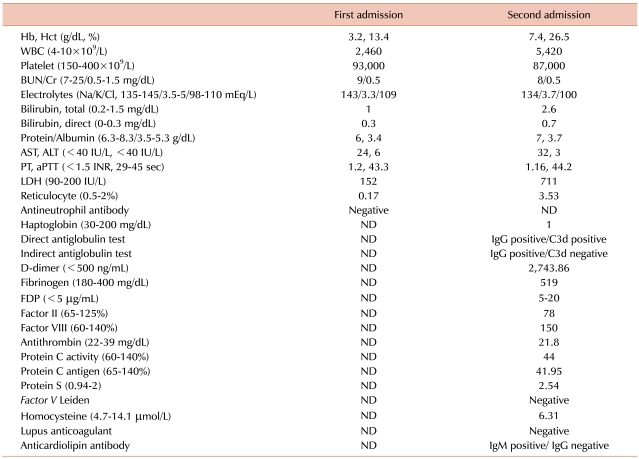

A 47-year-old woman visited our emergency room (ER) because of a persistent headache, chills, acute cough, and a mild fever for 5 days. Initial examination showed: blood pressure, 114/59 mmHg; body temperature, 37.7℃; pulse rate, 102/min; and breathing rate, 20/min. She appeared pale and chronically ill. On physical examination, there was no specific finding except a palpable spleen in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) of the abdomen. She had no notable previous medical history except iron deficiency anemia (IDA) due to severe menorrhagia, for which she took iron supplements for 6 months. Chest X-ray showed mild cardiomegaly, and her EKG was normal. The blood tests showed: Hb, 3.2 g/dL; Hct, 13.4%; WBCs, 2.4×109/L; platelets (PLTs), 93×109/L; RDW, 21.3%; MCV, 57.3 fL; MCH, 13.7 pg; reticulocytes, 0.17%; and LDH, 152 IU/L. Iron profiling showed a serum ferritin level of 3 ng/mL, a serum iron level of 22 µg/dL, and a UIBC of 325 µg/dL. After 2 packs of RBCs were transfused in the ER, her Hb increased to 6.3 g/dL, and her general condition improved. She was admitted to our hospital for further examination and treatment. Peripheral blood (PB) smear showed microcytic hypochromic dysmorphic RBCs, including many elliptocytes, schistocytes, and teardrop cells. Biochemical tests found: total billirubin, 1 mg/dL; indirect bilirubin, 0.3 mg/dL; AST, 24 IU/dL; ALT, 6 IU/dL; BUN, 9 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.5 mg/dL; Na, 143 mEq/L; K, 3.3 mEq/L; and Cl, 109 mEq/L (Table 1). Two blood cultures showed no microorganism growth for 5 days. Serological testing for Parvovirus was positive for IgG and negative for IgM. Tests for antinuclear antibody (ANA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) were negative. The stool occult blood test was negative, and there was no evidence of blood loss except hypermenorrhea. Abdominal CT was performed to rule out gastrointestinal malignancy. Abdominal CT showed that spleen was enlarged to approximately 17 cm in length of the long axis (Fig. 1). A bone marrow biopsy was performed to find other causes for pancytopenia and iron-refractory IDA. Bone marrow aspiration showed hypercellular marrow with an increased M:E ratio (0.7:1). The cellularity of the bone marrow was up to 80%. Both erythropoiesis and the number of megakaryocytes increased. However, iron storage decreased. There were no dysplastic marrow cells or abnormal cell infiltration. On the 12th hospital day, the patient was discharged with the Hb level of 7.2 g/dL.

