Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the efficacy and safety of naftopidil for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) patients, mainly focusing on changes in blood pressure (BP).

Materials and Methods

Of a total of 118 patients, 90 normotensive (NT) and 28 hypertensive (HT) patients were randomly assigned to be treated with naftopidil 50 mg or 75 mg for 12 weeks, once-daily. Safety and efficacy were assessed by analyzing changes from baseline in systolic/diastolic BP and total International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) at 4 and 12 weeks. Adverse events (AEs), obstructive/irritative subscores, quality of life (QoL) score, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), and benefit, satisfaction with treatment, and willingness to continue treatment (BSW) questionnaire were also analyzed.

Results

Naftopidil treatment decreased mean systolic BP by 18.7 mm Hg for the HT 50 mg group (p<0.001) and by 18.3 mm Hg for the HT 75 mg group (p<0.001) and mean diastolic BP by 17.5 mm Hg for the HT 50 mg group (p<0.001) and by 14.7 mm Hg for the HT 75 mg group (p=0.022). In the NT groups (both naftopidil 50 mg and 75 mg), naftopidil elicited no significant changes in BP from baseline values. After 12 weeks, naftopidil 50 and 75 mg groups showed significant improvements in IPSS scores (total, obstructive/irritative subscores, QoL score) and Qmax from baseline. AEs were reported in 7.8% (50 mg group) and 2.9% (75 mg group) of patients. In both the 50 mg and 75 mg groups, >86% of all patients agreed to continue their current medications.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the most common urological disorder in older men, and its incidence is expected to rise with increasing life expectancy. Hypertension is also a common disease in older age adults. Studies suggest that age-related increases in sympathetic noradrenergic activity may be a common pathophysiologic component in BPH and hypertension.1234 Even disregarding the possibility of a common pathology, it is estimated that at least one in four men aged >60 years could have concomitant BPH and hypertension.45

Selective α1-adrenoceptor (AR) antagonists are well known to be an effective, non-invasive treatment option for patients with BPH. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) can be improved by reduction of urethral pressure and prostatic smooth muscle tone by blocking the motor sympathetic adrenergic nerve supply to the prostrate. These agents are currently considered as first-line medical therapy for BPH patients,567 and numerous studies regarding their efficacy and tolerability have been reported.

Of these agents, naftopidil is an α1-AR antagonist that has high selectivity for the α1D subtype, showing 3- and 17-fold higher affinity for this subtype than for α1A and α1B subtypes, respectively.89 Although several clinical trials 9101112 demonstrating the efficacy of this drug for BPH patients have been reported, there are few reports of the cardiovascular responses associated with this drug during BPH treatment. Here, we aimed to determine the efficacy and safety of naftopidil for BPH/LUTS patients, focusing on 1) changes in blood pressure (BP) and 2) patient satisfaction and compliance.

This study was designed as a prospective, open-label study to determine the efficacy and safety of naftopidil (Flivas, Dong-A Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) at a single center (Yonsei University Health System, Severance Hospital, Seoul, Korea). The study protocol was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB approval No. 4-2014-0503, Yonsei University Health System). Patients provided written consent to participate in the study after having received an explanation of the protocol, including awareness of possible side effects.

Based on an assumption of a mean improvement in total international prostate symptom score (IPSS) from baseline of 3.0, a standard deviation of 5.3, and the assumption that 20% of patients will not be valid for inclusion in the per-protocol population, a sample size of at least 120 patients was required to obtain a power of 90%, with type 1 error of 0.05 (for a two-sided test). Results are reported for the intention to treat (ITT) population (all patients with a baseline BP and IPSS assessment and at least one valid post-baseline BP and IPSS assessment).

The enrolled patients suffered from LUTS and were considered fit for α1-AR antagonist treatment based on the decision of our physician. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were assigned into the normotensive (NT) group (defined as diastolic BP <90 mm Hg in a sitting position) or hypertensive (HT) group (diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg in a sitting position) and then randomly assigned by computer-generated random numbers into the naftopidil 50 mg group or 75 mg group for 12-week, oncedaily treatment.

