Abstract

Background

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is characterized by platelet and neutrophil activation. Platelets are the major source of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Endostatin, an anti-angiogenic factor, is a fragment of collagen that is released from the extracellular matrix via the active cleavage of neutrophil elastase, thereby increasing the circulating level of endostatin. Hypercoagulable conditions such as DIC may induce the release of VEGF and neutrophil elastase from the platelets and neutrophils.

Methods

We enrolled 240 patients who were clinically suspected of having DIC. Plasma levels of VEGF, endostatin, and neutrophil elastase were determined using commercial ELISA kits. Patients were diagnosed as having overt DIC if the cumulative International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Subcommittee score was >5.

Results

Overt DIC was diagnosed in 80 of the 240 patients. The circulating VEGF and neutrophil elastase levels gradually increased according to the severity of coagulopathy, as reflected by the DIC score. However, the circulating endostatin level did not change significantly according to the DIC score. We divided the patients into 2 groups: the non-cancer and cancer patient groups, to exclude the VEGF release from tumor tissues. Interestingly, in non-cancer patients, higher VEGF and neutrophil elastase levels were found to be significant diagnostic markers for overt DIC.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is characterized by the widespread activation of the coagulation process, which results in the formation of intravascular fibrin [1]. There is no laboratory test that can be reliably used for the definite diagnosis of DIC. The International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) subcommittee on DIC has proposed laboratory criteria for overt DIC [2]. These laboratory criteria for calculating the overt DIC score included platelet count, a fibrin-related marker level, prothrombin time (PT), and fibrinogen activity.

In DIC, high levels of thrombin and many inflammatory cytokines are generated; this leads to the activation of platelets. Platelet activation has been shown to result in the release of numerous angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, angiopoietin-1, insulin-like growth factor-1, epidermal growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor [3]. Among these angiogenic factors, VEGF is a well-known angiogenic marker, and the levels of circulating VEGF have been shown to be a surrogate marker of angiogenic activity in various cancers and inflammatory diseases [4, 5].

Neutrophil activation also occurs due to microcirculatory disturbance during DIC [6]. Upon the activation of neutrophils, neutrophil elastase is released from their cytoplasmic granules. Neutrophil elastase is a serine protease that can cleave many extracellular matrix proteins. Endostatin, an anti-angiogenic factor, is a C-terminal fragment of collagen type XVIII, which can be released from the extracellular matrix via protease enzymes such as neutrophil elastase and cathepsin L [7, 8]. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that hypercoagulable conditions such as DIC may induce the release of VEGF and neutrophil elastase from platelets and neutrophils. The level of circulating endostatin can also be increased via the active cleavage by serine proteases such as neutrophil elastase. In this study, the levels of circulating VEGF, endostatin, and neutrophil elastase were investigated as possible diagnostic markers for overt DIC.

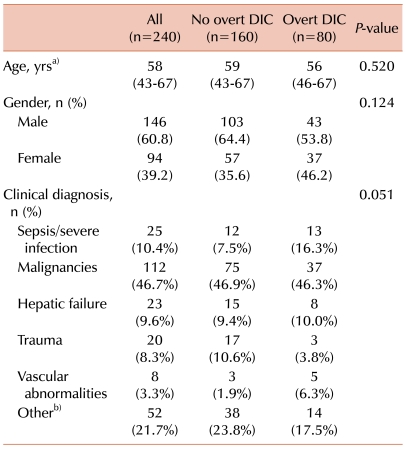

In all, 240 patients who were clinically suspected of having DIC were requested to undergo DIC screening battery tests and recruited for this study. Exclusion criteria were thrombotic or bleeding disorders and warfarin or heparin medications within 3 days of blood collection. The characteristics of the patients, including their underlying disorders, are described in Table 1. Patients were diagnosed as having overt DIC if the cumulative score of the ISTH Sub committee scoring system was >5 [2]. We arbitrarily classified the patients who did not meet the criteria for overt-DIC (a cumulative score of <5) as "no overt-DIC."

Peripheral blood was collected in commercially available sodium citrate tubes (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). The whole blood samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 1550 × g within 2 h after blood sampling. The prothrombin time and fibrinogen activity were determined by performing the standard clotting assay on a STA-R analyzer (Diagnostica Stago, Asnières, France). Plasma levels of VEGF, endostatin, and neutrophil elastase were determined using the following commercial ELISA kits: Quantikine human VEGF (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), endostatin protein Accucyte (Oncogene Research Products, San Diego, CA, USA), and polymorphonuclear (PMN) elastase/α1-proteinase inhibitor complex (Oncogene Research Products), respectively.

