INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of heart failure (HF) increases with age. Lee, et al.

1 estimated the overall prevalence of HF in South Korea at 1.5% and increases from about 1.0% in adults aged 40–59 years to 5.5% in persons aged 60–60 years and to 12.6% among those aged ≥80 years. The number of patients primarily diagnosed with HF-specific International Classification of Disease, 10th edition (ICD-10) codes (I50, I50.1, and I50.9) increased from 109224 in 2011 to 121159 in 2015 in South Korea.

2 As the total number of people with HF has increased around the world with rapid aging populations, HF has been identified as a major public health and economic issue. In a number of studies investigating the economic burden of HF on the healthcare system, a 1–2% healthcare expenditure burden was attributed to HF in Europe and North America.

34 According to the statistics provided by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA), HF-related spending in the reimbursed service increased by 44.6% (62–89 billion won), and the annual cost per person grew by 30% from 2011 to 2015 for primary diagnosis of I50.x codes.

2 This cost is likely underestimated, because it was based on claims data derived from reimbursement and excluded secondary diagnoses and other ICD-10 codes of HF.

The European Society of Cardiology guideline defines chronic HF (CHF) as a syndrome in which patients have had stable HF that remains unchanged for more than 1 month, while it defines acute HF (AHF) as a rapid onset of new HF or acute decompensation of pre-existing CHF.

5 Hospital admission is generally needed to treat AHF, which is often recurrent, since it is not a single organ disease itself but a complex clinical syndrome with a progressive and cyclical decline. The main social and economic burden of HF is associated with hospital admission, and hospitalization accounts for up to 70% of total HF costs. A study published in 2012 showed that hospital costs related to admission accounted for roughly 85% of all costs.

678 Considering this evidence, many studies have aimed to identify risk factors of hospitalization and re-hospitalization, and most studies of healthcare cost have focused only on hospitalized HF patients and did not consider stable CHF patients. In South Korea, there are limited data regarding healthcare costs and utilization for patients with HF.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to estimate HF-related costs and resource utilization of patients with AHF or stable CHF and to identify risk factors contributing to HF-related costs per patient per year in Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

