Abstract

A 20-year-old female had undergone definitive surgical repair for pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum soon after birth. She was referred to our institution with the chief complaint of clubbing fingers. A thorough examination revealed platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome due to an interatrial right-to-left shunt through a secundum atrial septal defect. Percutaneous closure with an Amplatzer Septal Occluder resulted in resolution of the syndrome.

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome (POS) is characterized by dyspnea noted in an upright position and relieved in a supine position (platypnea), and oxygen desaturation noted in an upright position (orthodeoxia).1 It can be caused by an intracardiac shunt, an intrapulmonary shunt, or a ventilation-perfusion mismatch.1 Two clinical conditions must coexist in POS, including an anatomical component of an atrial septal defect (ASD), a patent foramen ovale (PFO), or a fenestrated atrial septal aneurysm, and a functional component of cardiac, pulmonary, abdominal, or other origin.1 The diagnostic criteria of POS include an interatrial communication, a right-to-left shunt, absence of pulmonary arterial hypertension and right atrial hypertension, orthodeoxia, and platypnea.2 Herein we report a 20-year-old female who presented POS with clubbing fingers and orthodeoxia insidiously two decades after reconstruction of right ventricular outflow tract for pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PA-IVS), and was treated by percutaneous closure of a secundum ASD with an Amplatzer Septal Occluder (ASO).

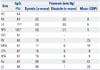

A 20-year-old female underwent reconstruction of right ventricular outflow tract for PA-IVS soon after birth. Postoperative follow-up was uneventful. She was referred to our hospital with the chief complaint of insidious clubbing fingers. Her family could not remember when her clubbing fingers appeared. At the outpatient clinic, neither lip cyanosis nor oxygen desaturation was discernible. At admission, she was 54 kg in weight and 168 cm in height. Pulse rate was 82/min, and respiratory rate 20/min. Hemoglobin was 14.9 gm/L. Clubbing fingers were remarkable (Fig. 1A). Peripheral pulse oximeter showed marked fluctuations of oxygen saturations (SpO2), ranging from 84% to 95% in the supine position and from 80% to 88% in the upright position. There was no pathological heart murmur. Liver and blood coagulation functions were normal. Initial trans-thoracic echocardiography (TTE) with bubble study in the supine position failed to detect any intracardiac shunt. However, TTE with bubble study performed in the seated position did reveal an interatrial right-to-left shunt (Fig. 1B). Hemodynamic data are summarized in Table 1. There was a step-down of oxygen saturation from the pulmonary vein to the left atrium, indicating an interatrial right-to-left shunt. Besides, there was no trans-atrial pressure gradient, right ventricular hypertension, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) with Doppler showed a secundum ASD with a right-to-left shunt. Balloon sizing showed an indentation of 21.84 mm in diameter (Fig. 1C). Before implantation, a bolus of 2000 units of heparin was infused into the delivery system. A 22-mm ASO was chosen to occlude this defect (Fig. 1D and E). After implantation, ICE showed complete occlusion (Fig. 1F). We wiggled the cable to test the stability and relieved the device smoothly. Interestingly, the anatomic lie of ASO was positioned more ventrally oblique in the present patient (Fig. 1G) than those in the usual patients with a secundum ASD (Fig. 1H). SpO2 of ascending aorta and left ventricle elevated to 99–100%. In a 24-month follow-up, she was free of POS.

There are four noteworthy implications to be highlighted. First, our patient met four of the five diagnostic criteria, including 1) existence of an interatrial communication, 2) right-to-left shunt, 3) no pulmonary hypertension or elevation of right atrial pressure, and 4) orthodeoxia (SpO2 <90%). However, she did not have platypnea at the time of diagnosis. Not all patients presented simultaneously with platypnea and orthodeoxia at first, and both of which can be detected only after performing postural change test.3 Platypnea may be difficult to discern without a careful evaluation of dyspnea.3 Orthodeoxia can be masked by profound cyanosis, or even overlooked in patients with only mild desaturation in the upright position, as seen in our patient with SpO2 of 80–88%. Hence, postural change test should be done, if there is a suspicion of POS. Our patient presented with marked fluctuations of SpO2 in the supine and sitting positions. We think that this phenomenon may be related to a dynamic flip-flap motion of the check valve that guards the interatrial septal defect. This aleatory or unpredictable factor may be culpable for the marked fluctuations of oxygen saturations in the supine and sitting positions.

