Abstract

Background

Iron overload is a predictable and life-threatening complication in patients dependent on the regular transfusion of RBCs. The aims of this study were to investigate the efficacy and safety of deferiprone in a variety of pediatric hematologic and/or oncologic patients with a high iron overload.

Methods

Seventeen patients (age: 1.1-20.4 years; median: 10.6 years) from 7 hospitals who were treated with deferiprone from 2006 to 2009 were enrolled in this study. Medical records of enrolled patients were reviewed retrospectively.

Results

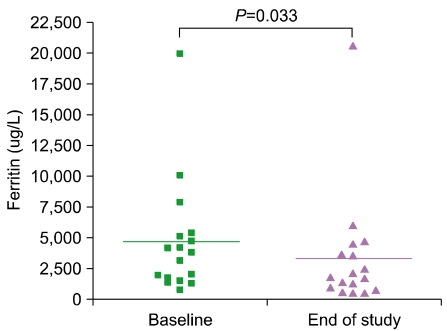

Serum ferritin levels were 4,677.8±1,130.9 µg/L at baseline compared to 3,363.9±1,149.7 µg/L at the end of deferiprone treatment (P=0.033). Only 1 patient developed neutropenia as a complication.

Conclusion

Deferiprone treatment is relatively safe for pediatric patients suffering from various hematologic and oncologic diseases that require RBC transfusions as part of treatment. However, the potential development of critical complications such as agranulocytosis and/or neutropenia remains a concern.

Go to :

Iron overload is a predictable and life-threatening complication in patients dependent on the regular transfusion of RBCs. In the absence of effective iron chelation therapy, chronic transfusions lead to iron accumulation in the liver, various endocrine organs, and the heart [1]. Numerous studies have reported that cardiac events due to iron overload in the heart are the primary cause of death in these patients [2-4]. Therefore, effective iron chelation to promote the excretion of the excess iron from target organs is essential to prevent the morbidity and mortality observed in patients with transfusion-dependent hematologic and/or oncologic disorders [5, 6].

Over the past decades, deferoxamine (Desferal) has been shown to prolong survival; improve growth and sexual maturation; and reduce hepatic, cardiac, and endocrine dysfunction in iron-overloaded patients [7]. Although deferoxamine can effectively stabilize or reduce body iron load, compliance with the demanding dose regimen can be an issue. Subcutaneous administration of this drug is frequently associated with local irritation at the site of the deferoxamine infusion. Moreover, deferoxamine has been associated with a variety of dose-related toxicities such as visual and auditory neurotoxicity, growth retardation, and bone morbidities. Due to these complications and the route of administration, many patients are noncompliant with deferoxamine therapy and therefore fail to achieve adequate iron chelation [1, 8-11].

Deferiprone (Ferriprox) is an iron-chelating agent in oral tablet form whose efficacy has been shown to be equivalent to that of deferoxamine [12-16]. In this study, we investigated the efficacy and safety of deferiprone in a variety of pediatric hematologic and/or oncologic patients with a high iron overload.

Go to :

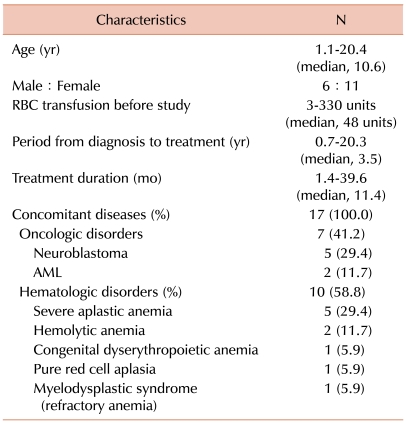

Seventeen patients (6 boys and 11 girls; age: 1.1-20.4 years; median: 10.6 years) from 7 hospitals who were treated with deferiprone from January 2006 to September 2009 were enrolled in this study. All patients received deferiprone as the first iron-chelating agent. The median dose of deferiprone was 25 mg/kg (range: 20-40 mg/kg). Seven patients were diagnosed with oncologic diseases and 10 with hematologic diseases. Among the oncologic patients, 5 were diagnosed with neuroblastoma and 2 were diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Hematologic disorders included severe aplastic anemia (SAA; 5 patients) hemolytic anemia (2 patients), congenital dyserythropoietic anemia (1 patient), pure red cell aplasia (1 patient), and myelodysplastic syndrome or refractory anemia (1 patient). The time period between diagnosis and the start of deferiprone treatment ranged from 0.7 to 20.3 years (median: 3.6 years). The median treatment duration of this study was 11.4 months (range: 1.4-39.6 months). All patients had received RBC transfusions (3-330 units; median: 48 units) for a median of 3 years (range: 1-13 years) (Table 1).

