Abstract

Purpose

To estimate long-term outcomes after treatment modification in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) treated with entecavir (ETV) and telbivudine (LdT).

Materials and Methods

The study enrolled 131 nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA)-naïve CHB patients treated with ETV or LdT. During the 3-year study, NA treatment history including the incidence, the type of treatment modification, reasons for the modification, and overall complete virologic response (CVR) rate were retrospectively evaluated using the patients' medical records.

Results

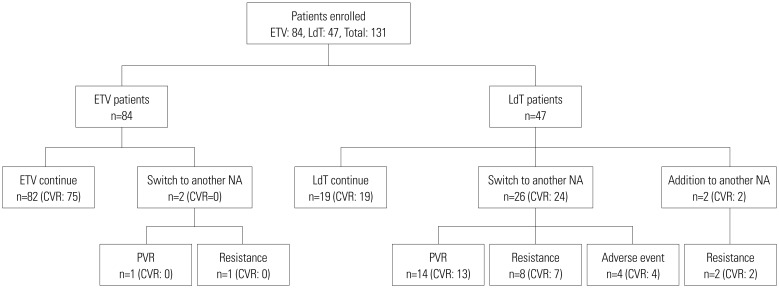

Among the 131 patients, 84 and 47 were initially treated with ETV and LdT, respectively. During the course of 3-year study, 82 patients in the ETV group (97.6%) maintained initial treatment whereas only 19 in the LdT group (40.4%). In the LdT group, 26 patients (92.9%) switched to another NA and another NA was added in 2 (7.1%) patients. An assessment of the CVR rate at 3 years, including treatment modification, showed that 89.3% and 95.7% of patients in the ETV and LdT groups, respectively, had undetectable serum hepatitis B virus DNA levels (p=0.329). Among LdT patients with treatment modification, the cumulative incidence rate of a CVR for rescue therapy was significantly higher in the tenofovir than in the ETV group (p=0.009).

Among the antiviral agents available for treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients, entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir (TDF) exhibit potent antiviral effects and low resistance rates.123 Telbivudine (LdT) also deserves consideration as an initial antiviral agent due to its relatively strong antiviral effect and reports of efficacy when used as an initial treatment for appropriate patient groups based on the roadmap treatment concept.45 However, LdT is currently not recommended as a first-line drug because of concern over possible treatment failure in patients with a suboptimal response and the higher resistance compared to ETV and TDF.6 Nonetheless, LdT has several advantages including its cost and usability in clinical practice. According to a recent report,789 in patients with a suboptimal response to LdT or adefovir (ADV), rescue therapy with ETV produced a high complete virologic response (CVR) rate. Among those who did not respond to a nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA) or who had mutant resistance to LdT, the efficacy of TDF rescue therapy was outstanding.1011121314151617 Thus, these studies suggest that, when the effects of initial treatment with LdT are insufficient, treatment with a rescue antiviral agent may be successful. However, in patients with CHB treated with LdT, little is known about the treatment modification rates or long-term outcomes in real world experience.

Therefore, in this 3-year retrospective study, we analyzed the virologic and biochemical responses in patients initially treated with LdT, including those who were maintained on the initial LdT treatment and those who required treatment modification for various reasons. The responses of these patients and those in an ETV initial treatment group were compared.

In this retrospective study, the data from 131 antiviral-treatment-naïve Korean CHB patients who started antiviral therapy with 0.5 mg ETV or 600 mg LdT between February 2007 and June 2012 in the National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital were analyzed. Patients with electronic medical records who charted a 3-year clinical course of their disease and its treatment were included. Patients who previously received an oral NA or interferon, those with co-infection by hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, or human immunodeficiency virus, and those with decompensated liver cirrhosis were excluded. The antiviral agent was selected according to the physician's discretion and patient's preference. Baseline patient data, including age, gender, medical history, hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), were evaluated. Patients were followed up every 3 months for clinical assessments including compliance, adverse effects of the NA, and serum levels of HBV DNA, AST, and ALT. Treatment modification occurrence, type of treatment modification (switch to another NA, addition of another NA, or dose modification), reason for treatment modification [partial virologic response (PVR), viral resistance, and adverse event induced by the NA], CVR occurrence, and ALT normalization were investigated.