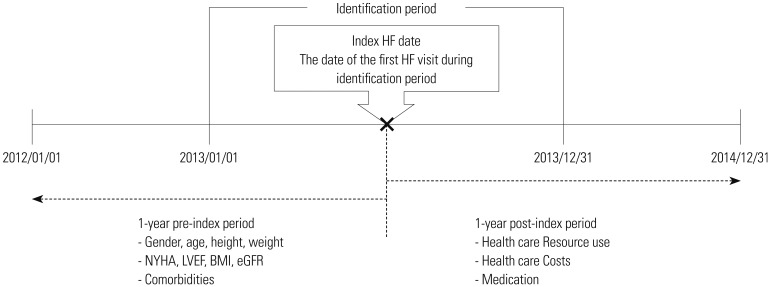

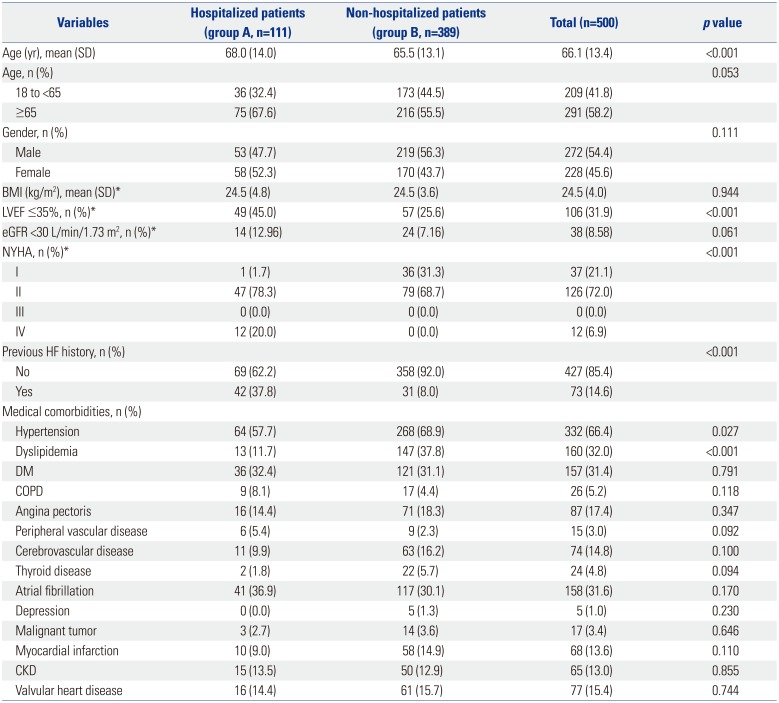

We conducted this retrospective observational cohort study at five tertiary hospitals and one general hospital in South Korea. Patients from tertiary referral hospitals comprised 88% of the entire study population. Patients enrolled in the study were 18 years or older and diagnosed with a HF-specific ICD-10 code (I50.0, I50.1, I50.9, I11.0, I13.0, I13.2) between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013 (

Fig. 1). An index date corresponding to the date of the first HF-related visit was assigned to each sample, and all subjects were followed for up to 1 year from the index date. Subjects were included if they had ≥one HF-related hospitalization or ≥two HF-related outpatient visits. Patients were excluded if they underwent chemotherapy or participated in an intervention clinical trial in the post-index period.

Stratification

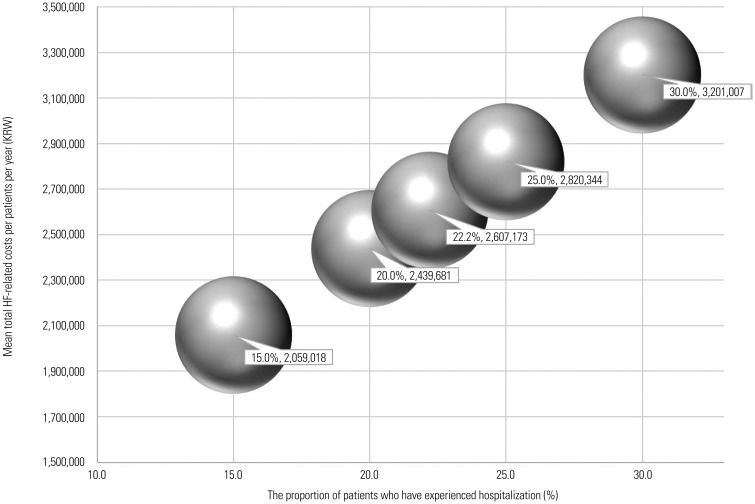

A well-chosen sample can be representative of the entire population. Several studies have found that hospitalization care is associated with greater cost and resource use in patients with HF. Patients were divided by hospitalization history during the post-index period and identified by stratified proportionate sampling, because the proportion of hospitalized patients leads to higher costs and resource utilization. Fifteen to 30 percent of the patients would likely be hospitalized according to claims database analyses using the HIRA National Patient Sample, within which we identified the study population.

