This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Purpose

Our research was designed to test and explore the relationships among embitterment, social support, and perceptions of meaning in life in the Danwon High School survivors of the Sewol ferry disaster.

Materials and Methods

Seventy-five Sewol ferry disaster survivors were eligible for participation, and were invited to participate in the study 28 months after the disaster. Forty-eight (64%) survivors (24 males, 24 females) completed questionnaires; the Posttraumatic Embitterment Disorder (PTED) scale, the Functional Social Support Questionnaire (FSSQ), and the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ).

Results

PTED scores were negatively correlated with scores on the FSSQ and the Presence of Meaning (MLQ-P) (r=-0.43 and -0.40, respectively). The hierarchical regression analysis showed that FSSQ scores may fully mediate the effects of PTED scores on MLQ-P scores, given that the indirect effect was significant whereas the direct effect was not (95% confidence interval=-0.5912 to -0.0365).

Conclusion

These findings imply that therapies targeting embitterment may play a vital role in increasing positive cognitions, such as those related to perceived social support and the meaningfulness of life.

Go to :

Keywords: Sewol ferry disaster, Danwon High School survivors, posttraumatic embitterment, meaning in life, social support

INTRODUCTION

On April 16, 2014, the Sewol ferry sank in the West Sea off the coast of South Korea. Only 181 of the 476 passengers survived. Among these survivors was a group of students from Danwon High School who were on a school trip at the time of the accident; 75 of these individuals, who came to be known as the “Danwon High School survivors,” survived, whereas 250 died or were never found. The school's vice principal, who had been rescued from the ferry, committed suicide a few days after the disaster,

1 and a female Danwon High School survivor tried to kill herself by overdosing on medication and was hospitalized in a state of unconsciousness.

2 This student had written a letter explaining that she missed her friend, who had died in the disaster.

An inability to find meaning in life and a general lack of a sense of self-efficacy have been identified as significant predictors of depressive symptomatology after combat trauma.

3 Significant correlations have also been observed among one dimension of meaning (the search for meaning), perceived social support, and posttraumatic growth in survivors of the Colorado floods.

4 A limited sense of meaning in life is associated with depression, hopelessness and suicide, as well as substance abuse and emotional dysregulation, whereas perceiving life to be meaningful is thought to facilitate optimal recovery from adverse events.

5

The Danwon High School survivors were disappointed in and resentful about the failure of the national disaster response, and they refer to their survival in terms of “escape” instead of “rescue.” Intrusive media attention increased this mistrust and resentment. Furthermore, distorted news reports led to malicious comments and cyberbullying, which elicited feelings of hurt and confusion.

6 One consequence of a negative life event, even if it is neither life-threatening and nor repeated, is embitterment, which can impair mental health.

Embitterment results from persistent experiences of being let down or insulted, feeling like a “loser,” or wishing for revenge but feeling helpless.

7 Embitterment has been observed in East Germans who experienced uncertainty or sudden, uncontrollable events, such as the abrupt and unexpected loss of a job during the unification of Germany.

7 Historically, embitterment is a familiar concept to Koreans, as the Korean culture-bound syndrome, Hwa-Byung (literally, fire disease), has been understood as deriving from anger.

8

It is important that survivors of traumatic events reduce feelings of embitterment and receive increased social support. One study of former political prisoners found that embitterment was correlated with overgeneral autobiographical memory, and that survivors with social support networks were better able to recall specific memories.

9

To the best of our knowledge, scant research has focused on the relationship among embitterment, social support, and the perception of meaning in life among survivors of disasters. However, as noted above, embitterment has been a common affective response to traumatic events among South Koreans, and the perception of meaning in life has been shown to enhance recovery from negative events. Our research, therefore, was designed to test and explore the relationships among embitterment, social support, and perceptions of meaning in life in the Danwon High School survivors of the Sewol ferry disaster. Specifically, we hypothesized that 1) embitterment, social support, and the perception of meaning in life are significantly correlated and 2) social support mediates the relationship between posttraumatic embitterment (PTE) and the perception of meaning in life.