Patient data were collected from 7 hospitals in Korea in a retrospective manner, and the participating institutions were approved for inclusion in this study by the institutional review board of each hospital. Data collected for each patient consisted of the following: complete blood count (CBC); ferritin, serum creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels; concomitantly used drugs; and complications occurring between the start and end of deferiprone use. Toxicities were evaluated using common toxicity criteria (CTC; version 3.0). Cardiac evaluation was limited to patients with a history of the symptoms of heart failure and/or arrhythmia. In the present study, however, no cardiac symptoms were reported. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of deferiprone treatment, biochemical parameters such as serum ferritin and liver enzymes were analyzed using the Student t-test. All parameters are presented as mean±standard error (SE). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Go to :

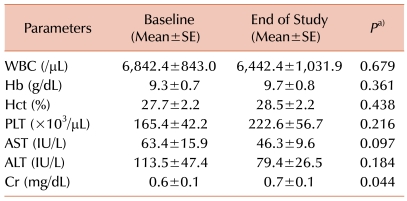

Serum ferritin levels were 4,677.8±1,130.9 µg/L at baseline compared to 3,363.9±1,149.7 µg/L at the end of deferiprone treatment (P=0.033; Fig. 1). Other hematologic parameters such as hemoglobin, white blood cell (WBC) count, and platelet count showed no significant changes (Table 2). Biochemical parameters for liver toxicity (AST and ALT) showed some diminution at the end of treatment but did not reach the level of statistical significance. Serum creatinine levels showed a slight increase at the end of deferiprone use, but levels were below normal both during and after the deferiprone treatment period (Table 2).

One patient experienced a mild degree of leucopenia (WBC count=1,870/µL; neutrophil count >1,000/µL), and medication was stopped immediately. The patient, a diabetic who had used insulin during the study period, received deferiprone 30 mg/kg for 9 months, followed by an increase in drug dose to 45 mg/kg. Seven months after the dose of deferiprone was increased, the patient's CBC indicated leucopenia. After cessation of the drug, the patient's WBC count gradually normalized.

Go to :

In this study, serum ferritin levels declined significantly from baseline to end of treatment course (4,677.8±1,130.9 µg/L vs. 3,363.9±1,149.7 µg/L; P=0.033; Fig. 1). Only 1 patient stopped taking medication owing to complications. This is similar to the results of previous studies in which deferiprone treatment prevented the progression of iron overload in transfusion-dependent patients, as demonstrated by the sequential assessments of serum ferritin concentrations [17-19]. In addition, the efficacy of deferiprone has been shown to be equivalent to that of deferoxamine in some studies [12-16].

While some adverse events were expected in the present study, complications occurred in only 1 patient (5.9%). No liver enzyme elevation or agranulocytosis (severe neutropenia, defined as an absolute neutrophil count [ANC] <500/µL) was reported; however, 1 case of neutropenia (defined as ANC >500/µL but <1,500/µL) was identified. Serum creatinine concentrations increased significantly; however, the levels of serum creatinine at the end of the study were in the clinically normal range (0.7±0.1 mg/dL). In a large, multicenter, long-term study of deferiprone treatment, the incidence of agranulocytosis was 1% [20]. This corresponds to a rate of 0.4 episodes per 100 patient-years of therapy. In the present study, agranulocytosis did not develop because of the small number of patients and the short study period (22.9 patient-years; data not shown). However, the overall incidence of neutropenia corresponds to a rate of 2.5 per 100 patient-years of exposure [20]. This incidence explains the results of the present study. Although the mechanism of neutropenia development may differ from the mechanism that results in agranulocytosis, thalassemia patients not treated with deferiprone are known to exhibit transient drops in the neutrophil count to a level defined as neutropenia [21]. In some studies, deferoxamine-treated patients experienced at least 1 episode of neutropenia, and these episodes are likely to be related to overactivity of the spleen, a condition that is often present in thalassemia patients [20, 22, 23].

The limitations of this study were the small number of patients, short period of follow-up time, and the heterogenous disease group. Seven patients had a malignant disease such as neuroblastoma and AML. Most studies on iron-chelating agents applied these agents to targeted hematologic disorders such as thalassemia. However, results of the present study show the effectiveness of deferiprone in pediatric patients with malignant or benign hematologic disease for which transfusion is needed during the course of treatment.

In conclusion, deferiprone treatment is relatively safe for pediatric patients suffering from various hematologic and oncologic diseases for which RBC transfusion is needed during treatment. However, critical complications such as neutropenia remain a concern.

