Abstract

Background

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an acquired clonal disorder characterized by chronic complement-mediated hemolysis. Eculizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the terminal complement protein C5, potently reduces chronic intravascular hemolysis. We tested the clinical efficacy and safety of a 24-week treatment with eculizumab in 6 Korean patients with PNH.

Methods

We enrolled 6 patients with PNH who had clinically significant hemolysis. Eculizumab was administered intravenously at 600 mg/week for the first 4 weeks followed by 900 mg at week 5 and 2nd weekly thereafter.

Results

Three men and 3 women with a median age of 39.5 years (24-61 years) were enrolled. The median duration of PNH was 11 years (6-25 years). Hemolysis occurred in all patients [median lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, 7.95 times the upper limit of the reference range of LDH]. All patients treated with eculizumab had a rapid and sustained reduction in the degree of hemolysis. RBC transfusion requirements for 3 months were decreased from 0-12 units (median requirement, 1.5 units) to 0-6 units (median requirement, 0 units). Improvement in fatigue was noted in 4 patients. Further, 5 patients who had been receiving corticosteroids either reduced the dose or discontinued therapy. No significant adverse events related to eculizumab therapy were observed.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an acquired clonal disorder caused by a somatic mutation in the phosphatidylinositol glycan-complementation class A (PIGA) gene in hematopoietic stem cells [1-3]. Patients with PNH present with intravascular hemolytic anemia, bone marrow failure, and thrombosis. Many of the clinical manifestations of PNH result from complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis. The life-threatening condition of thromboembolism (TE) is the most common cause of death in patients with PNH, at least in Western populations (TE accounts for 40-67% of patient deaths in these populations) [1-3]. On the other hand, the incidence of TE is much lower in Asian countries [2, 3]. Previously, the management of PNH had been palliative and non-targeted, and it focused on treating the symptoms of anemia and episodic hemolysis rather than the underlying chronic hemolysis associated with disease progression. Presently, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is the only curative therapy for PNH. Available supportive care options include blood transfusions and nonspecific drug treatments including, but not limited to, steroids and anticoagulants [4, 5]. The results of a retrospective analysis of 286 PNH patients from a national registry in South Korea indicated that the cumulative incidence of TE was 15%; TE was a strong predictor of mortality [6]. Despite medical intervention with supportive care (78% of the patients used corticosteroids), patients continued to show disabling symptoms, progressive complications, and early mortality [7].

Eculizumab (Soliris®; Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Cheshire, CT, USA), a humanized monoclonal antibody against the terminal complement protein C5, has a direct and potent effect on chronic intravascular hemolysis [4, 5, 8]. In 2007, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of eculizumab against PNH on the basis of its efficacy in 2 phase 3 clinical trials [9-11]. Eculizumab is highly effective in reducing intravascular hemolysis in PNH patients, and treatment with eculizumab decreases or eliminates the need for blood transfusions; improves the quality of life; and reduces pulmonary hypertension, chronic kidney disorders, and the risk of thrombosis [9-11]. In this study, we tested the clinical efficacy and safety of eculizumab for treating Korean patients with PNH. We report the results of a 24-week treatment with eculizumab.

A total of 6 Korean patients with PNH, who were selected from 5 institutions and had clinically significant hemolysis, received eculizumab therapy. This study was initiated in December 2009 and is currently ongoing. Patients who were ≥18 years of age, had a PNH granulocyte proportion of ≥10%, and had lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels of at least 1.5 times the upper limit of the reference range (ULN) of LDH were eligible. Further, patients with a history of thrombosis or associated symptoms were included in this study. Patients receiving stable doses of anticoagulants, iron supplements, and immunosuppressive drugs, including corticosteroids, were also included. Patients were excluded, if the platelet count was <20×109/L; absolute neutrophil count (ANC), <0.5×109/L; and corrected reticulocyte count, <1%. Patients with complement deficiency, active bacterial infection, prior meningococcal disease, or prior hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were also excluded.

Eculizumab was administered intravenously at a dose of 600 mg/week (±2 days) for the first 4 weeks 900 mg at week 5 and 2nd weekly thereafter. Two weeks before the therapy was initiated, all patients were vaccinated against Neisseria meningitidis, because the inhibition of complement C5 increases the risk of developing neisserial infections. Throughout the study, the patients received RBC transfusions, if the transfusions were medically indicated. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their enrolment in this study.