Five days later, the patient revisited the ER due to severe abdominal pain in the LUQ. She suffered from acute abdominal pain after she was discharged, and the pain was aggravated. Her blood pressure was 160/80 mmHg, pulse rate was 120/min, and breathing rate was 30/min. She was not febrile. Physical examination showed that she had direct tenderness in the left upper abdomen. Blood tests revealed: Hb, 7.4 g/dL; Hct, 26.5%; WBC, 5.4×109/L; PLTs, 87×109/L; MCV, 73.4 fL; and MCH, 20.5 pg. These were nearly identical as those at first admittance. However, LDH increased to 711 IU/L from 152 IU/L, and reticulocytes increased to 3.53% from 0.17%. Biochemical testing showed: total billirubin, 2.6 mg/dL; indirect billirubin, 0.7 mg/dL; AST, 32 IU/L; and ALT, 3 IU/L (Table 1). Both PT and aPTT were within the normal range. A PB smear showed normocytic normochromic RBCs with spherocytes, elliptocytes, and teardrop cells. Haptoglobin decreased to 1 mg/dL (30-200 mg/dL) and D-dimer increased to 2,743 ng/mL (0-500 ng/mL). Under suspicion of hemolytic anemia, direct antiglobulin tests (DAT) and indirect antiglobulin tests (IAT) were performed. The DAT for IgG and C3d and the IAT for IgG were positive, but the IAT for C3d was negative. Flow cytometry for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) was within the normal range. She was diagnosed with AIHA. EKG showed sinus tachycardia. Abdominal CT showed that the spleen had increased to 20 cm and new multiple splenic infarctions were observed compared with the previous CT. However, thrombosis of blood vessels, including the splenic artery, was not observed (Fig. 1). Transthoracic echocardiography showed no intracardiac vegetation or thrombus.

To rule out a hypercoagulable status, the activity of protein C and S and antigen level were measured. Protein C activity and antigen level decreased to 44.0% (60-140%) and 42.0% (65-140%), respectively, and protein S activity and antigen level were within the normal range. Antithrombin was within the normal range at 21.8 mg/dL (22-39 mg/dL). No Factor V Leiden mutation or lupus anticoagulant antibody was present. Anticardiolipin antibody IgG was negative, but IgM was positive. Serologic tests for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, and hepatitis B and C virus were performed. Anti-EBV viral capsid IgM (anti-EBV-VCA IgM) was equivocal, and all others were negative. Anti EBV-VCA IgG was negative, and EBNA was not checked.

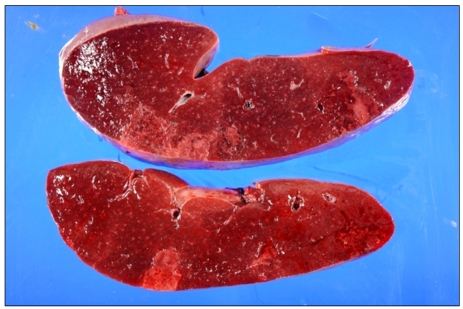

On the second hospital day, a splenectomy was performed due to the uncontrolled, severe left upper abdominal pain. On the cross section, the spleen showed multifocal wedge-shaped subcapsular infarcts. On microscopic examination, there was no evidence of lymphoma or leukemic infiltration (Fig. 2). After splenectomy, her symptoms and pancytopenia improved. Two weeks later, complete blood counts showed a full recovery: Hb, 12.1 g/dL; WBCs, 6.9×109/L; PLTs, 629×109/L; and reticulocytes, 1.37%.

After discharge, her protein C activity was 109.0% (60-140%) and antigen level was 132% (65-140%). The patient has been under observation at the outpatient center.

Go to :

AIHA is a relatively uncommon disorder that leads to hemolysis due to autoantibodies against RBC membrane antigens. These autoantibodies can be confirmed by DAT and IAT. If intravascular hemolysis is present, schistocytes, microspherocytes, and elliptocytes are observed in the PB smear, and hemoglobin is detected in the plasma and urine. Both hemolysis and autoantibodies should be found for a diagnosis of AIHA. Splenic infarction is often associated with hemolytic diseases, including sickle hemoglobinopathies, myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, leukemia, and lymphoma. However, splenic infarction is rare in AIHA [1].

At first admission, we concluded that IDA was the only cause of anemia, even though the presence of hypercellular marrow and splenomegaly was sufficient to consider hemolytic anemia. Prolonged IDA might have suppressed hemolysis, because the number of RBCs was decreased in the PB and RBC maturation was impaired in bone marrow. After transfusion and iron supplementation, hemolysis was triggered and accelerated. Massive hemolysis occurred and splenomegaly was aggravated due to the overload. Finally, the spleen was infracted and she returned to the hospital again.