BP was measured according to previous published guidelines:1314 1) patients were seated quietly for at least 5 minutes in a chair with their feet on the floor and arms at the level of the heart, 2) at least two measurements at 1–2 minute intervals were made, 3) we used a standard bladder (12–13×35 cm), a larger one for big arms, and 4) we deflated the cuff slowly (2 mm Hg/sec). Patient visits occurred at study entry and after 4 weeks and 12 weeks of treatment. Adverse events (AEs) were defined as symptoms that required discontinuation or change of the current medication.

The inclusion criteria included male ambulatory patients over 50 years of age with LUTS (total IPSS greater than 8). Patients with the following conditions were excluded: allergic drug reaction to α1-AR antagonists, orthostatic hypotension, a history of prostate-related surgery (open or endoscopic), suspicious prostate malignant condition on digital rectal examination and/or prostate-specific antigen (PSA) >10 ng/mL, a history of recurrent urinary tract infection or bladder stones, renal impairment (creatinine clearance rate <30 mL/min), severe hepatic disorders, the use of anticholinergic or cholinergic agents, the use of other α1-AR antagonists (tamsulosin, silodosin, alfuzosin, doxazocin, terazocin) within the previous 4 weeks, or the use of 5-reductase inhibitors or antiandrogens within the previous 3 months. Patients who were currently receiving or were planning to take any α-receptor agonists or β-receptor antagonists were also excluded.

The primary end-point of this study was to determine the safety and efficacy of naftopidil 50 and 75 mg treatment. This measure was assessed by analyzing changes from baseline in systolic/diastolic BP and total IPSS at 4 and 12 weeks. Secondary aims were to analyze 1) AEs; 2) improvement in IPSS obstructive/irritative subscores, IPSS quality of life (QoL) score, and maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax); and 3) benefit, satisfaction with treatment, and willingness to continue treatment (BSW) questionnaire with naftopidil 50 and 75 mg treatment at 4 and 12 weeks. The safety population was all patients who were randomized and who received at least one dose of study medication.

The two-sample t-test and Wilcoxon rank sum test were conducted to analyze continuous variables, and the chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables. Comparison of the efficacy variables was performed using an RM-ANOVA model with baseline values of the response variable as covariates for absolute change in IPSS from baseline. For efficacy evaluations, the last observation carried forward was applied to analyze the ITT population. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism software (version 5.00; GraphPad Instat, San Diego, CA, USA). Results were considered significant at p<0.05.

A total of 120 patients were screened and 118 were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Of these, 90 NT patients and 28 HT patients were randomized to receive naftopidil 50 mg or naftopidil 75 mg (group 1, NT 50 mg naftopidil; group 2, NT 75 mg naftopidil; group 3, HT 50 mg naftopidil, group 4, HT 75 mg naftopidil). In the NT group, 83 patients completed the study. The main reason for study discontinuation was AEs (6 patients, 6.6%), and one patient withdrew informed consent. In the HT group, 27 patients completed the study, and one discontinued because of loss during follow-up.

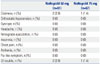

Baseline demographics and characteristics for all patients in the ITT population are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the four treatment groups in regards to age, height, weight, prostate volume, level of PSA, total IPSS scores, IPSS obstructive or irritative subscore, QoL due to urinary symptoms, Qmax, or post-void residual urine volume. Systolic and diastolic BP were significantly different between groups 1 and 2 and groups 3 and 4 (p<0.001).

Naftopidil treatment decreased the mean systolic BP by 18.7 mm Hg for group 3 (p<0.001) and by 18.3 mm Hg for group 4 (p<0.001) and the mean diastolic BP by 17.5 mm Hg for group 3 (p<0.001) and by 14.7 mm Hg for group 4 (p=0.022) (Fig. 2). However, in the NT groups (both naftopidil 50 and 75 mg), naftopidil caused no significant changes in BP from baseline values. After adjusting for age, significant changes in mean systolic and diastolic BPs from baseline values were found in group 3 and group 4 vs. group 1 and group 2 (Fig. 2).