We obtained the following information of the patients: baseline clinical characteristics; demographics, laboratory values; LDH, RBC, Hb, reticulocyte, WBC, ANC, platelet, creatinine level, PNH clone size, medical history, symptoms, history of TE, and treatment history. We regularly checked the Hb levels and degree of hemolysis by measuring the LDH levels, and collected information regarding any adverse events at each dosing visit. We evaluated the degree of fatigue by using the validated Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) instrument [12] from baseline. Total scores on the FACIT-Fatigue instrument range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating an improvement in fatigue. An increase of ≥3 points is considered clinically significant for this instrument [12].

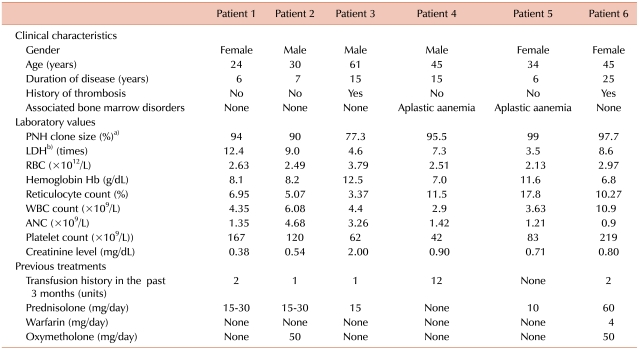

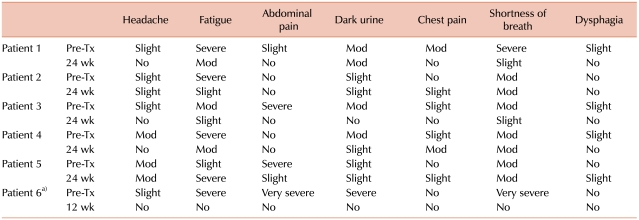

Three men and 3 women with a median age of 39.5 years (24-61 years) were enrolled in this study. The median duration of PNH was 11 years (6-25 years). All patients were diagnosed with PNH on the basis of flow cytometric analysis of WBCs (CD59). The PNH clones in all patients were large (median granulocyte clone size, 94.75%; range, 77.3-99%). Of the 6 patients, 2 were previously diagnosed with aplastic anemia (PNH/aplastic anemia); the other 4 had classic PNH. All the patients had anemia (median Hb, 8.15 g/dL; range, 6.8-12.5 g/dL). Median neutrophil and platelet counts were 1.38×109/L [range, (0.9 to 4.68)×109/L] and 1.01×1011/L [range, (0.42 to 2.19)×1011/L], respectively. Further, 4 patients had thrombocytopenia [platelet count, (0.42 to 1.2)×1011/L] and 2 had neutropenia (WBC count, <4.0×109/L). Before treatment with eculizumab, 5 patients had received RBC transfusions and 5 had been treated with corticosteroids; none were treated with immunosuppressive agents. Moreover, 2 patients had a history of thrombosis, and 1 patient had been receiving warfarin. Hemolysis was noted in all patients, and it was evaluated by the levels of LDH (median LDH level, 7.95 times the ULN of LDH; range, 3.5-12.4 times) (Table 1). Furthermore, all the patients had fatigue and hemoglobinuria, before eculizumab therapy was initiated. Severe fatigue was noted in 4 patients, and severe abdominal pain in 3 patients (Table 2).

