Abstract

Background

Reports of indeterminate lupus anticoagulant (LAC) results are common; however, no published data on their prevalence or clinical significance are available. We investigated the prevalence and clinical characteristics of patients with indeterminate LAC.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical and serologic characteristics of 256 unselected patients with LAC results.

Results

Indeterminate results were observed in 32.7% of LAC profiles that were least frequent (25.4%) when activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was normal, most frequent (39.8%) when aPTT was elevated, and were observed in 35% of patients taking warfarin. The final indeterminate LAC cohort included 65 patients with a mean follow-up of 18 months. Malignancy and autoimmune disease were present in 29% and 25% of patients, respectively. The most common thrombotic events were deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (28%), cerebral ischemic stroke (14%) and pulmonary embolism (14%). Patients with indeterminate results were more likely to be men, older, and with a history of DVT, superficial thrombosis, or myocardial infarction than patients with negative tests (N=106). Concurrent warfarin therapy was more prevalent in the indeterminate group, but was not statistically significant. In the multivariate analysis, none of the variables showed statistical significance. During follow-up, 10 of 16 patients with indeterminate results showed change in classification upon retesting.

Go to :

Antiphospholipid (aPL) antibodies are a group of heterogeneous autoantibodies against phospholipid (PL)-bound proteins. Conley and Hartman [1] first described circulating anticoagulants in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in 1952. The term, lupus anticoagulant (LAC), was first used by Feinstein and Rapaport [2] in 1972 to describe antibodies that inhibited PL-D coagulation in vitro. The term "LAC assay" is a double misnomer, because it is neither a test for lupus nor a test for a natural anticoagulant. In fact, the various "LAC assays" are tests that detect immunoglobulins against PL-binding proteins that inhibit coagulation in vitro, but are clinically associated with thrombosis.

LAC is a well-established risk factor for thrombosis [3, 4]. The International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH) criteria for the diagnosis of LAC include the followings: a screening test that demonstrates prolongation of PL-D clotting time; a mixing test that confirms the presence of an inhibitor; confirmation that the inhibitor is PL-D; and the exclusion of other coagulopathies [5]. These criteria were recently updated by the ISTH to clarify the acceptable test types and the interpretation of cut-off values [6]. Most published epidemiologic studies investigating the clinical associations of LAC with thrombosis have only included cases meeting all 4 laboratory diagnostic criteria. However, since LAC testing includes screening tests, mixing studies, and phospholipid neutralization assays, not all test results will be concordant, and samples are not always clearly positive or negative for the presence of LAC. Patients with test results that fulfill some, but not all, of the criteria are often considered to show negative results for LAC. However, the prevalence of patients whose testing results fulfill some but not all ISTH criteria, a so-called "indeterminate LAC" result, and its clinical implications are still unclear.

We retrospectively studied one of the largest known cohorts of patients with indeterminate LAC results from a single referral center to determine the prevalence, clinical, and serologic features of this group.

Go to :

This study investigated the prevalence of thrombotic events in an initial cohort of unselected patients (N=256), who were tested for LAC and other aPL antibodies over a 2-month period from one tertiary hospital in the United States. The laboratory results of prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), dilute Russell's viper venom time (DRVVT), hexagonal phase PL neutralization (STACLOT, Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, NJ, USA), and platelet neutralization procedure (PNP) were evaluated in all patients. The profile included 3 screening assays (aPTT [Actin FSL, Siemens and STACLOT Screen] and DRVVT screen [Precision Biologic]), 2 mixing studies (aPTT 1:1 mix and DRVVT 1:1 mix), and 3 separate PL-D assays [DRVVT confirm, STACLOT, and PNP (Precision Biologic)]. Samples containing >0.1 U/mL heparin were pre-treated with Hepadsorb to neutralize heparin activity. The LAC profile was considered indeterminate, if 1 or more PL-D test results were positive, but the aPTT or DRVVT mixing study was negative.