The primary endpoints were a CVR at 3 years and cumulative incidence of a CVR during 3 years of treatment. Secondary endpoints were treatment maintenance at 3 years, types of and reasons for treatment modification, rate of ALT normalization, and the cumulative incidence of a CVR to rescue antiviral therapy.

A CVR was defined as a decrease in serum HBV DNA to <20 IU/mL, and a PVR defined as a decrease in HBV DNA >1 log10 IU/mL but still detectable HBV DNA after 6 months of antiviral therapy. ALT normalization was defined as a decrease in serum ALT to <40 IU/L. Viral breakthrough was defined as an HBV DNA increase >1 log10 IU/mL from the nadir level during antiviral treatment and confirmation of a resistance mutation by genetic analysis. Treatment maintenance was defined as the maintenance of initial antiviral agent for 3 years without treatment modification, and treatment modification was defined as a change in treatment including a switch to or the addition of another antiviral agent.

Continuous data were analyzed with Student's t-test and are presented as mean±standard deviation or as a proportion. Categorical variables were analyzed in a chi-square test or with Fisher's exact test. The tests were used to identify differences between the ETV and LdT groups in the CVR and treatment maintenance rates at 3 years. The cumulative incidence of a CVR during 3 years of treatment, ALT normalization during 3 years of treatment, and a CVR after rescue therapy were assessed using Kaplan-Meier method. The difference between cumulative curves was evaluated using the log-rank test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All of the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Approval for our study, including research conducted within the database, was obtained from the Ethics Committee of National Health Insurance Ilsan Hospital (IRB No. 2015-02-001).

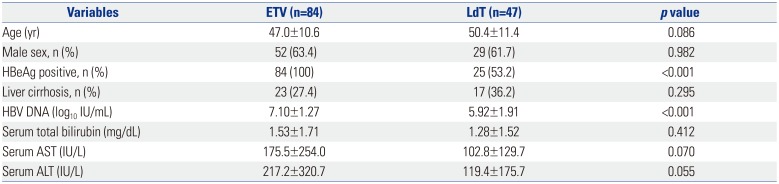

Among the 131 patients enrolled in the study, 84 were treated with ETV and 47 with LdT (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 47.0±10.6 years in the ETV group and 50.4±11.4 years in the LdT group (p=0.086). The proportion of males in the two groups was 63.4% and 61.7%, respectively; the difference was not significant (p=0.982). There were also no statistically significant differences in age, gender, liver cirrhosis, initial serum AST, initial serum ALT, and initial serum total bilirubin between the ETV and LdT groups. However, patients in the ETV group had higher serum HBV DNA levels than those in the LdT group (7.10±1.27 log10 IU/mL vs. 5.92±1.91 log10 IU/mL, p<0.001) and higher proportion of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive patients than those in the LdT group (100% vs. 53.2%, p<0.001).

Patients in the ETV group had a significantly higher rate of treatment maintenance during 3 years of the study than patients in the LdT group (97.6% vs. 40.4%, p<0.001).