All statistical analyses were carried out using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) 12.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous data comparisons were performed using Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests, and the relationships between categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. The plasma levels of VEGF, endostatin, and neutrophil elastase were categorized into 2 groups according to the best cutoff values of diagnostic efficacy using MedCalc (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Odds ratios (OR), as measures of the relative risk of distant metastasis, were estimated using multivariate logistic regression analysis, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed. Two-sided P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Overt DIC was diagnosed in 80 of the 240 patients according to the ISTH diagnostic criteria. The characteristics of the patients were compared between the no overt DIC and overt DIC groups (Table 1). There were no differences with respect to age, gender, and clinical diagnosis between the no overt DIC and overt DIC patients.

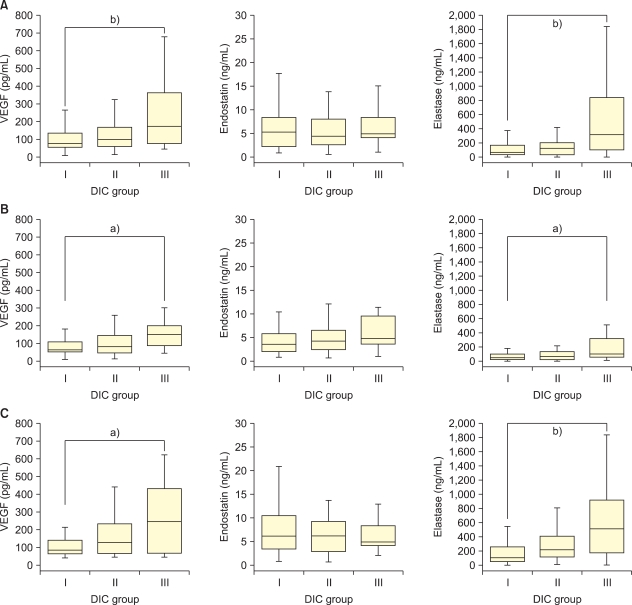

To determine whether the levels of VEGF, endostatin, and neutrophil elastase correlated with coagulopathy, we divided the patients into 3 groups according to the DIC score. In all the patients, the serum level of VEGF increased as the DIC score increased (Fig. 1A). Because cancer tissues might show increased VEGF secretion, we separated non-cancer patients from cancer patients. Both in cancer and non-cancer patients, the level of VEGF correlated with the degree of coagulopathy (Fig. 1B, C). Similarly, the level of neutrophil elastase increased according to the DIC scores in all, cancer, and non-cancer patients. On the other hand, the level of endostatin showed no significant difference according to the DIC scores.

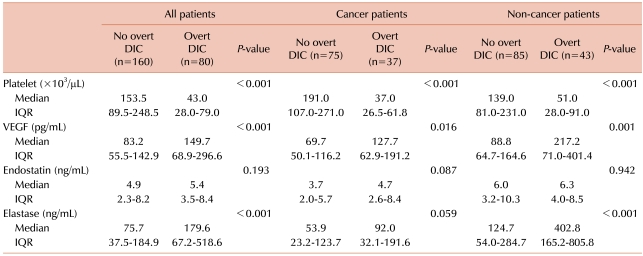

Platelet count, a critical marker for the diagnosis of DIC, differed significantly between the no overt DIC and overt DIC groups (Table 2). The level of VEGF was higher in the overt DIC group than in the no overt DIC group in all (P<0.001), cancer (P=0.016), and non-cancer patients (P=0.001). Similarly, the level of neutrophil elastase was higher in the overt DIC group than in the no overt DIC group, while that of endostatin showed no significant difference between the no overt DIC and overt DIC groups.