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Procedure

Owing to the small number of eligible participants, we tried to include as many as of this cohort as possible rather than perform random or purposive sampling. Danwon High School established the Mental Health Center following the Sewol tragedy, and a school psychiatrist and psychologists have provided the students with regular mental health checkups and any necessary counseling. During their first summer vacation as university students (28 months after the Sewol ferry disaster), individuals who were already enrolled in the Disaster Cohort Study at the time of their graduation were invited to participate in the present study. The invitation was performed via telephone by the former school psychiatrist and psychologists, and all potential respondents had the opportunity to decline. The former school psychiatrist of Danwon High School met with the participants.

Participants

Seventy-five Sewol ferry disaster survivors were eligible for participation, and were invited to participate in the study 28 months after the disaster. Forty-eight (64%) survivors (24 males, 24 females) responded to the survey.

Variables and measures

Data on socioeconomic variables, including gender and birth year, were gathered, and participants also completed the Posttraumatic Embitterment Disorder (PTED) scale, the Functional Social Support Questionnaire (FSSQ), and the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ).

The PTED scale is a 19-item questionnaire designed to assess PTED symptoms. Respondents are asked to rate the extent which each item applies to them using the following five-point Likert scale: 0, not at all; 1, hardly; 2, partially; 3, very much; and 4, extremely. Higher scores reflect higher levels of PTE. A previous study reported the Cronbach's alpha of this questionnaire to be 0.93, indicating a high level of internal consistency. The Spearman rho correlation coefficient was 0.71 for the sum score, ranging between 0.53 and 0.86 for individual items and thus indicating adequate test-retest reliability.

10 The Korean version of the PTED scale is a reliable and valid measure of embitterment as an emotional reaction to a negative life event among Korean adults.

8

The FSSQ, a 14-item self-report questionnaire with excellent internal consistency (α=0.89) in Korean samples, was used to assess perceived social support.

11 The FSSQ asks participants to rate each item on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (much less than I would like) to 4 (as much as I would like). Total scores range from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support. A validation study demonstrated that this scale has a two-factor structure: confidant support or the ability to share important information, and affective support or emotional support.

12

The MLQ comprises two subscales that were developed to be relatively independent: the Presence of Meaning (MLQ-P) and the Search for Meaning (MLQ-S).

13 Participants are asked to rate their reponse to each of 10 statements according to the following options 1=absolutely untrue, 2=mostly untrue, 3=somewhat untrue, 4=can't say whether it's true or false, 5=somewhat true, 6=mostly true, and 7=absolutely true. In the original validation study conducted in American students, the scale exhibited good internal consistency and test-retest reliability, as well as structural, convergent, and discriminant validity, with Cronbach's alpha values ranging between 0.82 and 0.86, and 0.86 and 0.87, for the MLQ-P and MLQ-S, respectively.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Medical Center (IRB No. H-1505-054-002). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Statistical analysis

We first calculated descriptive statistics to examine the characteristics of participants (e.g., gender and year of birth). Second, we used bivariate correlation analyses to examine associations among scores on the PTED scale, FSSQ, and MLQ. Two mediation analyses used Baron and Kenny's

14 approach to examine whether social support (FSSQ) mediated the relationship between PTED scale scores and meaning in life (MLQ-P=Mode 1, MLQ-S=Model 2).

We also performed bootstrapping with PPOCESS MECRO

15 using SPSS software (ver. 20; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The bootstrapping method

16 was used to test the significance of the mediational paths using 1000 bootstrap samples and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Effects with

p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Go to :

