Abstract

Purpose

To examine changes in clinical practice patterns following the introduction of diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) under the fee-for-service payment system in July 2013 among Korean tertiary hospitals and to evaluate its effect on the quality of hospital care.

Materials and Methods

Using the 2012–2014 administrative database from National Health Insurance Service claim data, we reviewed medical information for 160400 patients who underwent cesarean sections (C-secs), hysterectomies, or adnexectomies at 43 tertiary hospitals. We compared changes in several variables, including length of stay, spillover, readmission rate, and the number of simultaneous and emergency operations, from before to after introduction of the DRGs.

Results

DRGs significantly reduced the length of stay of patients undergoing C-secs, hysterectomies, and adnexectomies (8.0±6.9 vs. 6.0±2.3 days, 7.4±3.5 vs. 6.4±2.7 days, 6.3±3.6 vs. 6.2±4.0 days, respectively, all p<0.001). Readmission rates decreased after introduction of DRGs (2.13% vs. 1.19% for C-secs, 4.51% vs. 3.05% for hysterectomies, 4.77% vs. 2.65% for adnexectomies, all p<0.001). Spillover rates did not change. Simultaneous surgeries, such as colpopexy and transobturator-tape procedures, during hysterectomies decreased, while colporrhaphy during hysterectomies and adnexectomies or myomectomies during C-secs did not change. The number of emergency operations for hysterectomies and adnexectomies decreased.

Conclusion

Implementation of DRGs in the field of obstetrics and gynecology among Korean tertiary hospitals led to reductions in the length of stay without increasing outpatient visits and readmission rates. The number of simultaneous surgeries requiring expensive operative instruments and emergency operations decreased after introduction of the DRGs.

Fee-for-service (FFS) is a payment model in which health care providers are paid for each service performed. Diagnosis-related-groups (DRGs) clinically mean groups of patients with similar clinical characteristics and resource consumption patterns who incur comparable costs. DRGs provide a flat per-discharge payment that varies based on diagnosis, severity, and the procedures performed. In this payment system, health care providers seek efficiency in order to receive more rewards from flat costs.

The Republic of Korea (Korea) introduced socialized health insurance in 1977, and achieved nationwide coverage by 1989. Initially, the national health insurance program was based on an FFS system. In order to reduce the rapid growth rate of health expenditures, the government started a pilot DRG program for several diseases in clinics and smaller hospitals. It resulted in reduced medical costs and hospital stays without negative effects on medical quality in terms of complications and reoperations.1 However, Korea still experienced high growth in health expenditures of around 8.6% per year from 2000 to 2009 under the FFS system, while that of other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries was 4.0%.2

With positive results from the pilot program, additional DRGs were implemented for seven disease groups, including three surgeries in obstetrics and gynecology for tertiary hospitals, mainly large academic hospitals, on July 1, 2013. By adopting this new payment system, these hospitals changed their clinical practice patterns, which affected costs and the quality of health care. Several studies demonstrated a consequent reduction in health care costs and length of hospital stay.34 However, concerns regarding care quality were raised while adopting the new payment system.

Several studies have evaluated the effects of DRGs on medical costs and care quality in different countries and in various medical fields, such as appendectomy, inguinal hernia, and cataract surgery.56 However, no study has demonstrated the effect of DRGs on the quality of hospital care in the field of obstetrics and gynecology, specifically with regard to cesarean sections (C-secs), hysterectomies, and adnexectomies. We examined whether a DRG payment system reduced the quality of hospital care and changes in clinical practice patterns among tertiary hospitals in the field of obstetric and gynecologic surgery by examining data on length of hospital stay, spillover, readmission within 30 days, and the number of simultaneous surgeries using National Health Insurance Service claims data from January 2012 to December 2014. We did not examine medical costs because the national hospital claim data did not include costs for uninsured medical services prior to the implementation of DRGs.