The most common cause of splenic infarction is cardiovascular thromboembolism, accounting for 22% of cases. Thrombophilia, such as protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, antithrombin deficiency, antiphospholipid syndrome, hyperhomocysteinemia, and factor V Leiden mutation, is the second most common cause of splenic infarction. The third most common cause is hematologic diseases, including sickle hemoglobinopathies, myelofibrosis, PNH, polycythemia vera, leukemia, and lymphoma, which account for 10% of splenic infarctions [1]. In cardiovascular thromboembolism or thrombophilia, splenic infarction occurs with multiple embolic events involving the lung, kidney, heart, and intestine. However, in hematologic diseases, splenic infarction is generally limited to the spleen. Therefore, the mechanism of splenic infarction in hematologic malignancy differs from that in cardiovascular thromboembolism or thrombophilia.

Protein C is a vitamin K-dependent protein synthesized in the liver that circulates as an inactivated form in the blood stream. It is activated by binding to thrombin, and then it reduces the coagulation activity of factor Va and VIIIa. Because protein C has a crucial function in coagulation, protein C deficiency increases the risk of thrombosis. Hereditary protein C deficiency is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Acquired protein C deficiency is seen in patients with liver diseases, severe infections, septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [7]. Protein C deficiency has also been reported in some hematologic diseases, such as AML and hereditary spherocytosis [7, 9, 10]. In active AML patients, protein C level and activity were lower than those in normal control individuals or cured AML patients [10]. In one patient with AML who presented with multiple infarctions of the spleen, kidney, and intestine, protein C level was transiently decreased during induction chemotherapy, but was normalized after complete remission was achieved [7]. In hematologic diseases, protein C deficiency can occur asymptomatically and transiently, even without evidence of DIC, liver disease, sepsis, or ARDS [7]. It is unclear whether transient protein C deficiency increased the risk of a subsequent thromboembolic event in hematologic diseases.

In our case, the patient had no liver disease, severe infection, sepsis, or ARDS, and did not have a DIC condition. Antithrombin was mildly decreased; however, PT, aPTT, and fibrinogen were within the normal range. Although D-dimer was elevated, the test is nonspecific, and it can be increased in many conditions, including immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. Although PLTs were slightly reduced (87×109/L), thrombocytopenia might result from splenic sequestration and severe BM suppression rather than DIC. There was no evidence that she had severe infection or sepsis.

There have been a few reports on splenic infarction associated with viral infections such as CMV or EBV [9, 11-13]. In acute viral infection, antiphospholipid antibody is transiently induced and contributes to the outbreak of thromboembolism in multiple organs [12, 14]. Another proposed cause of splenic infarction in viral infection is that the spleen becomes hypertrophied to remove EBV-infected B cells, and thus becomes relatively hypoxic [11].

Based on the present case, some possible mechanisms for splenic infarction in patients with hemolytic anemia can be proposed. Firstly, the sudden blood transfusion and iron supplementation triggered hemolysis, and the spleen was overloaded. The size of spleen quickly increased, which could have led to breakage of blood vessels and the parenchyma of the spleen. Secondly, the spleen could have been vulnerable to hypoxic injury, because it was already in a prolonged anemic condition. Thirdly, the transient decreases in protein C activity and antigen could have contributed to a thromboembolic tendency in the microvasculature of the spleen. Fourthly, massive hemolysis facilitated release of procoagulant and/or alteration of erythrocyte morphology [15]. This could have caused a further increase in thrombosis. The final possible cause is a hidden viral infection that aggravates the hemolytic anemia and induces proliferation of infected cells. The patient's initial presentations were headache and fever; but, there was no evidence of bacterial infection. Her symptoms were self-limiting and did not require antimicrobial treatment. Anti EBV-VCA IgM was equivocally positive, IgG was negative, and EBNA was not checked. Although these findings are not fully compatible with active EBV infection, they also could not rule out viral infection. According to the literature, antiphospholipid antibody can be produced during viral infection. In this case, anticardiolipin IgM was positive, but IgG was negative. Hidden viral infections, such as EBV infection, might be accompanied by AIHA, and could aggravate the hemolysis in AIHA.