RESULTS

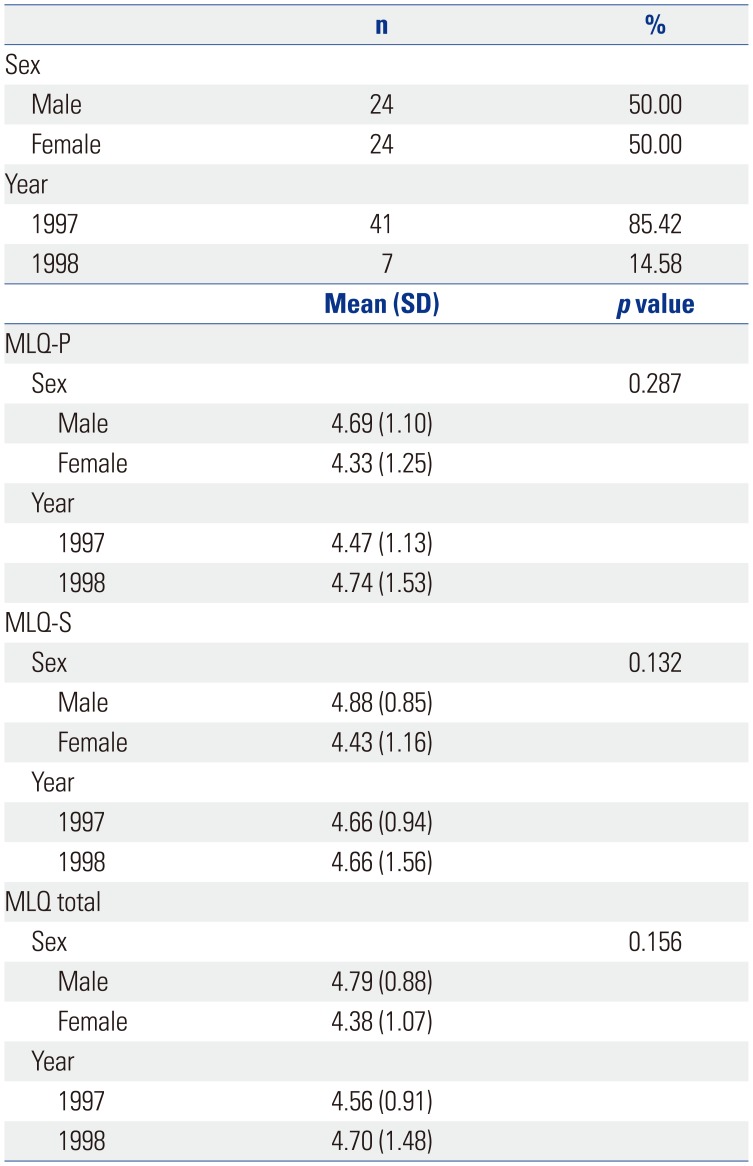

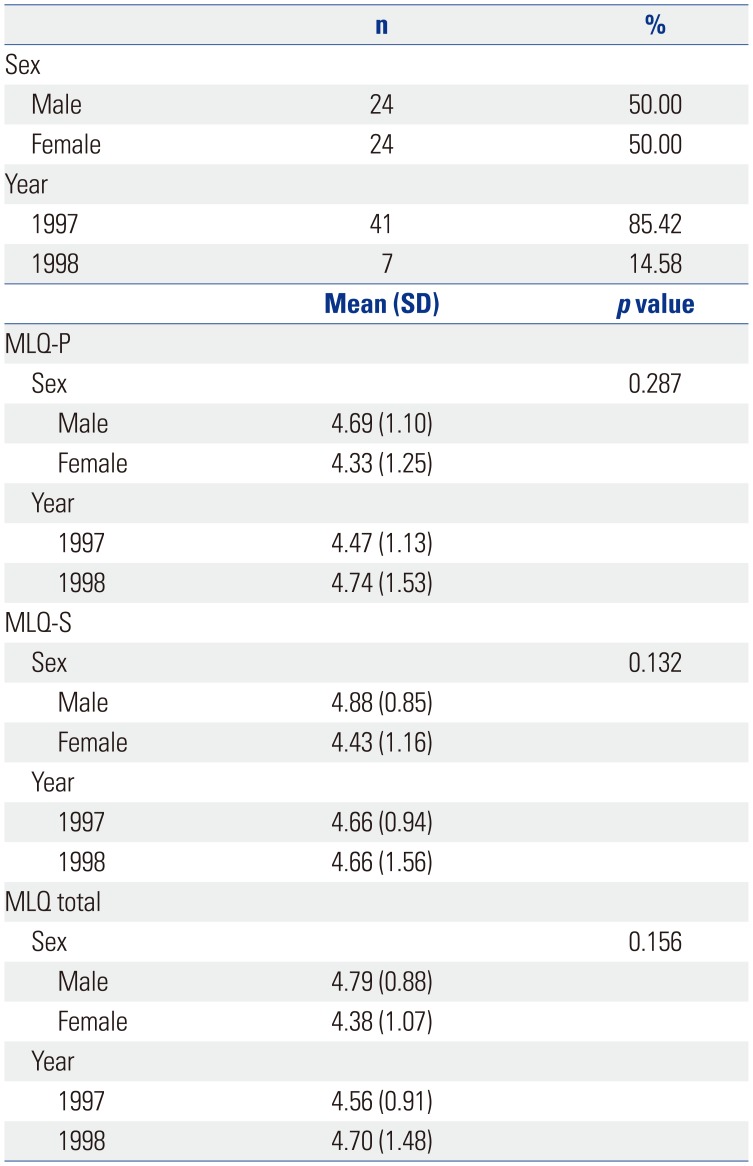

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants, and their MLQ scores according to demographic characteristics. Of the 48 participants included in our study, 24 were male and 24 were female. More than four-fifths (85.42%) were born in 1997. There were no significant differences in MLQ scores by demographic characteristics (

p>0.05).

Table 1

The Demographic Characteristics of the Participants and Their MLQ Scores According to Background Characteristics (n=48)

|

n |

% |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Male |

24 |

50.00 |

|

Female |

24 |

50.00 |

|

Year |

|

|

|

1997 |

41 |

85.42 |

|

1998 |

7 |

14.58 |

|

Mean (SD) |

p value |

|

MLQ-P |

|

|

|

Sex |

|

0.287 |

|

Male |

4.69 (1.10) |

|

|

Female |

4.33 (1.25) |

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

1997 |

4.47 (1.13) |

|

|

1998 |

4.74 (1.53) |

|

|

MLQ-S |

|

|

|

Sex |

|

0.132 |