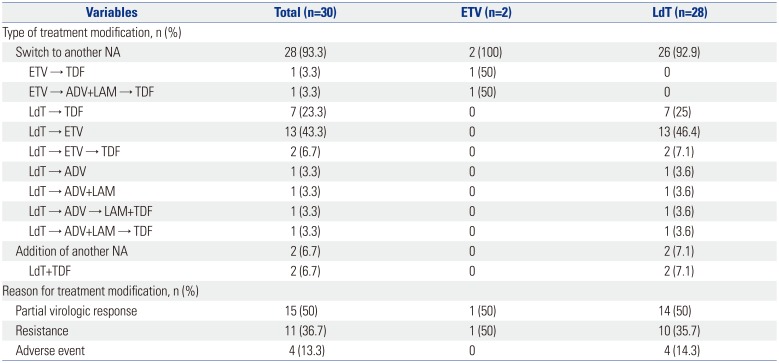

Treatment modification was required in 30 (22.9%) patients: only 2 (2.4%) in the ETV group, but 28 (59.4%) in the LdT group. In the ETV group, treatment modification consisted of a switch to another NA for both patients. The patient with a PVR was switched to TDF, and the patient with viral resistance was switched first to ADV and lamivudine combination therapy, and then to TDF. In the LdT group, a switch to another NA was required in 26 (92.9%) patients, and NA was added in 2 (7.1%) other patients (Table 2). In the LdT group, the reasons for treatment modification were a PVR in 14 patients, resistance in 10 patients, and an adverse event in 4 patients (Fig. 1). Among the 10 patients with resistance, 8 had M204I mutations and 2 had L80I and M204I mutation. The specific types of drug switches and additions are summarized in Table 2.

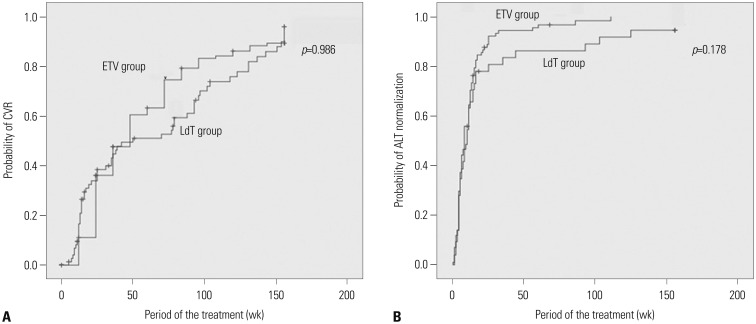

In the ETV and LdT groups, 75 of 84 (89.3%) and 45 of 47 (95.7%) patients, respectively, including those who required treatment modification, demonstrated a CVR at the year 3. The difference between the two groups was not significant (odds ratio=0.370, p=0.326). The cumulative incidence rate of a CVR was also not significantly different (p=0.986) (Fig. 2A). The ETV and LdT groups did not differ in their biochemical responses, as demonstrated by the cumulative incidence rate of ALT normalization (p=0.178) (Fig. 2B).

In the ETV group, two patients switched from ETV to another antiviral agent (Table 2). In both patients, the switch was implemented 30 months after ETV initiation, but a CVR was not achieved until 3 years after the initiation. In the LdT group, 14 patients required treatment modification due to a PVR (Fig. 1). Three of these patients were switched to TDF, and all of them achieved a CVR. A total out of 9 of 14 patients were switched to ETV, 8 of whom achieved a CVR. In 2 of the 14 patients, two drug switches were necessary (LdT→ETV→TDF). Both of the patients were treated with ETV for 12 months but were switched back to TDF because of a PVR. One of the patients had a CVR 16 months after switching to TDF, and the other patient had a CVR at 3 months.

