Abstract

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is a serious complication in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. The limiting volume of contrast medium is safest and most reliable strategy for CIN prevention. Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) serves as an attractive alternative imaging tool to angiography in many steps during PCI, thereby reducing the use of contrast agents. Here, we reported a case of successfully treated unprotected left main bifurcation lesion with heavily calcified and diffuse lesion under the IVUS-guided PCI using low volumes of contrast dye of total 12 cc in an elderly patient.

Contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) is a serious complication in patients undergoing coronary angiography and any intervention that require contrast injection. CIN is defined as absolute (> or=0.5 mg/dL) or relative increase (> or=25%) of serum creatinine after 48–72 hours of exposure to a contrast agent compared to baseline serum creatinine values, when alterative explanations for renal impairment have been excluded.1 Patients with complex coronary artery disease requiring longer procedural time and higher dosage of contrast media, increase the risk for development of CIN. Although the incidence of CIN following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was estimated to be between 0.6 to 2.3% in general population, it was reported to be 5.4–6.2% in patients undergoing PCI for lesions of chronic total occlusion and up to 20% in high risk patients.23 The use of low-dose contrast media is important for prevention of CIN. Herein, we report a case of successful treatment of unprotected left main (LM) bifurcation lesion with minimum contrast volume of 12 cc using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guidance in an elderly patient.

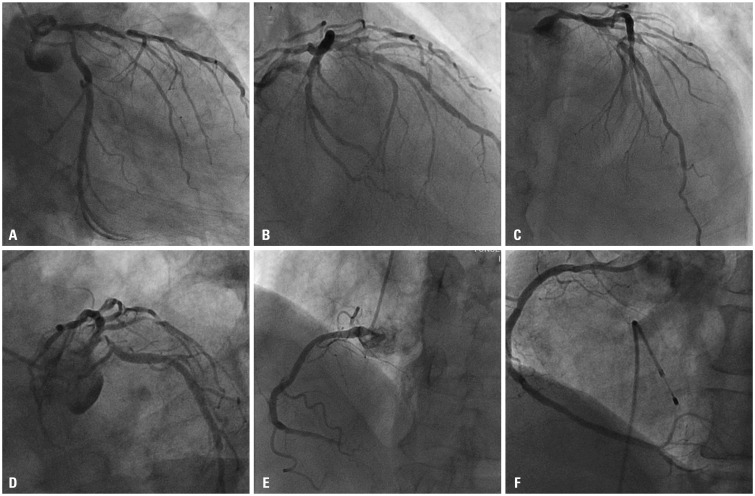

A 79-year-old male was referred due to significant coronary artery stenosis noted by coronary computed tomographic angiography (CTA). Coronary CTA showed 3-vessel coronary artery and LM disease involving bifurcation with long and heavily calcified lesions of high syntax score of 33. Laboratory investigation revealed normal renal function (serum creatinine 0.85 mg/dL). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed absence of regional wall motion abnormality and pharmacologic techneitum-99m myocardial single photon emission computed tomography revealed reversible defect in the inferior wall. To minimize the risk of CIN, intravenous normal saline infusion and usage of iso-osmolar iodine contrast was done. Initial coronary angiography revealed total occlusion of distal right coronary artery (RCA) and LM disease involving bifurcation (Fig. 1A-D). RCA lesion was successfully revascularized with 2.5×13 mm sized Orsiro (Biotronik, Berlin, Germany) stent implantation with total 100cc of contrast volume (Fig. 1E and F).