The efficacy of naftopidil 50 and 75 mg on LUTS is summarized in Fig. 3. After 12 weeks of treatment, both groups showed significant improvements from baseline in total IPSS score (p<0.001). For both obstructive and irritative subscores, there were significant improvements from baseline to the final visit for both 50 and 75 mg doses (p<0.001 and p=0.028, respectively). Also, IPSS QoL scores after treatment with both drug doses improved significantly at 12 weeks (p<0.001). Both groups showed significant improvement in Qmax from baseline at 12 weeks (p=0.034 in naftopidil 50 mg group and p<0.001 in 75 mg group).

AEs were reported in four of 51 patients (7.8%) receiving naftopidil 50 mg and in two of 67 (2.9%) receiving naftopidil 75 mg (Table 2). No syncope was reported for either group. None of the patients reported retrograde ejaculation. Most AEs were mild or moderate in severity.

After completion of 12 weeks of treatment with naftopidil, satisfaction and compliance with this drug were assessed using the BSW questionnaire (Table 3). In both the 50 and 75 mg group, >76.6% of all patients felt they benefited from the treatment and were satisfied therewith. Moreover, 95.7% of patients in the naftopidil 50 mg group and 86% in the 75 mg group agreed to continue their current medications. The reasons for discontinuation were gastrointestinal trouble (n=2 in naftopidil 50 mg group and n=5 in 75 mg group) and dizziness (n=4 in naftopidil 75 mg group).

Considering the high incidence of patients with concomitant BPH and hypertension, physicians are concerned about the influence of BP changes during α1-AR antagonist treatment in such cases. Many studies regarding BP change in patients with BPH/hypertension treated with α1-AR antagonist have been reported. In 1995, Kirby15 reported that 12 weeks of treatment with doxazosin resulted in significant reductions in BP in HT patients, whereas minimal reductions were found in placebo-treated patients. Kaplan, et al.16 showed that doxazosin treatment did not cause a clinically significant BP change in NT patients. Chung and Hong5 reported that doxazosin gastrointestinal therapeutic system (GITS) treatment for 1 year resulted in a significantly greater reduction in BP in HT patients, compared with NT patients. Lee, et al.3 compared the BP-lowering effect of α1-AR antagonists in patients with or without concomitant antihypertensive drug treatment and reported that doxazosin GITS treatment resulted in optimal management of BP within the normal range, especially in baseline HT BP patients, irrespective of concomitant antihypertensive medication. Fawzy, et al.4 demonstrated that doxazosin is especially beneficial in the treatment of concomitant BPH and hypertension. Considering that older men might already be taking multiple medications for other diseases, the use of a single drug for two diseases might be valuable.

The majority of these reports, however, concern doxazosin treatment. Because doxazosin is a non-uroselective α1-AR antagonist, its influence on BP might be understandable. However, there are few reports on BP change with naftopidil, an α1-AR antagonist that has a high affinity for the α1D subtype. In our institution, we experienced stabilization of BP during naftopidil treatment for BPH/LUTS. From our experience, we think that this additional benefit of BPH medication results in increased satisfaction and compliance of the patients with this drug. Therefore, we aimed to further investigate the influence of naftopidil, mainly focusing on the cardiovascular aspects (i.e., BP change), as well as its efficacy for LUTS and patient satisfaction/compliance.

In terms of BP change with uroselective α1-AR antagonist in HT patients, a previous report3 showed that treatment with tamsulosin and alfuzosin resulted in only a slight reduction in systolic BP. However, in the present study, treatment with naftopidil 50 mg or 75 mg resulted in significant reductions in systolic and diastolic BP in baseline HT patients (Fig. 2). In NT patients, systolic and diastolic BP were optimally managed with naftopidil.

The pharmacological mechanism of the BP-lowering effect associated with naftopidil could be related to calcium-channel-blocking activity. In 1991, Himmel, et al.17 reported that naftopidil could act as a weak ligand for L-type calcium channels, leading to ca2+ antagonistic effects. Similarly, several reports1819 demonstrated that naftopidil has both α-AR and calcium-blocking activity. We think further studies are needed to address this.