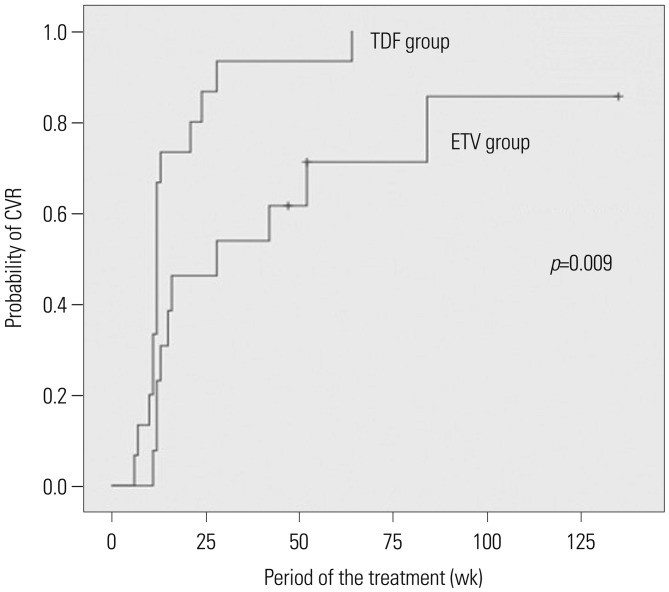

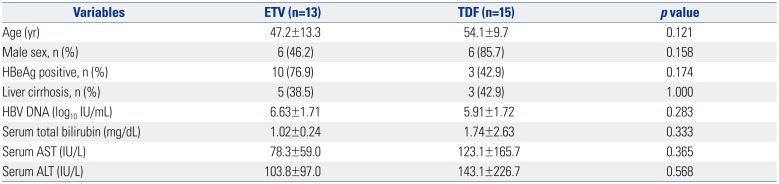

Ten patients in the LdT group required treatment modification due to resistance. Two of these patients were switched to ADV monotherapy or combination therapy; one of these patients achieved a CVR. Eight of ten patients were switched to TDF monotherapy or combination therapy, and all of them achieved a CVR. In the LdT group, 4 patients required treatment modification due to an adverse event (2 with myopathy and 2 with abdominal pain). After a switch to ETV, all of them achieved a CVR. A comparison of the virologic response to ETV and TDF as rescue therapies showed that all 15 patients who received TDF rescue therapy and 10 of 13 patients who received ETV rescue therapy achieved a CVR (Table 3). The cumulative CVR incidence following rescue therapy was significantly higher in the TDF group than in the ETV group (p=0.009) (Fig. 3).

A favorable outcome was expected with LdT treatment because of its relatively strong antiviral effect. It is particularly effective for patients with a low baseline HBV DNA level (HBeAg-positive patients with baseline HBV DNA <9 log10 copies/mL, HBeAg-negative patients with baseline HBV DNA <7 log10 copies/mL, and ALT >2×upper limit of normal).5 Therefore, long-term treatment with LdT should be considered in appropriate patients. In fact, a recent meta-analysis that compared the efficacy of ETV with that of LdT reported similar virologic and biochemical responses with the two drugs.51819

However, LdT is not recommended as a first-line antiviral agent for CHB because of relatively high risks of treatment failure due to resistance and a PVR. Instead, ETV and TDF are currently recommended as first-line antiviral agents for CHB, based on their outstanding antiviral effects and very low rates of resistance despite long-term use. ETV and TDF have also been evaluated as rescue therapies. In a recent study,7 rescue therapy with ETV resulted in a CVR in 80% of patients who had a PVR to LdT; for patients who did not respond to a NA, rescue therapy with TDF resulted in a CVR in 90%.10 Some studies have also shown that, TDF, when used as a rescue therapy, has excellent antiviral activity in most patients who develop antiviral resistance to LdT.11121314151617 However, little is known about treatment modification rates and long-term outcomes after treatment modification in patients with CHB treated with LdT in real world experience.

In the present study, we compared the virologic and biochemical responses (including after treatment modification) obtained in patients treated with LdT versus ETV as the first-line antiviral agent during a 3-year period. The initial treatment maintenance rate at 3 years was significantly higher in the ETV than in the LdT group (97.6% vs. 40.7%), similar to the results reported by Chien, et al.6

In the ETV group, most patients maintained their initial antiviral agent during the 3-year treatment period, whereas, there was a relatively high rate of treatment modification in the LdT group because of a partial response, resistance, or adverse reaction. However, an analysis of data, including a CVR after treatment modification, failed to show a significant difference between the two groups during the 3 years in the CVR rate, the cumulative incidence of a CVR, or the cumulative incidence of ALT normalization. This could be attributed to the effects of the rescue antiviral agent. Roughly 90% of the study patients who failed to show a complete response to a first-line antiviral agent achieved a CVR after switching to a rescue antiviral agent. It is thus possible that a CVR can be obtained following effective treatment modification.