The initial cohort included 256 patients, and 83 had indeterminate results. From this group, 18 patients were excluded: 4 due to incomplete data, 2 due to high heparin levels (anti-Xa >1.0 U/mL), 5 due to other prothrombotic etiologies, and 7 with other positive aPL antibodies (aCLs [anticardiolipin antibodies] or anti-β2 GPIs [anti-β2 glycoprotein I antibodies]). To assess their thrombotic history, we performed retrospective chart reviews and tabulated all the Sapporo clinical features, malignancies, and autoimmune disorders 5 years before and 2 years after the index laboratory testing. Events that did not fulfill diagnostic criteria for thrombosis, ischemic events, or obstetrical complications were excluded. The final analysis sample (after applying the exclusion criteria) included 65 patients with indeterminate LAC, 27 with positive LAC, and 106 negative for LAC.

A protocol form was used to record the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients. The information included demographic patient characteristics, disease-related data (underlying disease, site of thrombosis, associated clinical manifestations, and precipitating factors), family history, laboratory features, and the presence of inherited or acquired prothrombotic disorders. Standardized clinical and laboratory data collected on the protocol form were transferred to a designated computerized database (Excel/Microsoft).

Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad software 2005 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The Student's t test was used to compare mean values using a two-tailed analysis. Associations between categorical variables were tested using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test when required. Differences were considered statistically significant at when P <0.05.

Go to :

Among the final cohort of 65 patients with indeterminate LAC results, 30 (46%) were male and 35 (54%) were female. The median age was 57 years, with a mean±SD of 54.5±1.8 years. Active malignancy and myeloproliferative disorders were present in 19 patients (29%), and 16 (25%) had an underlying autoimmune disease. The most common autoimmune disease was SLE in 4 patients (6%). Patients in this group had a median follow-up of 22 months, with a mean of 18±12.8 months.

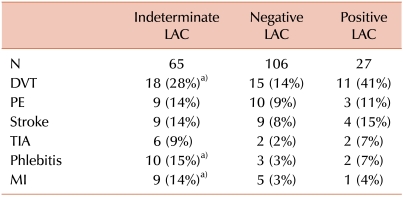

Of the 65 patients with indeterminate LAC results, 18 patients (28%) had a history of venous thrombosis, 16 (25%) had arterial thrombosis, and 3 (5%) had mixed arterial and venous thrombosis. The most common thrombotic event was deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in 18 patients (28%), followed by cerebral ischemic stroke and pulmonary embolism (PE) in 9 patients (14%) each, and transient ischemic attack (TIA) in 6 patients (9%). Other venous events were superficial thrombosis (ST) in 11 patients (17%), hepatic thrombosis in 1 patient (1.5%), and cerebral venous thrombosis in 1 patient (1.5%). A history of myocardial infarction (MI) was documented in 9 patients (14%) within 5 years from initial testing. Renal infarction was observed in 2 patients (3%), and ischemic colitis in 1 patient (1.5%). The most frequently associated nonthrombotic manifestations were hematological disorders, which were present in 6 patients (9%); the most frequent of these was thrombocytopenia in 4 patients (6%). One patient (1.5%) had toxemia, but no other obstetrical complications. Four patients (6%) in this group died: 1 due to PE and sepsis; 1 due to infective endocarditis; and 2 had no documented cause of death.

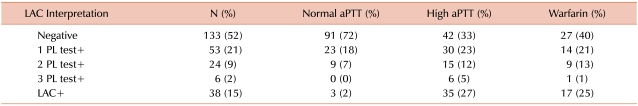

The unselected initial referred cohort included 256 patients, 2 of which were excluded due to high heparin levels. Before applying any other exclusion criteria, 32.7% of these patients had indeterminate results. Indeterminate results were least frequent (25.4%) when the aPTT was normal, most frequent (39.8%) when the aPTT was elevated, and were observed in 35% of patients taking warfarin. In the 53 patients with a single abnormal PL test, STACLOT was the most frequently abnormal test (28/53, 52.8%), followed by DRVVT (20/53, 37.7%), and PNP (5/53, 9.4%). These findings are summarized in Table 1.