Go to :

References

1. Gabutti V, Piga A. Results of long-term iron-chelating therapy. Acta Haematol. 1996; 95:26–36. PMID: 8604584.

2. Zurlo MG, De Stefano P, Borgna-Pignatti C, et al. Survival and causes of death in thalassaemia major. Lancet. 1989; 2:27–30. PMID: 2567801.

3. Olivieri NF, Nathan DG, MacMillan JH, et al. Survival in medically treated patients with homozygous beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:574–578. PMID: 8047081.

4. Sonakul D, Thakerngpol K, Pacharee P. Cardiac pathology in 76 thalassemic patients. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1988; 23:177–191. PMID: 3390539.

5. Barman Balfour JA, Foster RH. Deferiprone: a review of its clinical potential in iron overload in beta-thalassaemia major and other transfusion-dependent diseases. Drugs. 1999; 58:553–578. PMID: 10493280.

6. Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM. Iron-chelating therapy and the treatment of thalassemia. Blood. 1997; 89:739–761. PMID: 9028304.

7. Brittenham GM, Griffith PM, Nienhuis AW, et al. Efficacy of deferoxamine in preventing complications of iron overload in patients with thalassemia major. N Engl J Med. 1994; 331:567–573. PMID: 8047080.

9. al-Refaie FN, Wonke B, Hoffbrand AV, Wickens DG, Nortey P, Kontoghiorghes GJ. Efficacy and possible adverse effects of the oral iron chelator 1,2-dimethyl-3-hydroxypyrid-4-one (L1) in thalassemia major. Blood. 1992; 80:593–599. PMID: 1638018.

10. Porter J. Oral iron chelators: prospects for future development. Eur J Haematol. 1989; 43:271–285. PMID: 2684681.

11. Olivieri NF, Buncic JR, Chew E, et al. Visual and auditory neurotoxicity in patients receiving subcutaneous deferoxamine infusions. N Engl J Med. 1986; 314:869–873. PMID: 3485251.

12. Taher A, Abou-Mourad Y, Abchee A, Zalouaa P, Shamseddine A. Pulmonary thromboembolism in beta-thalassemia intermedia: are we aware of this complication? Hemoglobin. 2002; 26:107–112. PMID: 12144052.

13. Maggio A, D'Amico G, Morabito A, et al. Deferiprone versus deferoxamine in patients with thalassemia major: a randomized clinical trial. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002; 28:196–208. PMID: 12064916.

14. Piga A, Gaglioti C, Fogliacco E, Tricta F. Comparative effects of deferiprone and deferoxamine on survival and cardiac disease in patients with thalassemia major: a retrospective analysis. Haematologica. 2003; 88:489–496. PMID: 12745268.

15. Fischer R, Longo F, Nielsen P, Engelhardt R, Hider RC, Piga A. Monitoring long-term efficacy of iron chelation therapy by deferiprone and desferrioxamine in patients with beta-thalassaemia major: application of SQUID biomagnetic liver susceptometry. Br J Haematol. 2003; 121:938–948. PMID: 12786807.

16. Peng CT, Chow KC, Chen JH, Chiang YP, Lin TY, Tsai CH. Safety monitoring of cardiac and hepatic systems in beta-thalassemia patients with chelating treatment in Taiwan. Eur J Haematol. 2003; 70:392–397. PMID: 12756022.

17. Mazza P, Amurri B, Lazzari G, et al. Oral iron chelating therapy. A single center interim report on deferiprone (L1) in thalassemia. Haematologica. 1998; 83:496–501. PMID: 9676021.

18. Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM, Matsui D, et al. Iron-chelation therapy with oral deferipronein patients with thalassemia major. N Engl J Med. 1995; 332:918–922. PMID: 7877649.

19. Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM, McLaren CE, et al. Long-term safety and effectiveness of iron-chelation therapy with deferiprone for thalassemia major. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:417–423. PMID: 9700174.

20. Ceci A, Baiardi P, Felisi M, et al. The safety and effectiveness of deferiprone in a large-scale, 3-year study in Italian patients. Br J Haematol. 2002; 118:330–336. PMID: 12100170.

21. Modell B, Berdoukas V, editors. Clinical Approach to Thalassaemia. 1984. London: Grune & Stratton.

22. Cohen AR, Galanello R, Piga A, Dipalma A, Vullo C, Tricta F. Safety profile of the oral iron chelator deferiprone: a multicentre study. Br J Haematol. 2000; 108:305–312. PMID: 10691860.

23. Orkin SH, Nathan DG, editors. The Thalassemias. 1998. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download