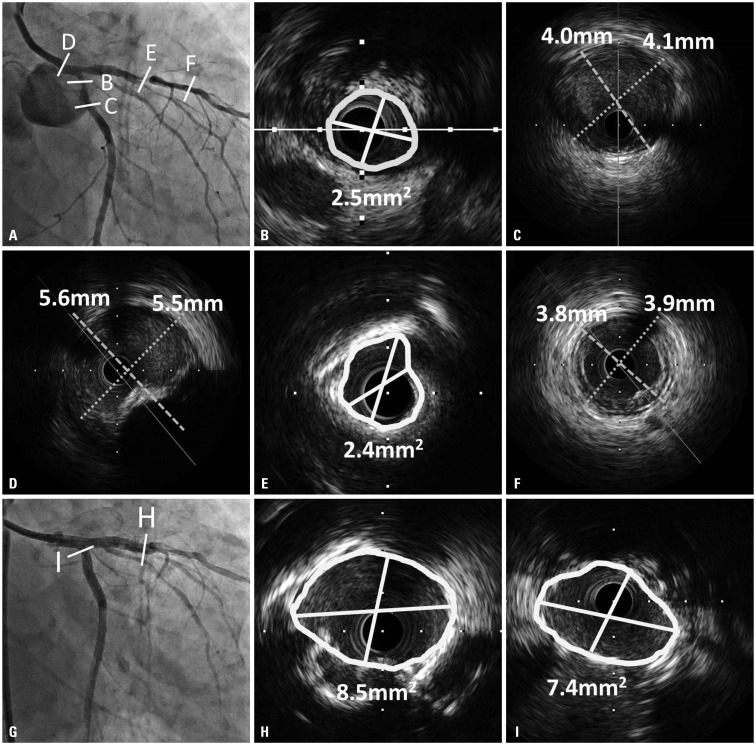

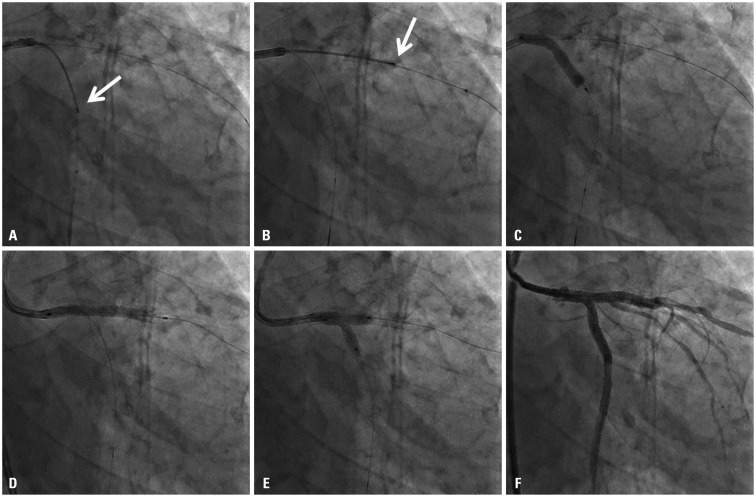

Staged PCI for treatment of LM bifurcation lesion was done via femoral access one week later. Initial left coronary angiography was done with 6 cc injection of contrast dye (Fig. 2A). Prior to PCI, initial angiogram which had already been performed one week ago with same angle of projection was uploaded to the monitor for PCI guidance. After advancing a guide wire into both left anterior descending (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCX) without use of contrast dye, pre-stent IVUS was performed to determine optimal proximal and distal stent landing zones, stent diameter and length (Fig. 2B-F). Recording of position of IVUS transducer on fluoroscopic image was useful to determine the distal landing zone of stent (Fig. 3A and B, arrow). Based on the angiographic and IVUS findings, two stent technique in a culotte fashion was performed with fluoroscopic guidance, but without the use of contrast dye. Both branches were pre-dilated with 3.5×15 mm non-complaint balloon. Then, a 3.5×23 mm XIENCE Alpine (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) stent was deployed at 11 atm in LM to LCX (Fig. 3C). The stent was re-crossed and the un-stented branch was dilated with 2.0×12 mm and 3.5×23 mm non-complaint balloons. The 3.5×38 mm XIENCE Alpine stent was positioned towards the LM to LAD at 14 atm (Fig. 3D). The first stent was re-crossed and final kissing balloon inflation was performed with two 3.5×15 mm non-compliant balloons (Fig. 3E). Post-stent IVUS confirmed optimal stent deployment without acute complications; minimal lumen area was 8.5 mm2 in proximal LAD and 7.4 mm2 in ostial LCX (Fig. 2G, H, and I). After confirmation of stent optimization with post-stent IVUS examination, final second angiography with 6 cc contrast injection revealed successful results (Fig. 3F). During the two stent technique in a culotte fashion for LM bifurcation lesions, successful results were achieved with minimal amount of contrast dye and only two angiographic imaging under the IVUS guidance. This patient was clinically stable for 2 days without CIN (Serum creatinine 0.74 mg/dL). This patient was discharged 2 days after PCI and has been uneventful.

Using small volumes of contrast dye (12 cc), a case of unprotected LM bifurcation lesion was successfully treated under the IVUS-guided PCI in an elderly patient without CIN, despite this patient had a higher chance to develop CIN during PCI because of old age, long and heavily calcified, LM bifurcation coronary lesion of high syntax score of 33, which usually requires larger amount of contrast medium compared to routine procedure.

Compared to patients without CIN, those with CIN are associated with higher in-hospital mortality (1.4% vs. 22%, respectively, p<0.001) and long term mortality (1-year mortality rate: 3.7% vs. 12.1%, respectively, p<0.001 and 5-year mortality rate: 14.5% vs. 44.6%, respectively, p<0.001).3 Therefore, prevention of CIN is the best strategy for improving short and long term outcome after PCI. Usage of minimum volume of contrast dye is safest and most reliable method.