Outcome measures

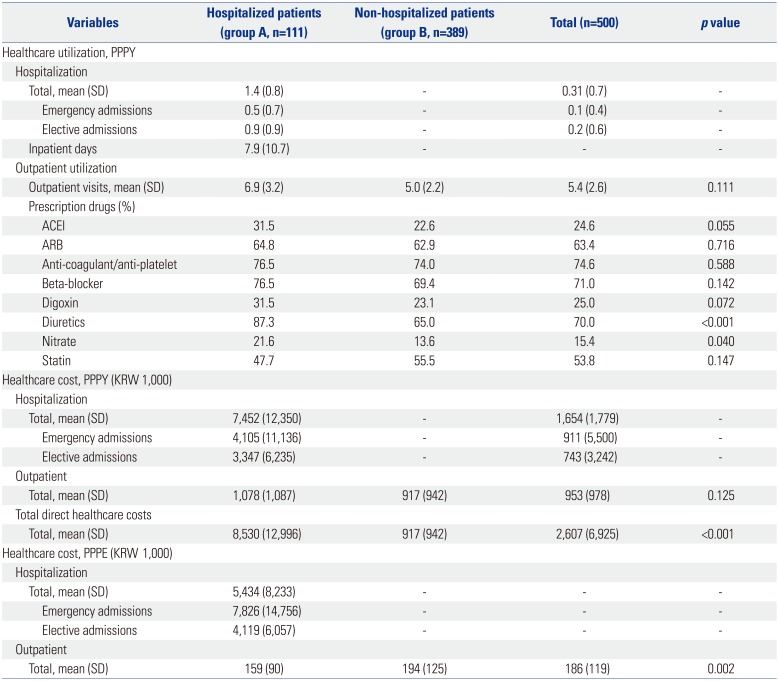

The endpoints of this study were HF-related healthcare costs and resource utilization during the 12-month analysis period following the index date. Outpatient visit, emergency department (ED) visit, hospitalization, and medications were assessed using both medical and prescription data. HF medication classes include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), anti-coagulants/anti-platelets, beta-blockers (BB), digoxin, diuretics, and nitrate. HF-related healthcare costs and resource utilization were calculated as per-patient per-year (PPPY) and per-patient per-event. Total healthcare costs comprised those covered by the National Health Insurance (NHI) fund and direct patient out-of-pocket (OOP) costs (both insured and non-insured).

We examined economic impacts in a variety of clinically relevant patient subgroups and conducted a subgroup analysis of costs by patient group focusing on patients who had at least one measure for the variables. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the six participating hospitals and Sungkyunkwan University.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed mean HF-related costs and utilization for 1 year per patient and compared them between groups A (hospitalized patients) and B (non-hospitalized patients) through mean differences. A generalized linear model with gamma distribution and log link function were used to evaluate the association between annual HF-related costs and risk factors. The model controlled for the effects of confounding variables, including age, sex, medical comorbidities, medication, and measures of baseline clinical characteristics by adjustment. The adjusted cost ratios (CRs) were reported for each regression.

p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and all analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT® version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). All costs were estimated in Korean won (KRW; US $1=1,170 KRW in 2016).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to assess healthcare costs and resource utilization among South Korean patients with AHF and stable CHF in a real-world population. We found that hospitalization contributes 63.4% of the total healthcare costs and that the mean annual total cost of hospitalized patients was 9.3 times higher than that of non-hospitalized patients (p<0.001).

To date, only HF-related costs in South Korea from the Korean Acute Heart Failure (KorAHF) Registry have been published.

9 This registry has focused on hospitalized AHF patients in 10 tertiary university hospitals with an estimated mean cost per admission of 7.7 million won and mean estimated LOS of 8 days. In the present study, the estimated average cost of admission was 5.4 million won (7.8 and 4.1 million won for ED and elective admissions, respectively). In relation to HF severity, Lee, et al.

9 reported that more than 80% of patients had severe dyspnea of New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV (41% respectively) in the KorAHF registry, whereas nearly 78% had NYHA class II and only 4 patients had NYHA class IV in our study. HF patients in KorAHF were considered to be more severe than patients in our study. This higher average admission cost per the KorAHF, compared to that observed in our study, may be attributable to differences in HF patient severity or comorbidities and the number of admissions via the ED.

HF patients often require hospitalization for acute clinical deterioration, despite their chronic condition, since their status is usually life-threatening and requires urgent treatment in the ED.

10 The rate of emergency admissions (35.7%) among all hospitalizations observed in the present study was considerably lower than the rate of 72% previously reported by the KorAHF registry. Related to the proportion of ED visits per year among total HF patients, there was a lower proportion in our study population, compared with the American Heart Association statistics (10.4% vs. 20%). Therefore, it is likely to lead to an underestimation of the average costs in our study, because ED visits are associated with increased healthcare costs. Furthermore, among hospitalized patients, only 55% were followed for up to 1 year from their index hospitalization, estimating an annual mean cost of KRW 9,088,886, which is 7% higher than those of total hospitalized patients.