On the other hand, a comparison of the efficacy of TDF and ETV as rescue therapies revealed that 100% of patients who received TDF achieved a CVR, compared to 77% of patients treated with ETV. For all of the patients who had a PVR to ETV rescue therapy, TDF rescue therapy yielded a CVR, which demonstrated greater efficacy of TDF than ETV as a rescue antiviral agent, as reported in a recent study.72021 We were unable to assess the factors affecting the efficacy of ETV or TDF rescue therapy. However, these results were based on small-scale retrospective data. To compare ETV and TDF as a rescue therapy, clinical study with high quality of evidence is needed.

There are a few limitations to our study. First, because this study was conducted at a single center, the number of study patients was small; in addition, considering the nature of CHB treatment, a 3-year period is insufficient to fully determine the efficacy of an antiviral agent. Multicenter randomized controlled study is needed to confirm the efficacy of LdT therapy with treatment modification, but it is difficult in Korea. Second, many patients did not complete the 3-year follow-up, a shortcoming of the retrospective design of the study patients treated in real clinical practice. Finally, for a statistically valid comparison of the efficacy of rescue antiviral agents and a determination of the factors related to their efficacy, the number of cases was too small.

Nonetheless, our results showed significantly superior maintenance rate of ETV compared to LdT, although there were no differences in virologic or biochemical response at 3 years between patients initially treated with either drug, after rescue treatment modification. Therefore, LdT merits consideration as a first-line antiviral agent for CHB. When initial LdT treatment fails, TDF may be a more effective rescue antiviral agent than ETV.

References

1. Buti M, Tsai N, Petersen J, Flisiak R, Gurel S, Krastev Z, et al. Seven-year efficacy and safety of treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2015; 60:1457–1464. PMID: 25532501.

2. Idilman R, Gunsar F, Koruk M, Keskin O, Meral CE, Gulsen M, et al. Long-term entecavir or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate therapy in treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B patients in the real-world setting. J Viral Hepat. 2015; 22:504–510. PMID: 25431108.

3. Lampertico P, Chan HL, Janssen HL, Strasser SI, Schindler R, Berg T. Review article: long-term safety of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues in HBV-monoinfected patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016; 44:16–34. PMID: 27198929.

4. Zeuzem S, Gane E, Liaw YF, Lim SG, DiBisceglie A, Buti M, et al. Baseline characteristics and early on-treatment response predict the outcomes of 2 years of telbivudine treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009; 51:11–20. PMID: 19345439.

5. Wang Y, Thongsawat S, Gane EJ, Liaw YF, Jia J, Hou J, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous 4-year telbivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2013; 20:e37–e46. PMID: 23490388.

6. Chien RN, Peng CY, Kao JH, Hu TH, Lin CC, Hu CT, et al. Higher adherence with 3-year entecavir treatment than lamivudine or telbivudine in treatment-naïve Taiwanese patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014; 29:185–192. PMID: 24354995.

7. Lo AO, Wong VW, Wong GL, Chan HY, Cheung CM, Chan HL. Efficacy of entecavir switch therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with incomplete virological response to telbivudine. Antivir Ther. 2013; 18:671–679. PMID: 23462214.

8. Sheen E, Trinh HN, Nguyen TT, Do ST, Tran P, Nguyen HA, et al. The efficacy of entecavir therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with suboptimal response to adevofir. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011; 34:767–774. PMID: 21806648.

9. Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Brown A, Zoulim F, Mutimer D, Deterding K, et al. Entecavir treatment for chronic hepatitis B: adaptation is not needed for the majority of naïve patients with a partial virological response. Hepatology. 2011; 54:443–451. PMID: 21563196.

10. Huang M, Li X, Wu Y, Tao L, Jie Y, Li X, et al. [Efficacy of 48-week tenofovir disoproxil fumarate therapy in patients who were unresponsive to nucleoside-analogue treatments]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2014; 22:266–271. PMID: 25173224.