There are several techniques and imaging modalities to minimize contrast volume including pre-interventional imaging to plan interventional procedure, extensive use of reference images of target vessel anatomy, extensive use of diluted contrast during PCI, use of IVUS or hybrid imaging.456 Especially, IVUS serves as an attractive alternative imaging tool to angiography during PCI. Previous study reported that IVUS guidance significantly reduces the dose of contrast compared with an angiography-only approach, that contrast volume used was 3-fold lower in IVUS-guided group compared with angiography-guided group, and that there were notably no differences in fluoroscopy time, the number of cine runs, or radiation dose.7 IVUS provided valuable information on cross-sectional coronary vascular structure, suitable landing zone, and assistance in selection of treatment strategy including stent diameter and length and acute complication.

We used minimal dosage of contrast at the end to confirm any injuries. We strongly believe that ultra-low contrast volume reduces the rate of CIN development in patients with chronic renal disease who undergo coronary angiography or PCI.68

In conclusion, IVUS guidance is a promising method for patients with renal insufficiency who need for inevitable PCI and may be useful to all patients with a high risk of CIN.

References

1. Mehran R, Nikolsky E. Contrast-induced nephropathy: definition, epidemiology, and patients at risk. Kidney Int Suppl. 2006; (100):S11–S15. PMID: 16612394.

2. Lin YS, Fang HY, Hussein H, Fang CY, Chen YL, Hsueh SK, et al. Predictors of contrast-induced nephropathy in chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention. 2014; 9:1173–1180. PMID: 24561734.

3. Rihal CS, Textor SC, Grill DE, Berger PB, Ting HH, Best PJ, et al. Incidence and prognostic importance of acute renal failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2002; 105:2259–2264. PMID: 12010907.

4. Azzalini L, Spagnoli V, Ly HQ. Contrast-induced nephropathy: from pathophysiology to preventive strategies. Can J Cardiol. 2016; 32:247–255. PMID: 26277092.

5. Nayak KR, Mehta HS, Price MJ, Russo RJ, Stinis CT, Moses JW, et al. A novel technique for ultra-low contrast administration during angiography or intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 75:1076–1083. PMID: 20146209.

6. Ali ZA, Karimi Galougahi K, Nazif T, Maehara A, Hardy MA, Cohen DJ, et al. Imaging- and physiology-guided percutaneous coronary intervention without contrast administration in advanced renal failure: a feasibility, safety, and outcome study. Eur Heart J. 2016; 37:3090–3095. PMID: 26957421.

7. Mariani J Jr, Guedes C, Soares P, Zalc S, Campos CM, Lopes AC, et al. Intravascular ultrasound guidance to minimize the use of iodine contrast in percutaneous coronary intervention: the MOZART (minimizing contrast utilization with IVUS guidance in coronary angioplasty) randomized controlled trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014; 7:1287–1293. PMID: 25326742.

8. Okumura N, Hayashi M, Imai E, Ishii H, Yoshikawa D, Yasuda Y, et al. Effects of carperitide on contrast-induced acute kidney injury with a minimum volume of contrast in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephron Extra. 2012; 2:303–310. PMID: 23341832.

Fig. 1

Initial angiography is shown. There were significant stenosis of left main coronary artery, proximal left anterior descending artery with heavy calcification and ostium to proximal left circumflex (A-D). Right coronary angiography showed total occlusion of distal right coronary artery (E) which was successfully treated with stent implantation (F).

Fig. 2

Pre-intervention coronary angiography is shown during staged percutaneous intervention with low contrast volume (6 cc) (A) and pre-stent intravascular ultrasound images are shown (B-F). Minimal lumen area of ostial left circumflex artery was 2.5 mm2 (B) and the vessel size of distal reference segment in left circumflex artery was about 4.0 mm (C). The vessel size in the left main coronary artery was about 5.5 mm (D). Minimal lumen area of proximal left anterior descending artery was 2.4 mm2 (E) and the vessel size of distal reference segment in left anterior descending artery was about 3.8 mm (F). Optimal results were initially confirmed with post-stent intravascular ultrasound examination [minimal lumen area was 8.5 mm2 in left anterior descending artery (H) and 7.4 mm2 in ostial left circumflex artery (I)]. Then, final post-stent angiogram was performed after confirmation of optimal results of two stent implantation in left main bifurcation lesions with intravascular ultrasound (G).

Fig. 3

Transducer of intravascular ultrasound is located in left circumflex artery (arrow, A) and left anterior descending artery (arrow, B) on fluoroscopic images, which was useful to determine the distal landing zone of stent. Two stent technique in a culotte fashion was performed with fluoroscopic guidance and without use of contrast dye based on the angiographic and IVUS findings (C and D). After final kissing balloon inflation (E), final second angiography with 6 cc contrast injection revealed successful results (F).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download