|

Male |

4.88 (0.85) |

|

|

Female |

4.43 (1.16) |

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

1997 |

4.66 (0.94) |

|

|

1998 |

4.66 (1.56) |

|

|

MLQ total |

|

|

|

Sex |

|

0.156 |

|

Male |

4.79 (0.88) |

|

|

Female |

4.38 (1.07) |

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

1997 |

4.56 (0.91) |

|

|

1998 |

4.70 (1.48) |

|

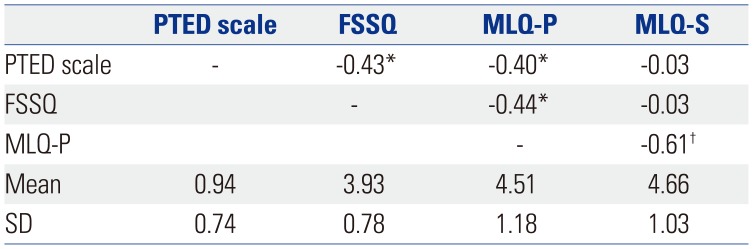

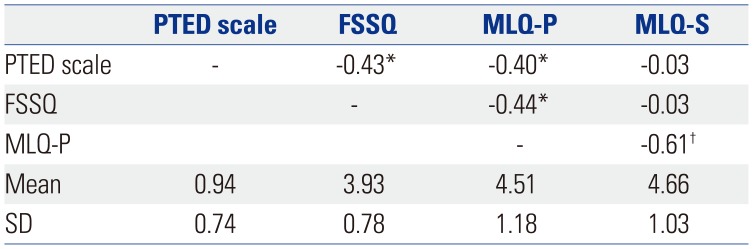

Table 2 shows the bivariate correlations among the variables of interest included in the hypothetical model. As expected, PTED scores were negatively correlated with scores on the FSSQ and MLQ-P (r=-0.43 and -0.40, respectively). However, PTED scores were not associated with scores on the MLQ-S (r=0.03,

p>0.05). On the other hand, FSSQ scores were significantly positively associated with MLQ-P, but not with MLQ-S scores (r=-0.44 and -0.03, respectively). Additionally, MLQ-P scores were significantly correlated with MLQ-S scores (r= 0.61,

p<0.001).