The present study was conducted as a retrospective observational cohort study. We examined 43 tertiary hospitals that adopted the payment system of DRGs on July 1, 2013. At this time, C-secs, hysterectomies, and adnexectomies were evenly performed across tertiary hospitals in Korea. In addition, primary or secondary medical institutions could transfer patients to the tertiary hospitals when surgical complications arose. Such data were omitted. Supplementary Table 1 (only online) presents the hospital lists included in the present study.

We used the National Health Insurance Service claim data collected from January 2012 to December 2014 for patients who were admitted to these hospitals and were scheduled to undergo C-secs, hysterectomies, or adnexectomies. The claims for surgical procedures were identified by the Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) codes from the National Health Insurance claim database. Supplementary Table 2 (only online) shows the EDI codes used to extract medical information.

The present study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital in 2016 (NHIMC 2016-03-009). Each EDI code was subdivided by procedure difficulty.

To examine the effects of the DRG-based payment system, we evaluated several variables related to medical care quality, including the total number of operations, number of emergency operations, length of stay, spillover, readmission rate, and number of simultaneous operations. We did not consider the patients' clinical characteristics due to limitations in the data. Length of stay was measured using admission and discharge dates. Spillover was defined as an individual visiting an outpatient facility within 50 days post operation. This timeline was chosen because cesarean patients usually have a six-week postpartum visit, and most post-operation complications occur within 50 days. We used readmission rates within 30 days post discharge because most instances of perioperative mortality and morbidity occur during this period, according to a previous study.7

Under the FFS payment system, examinations that are performed in the emergency room (ER) are reimbursed. However, under the DRG payment system, they could not be reimbursed. Therefore, we assumed that the medical service provider would avoid surgeries for patients admitted from an ER. As a result, we compared the number of surgeries for patients admitted from an ER using DRGs within the FFS system.

A myomectomy or an adnexectomy could be performed along with a C-sec as a co-surgery. Surgery for stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse (POP) could be performed with a hysterectomy as a simultaneous surgery. Until 2014, co-surgery could not be reimbursed under the DRG payment system in tertiary hospitals. Therefore, these medical costs could not be reimbursed from July 2013 to December 2014. Therefore, we assumed that if the health care provider pursued excessive profits, the number of simultaneous surgeries would decrease, while the total number of adnexectomies would increase. We examined the changes in the number of simultaneous surgeries before and after the introduction of DRGs. For the analysis, we selected the patients who underwent hysterectomy under the diagnosis of POP (Korea Classification of Diseases; N81.2, N81.3, N81.4, N81.9) and examined the number of POP surgeries, including colporrhaphy, colpopexy, transobturator tape (TOT), and transvaginal tape (TVT) procedures, in these patients. In cases where severe pelvic adhesion was expected, some surgeons placed prophylactic ureteral stents before surgery to prevent ureteral injury during the surgical procedure. However, prophylactic ureteral stent placement cannot be reimbursed under DRGs. Therefore, we examined changes in the number of prophylactic ureteral stent placements (EDI code: R3261, R3262, R3263, R3264) before hysterectomies.

There are several treatment options for postpartum bleeding, such as balloon tamponade (EDI, L200500), uterine artery embolization (EDI, M6644), and hysterectomy (EDI, R4507, R4508, R4509, R4510, R5001). Postpartum bleeding is diagnosed by the clinicians who deliver babies. Because measuring the amount of postpartum hemorrhage is difficult, the diagnosis of postpartum bleeding is subjective. If the clinician adopts the balloon tamponade, uterine artery embolization, or hysterectomy options during delivery, the whole delivery procedure can be reimbursed through the FFS system instead of DRGs. Therefore, we assumed that clinicians may prefer additional treatment for postpartum hemorrhage to avoid DRGs. We examined the number of these treatment options for postpartum hemorrhage before and after the introduction of DRGs.

In Korea, a hysterectomy performed due to the diagnosis of carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix, also known as a Type I hysterectomy, is reimbursed with FFS, while a hysterectomy performed due to the diagnosis of benign gynecologic disease is reimbursed with DRGs. However, hysterectomies and perioperative procedures including uterine fibroids and carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix do not differ, regardless of the diagnosis. We hypothesized that we could evaluate the effects of the payment system on medical behavior if we examined the length of hospitalization for hysterectomies according to the diagnosis and the payment system. Therefore, we examined the length of stay of patients undergoing hysterectomies under the diagnosis of carcinoma in situ.