In the initial group of patients with indeterminate results (N=83), aCLs or anti-β2 GPIs were detected in 7 patients (8%). Inherited prothrombotic disorders were found in 4 patients (5%), including heterozygosity for factor V Leiden (N=1) and heterozygosity for prothrombin G20210A (N=2). One patient had heparin induced thrombocytopenia syndrome (HIT).

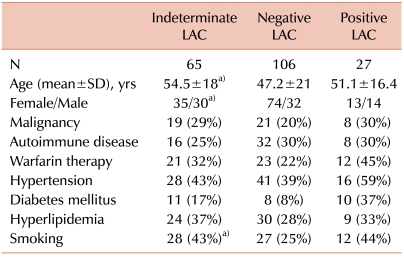

Comparison between patients with indeterminate LAC tests and those with negative results is summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Patients in the indeterminate group were relatively older (54.5±18 vs. 47.2±21 years), and this difference was statistically significant (P=0.02). These patients were also more likely to be male (P=0.049). History of DVT and ST of the extremities was significantly higher in the indeterminate group (P=0.04 and 0.005, respectively). History of MI was also significantly more prevalent in the indeterminate group (P=0.045). Concurrent oral anticoagulant therapy with warfarin was seen in 32% of patients in the indeterminate group compared to 22% of patients with negative results; however, it did not reach statistical significance (P=0.15). Although malignancies and immune disorders have been associated with aPL antibodies [7], there was no significant difference between the 2 groups (P=0.19 and 0.48, respectively). In the multivariate analysis model (age, gender, malignancy, immune disease, DVT, and warfarin therapy), none of the variables reached statistical significance between the indeterminate LAC and negative result groups. Comparing these clinical variables between patients with indeterminate results and those with positive LAC from the same cohort failed to show any significant differences.

Go to :

In 1983, Hughes first described patients with a combination of certain clinical features and aPL antibodies [8]. Multiple aPL antibodies have been identified since then; however, LAC is probably the strongest risk factor for thrombosis [4]. To establish a laboratory diagnosis of LAC, the test results must fulfill all of the abovementioned ISTH criteria, including a positive screening test, mixing studies, and phospholipid dependence. Patients with test panels that meet some, but not all criteria are considered indeterminate, and are usually not enrolled in epidemiological or therapeutic studies. This is the largest cohort of patients with indeterminate LAC results studied for clinical associations. To date, no previous studies have determined the prevalence of indeterminate LAC results and its clinical significance.

Indeterminate results were found to be common among patients referred for LAC evaluation, and were seen in 32.7% of all LAC profiles. Indeterminate results were most prevalent when the aPTT was elevated (39.8%) and in patients taking warfarin (37.5%). Accurate testing for LAC may be compromised by anticoagulant medications, including warfarin, possibly due to low factor X levels causing false positive results [9, 10]. For this reason, the revised guidelines for diagnosis of the aPL syndrome recommend postponing laboratory investigation until discontinuation of treatment [11]. Concurrent warfarin therapy was seen in 29% of patients with indeterminate results and in 20% of those with negative results; however, both before and after applying the exclusion criteria, there was no significant difference in prevalence of warfarin therapy between the 2 groups. Olteanu et al. [12] recently showed that warfarin does not interfere with LAC detection by DRVVT. Heparin contamination is also a common problem in the evaluation of LAC, especially at levels >1 anti-Xa U/mL. Although some DRVVT and other phospholipid reagents contain polybrene, which can neutralize heparin, additional neutralizing agents might be still needed for some assays that do not contain polybrene. Some types of low molecular weight heparin can interfere with LAC results at levels as low as 0.25 anti-Xa U/mL. Patients with anti-Xa levels >1.0 U/mL were excluded from the final analysis.