Table 2

The Bivariate Correlations among the Scores of PTED Scale, FSSQ, MLQ-P, and MLQ-S (n=48)

|

PTED scale |

FSSQ |

MLQ-P |

MLQ-S |

|

PTED scale |

- |

−0.43*

|

−0.40*

|

−0.03 |

|

FSSQ |

|

- |

−0.44*

|

−0.03 |

|

MLQ-P |

|

|

- |

−0.61†

|

|

Mean |

0.94 |

3.93 |

4.51 |

4.66 |

|

SD |

0.74 |

0.78 |

1.18 |

1.03 |

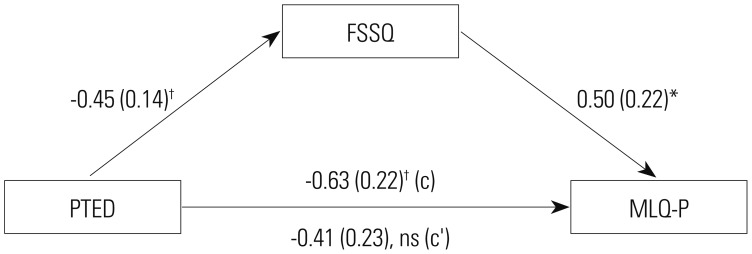

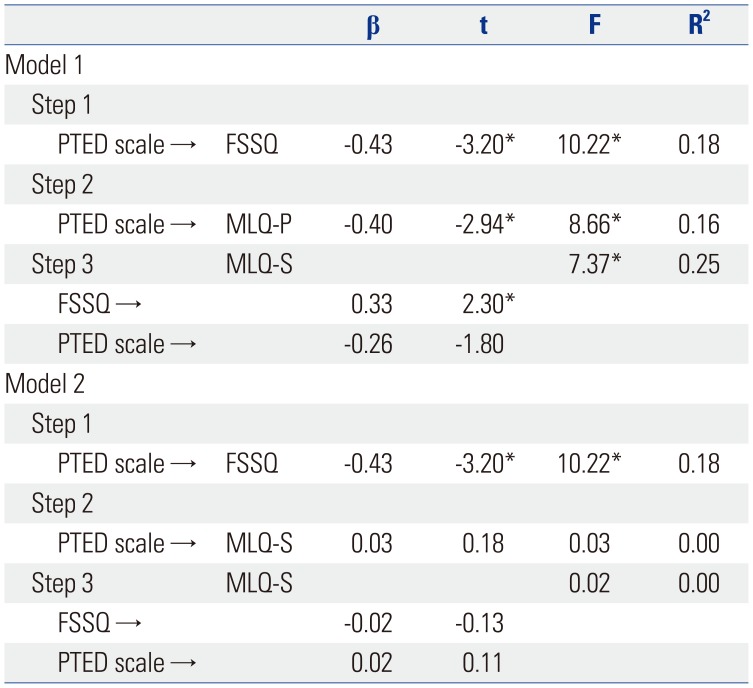

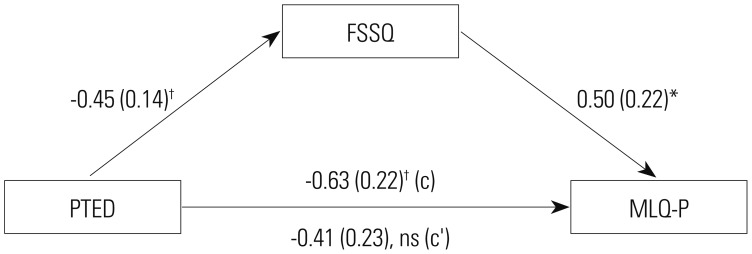

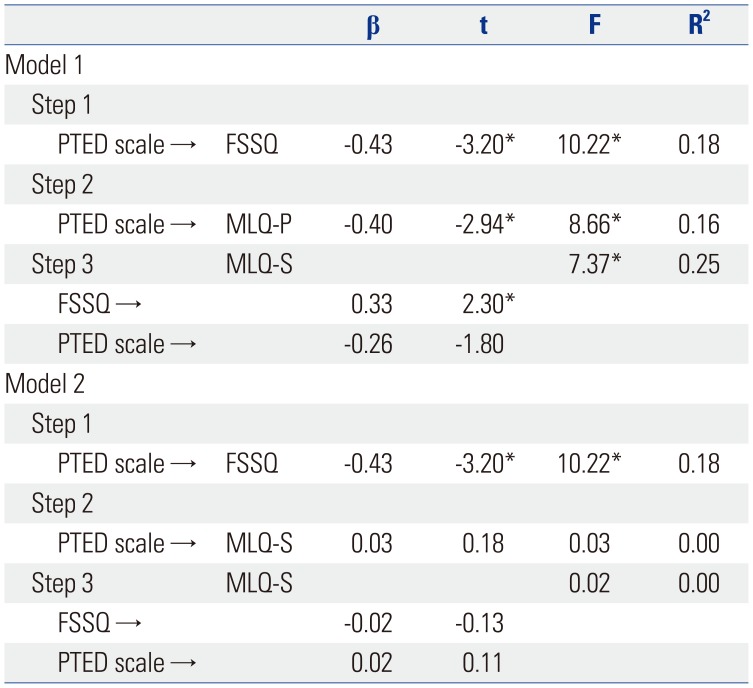

Table 3 presents the analyses of the models used to determine whether FSSQ scores mediated the significant relationship between PTED and MLQ-P scores. We conducted a three-step hierarchical regression analysis for two models. In the first step of model 1, PTED scores were significantly related to MLQ-P scores (B=-0.63, SE=0.22). In the second step, the linear regression analysis revealed that PTED scores were significantly related to FSSQ scores (B=-0.45, SE=0.14). In the third step, the multiple regression analysis indicated that FSSQ scores were significantly related to MLQ-P scores when PTED scores were held constant (B=0.50, SE=0.22); this step also revealed that PTED scores were not significantly related to MLQ-P scores when FSSQ scores were held constant (B=-0.41, SE=0.23). Additionally, analyses relying on the bootstrapping method revealed a significant indirect effect of PTED scores on MLQ-P scores via FSSQ scores when 1000 replications and a 95% CI were used (-0.5912:-0.0365). In summary, the hierarchical regression analysis showed that FSSQ scores may fully mediate the effects of PTED scores on MLQ-P scores, given that the indirect effect was significant whereas the direct effect was not (

Fig. 1). However, in model 2, PTED scores were not significantly related to MLQ-S scores. Accordingly, model 2 was not subjected to the subsequent steps because the total effect was not significant.

| Fig. 1Social support mediates the relationship between posttraumatic embitterment and presence of meaning in life. *p<0.050, †p<0.01. PTED, Posttraumatic Embitterment Disorder; FSSQ, Functional Social Support Questionnaire; MLQ, Meaning in Life Questionnaire; MLQ-P, Presence of Meaning; MLQ-S, Search for Meaning; c, total effect ; c', direct effect; ns, not significant.

|