11. Lee YB, Jung EU, Kim BH, Lee JH, Cho H, Ahn H, et al. Tenofovir monotherapy versus tenofovir plus lamivudine or telbivudine combination therapy in treatment of lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015; 59:972–978. PMID: 25421484.

12. Choi K, Lee HM, Jun BG, Lee SH, Kim HS, Kim SG, et al. [Efficacy of tenofovir-based rescue therapy for patients with drug-resistant chronic hepatitis B]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2015; 65:35–42. PMID: 25603852.

13. Kim HJ, Cho JY, Kim YJ, Gwak GY, Paik YH, Choi MS, et al. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate therapy after multiple nucleos(t)ide analogue failure in chronic hepatitis B patients. Korean J Intern Med. 2015; 30:32–41. PMID: 25589833.

14. Kim BG, Jung SW, Kim EH, Kim JH, Park JH, Sung SJ, et al. Tenofovir-based rescue therapy for chronic hepatitis B patients who had failed treatment with lamivudine, adefovir, and entecavir. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 30:1514–1521. PMID: 25973716.

15. Lee S, Park JY, Kim DY, Kim BK, Kim SU, Song K, et al. Prediction of virologic response to tenofovir mono-rescue therapy for multidrug resistant chronic hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 2016; 88:1027–1034. PMID: 26538234.

16. Lim YS, Yoo BC, Byun KS, Kwon SY, Kim YJ, An J, et al. Tenofovir monotherapy versus tenofovir and entecavir combination therapy in adefovir-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients with multiple drug failure: results of a randomised trial. Gut. 2016; 65:1042–1051. PMID: 25800784.

17. Wang HM, Hung CH, Lee CM, Lu SN, Wang JH, Yen YH, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir in nucleos(t)ide analog-naïve and nucleos(t)ide analog-experienced chronic hepatitis B patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016; 31:1307–1314. PMID: 26758501.

18. Liang J, Jiang MJ, Deng X, Xiao Zhou X. Efficacy and safety of telbivudine compared to entecavir among HBeAg+ chronic hepatitis B patients: a meta-analysis study. Hepat Mon. 2013; 13:e7862. PMID: 24032045.

19. Zhang Y, Hu P, Qi X, Ren H, Mao RC, Zhang JM. A comparison of telbivudine and entecavir in the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients: a prospective cohort study in China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016; 22:287.e1–287.e9.

20. Lu L, Yip B, Trinh H, Pan CQ, Han SH, Wong CC, et al. Tenofovir-based alternate therapies for chronic hepatitis B patients with partial virological response to entecavir. J Viral Hepat. 2015; 22:675–681. PMID: 25417914.

21. Pan CQ, Hu KQ, Yu AS, Chen W, Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Response to tenofovir monotherapy in chronic hepatitis B patients with prior suboptimal response to entecavir. J Viral Hepat. 2012; 19:213–219. PMID: 22329376.

Fig. 1

Flow diagram of the 3-years study. ETV, entecavir; LdT, telbivudine; NA, nucleos(t)ide analogue; CVR, complete virologic response; PVR, partial virologic response.

Fig. 2

Cumulative incidence of CVR and ALT normalization in response to ETV and LdT including treatment modification. (A) Cumulative incidence of CVR in patients with CHB. (B) Cumulative incidence of ALT normalization in patients with CHB. CVR, complete virologic response; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ETV, entecavir; LdT, telbivudine; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Fig. 3

Cumulative incidence of a CVR according to ETV and TDF as rescue therapy in patients with initial telbivudine therapy. CVR, complete virologic response; ETV, entecavir; TDF, tenofovir.

Table 1

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B

Table 2

Treatment Modification in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Treated in a 3-Year Period

Table 3

Comparison of Patients Treated with ETV and TDF after Initial Telbivudine Treatment at Treatment Modification

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download