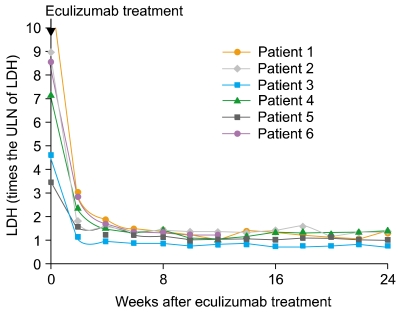

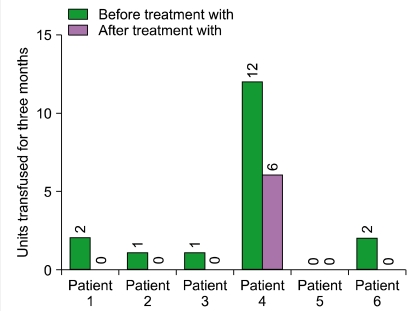

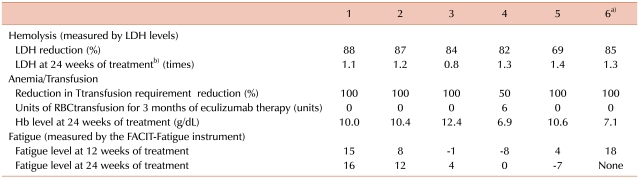

Of the 6 patients, 5 completed the 24-week therapy with eculizumab. The sixth patient completed only 12 weeks of treatment, because he was enrolled later than the other patients. All patients treated with eculizumab had a rapid and sustained reduction in the degree of hemolysis. The reduction was evaluated by the change in LDH levels, and this reduction was observed in all patients (median reduction at 24 weeks, 84.5%; range, 69-88%) (Table 3). In all the patients, the decrease in the LDH levels began after they received a single dose of eculizumab, and LDH levels remained within or just above the reference range during eculizumab therapy (Fig. 1). The median LDH level at 24 weeks was 1.25 times the ULN of LDH. The reduction in the degree of hemolysis resulted in an improvement in anemia, and the median Hb level at 24 weeks was 10.2 g/dL (range, 6.9-12.4 g/dL). During the 3 months preceding enrollment, the RBC transfusion requirement of the patients was 0-12 units (median requirement, 1.5 units), whereas during the first 3 months of this study, the range was reduced to 0-6 units (median requirement, 0 units). Only 1 patient who had PNH/aplastic anemia remained transfusion-dependent (Fig. 2). However, the units transfused were reduced from 12 units/3 months before treatment to 6 units during the initial 3 months of treatment (50% reduction).

Fatigue was assessed by using the FACIT-Fatigue instrument. Improvement in fatigue was noted in 4 patients (67%). The FACIT-Fatigue scores improved by a median of 8 points during the first 24 weeks of eculizumab therapy, and only 1 patient had decreased scores after therapy (Table 2). Further, after the therapy, significant improvement in abdominal pain was noted in the 3 patients who had severe abdominal pain before treatment (Table 2).

One patient who had been receiving warfarin for preventing further thrombotic events discontinued the anticoagulation therapy after the initiation of eculizumab therapy. Moreover, after starting eculizumab therapy, 5 patients who were being treated with corticosteroids reduced the dose of the corticosteroid (N=1, prednisolone dose was reduced from 60 mg/day to 3-12 mg/day) or discontinued the corticosteroid therapy (N=4).

There were no significant adverse events related to eculizumab therapy. Mild to moderate headache was noted in 2 patients, and mild abdominal pain in only 1 patient (Table 2). Only 1 patient had a moderate degree of nausea and vomiting. There were no cases of severe systemic infections. None of the patients developed new thrombotic events during the course of the treatment.

PNH is a chronic, often fatal disease characterized by symptoms of fatigue and intermittent episodes of dysphagia, abdominal pain, and hemoglobinuria [1]. The median survival time after diagnosis is about 10 years. The life-threatening condition of TE is the most fatal complication of PNH [1-3]. Presently, allogeneic BMT is the only curative therapy for PNH, but this therapy is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry reported that the 2-year survival probability was 56% in 48 recipients of HLA-identical sibling BMT between 1978 and 1995 [13]. Therefore, supportive treatments, including RBC transfusion and corticosteroid therapy, have been generally used for reducing the symptoms in PNH patients. However, these medical interventions cannot prevent the progressive complications and early mortality associated with this disease [1-3].

Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that prevents the activation of complement C5 and the subsequent formation of the cytolytic membrane attack complex of complement. Since the introduction of eculizumab for the treatment of PNH, few cases from Asian countries have been reported. In this study, we evaluated the safety and efficacy of eculizumab for treating Korean patients with PNH. No serious infusion-related problems were noted during the treatment period. We confirm that both the previously recommended dose and administration interval of eculizumab are safe and well tolerated in Korean patients with PNH.

We observed rapid and sustained reduction of LDH levels to, or just above, the ULN of LDH during eculizumab therapy in Korean patients with relatively large PNH clones (median granulocyte clone size, 94.75%). The median LDH level decreased from 7.95 times the ULN of LDH at baseline to 1.25 times the ULN at 24 weeks. The reduction in the degree of hemolysis after eculizumab therapy was associated with a significant improvement in anemia, which was indicated by a rise in the Hb level from a median level of 8.15 g/dL at baseline to 10.2 g/dL at 24 weeks. We also observed stabilization of the number of RBC units transfused. Among the 2 patients who were previously diagnosed with PNH/aplastic anemia, 1 patient remained transfusion-dependent during eculizumab therapy (1/6). However, the RBC units transfused were reduced from 12 units/3 months before treatment to 6 units during the initial 3 months of treatment (50% reduction). In the open-label, 52-week, Phase 3 study (SHEPHERD) [11], the reductions in transfusion were observed even in patients with baseline platelet counts of <65×109/L. These data suggest that patients with both classic PNH and PNH associated with other bone marrow failure syndromes will benefit from eculizumab therapy. However, when appropriate, young PNH patients with life-threatening cytopenias (e.g., severe aplastic anemia) should be recommended allogeneic BMT.