Table 3

Results of Hierarchical Regression Models Exploring the Effect of PTED and FSSQ on MLQ-P and MLQ-S (n=48)

|

|

β |

t |

F |

R2

|

|

Model 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Step 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PTED scale → |

FSSQ |

−0.43 |

−3.20*

|

10.22*

|

0.18 |

|

Step 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PTED scale → |

MLQ-P |

−0.40 |

−2.94*

|

8.66*

|

0.16 |

|

Step 3 |

MLQ-S |

|

|

7.37*

|

0.25 |

|

FSSQ → |

|

0.33 |

2.30*

|

|

|

|

PTED scale → |

|

−0.26 |

−1.80 |

|

|

|

Model 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Step 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PTED scale → |

FSSQ |

−0.43 |

−3.20*

|

10.22*

|

0.18 |

|

Step 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PTED scale → |

MLQ-S |

0.03 |

0.18 |

0.03 |

0.00 |

|

Step 3 |

MLQ-S |

|

|

0.02 |

0.00 |

|

FSSQ → |

|

−0.02 |

−0.13 |

|

|

|

PTED scale → |

|

0.02 |

0.11 |

|

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that PTE was negatively correlated with the perception of meaning in life among Danwon High School survivors. However, the level of PTE was not significantly related to searching for meaning in life. The “presence of meaning in life” refers to the extent to which people comprehend, make sense of, or perceive significance in their lives, as well as the degree to which they view themselves as having a purpose or mission.

13 The “search for meaning in life” refers to their motivation to find goals and a purpose in life. Our results indicate that, although embitterment might have temporarily interfered with the ability of Danwon High School survivors to perceive meaning in life, it did not prevent them from searching for life goals that would eventually imbue their lives with meaning.

Consistent with previous research, embitterment was negatively correlated with perceived social support. A cross-sectional study on chronic embitterment among occupational health professionals showed that embittered staff perceived their organization as being unsupportive and characterized by low levels of procedural justice.

17 People who are embittered typically feel victimized, experience resentment and injustice, resist help, and have difficulty coping.