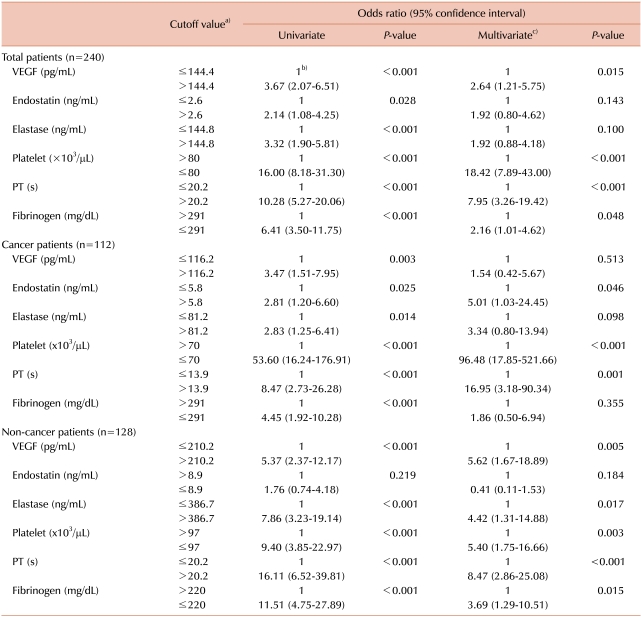

To assess the previously known and new potential markers for predicting overt DIC, we analyzed the OR of each parameter for the diagnosis of overt DIC using logistic regression test (Table 3). The cutoff value for each parameter was defined by the points yielding the best diagnostic accuracy for overt DIC in the relative operating characteristic (ROC) curves. In univariate logistic regression analysis, decreased platelet count, prolonged PT, and lower fibrinogen level were found to be related with the increased risk of overt DIC (OR for platelet, PT, and fibrinogen: in all patients: 16.00, 10.28, and 6.41, respectively; in cancer patients: 53.60, 8.47, 4.45, respectively; and in non-cancer patients: 9.40, 16.11, 11.51, respectively; P<0.001 in each analysis). Among the new potential markers, higher levels of VEGF and neutrophil elastase were found to be good predictors of overt DIC in univariate analysis (OR of VEGF and neutrophil elastase: in all patients: 3.67 and 3.32, respectively; in cancer patients: 3.47 and 2.83, respectively; and in non-cancer patients: 5.37 and 7.86, respectively; P<0.003 in each analysis).

In multivariate analysis adjusted for patient's age, sex, platelet count, PT, and fibrinogen level (Table 3), decreased platelet count and prolonged PT were found to be significant predictors of overt DIC (OR of platelet and PT: in all patients: 18.42 and 7.95, respectively; in cancer patients: 96.48 and 16.95, respectively; and in non-cancer patients: 5.40 and 8.47, respectively; P<0.003 in each analysis). A lower level of fibrinogen was a significant predictor in all cancer and non-cancer patients (OR, 2.16; P=0.048 in all patients; OR, 3.69; P=0.015 in non-cancer patients), but not in cancer patients. Among the new potential markers, a higher level of VEGF was a significant predictor in non-cancer patients. In non-cancer patients, the OR of VEGF (OR, 5.62) was comparable with that of platelet count (OR, 5.40). However, in cancer patients, the VEGF level did not show significant OR. Significant increase in neutrophil elastase level was observed only in non-cancer patients (OR, 4.42; P=0.017).

This study showed that the levels of circulating VEGF and neutrophil elastase gradually increased according to the severity of coagulopathy as reflected by the DIC score. However, there was no difference in the circulating endostatin level according to the DIC scores. We also demonstrated that the elevated circulating level of VEGF and neutrophil elastase were significant diagnostic markers of overt DIC, especially, in non-cancer patients.

VEGF, which is also known as vascular permeability factor, is one of the most pivotal angiogenic factors [9]. Circulating VEGF levels have been shown to be associated with poor prognosis of cancer and to be a surrogate marker of angiogenic activity in various cancers [4]. VEGF can also be elevated in various benign disorders because platelets, monocytes, and endothelial cells can release VEGF into the blood circulation. Platelets are a major source of soluble VEGF in the peripheral blood [10]. In our study, the level of circulating VEGF was elevated probably because of the activation of platelets during ongoing coagulopathy. We divided the total patient population into the following 2 groups: the non-cancer and cancer patient groups, to exclude the VEGF release from tumor tissues. Interestingly, in non-cancer patients, higher VEGF levels were found to be a significant diagnostic marker for overt DIC. However, this was not observed in cancer patients, suggesting that VEGF secreted from cancer tissues may obscure the VEGF measurement produced by the activation of coagulation.

Neutrophils are activated during DIC due to intravascular disturbance and formation of cytokines, endotoxins, or microclots. Upon stimulation, a neutrophil granule may release neutrophil elastase. Therefore, neutrophil elastase is considered as a marker of neutrophil activation. Neutrophil elastase is known to be elevated in severe DIC [6]. Consistent with a previous report [6], our data showed that neutrophil elastase levels increased depending on the severity of coagulopathy.