This high prevalence of indeterminate results might have some clinical implications. We speculated that patients with indeterminate results might represent a distinct clinical, serological, or prognostic entity compared to those with negative tests from the same referred cohort. Patients in the indeterminate group were older, with mean age of 54.5 years (vs. 47.2 years in the negative group, P=0.021). Although aPL antibodies were found among young, healthy, asymptomatic subjects, the prevalence of these antibodies, including LAC, increased with age [13]. This higher prevalence could be also related to the common coexistence of chronic diseases in the older age group. Patients in the indeterminate group were more likely to be male. This differed from the very high percentage of female patients in the negative group. Female patients are more likely to be referred for LAC testing due to gynecological concerns or non-specific rheumatologic symptoms; thus, it is not unexpected to see a higher proportion of women in the negative group. Regarding the Sapporo clinical criteria, DVT of the extremities was significantly higher in the indeterminate group (P=0.044). LAC has been linked to lower extremity DVT both separately and in combination with other aPL antibodies. However, this association is still open for debate. De Groot et al. [14] showed that the presence of LAC, anti-β2 GPI antibodies, and antiprothrombin antibodies were risk factors for DVT in the general population. The strongest association was observed with the presence of a combination of LAC and anti-β2 GPI or antiprothrombin antibodies. In contrast, Sidelmann et al. [15] suggested that concurrent inflammation and a DVT episode might be the cause of such a high prevalence of LAC in these patients. One interesting clinical observation in our cohort is the statistically significant prevalence of superficial thrombophlebitis (ST) in the indeterminate group (P=0.005). In spite of its statistical significance, we do not think this observation has much clinical significance for several reasons. First, because ST is not included in the Sapporo criteria, reporting in this study was not limited to 5 years from the initial testing. Second, ST was poorly documented in the medical records, without documentation of instrumentation or DVT, specific time of the event, site, or number of episodes. Third, this might represent an association with DVT in this group [16], rather than an independent association with indeterminate LAC. The prevalence of obstetrical complications was very low in all 3 groups, mainly because the study center is not a large obstetrical referral center.

Different aPL antibodies have also been associated with malignancies [7] and immune mediated disorders like connective tissue disorders, vasculitis [17], and inflammatory bowel disorders [18]. We speculated that indeterminate LAC results might be associated with such disorders. However, we failed to show any statistically significant difference in the prevalence of malignancies or immune disorders between the indeterminate LAC and negative result groups. In spite of the multiple significant variables between the 2 groups, we expected most of these to lose significance in multivariate analysis due to the heterogeneity of our population, small cohort size, and confounding factors. Therefore, when we used a multivariate model (age, gender, malignancy, immune disease, DVT, and warfarin therapy), none of these reached statistical significance.

Although clinical follow-up of the indeterminate LAC group was documented for a mean of 18.6±12.8 months (median=22 months), laboratory follow-up was much less frequent. Of the 65 patients, only 19 (29%) had more than 1 test documented within 2 years before or after study enrollment. Two patients had incomplete repeated tests, and 1 test had a very high heparin level that could not be neutralized. Of the 16 patients with complete repeat testing, 6 (37.5%) had persistent indeterminate results, 6 had negative results (37.5%), and 4 (25%) had documented positive LAC profiles. Therefore, 10 of the 16 patients with repeated LAC testing had changed profile results during the 18-month follow-up period. However, we were not able to determine a trend of change in profile upon retesting, nor predictors for change due to the small number of patients with follow-up testing. We could not attribute the poor retesting rate to weak clinical suspicion, because these patients had similar clinical manifestations compared to those with positive tests. The Sapporo and revised ISTH criteria recommend retesting for patients with positive LAC on a second occasion greater than 12 weeks after the initial testing [6, 11]. In contrast, the clinical indication for repeat testing in patients who have indeterminate LAC results is not well established. Since 50% of our cohort that was retested had a change in their LAC profile status, repeating LAC testing in patients with clinical suspicion of thrombosis but indeterminate LAC results may be considered to establish or refute a diagnosis of LAC.

There is wide variability in the way LAC testing is performed between medical centers. Many centers perform LAC testing using an algorithmic approach with initial screening assays followed by mixing studies only if 1 or more screening test is abnormal; PL neutralization steps are only performed for samples with positive mixing studies. The testing methodology utilized in this study was different in that all screening, mixing, and PL tests were performed and the results were examined as a panel. It is clear from our results that abnormal PL-D tests can be seen in patients with normal screening tests and negative mixing studies.