In the present study, results from the BSW questionnaire suggested that treatment with naftopidil also shows increased satisfaction and compliance with this drug among patients. In both the 50 and 75 mg groups, the majority of patients felt benefit with satisfaction and agreed to continue this drug (Table 3).

Analysis of the BP-lowering effect of naftopidil with or without concomitant antihypertensive medication revealed significant reductions in systolic and diastolic BP in baseline HT patients, irrespective of concomitant antihypertensive medication (data not shown). These results are consistent with the previous report by Lee, et al.3 Regarding efficacy, the overall efficacy of BPH treatment with naftopidil for 12 weeks in the present study was similar to the results of a previous study.9 When comparing naftopidil 50 mg vs. 75 mg groups, overall efficacy parameters were superior with the higher dose (75 mg), although the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 3). In addition, several studies 1020212223 on naftopidil treatment reported improvement of irritative symptoms with this drug. Nishino, et al.10 reported that naftopidil was better than tamsulosin for nocturia. Other series 242526 suggested that upregulation of α1D-AR in the bladder contributes to the storage symptoms observed in bladder outlet obstruction and that targeting the α1D-AR with naftopidil may provide a new therapeutic approach for controlling storage symptoms in patients with BPH. However, in our study, we noted little difference in improvement in storage symptoms, compared with other α1-AR antagonists.

There are several limitation in our study. First, the study included a relatively small number of patients and a short period of follow-up. Second, we measured BP only with the patient in the seated position. We acknowledge the methodological flaw of not measuring BP in a supine position, in addition to the sitting position, to rule out any orthostatic hypotension that might be present. Finally, we were unable to determine why the naftopidil treatment lowered BP in HT patients, compared with NT patients, and future studies to elucidate the underlying mechanism will be needed. However, we think that our results provide adequate preliminary data to support the additional benefit (optimal management of BP within the normal range) of naftopidil treatment in BPH/LUTS patients.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Patient disposition. A total of 120 patients were screened and 118 were enrolled in this study. Ninety normotensive (NT) patients and 28 hypertensive (HT) patients were randomly assigned into the naftopidil 50 mg or naftopidil 75 mg group for 12-week, once-daily treatment. In the NT group, 83 patients completed the study. The main reason for study discontinuation was AEs (6 patients, 6.6%). In the HT group, 27 patients completed the study, and one discontinued because of loss during follow-up. AE, adverse event. |

| Fig. 2Comparison of the mean changes in BP from baseline value according to group. BP, blood pressure. |

| Fig. 3Change in efficacy parameters from baseline to each visit in the ITT population. IPSS, international prostate symptom score; SD, standard deviation; QoL, quality of life; Qmax, maximum urinary flow rate; ITT, intention to treat. |

Table 1

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

Table 2

Summary of Adverse Events*

Table 3

Results of the BSW Questionnaire

References

1. Boyle P, Napalkov P. The epidemiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia and observations on concomitant hypertension. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1995; 168:7–12.

2. Parsons JK. Modifiable risk factors for benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms: new approaches to old problems. J Urol. 2007; 178:395–401.

3. Lee SH, Park KK, Mah SY, Chung BH. Effects of α-blocker ‘add on’ treatment on blood pressure in symptomatic BPH with or without concomitant hypertension. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2010; 13:333–337.

4. Fawzy A, Hendry A, Cook E, Gonzalez F. Long-term (4 year) efficacy and tolerability of doxazosin for the treatment of concurrent benign prostatic hyperplasia and hypertension. Int J Urol. 1999; 6:346–354.

5. Chung BH, Hong SJ. Long-term follow-up study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the doxazosin gastrointestinal therapeutic system in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia with or without concomitant hypertension. BJU Int. 2006; 97:90–95.

6. McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, Andriole GL Jr, Dixon CM, Kusek JW, et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349:2387–2398.

7. Kirby RS, Roehrborn C, Boyle P, Bartsch G, Jardin A, Cary MM, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of doxazosin and finasteride, alone or in combination, in treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: the Prospective European Doxazosin and Combination Therapy (PREDICT) trial. Urology. 2003; 61:119–126.