Endostatin is an anti-angiogenic factor. Originally, endostatin was best known for its antitumor activity in animal models [7]. Several studies also showed that the level of serum endostatin decreased in some forms of cancers [11, 12]. However, there have been only a few reports that focused on the circulating level of endostatin in benign conditions [13]. Because endostatin is a C-terminal fragment of collagen type XVIII, endostatin generation is at least partly mediated via the activity of protease enzymes such as neutrophil elastase and cathepsin L [7, 8]. In DIC, many serine proteases, including factor Xa, thrombin, as well as neutrophil elastase, are increased. The circulating endostatin level can be elevated due to the active cleavage of serine proteases. However, the circulating endostatin level did not increase in severe coagulopathy in our study. To verify this assumption, more sensitive measurement techniques to detect subtle changes in circulating endostatin levels may be required.

In conclusion, we showed that the levels of VEGF and neutrophil elastase showed a good correlation with the severity of coagulopathy. Furthermore, elevated levels of circulating VEGF and neutrophil elastase were found to be significant predictors of overt DIC in non-cancer patients. These findings suggest that the levels of circulating VEGF and neutrophil elastase are potential diagnostic markers of overt DIC, especially in non-cancer patients.

References

1. Bick RL. Disseminated intravascular coagulation: objective clinical and laboratory diagnosis, treatment, and assessment of therapeutic response. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1996; 22:69–88. PMID: 8711492.

2. Taylor FB Jr., Toh CH, Hoots WK, Wada H, Levi M. Scientific Subcommittee on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2001; 86:1327–1330. PMID: 11816725.

3. Folkman J, Broeder T, Palmblad J. Angiogenesis research: guidelines for translation to clinical application. Thromb Haemost. 2001; 86:23–33. PMID: 11487011.

4. Poon RT, Fan ST, Wong J. Clinical implications of circulating angiogenic factors in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19:1207–1225. PMID: 11181687.

5. Nagashima M, Asano G, Yoshino S. Imbalance in production between vascular endothelial growth factor and endostatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000; 27:2339–2342. PMID: 11036826.

6. Song SH, Kim HK, Park MH, Cho HI. Neutrophil CD64 expression is associated with severity and prognosis of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb Res. 2008; 121:499–507. PMID: 17597188.

7. O'Reilly MS, Boehm T, Shing Y, et al. Endostatin: an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997; 88:277–285. PMID: 9008168.

8. Wen W, Moses MA, Wiederschain D, Arbiser JL, Folkman J. The generation of endostatin is mediated by elastase. Cancer Res. 1999; 59:6052–6056. PMID: 10626789.

9. Miller JW, Adamis AP, Shima DT, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor is temporally and spatially correlated with ocular angiogenesis in a primate model. Am J Pathol. 1994; 145:574–584. PMID: 7521577.

10. Gunsilius E, Petzer A, Stockhammer G, et al. Thrombocytes are the major source for soluble vascular endothelial growth factor in peripheral blood. Oncology. 2000; 58:169–174. PMID: 10705245.

11. Feldman AL, Alexander HR Jr., Yang JC, et al. Prospective analysis of circulating endostatin levels in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2002; 95:1637–1643. PMID: 12365010.

12. Zhao J, Yan F, Ju H, Tang J, Qin J. Correlation between serum vascular endothelial growth factor and endostatin levels in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2004; 204:87–95. PMID: 14744538.

13. Takeshita S, Kawamura Y, Takabayashi H, Yoshida N, Nonoyama S. Imbalance in the production between vascular endothelial growth factor and endostatin in Kawasaki disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005; 139:575–579. PMID: 15730405.

Fig. 1

Plasma VEGF, endostatin, and elastase levels based on the DIC score in total (A), cancer (B), and non-cancer (C) patients. The upper and lower limits of each box represent the value of 25 and 75 percentile, respectively, and the bar represents the range of the levels of analyte. DIC groups I, II, and III included the patients with DIC score of 0-3, 4-5, and 6 or more, respectively. a)P<0.05, b)P<0.001. VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Table 1

Characteristics of the study population.

a)The values are presented as the median with interquartile range in parentheses, b)Other clinical diagnosis included neurological diseases (spinal stenosis, meningeal disease, and cranial infarct), respiratory diseases (asthma, asphyxia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder), coronary artery diseases, deep vein thrombosis, renal failure, diabetes, and benign prostate hyperplasia. Abbreviation: DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download