The distribution of each categorical variable was examined using an analysis of frequencies and percentages, and chi-square test were performed to examine the association between variables and the DRG payment system. Student's t-tests were performed to compare the average values and standard deviations for continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC, USA). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

After the introduction of the DRG payment system, the average length of stay for those undergoing C-secs, hysterectomies, and adnexectomies in obstetrics and gynecology departments significantly decreased (8.0±6.9 vs. 6.0±2.3 days, p<0.001, 7.4±3.5 vs. 6.4±2.7 days, p<0.001, 6.3±3.6 vs. 6.2±4.0 days, p<0.001, respectively) (Table 1). For all surgeries, spillover increased slightly after the introduction of the DRGs. However, there was no statistical significance in this difference (Table 1). On the other hand, readmission rates decreased after introducing the DRGs (C-sec, 2.13% vs. 1.19%, p<0.001; hysterectomies, 4.51% vs. 3.05%, p<0.001; adnexectomies, 4.77% vs. 2.65%, p<0.001).

We examined the number of emergency hysterectomies and adnexectomies (Table 2). From January 2012 to June 2013, 612 patients (3.33%) and 8383 patients (16.74%) were admitted from the ER and underwent hysterectomies and adnexectomies, respectively. Since the DRG payment system was introduced, 377 (2.25%) and 4788 (13.31%) cases of emergency hysterectomies and adnexectomies were conducted, respectively. Thus, the proportion of emergency operations out of the total number of operations performed significantly decreased with regard to hysterectomies and adnexectomies (3.33% vs. 2.25%, 16.74% vs. 13.31%, all p<0.001).

We also examined changes in the number of simultaneous surgeries, including myomectomies or adnexectomies during C-secs and POP surgeries during hysterectomies (Table 2). There was no difference in the number of co-surgeries during C-secs between the DRGs and FFS systems. Moreover, 101 (0.51%) myomectomy and 122 (0.62%) adnexectomy cases were performed with C-secs between January 2012 and June 2013, while 117 (0.61%) myomectomy and 132 (0.68%) adnexectomy cases were conducted between July 2013 and December 2014.

Among patients who underwent hysterectomies, 2081 and 1867 were diagnosed with POP or stress urinary incontinence during the FFS and DRG periods, respectively (Table 2). Of those, a colporrhaphy was performed for 445 (21.35%) and 431 (23.09%) cases, respectively. There was no significant difference based on the payment system. During the FFS period, colpopexy and TOT/TVT procedures were performed for 195 (9.37%) and 201 (9.66%) cases, respectively. On the other hand, 124 (6.64%) colpopexy and 59 TVT/TOT (3.16%) procedures were performed under DRGs. Both colpopexies and TOT/TVT procedures decreased significantly according to the payment system. Prophylactic ureteral stent placements before hysterectomies also significantly decreased due to the introduction of DRGs (360 cases, 1.96% vs. 188 cases, 1.12%, p<0.001) (Table 2).

Next, we examined the number of treatments involving balloon tamponade, uterine artery embolization, or hysterectomy procedures for postpartum hemorrhage (Table 2). The total number of patients who received additional treatment because of postpartum hemorrhage increased (542 cases, 2.72% vs. 619 cases, 3.21%, p=0.0042). Balloon tamponade and uterine artery embolization procedures increased, while cesarean hysterectomies decreased (110 cases, 0.55% vs. 180 cases, 0.93%, p<0.001; 271 cases, 1.36% vs. 313 cases, 1.62%, p=0.0315; 161 cases, 0.81% vs. 126 cases, 0.65%, p=0.041, respectively).