8. Takei R, Ikegaki I, Shibata K, Tsujimoto G, Asano T. Naftopidil, a novel alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonist, displays selective inhibition of canine prostatic pressure and high affinity binding to cloned human alpha1-adrenoceptors. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1999; 79:447–454.

9. Gotoh M, Kamihira O, Kinukawa T, Ono Y, Ohshima S, Origasa H. Tokai Urological Clinical Trial Group. Comparison of tamsulosin and naftopidil for efficacy and safety in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int. 2005; 96:581–586.

10. Nishino Y, Masue T, Miwa K, Takahashi Y, Ishihara S, Deguchi T. Comparison of two alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists, naftopidil and tamsulosin hydrochloride, in the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized crossover study. BJU Int. 2006; 97:747–751.

11. Perumal C, Chowdhury PS, Ananthakrishnan N, Nayak P, Gurumurthy S. A comparison of the efficacy of naftopidil and tamsulosin hydrochloride in medical treatment of benign prostatic enlargement. Urol Ann. 2015; 7:74–78.

12. Komiya A, Suzuki H, Awa Y, Egoshi K, Onishi T, Nakatsu H, et al. Clinical effect of naftopidil on the quality of life of patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia: a prospective study. Int J Urol. 2010; 17:555–562.

13. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003; 42:1206–1252.

14. Cifkova R, Erdine S, Fagard R, Farsang C, Heagerty AM, Kiowski W, et al. Practice guidelines for primary care physicians: 2003 ESH/ESC hypertension guidelines. J Hypertens. 2003; 21:1779–1786.

15. Kirby RS. Doxazosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia: effects on blood pressure and urinary flow in normotensive and hypertensive men. Urology. 1995; 46:182–186.

16. Kaplan SA, Meade-D'Alisera P, Quiñones S, Soldo KA. Doxazosin in physiologically and pharmacologically normotensive men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1995; 46:512–517.

17. Himmel HM, Glossmann H, Ravens U. Naftopidil, a new alpha-adrenoceptor blocking agent with calcium antagonistic properties: characterization of Ca2+ antagonistic effects. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1991; 17:213–221.

18. Sponer G, Borbe HO, Müller-Beckmann B, Freud P, Jakob B. Naftopidil, a new adrenoceptor blocking agent with Ca(2+)-antagonistic properties: interaction with adrenoceptors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992; 20:1006–1013.

19. Grundke M, Himmel HM, Wettwer E, Borbe HO, Ravens U. Characterization of Ca(2+)-antagonistic effects of three metabolites of the new antihypertensive agent naftopidil, (naphthyl)hydroxy-naftopidil, (phenyl)hydroxy-naftopidil, and O-desmethyl-naftopidil. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1991; 18:918–925.

20. Sugaya K, Nishijima S, Miyazato M, Ashitomi K, Hatano T, Ogawa Y. Effects of intrathecal injection of tamsulosin and naftopidil, alpha-1A and -1D adrenergic receptor antagonists, on bladder activity in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002; 328:74–76.

21. Utsunomiya N, Matsumoto K, Tsunemori H, Muguruma K, Kawakita M, Kamiyama Y, et al. [A crossover comparison study on lower urinary tract symptoms with overactive bladder secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia: naftopidil versus tamsulosin with solifenacin]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2016; 62:341–347.

22. Sakai H, Igawa T, Onita T, Furukawa M, Hakariya T, Hayashi M, et al. [Efficacy of naftopidil in patients with overactive bladder associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: prospective randomized controlled study to compare differences in efficacy between morning and evening medication]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2011; 57:7–13.

23. Oh-oka H. Effect of naftopidil on nocturia after failure of tamsulosin. Urology. 2008; 72:1051–1055.

24. Hampel C, Dolber PC, Smith MP, Savic SL, Th roff JW, Thor KB, et al. Modulation of bladder alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtype expression by bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2002; 167:1513–1521.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download