Fatigue is a common symptom in patients with PNH, and it occurs not only because of anemia but is also closely linked to hemolysis and nitric oxide depletion due to chronic hemolysis [1, 2]. In previous trials, the FACIT-Fatigue scores significantly improved within 1 week of treatment (median increase, 3 points), and this effect sustained throughout a period of 52 weeks (overall median increase, 10 points) [11]. A change of ≥3 points on the FACIT-Fatigue instrument is considered clinically significant [12]. We observed a significant improvement in the FACIT-Fatigue scores of 4 patients after eculizumab therapy (median increase at 24 weeks, 8 points), but the scores of 1 patient decreased, and this change should be further evaluated with longer follow-up. According to previous clinical trials, headache occurs in approximately 50% of the patients during eculizumab therapy [11]. We noted 2 cases (33%) of mild to moderate headache in this study. Although neisserial sepsis was the most serious complication and other infections were a common side effect of eculizumab therapy, previous clinical trial data suggest that the infections were mild to moderate in nature and not related to eculizumab therapy [9-11]. In this trial, we could not find clinically significant infections during eculizumab therapy. As there were no significant adverse events and no newly developed TE events during the eculizumab therapy, eculizumab treatment appeared to be safe in Korean patients with PNH.

After eculizumab therapy, 5 patients who were being treated with corticosteroids reduced the dose of the corticosteroid (N=1) or discontinued corticosteroid therapy (N=4); hence, eculizumab therapy may reduce or eliminate the serious side effects of corticosteroids in patients with PNH. Previous clinical trials have shown that the TE event rate showed a significant reduction in 24 weeks during eculizumab treatment (92%) than in the same time period before treatment [10, 11]. The discontinuation of the anticoagulation therapy after the initiation of eculizumab therapy in patients with a history of TEs is still controversial. Only 1 patient who had been receiving warfarin before eculizumab therapy discontinued the medication during the therapy. Thus, eculizumab may reduce or eliminate the several serious toxicities associated with anticoagulation therapy in patients in whom the therapy was discontinued.

In conclusion, this study is the first report on the efficacy and safety of eculizumab for treating Korean patients with PNH. This study showed that eculizumab reduced both the degree of intravascular hemolysis and the need for RBC transfusion. Further, improvements in anemia, fatigue, and quality of life were noted after eculizumab treatment. However, the long-term efficacy and safety of eculizumab should be further evaluated in a larger study population.

References

1. Hillmen P, Lewis SM, Bessler M, Luzzatto L, Dacie JV. Natural history of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 1995; 333:1253–1258. PMID: 7566002.

2. Nishimura J, Kanakura Y, Ware RE, et al. Clinical course and flow cytometric analysis of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in the United States and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004; 83:193–207. PMID: 15118546.

3. de Latour RP, Mary JY, Salanoubat C, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: natural history of disease subcategories. Blood. 2008; 112:3099–3106. PMID: 18535202.

4. Parker C, Omine M, Richards S, et al. Diagnosis and management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2005; 106:3699–3709. PMID: 16051736.

5. Brodsky RA. How I treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2009; 113:6522–6527. PMID: 19372253.

6. Lee JW, Jang JH, Lee JH, et al. High prevalence and mortality associated with thromboembolism in Asian patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). Haematologica. 2010; 95(suppl 2):205. (abst 505).

7. Lee JW, Jang JH, Lee JH, et al. Clinical symptoms of hemolysis are predictive of disease burden and mortality in Asian patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). Haematologica. 2010; 95(suppl 2):206. (abst 506). PMID: 19773262.

8. Parker C. Eculizumab for paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Lancet. 2009; 373:759–767. PMID: 19144399.

9. Hillmen P, Hall C, Marsh JC, et al. Effect of eculizumab on hemolysis and transfusion requirements in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2004; 350:552–559. PMID: 14762182.

10. Hillmen P, Young NS, Schubert J, et al. The complement inhibitor eculizumab in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:1233–1243. PMID: 16990386.

11. Brodsky RA, Young NS, Antonioli E, et al. Multicenter phase 3 study of the complement inhibitor eculizumab for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2008; 111:1840–1847. PMID: 18055865.

12. Cella D. Manual of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System. 1997. 4th ed. Evanston, IL: Center on Outcomes Research and Education (CORE), Evanston Northwestern Healthcare and Northwestern University;p. 13–19.

13. Saso R, Marsh J, Cevreska L, et al. Bone marrow transplants for paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Br J Haematol. 1999; 104:392–396. PMID: 10050724.

Fig. 1

Changes in the levels of lactate dehydrogenase during treatment with eculizumab. Abbreviations: LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of the normal reference range.

Fig. 2

Reduction in the number of units of red blood cell transfused during treatment with eculizumab.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download