Splenectomy was inevitable due to the severe, intolerable pain in the left upper abdomen. According to the literature, splenic infarction may result in significant morbidity and mortality and requires immediate diagnosis and treatment [1]. Therefore, it is important to immediately recognize splenic infarction in patients with predisposing diseases.

We report a patient with AIHA, splenic infarction, and transient protein C deficiency, who was misdiagnosed as having IDA at first admission. Further examination of possible hemolytic anemia is recommended, if splenomegaly and/or abnormal PB findings are present in patients with hypochromic microcytic anemia.

Go to :

References

1. Antopolsky M, Hiller N, Salameh S, Goldshtein B, Stalnikowicz R. Splenic infarction: 10 years of experience. Am J Emerg Med. 2009; 27:262–265. PMID: 19328367.

2. Naithani R, Agrawal N, Mahapatra M, Pati H, Kumar R, Choudhary VP. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in India: clinico-hematological spectrum of 79 cases. Hematology. 2006; 11:73–76. PMID: 16522555.

3. Eichner ER. Splenic function: normal, too much and too little. Am J Med. 1979; 66:311–320. PMID: 371397.

4. Horeau J, Robin C, Guenel J, Nicolas G. An unusual complication of acquired hemolytic anemia, splenic infarction. Concours Med. 1963; 85:663–666. PMID: 13961739.

5. Tzanck A, Andre R, Dreyfus B. Acquired hemolytic anemia with infarct of the spleen; splenectomy; recovery. Bull Mem Soc Med Hop Paris. 1951; 67:286–290. PMID: 14831012.

6. Khor B, Van Cott EM. Laboratory tests for protein C deficiency. Am J Hematol. 2010; 85:440–442. PMID: 20309856.

7. Farah RA, Jalkh KS, Farhat HZ, Sayad PE, Kadri AM. Acquired protein C deficiency in a child with acute myelogenous leukemia, splenic, renal, and intestinal infarction. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2011; 22:140–143. PMID: 21178585.

8. Olson JF, Steuber CP, Hawkins E, Mahoney DH Jr. Functional deficiency of protein C associated with mesenteric venous thrombosis and splenic infarction. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1991; 13:168–171. PMID: 2069226.

9. Breuer C, Janssen G, Laws HJ, et al. Splenic infarction in a patient hereditary spherocytosis, protein C deficiency and acute infectious mononucleosis. Eur J Pediatr. 2008; 167:1449–1452. PMID: 18604554.

10. Troy K, Essex D, Rand J, Lema M, Cuttner J. Protein C and S levels in acute leukemia. Am J Hematol. 1991; 37:159–162. PMID: 1830452.

11. Suzuki Y, Shichishima T, Mukae M, et al. Splenic infarction after Epstein-Barr virus infection in a patient with hereditary spherocytosis. Int J Hematol. 2007; 85:380–383. PMID: 17562611.

12. van Hal S, Senanayake S, Hardiman R. Splenic infarction due to transient antiphospholipid antibodies induced by acute Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Clin Virol. 2005; 32:245–247. PMID: 15722031.

13. Justo D, Finn T, Atzmony L, Guy N, Steinvil A. Thrombosis associated with acute cytomegalovirus infection: a meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2011; 22:195–199. PMID: 21402253.

14. Fiehn C, Pezzutto A, Hunstein W. Superficial migratory thrombophlebitis in a patient with reversible protein C deficiency and anticardiolipin antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994; 53:843–844. PMID: 7864700.

15. Ghanayem BI, Long PH, Ward SM, Chanas B, Nyska M, Nyska A. Hemolytic anemia, thrombosis, and infarction in male and female F344 rats following gavage exposure to 2-butoxyethanol. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2001; 53:97–105. PMID: 11484844.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download