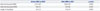

Hysterectomies with the diagnosis of carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix were exceptions for DRGs. Therefore, the surgical procedures were reimbursed with FFS during the whole study period. We examined the changes in the length of stay for those who underwent hysterectomies with the diagnosis of cervical carcinoma in situ after the introduction of the DRGs. Though the DRG payment system did not influence the surgeries, there was a significant decrease in the length of the hospital stay after the introduction of DRGs (6.6±3.2 vs. 5.8±2.4 days, p<0.001) (Table 3). In addition, the total fees and deductibles also decreased with statistical significance after the introduction of DRGs (2177±817 vs. 2078±971 thousand KRW, 136±76 vs. 124±89 thousand KRW, respectively, p<0.001).

After the implementation of the national health insurance system, tertiary hospitals as medical service providers had been reimbursed by the regulated FFS system until July 2013, when the DRG payment system was introduced. Under the FFS system, health care providers attempted to increase the volume and intensity of medical services to obtain a greater profit margin. Under the DRGs, medical service providers had to adopt various strategies to save on medical costs while maintaining the high-quality health care; hence, they had to change their clinical practice patterns to maximize incentives. In reality, there were concerns regarding care quality resulting from the pursuit of excessive profits, as well as moral hazards for patients who demanded unnecessary hospitalizations when DRGs were initially implemented. Under the DRG system, reimbursements differed by the average length of stay even though the amount was fixed. In addition, health care providers attempted to compensate for any decrease in profit due to the DRG system by discharging patients earlier than expected. To maintain the quality of medical care, hospitals would increase the number of outpatient visits instead of increasing the length of hospital stays. This could lead to the unintended results of increasing readmission rates due to operative complications. Furthermore, patients had no motivation to be discerning in their choices of health care services. The natural tendency would be for the patients to overconsume health care services, regardless of whether they would actually improves their health.

Past reports have revealed that inappropriate premature discharges increased under the DRG system in order to pursue excessive hospital profits.8910 Additionally, the use of outpatient departments and other nursing care facilities increased after discharges,10111213 while readmission rates increased,8141516 and health care quality dropped.41718 However, Epstein, et al.19 reported that DRGs decreased the length of stay without increasing the readmission rate or the number of outpatient visits in the United States. Meanwhile, Kim, et al.20 examined the impact of the new payment system on laparoscopic appendectomies in Korea and reported that the implementation of the DRGs decreased the total medical cost and the length of hospital stay without increasing medical complications and readmission rates. Another appendectomy study in Korea showed that the mandatory implementation of DRGs in July 2013 resulted in reduced length of stay and readmission rates for appendectomy management, as well as in an expansion of outpatient services.6

It must be noted that these studies were performed in different medical fields or in comprehensive medical areas. No prior report has presented the effects of the introduction of DRGs on length of stay, spillover effects, and readmission rates in obstetrics and gynecology departments in Korea. Our study demonstrated that length of hospital stay decreased without increasing readmission rates and spillover effects post obstetrics and gynecological surgeries. These results revealed that medical providers in Korea adopted DRGs by reducing length of stay in order to increase medical profits. However, reduced length of stay did not affect outpatient visits and readmission rates.

Prophylactic ureteral stent insertions also decreased. Although the total number of patients who were diagnosed with postpartum hemorrhage increased, most increases resulted from the increase in the balloon tamponade procedure, which is less invasive and better for fertility preservation. This suggests that one of the concerns that was raised at the beginning of the DRG payment system–unnecessary long-term hospitalization at the request of the patient–was not serious enough to affect medical efficiency. In other words, the pursuit of economic profits health care providers was not too excessive as to reduce the quality of medical care.

DRGs also affected the length of stay for hysterectomies performed due to a diagnosis of carcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix, which was reimbursed with the FFS but not with DRG. This was primarily due to a focus on medical efficiency rather than on profits by the medical providers by learning of the effects of DRGs. Our study revealed that total fees and deductibles in type I hysterectomies also decreased after the introduction of DRGs, which is believed to have led to a decrease in medical expenditures even though type I hysterectomies are reimbursed as an FFS.