This study has several weaknesses, including the retrospective design, very low retesting rate, heterogeneous referred patient population, and limited follow-up. Nevertheless, this study is the first to document a high prevalence of indeterminate results and to test its clinical significance. In conclusion, indeterminate results are common among patients referred for LAC testing. Compared to patients with negative results, patients with indeterminate results are more likely to have a history of DVT, superficial thrombosis, and MI; however, none of the clinical variables reached statistical significance in a multivariate model. On the other hand, patients in the indeterminate group shared demographic and clinical profiles with those in the positive results group. This highlights the need to study the clinical significance of indeterminate LAC results in a prospective study.

Go to :

Notes

Part of this work was presented at the annual American Hematology Society (ASH) meeting in New Orleans, LA, in 2009.

Go to :

References

1. Conley CL, Hartmann RC. A hemorrhagic disorder caused by circulating anticoagulant in patients with disseminated lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1952; 31:621–622.

2. Feinstein DI, Rappaport SI. Acquired inhibitors of blood coagulation. Prog Hemost Thromb. 1972; 1:75–95. PMID: 4569725.

3. Mueh JR, Herbst KD, Rapaport SI. Thrombosis in patients with the lupus anticoagulant. Ann Intern Med. 1980; 92:156–159. PMID: 7352719.

4. Galli M, Luciani D, Bertolini G, Barbui T. Lupus anticoagulants are stronger risk factors for thrombosis than anticardiolipin antibodies in the antiphospholipid syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. Blood. 2003; 101:1827–1832. PMID: 12393574.

5. Brandt JT, Triplett DA, Alving B, Scharrer I. Criteria for the diagnosis of lupus anticoagulants: an update On behalf of the Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Antibody of the Scientific and Standardisation Committee of the ISTH. Thromb Haemost. 1995; 74:1185–1190. PMID: 8560433.

6. Pengo V, Tripodi A, Reber G, et al. Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection. J Thromb Haemost. 2009; 7:1737–1740. PMID: 19624461.

7. Asherson RA. Antiphospholipid antibodies, malignancies and paraproteinemias. J Autoimmun. 2000; 15:117–122. PMID: 10968896.

8. Hughes GR, Khamashta MA. The antiphospholipid syndrome. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1994; 28:301–304. PMID: 7965966.

9. Greaves M, Cohen H, Machin SJ, Mackie I. Guidelines on the investigation and management of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2000; 109:704–715. PMID: 10929019.

10. Tripodi A, Chantarangkul V, Clerici M, Mannucci PM. Laboratory diagnosis of lupus anticoagulants for patients on oral anticoagulant treatment. Performance of dilute Russell viper venom test and silica clotting time in comparison with Staclot LA. Thromb Haemost. 2002; 88:583–586. PMID: 12362227.

11. Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006; 4:295–306. PMID: 16420554.

12. Olteanu H, Downes KA, Patel J, Praprotnik D, Sarode R. Warfarin does not interfere with lupus anticoagulant detection by dilute Russell's viper venom time. Clin Lab. 2009; 55:138–142. PMID: 19462936.

13. Petri M. Epidemiology of the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2000; 15:145–151. PMID: 10968901.

14. de Groot PG, Lutters B, Derksen RH, Lisman T, Meijers JC, Rosendaal FR. Lupus anticoagulants and the risk of a first episode of deep venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2005; 3:1993–1997. PMID: 16102105.

15. Sidelmann JJ, Sjøland JA, Gram J, et al. Lupus anticoagulant is significantly associated with inflammatory reactions inpatients with suspected deep vein thrombosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2007; 67:270–279. PMID: 17454841.

16. Leon L, Giannoukas AD, Dodd D, Chan P, Labropoulos N. Clinical significance of Superficial Vein Thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005; 29:10–17. PMID: 15570265.

17. Rees JD, Lanca S, Marques PV, et al. Prevalence of the antiphospholipid syndrome in primary systemic vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006; 65:109–111. PMID: 16344494.

18. Heneghan MA, Cleary B, Murray M, O'Gorman TA, McCarthy CF. Activated protein C resistance, thrombophilia, and inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1998; 43:1356–1361. PMID: 9635631.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download