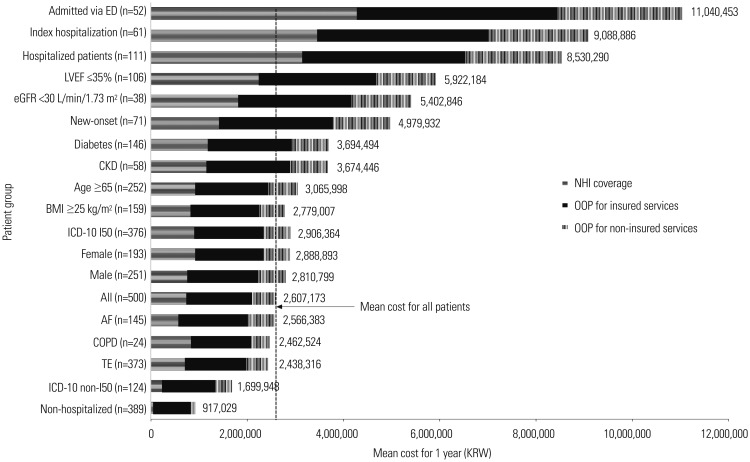

The mean annual costs for a patient with HF are estimated to be approximately KRW 2,607,173, with hospitalization, outpatient visits, and medication comprising 63.4, 14.8, and 21.7% of the costs, respectively. According to HF research costs, expenditures for hospital admissions account for approximately 47–69% of the total direct costs, consistent with the 63% noted in this study. Similarly, drug costs have been found to account for 16% of the total direct costs of HF in Ireland, 18% in the UK, and 18% in Sweden, findings that are consistent with the 21.7% in of our study.

11

Based on HF management guidelines, ACEI, ARB, BB, digoxin, and diuretics are the most commonly prescribed drugs, and the use of first-line ACEI is recommended.

1213 Patients in European and North America use ACEI 3 to 5 times more commonly than ARB, while Choi, et al.

14 reported that ARB use was higher than ACEI use at discharge in the Korean registry (39.4% vs. 17.9%, respectively). In the present study, the rate of ACEI use over 1 year (24.6%) was considerably lower than that of ARB (63.4%). There was a certain discrepancy between western countries and Korea in the drug use pattern of ACEI/ARB. ACEIs have a proven survival benefit for HF patients; however, the higher rate of dry cough in South Korean patients has led to greater utilization of ARBs.

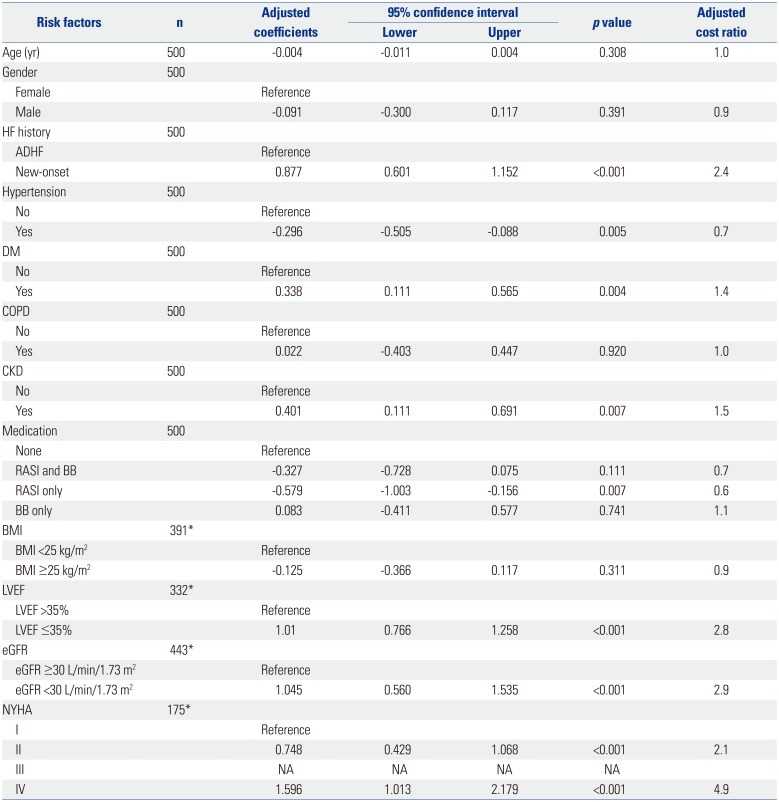

Several risk factors for higher costs were identified. First, we found that moderate to severe renal dysfunction, such as an eGFR <30 L/min/1.73 m

2, increased total HF-related healthcare expenditures. Renal dysfunction is common in patients with HF.

15 McAlister, et al.

16 and Cleland, et al.