Examining changes in the number of co-surgeries, we discovered that the number of those requiring expensive medical equipment decreased, while the number of those that did not remained the same. Patients diagnosed with POP required a colpopexy to prevent vault prolapse after a hysterectomy. Therefore, a hysterectomy and a colpopexy with a medical mesh are preferred for patients with high risk of recurrence for vault prolapse.21 TOT/TVT procedures can be performed with a hysterectomy as a co-surgery for patients with uterine fibroids and stress urinary incontinence. Expensive medical mesh, which costs about 100000 KRW (about 110 US dollars), is required for TOT/TVT surgical procedures, but it cannot be reimbursed when a patient undergoes co-surgery. However, colporrhaphy can be conducted using simple absorbable suture materials. A myomectomy or an adnexectomy during a C-sec can also be performed with inexpensive surgical suture materials. Combining these findings, we deduced that the DRG payment system causes health care providers to avoid co-surgeries that require expensive medical equipment, such as medical mesh, to maximize profits. However, this adverse effect of DRGs on cosurgeries is limited to surgeries that include substantial additional costs. Appropriate co-surgeries will lessen the burden upon patients undergoing multiple surgeries. Improvements to the DRG payment system (e.g., compensating additional costs for expensive medical instruments) are needed to alleviate any tendency to avoid a co-surgery.

Our results showed that the number of surgeries from the ER decreased. Under DRGs, expensive medical services including computed tomography and ultrasonography cannot be reimbursed. This might lead to a decreased number of emergency surgeries under DRGs. This policy may have both pros and cons with regard to medical quality. Medical providers should develop a triage system for distinguishing priority patients from the ER to maximize profits. The advantage of this change would be to avoid unnecessary surgeries and utilize medical resources efficiently. However, a patient who requires an emergency surgery may miss a crucial time window. Therefore, additional research is required to evaluate whether a decreased number of emergency surgeries in the field of obstetrics and gynecology has a positive effect on medical quality.

The number of adnexectomies in tertiary hospitals has decreased since the DRG payment system was introduced. The government decided to increase the reimbursement rate for hospitals to adopt the new payment system efficiently without opposition from medical service providers. This might have encouraged general hospitals to perform gynecological surgeries especially adnexectomies because they are relatively easy. Therefore, the number of adnexectomies performed in tertiary hospitals decreased.

Our study had several strengths. First, we used National Health Insurance Service claim data that included a large sample of patients and hospitals. Second, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the effect of DRGs on the quality of health care across three disease groups within obstetrics and gynecology. Third, our results highlight the pros and cons of DRGs and could suggest improvements to current DRGs in the field of obstetrics and gynecology.

However, there are also several limitations of our study. First, we did not use individual subject data for analysis in the study. Therefore, further adjustment according to disease severity could not be performed with obtained information. This may result in ecological fallacy in interpreting the results. Second, we did not measure the effects of DRGs on health care costs in the field of obstetrics and gynecology because the national hospital claim data did not include the costs for uninsured medical materials in FFS. Third, we examined the claims data of only 43 tertiary hospitals that mandatorily participated in the DRGs by July 1, 2013. These hospitals did not represent the national as a whole. Kim, et al.5 examined the association between the effects of market competition and quality of care following the introduction of the DRGs. In their study, an observational analysis was performed using national health insurance claim data from 2011 to 2014. They categorized market competition in order to measure its different effects, and their results showed that the length of stay, readmission rate, and number of outpatient visits differed based on market competition. Fourth, we did not analyze laparoscopic surgeries and laparotomies separately, which are different in terms of surgical methods, patient complications, and side effects. Lastly, we considered a short implementation period of DRGs (18 months). Further studies are needed to examine the effects of DRGs on the quality of clinical care and behavior within obstetrics and gynecology departments over the long term.