18 Decreasing embitterment encourages positive beliefs, assists survivors in perceiving others as being supportive, and promotes help-seeking.

In this research, hierarchical regression analysis showed that perceived social support may fully mediate the effect of PTE on the perception of meaning in life. Our findings imply that clinical interventions to reduce PTE may help disaster survivors find meaning in life by increasing their perceived level of social support. However, data on the treatment of embitterment remain inadequate. One pilot study reported significant and clinically meaningful reductions in Symptom Checklist scores after wisdom therapy compared to routine treatment, and suggested that cognitive-behavior therapy based on wisdom psychology might constitute a valid approach to treating PTED.

10 Further studies about the determinants of and treatments for embitterment are needed.

The present study had several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design renders it difficult to identify causal relationship among factors. As a result, a use of a longitudinal design is recommended. Second, sampling bias may have occurred, as only 64% of the surviving students participated in the study; therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Third, although the analysis accounted for demographic characteristics and psychological variables, some additional factors, such as quality of parental relationships, self-efficacy, and coping style, should be included in future studies. Fourth, although the MLQ underwent translation and back-translation by a native speaker, this scale has yet to be standardized for a Korean population.

In conclusion, despite these limitations, our study provides important insights into PTE and the perception of meaning in life. Our study analyzed the mediating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between PTE and the perception of meaning in life, and proposed a new approach to mental health interventions. Indeed, it is necessary to develop clinical interventions to reduce PTE by increasing perceived social support and resilience in response to emotional difficulties. Such interventions will reduce stress and increase the perception of life having meaning. Therefore, therapies aimed at reducing embitterment may play an important role in increasing perceived social support and, eventually, a sense of meaning in life.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Korean Mental Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HM15C1054).

Go to :

Notes

Go to :

References

3. Blackburn L, Owens GP. The effect of self efficacy and meaning in life on posttraumatic stress disorder and depression severity among veterans. J Clin Psychol. 2015; 71:219–228. PMID:

25270887.

4. Dursun P, Steger MF, Bentele C, Schulenberg SE. Meaning and posttraumatic growth among survivors of the september 2013 colorado floods. J Clin Psychol. 2016; 72:1247–1263. PMID:

27459242.

5. Marco JH, Pérez S, García-Alandete J, Moliner R. Meaning in life in people with borderline personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017; 24:162–170. PMID:

26639791.

6. Kim SS. Results of the studies on supports for the victims of the Sewol ferry disaster. Presentation on the results of the studies on supports for the victims of the Sewol ferry disaster. Seoul: Kim Koo Museum & Library;2016. 7. 20.

7. Linden M. Posttraumatic embitterment disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2003; 72:195–202. PMID:

12792124.

8. Shin C, Han C, Linden M, Chae JH, Ko YH, Kim YK, et al. Standardization of the Korean version of the posttraumatic embitterment disorder self-rating scale. Psychiatry Investig. 2012; 9:368–372.

9. Kleim B, Griffith JW, Gäbler I, Schützwohl M, Maercker A. The impact of imprisonment on overgeneral autobiographical memory in former political prisoners. J Trauma Stress. 2013; 26:626–630. PMID:

24114806.

10. Linden M, Baumann K, Lieberei B, Rotter M. The Post-Traumatic Embitterment Disorder Self-Rating Scale (PTED Scale). Clin Psychol Psychother. 2009; 16:139–147. PMID:

19229838.

11. Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988; 26:709–723. PMID:

3393031.

12. Suh SY, Im YS, Lee SH, Park MS, Yoo T. A study for the development of Korean version of the Duke-UNC functional social support questionnaire. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 1997; 18:250–260.

13. Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol. 2006; 53:80–93.

14. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986; 51:1173–1182. PMID:

3806354.

15. Hayes AF. PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. 2012. accessed on 2017 March 17. Available at:

http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

16. Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002; 7:422–445. PMID:

12530702.

17. Sensky T, Salimu R, Ballard J, Pereira D. Associations of chronic embitterment among NHS staff. Occup Med (Lond). 2015; 65:431–436. PMID:

26136596.

18. Blom D, Thomaes S, Bijlsma JW, Geenen R. Embitterment in patients with a rheumatic disease after a disability pension examination: occurrence and potential determinants. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014; 32:308–314. PMID:

24708914.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download