17 reported that renal insufficiency is associated with poorer outcomes in patients with HF. An eGFR <30 L/min/1.73 m

2 at baseline was significantly associated with increased total costs (CR, 2.9;

p<0.001) and a 1-year per capita healthcare cost approximately 2 times higher than an eGFR >30 L/min/1.73 m

2. Moreover, our results demonstrated that the presence of CKD in patients with HF also contributes to high costs (CR, 1.5;

p=0.007). Since the average age of our population was 66.1 years and age is a major risk factor for CKD, careful monitoring for CKD is recommended for patients with HF.

18 Second, 57.6% of

de novo HF patients in our population experienced at least one hospitalization, compared to 16.6% of prevalent patients, which led to greater personal spending and more frequent use of healthcare resources. Smith, et al.

19 suggested that the difference in cost pattern between

de novo and acute decompensated HF (ADHF) patients would likely result from differences in clinical profiles. Metra, et al.

20 reported that patients with

de novo AHF are more likely to experience cardiology shock, have pulmonary edema, be hypertensive on admission, or have acute coronary syndrome. Patients with ADHF more frequently present with a history of myocardial infarction and medical comorbidities, such as DM, CKD, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Once an acute cardiac event results in pathological remodeling, a patient enters a repeated clinically stable and unstable situation. The results of this process are increased healthcare spending in patients with HF, particularly re-hospitalization.

21 Therefore, American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines emphasize intensive treatment for the early phase of HF. Third, increased healthcare costs were associated with low LVEF in patients with HF. According to the Korean CHF guideline, the survival rates of patients with HF reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) are likely to be lower or similar to that of patients with HF preserved ejection fraction.

22 Several studies showed no difference in mortality rates between patients with systolic HF and those with diastolic HF, although they included relatively small sample sizes. Meanwhile, the Cardiovascular Health study found that patients with HFrEF had lower survival rates than patients with a normal EF.

2324 Fourth, findings from our study suggest that the administration of RAS inhibitors may provide the additional benefit of lowered healthcare costs in patients with HF, whereas the administration of BB may not. Our multivariate analysis results are consistent with those of some recent reports. In a retrospective analysis of patients with HF or myocardial infarction discharged from the hospital, adherence and persistence of RAS inhibitors had a significant negative effect on total healthcare costs.

25 Obi, et al.

26 suggested that therapy with BB alone was associated with a higher risk of cost increases than RAS inhibitor monotherapy at 1–6 months before death in multivariate analyses. We ultimately observed higher costs and HF re-hospitalization rates during the post-index period in patients with I50.x diagnostic codes, compared to patients with I11 and I13 diagnostic codes. Several administration studies used only I50 codes to define HF, while some studies defined HF using I50, as well as I11, I13, and I42 as extended HF codes. We defined HF using I50, I11.0, I13.0, and I13.2 because cardiomyopathy (I42) is the main disease in many cases of HF. The mean total cost in patients with a diagnostic code of I50.x was higher than the mean total costs of other patients. In general, patients with pure HF codes (I50.x) have relatively severe symptoms and signs, compared to patients with hypertensive heart disease and HF. In our analysis, patients with hypertension had lower costs than those who did not. We included approximately 25% of patients with extended HF codes, which may have underestimated the overall burden of HF.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our study's results. There are inherent limitations associated with any retrospective data collection based on medical chart review. The association between total healthcare costs and risk factors is subject to bias, because some potential confounding factors that were not collected in our study might have affected the results of these analyses, and selection bias can occur in retrospective cohort studies. The study population was collected from tertiary referral hospitals and one general hospital, all of which are affiliated with universities and had a cardiovascular center comprised of specialists for HF. Also, the 500 samples may likely have had more severe disease than that for the entire population, since we focused on patient identified by exact HF diagnosis. For this reason, we used few exclusion criteria to maximize the external validity of generalization to all patient populations. Stratifying patients based on hospitalization experience and subgroup analyses allowed more flexibility in the interpretation of the results, but it remains possible that total healthcare costs per patient per year may have been underestimated due to the low proportion of hospitalized patients and those who died in the post-index period.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess healthcare costs for patients with acute hospitalized and CHF in South Korea. Our research builds on a larger body of empirical research concerning HF-related costs and will lead to additional studies that provide stronger evidence. We found that the majority of healthcare costs were related to hospitalization, especially those via ED admissions. Appropriate treatment strategies to prevent or decrease hospitalization are needed to reduce the economic burden on HF patients, and comorbid conditions and risk factors may be important targets for disease management efforts.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download