In conclusion, the implementation of DRGs in the field of obstetrics and gynecology in Korea has led to significant reductions in the length of stay without increasing outpatient visits and readmission rates. Additionally, simultaneous surgeries requiring expensive operative instruments and the number of surgeries in the ER decreased after the introduction of DRGs. Further studies are required to evaluate the effects of these changes on the quality of medical care. Regular evaluation of the DRGs will be necessary to improve medical quality and health care efficiency under DRGs.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

Impact of the DRG-Based Payment on Length of Stay, Spillover, and Readmission

Table 2

Impact of the DRG-Based Payment on Simultaneous Surgery

Table 3

Change in the Fee and Length of Stay of Type I Hysterectomy in Carcinoma in situ of Uterine Cervix before and after DRG

| Before DRG (n=1075) | After DRG (n=957) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Fee (thousand KRW) | 2177±817 | 2078±971 | <0.001 |

| Deducible (thousand KRW) | 136±76 | 124±89 | <0.001 |

| Length of stay (days) | 6.6±3.2 | 5.8±2.4 | <0.001 |

References

1. Kwon S. Payment system reform for health care providers in Korea. Health Policy Plan. 2003; 18:84–92.

2. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a glance 2011: OECD indicators. 6th ed. Paris: OECD Publishing;2011.

3. Choi JW, Jang SI, Jang SY, Kim SJ, Park HK, Kim TH, et al. The effect of mandatory diagnosis-related groups payment system. Health Policy Manag. 2016; 26:135–147.

4. Hamada H, Sekimoto M, Imanaka Y. Effects of the per diem prospective payment system with DRG-like grouping system (DPC/PDPS) on resource usage and healthcare quality in Japan. Health Policy. 2012; 107:194–201.

5. Kim SJ, Park EC, Kim SJ, Han KT, Han E, Jang SI, et al. The effect of competition on the relationship between the introduction of the DRG system and quality of care in Korea. Eur J Public Health. 2016; 26:42–47.

6. Kim TH, Park EC, Jang SI, Jang SY, Lee SA, Choi JW. Effects of diagnosis-related group payment system on appendectomy outcomes. J Surg Res. 2016; 206:347–354.

7. Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Gawande AA, Jha AK. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:1134–1142.

8. Carroll NV, Erwin WG. Effect of the prospective-pricing system on drug use in Pennsylvania long-term-care facilities. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990; 47:2251–2254.

9. Kahn KL, Rubenstein LV, Draper D, Kosecoff J, Rogers WH, Keeler EB, et al. The effects of the DRG-based prospective payment system on quality of care for hospitalized Medicare patients. An introduction to the series. JAMA. 1990; 264:1953–1955.

10. Fitzgerald JF, Fagan LF, Tierney WM, Dittus RS. Changing patterns of hip fracture care before and after implementation of the prospective payment system. JAMA. 1987; 258:218–221.

11. Guterman S, Dobson A. Impact of the medicare prospective payment system for hospitals. Health Care Financ Rev. 1986; 7:97–114.

12. Sloan FA, Morrisey MA, Valvona J. Medicare prospective payment and the use of medical technologies in hospitals. Med Care. 1988; 26:837–853.

13. Wood JB, Estes CL. The impact of DRGs on community-based service providers: implications for the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1990; 80:840–843.

14. Weinberger M, Ault KA, Vinicor F. Prospective reimbursement and diabetes mellitus. Impact upon glycemic control and utilization of health services. Med Care. 1988; 26:77–83.

15. Leibson CL, Naessens JM, Campion ME, Krishan I, Ballard DJ. Trends in elderly hospitalization and readmission rates for a geographically defined population: pre- and post-prospective payment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991; 39:895–904.

16. Gay EG, Kronenfeld JJ. Regulation, retrenchment--the DRG experience: problems from changing reimbursement practice. Soc Sci Med. 1990; 31:1103–1118.

17. Brizioli E, Fraticelli A, Marcobelli A, Paciaroni E. Hospital payment system based on diagnosis related groups in Italy: early effects on elderly patients with heart failure. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1996; 23:347–355.

18. Choi J. Perspectives on cost containment and quality of health care in the DRG payment system of Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2012; 55:706–709.

19. Epstein AM, Bogen J, Dreyer P, Thorpe KE. Trends in length of stay and rates of readmission in Massachusetts: implications for monitoring quality of care. Inquiry. 1991; 28:19–28.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download