Second, once the diagnosis of POS is established, the underlying mechanisms and clinical conditions must be carefully differentiated to guide treatment thereafter. It is important to search for not only cardiac maladies, but also concomitant pulmonary or abdominal pathology.12 TTE with bubble study is valuable in detecting interatrial right-to-left shunt, while trans-esophageal echocardiography is useful in assessing the anatomy of ASD/PFO with or without atrial septal aneurysm,4 prominent Eustachian valve,4 large aortic aneurysm,5 and extensive Chiari network with lipomatous atrial septal hypertrophy.6 Cardiac catheterization is the gold standard in diagnosing cardiac POS, by excluding right heart hypertension and confirming a step-down of SpO2 in the left atrium.4 Computed tomography can be used to identify distortion of the atrial septum caused by aortic aneurysm,5 or to discriminate POS of pulmonary, abdominal, and other origins.4

Third, the underlying pathogenesis of interatrial right-to-left shunt in the presence of normal pulmonary arterial pressure in our patient may be ascribed to 1) anatomic disarray of the septum primum which had been forced by severe tricuspid regurgitation in the setting of PA-IVS, bulged toward the left atrium, and redirected the inferior caval flow and tricuspid regurgitation shunting preferentially to the left atrium, and 2) long-term influence of decreased compliance of a relatively smaller right ventricle in spite of successful reconstruction of right ventricular outflow tract without significant pressure gradient.

Fourth, management of POS must be directed to the underlying pathology and clinical conditions. Most POS patients have a secundum ASD or a PFO.7 A large review of 157 POS patients, with an interatrial right-to-left shunt, indicates that percutaneous closure achieved successful closure or symptom resolution in 148 of 151 patients (98%).7 Interestingly, the anatomic lie of ASO in our patient was tilting more ventrally oblique. The interatrial opening in our patient would be smaller if we looked the atrial septum in front from the right atrium, and larger if we took a bird's-eye view from the ascending aorta.

In conclusion, clubbing fingers may herald full-fledged POS. Postural change test is essential to detect subtle orthodeoxia. TTE with bubble study is a useful tool in revealing an interatrial right-to-left shunt. Cardiac catheterization is the gold standard in diagnosing cardiac POS, and percutanous closure is the treatment of choice for cardiac POS with a secundum ASD or a PFO.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome treated by implantation of Amplatzer Septal Occluder (ASO). (A) Clubbing fingers were remarkable. (B) Contrast trans-thoracic echocardiography showed multiple bubbles in the right atrium and the right ventricle (open arrows), indicating the presence of interatrial right-to-left shunt. (C) Balloon sizing showed an indentation with a diameter of 21.84 mm. Intracardiac echocardiography showed (D) opening of left-side disc of ASO in the left atrium, (E) opening of right-side disc of ASO in the right atrium, and (F) complete occlusion of the secundum atrial septal defect after deployment of ASO. It is worthy of note that the ASO lie in (G) the present patient was somewhat more oblique than (H) the usual patients with a secundum atrial septal defect under fluoroscope (lateral 70 degrees; cranial 20 degrees). |

Table 1

Cardiac Catheterization in the Room Air and Supine Position

IVC, inferior vena cava; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RPV, right pulmonary vein; SVC, superior vena cava; RV, right ventricle; MPA, main pulmonary artery; LPA, left pulmonary artery; RPA, right pulmonary artery; Ao, aorta; LV, left ventricle; SpO2, oxygen saturation; EDP, end diastolic pressure.

*There was a step-down of oxygen saturation from the pulmonary vein to the left atrium, indicating an interatrial right-to-left shunt.

References

1. Cheng TO. Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome: etiology, differential diagnosis, and management. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 1999; 47:64–66.

2. Akin E, Krüger U, Braun P, Stroh E, Janicke I, Rezwanian R, et al. The platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014; 18:2599–2604.

3. Suzuki H, Ohuchi H, Hiraumi Y, Yasuda K, Echigo S. Effects of postural change on oxygen saturation and respiration in patients after the Fontan operation: platypnea and orthodeoxia. Int J Cardiol. 2006; 106:211–217.

4. Blanche C, Noble S, Roffi M, Testuz A, Müller H, Meyer P, et al. Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome in the elderly treated by percutaneous patent foramen ovale closure: a case series and literature review. Eur J Intern Med. 2013; 24:813–817.

5. Eicher JC, Bonniaud P, Baudouin N, Petit A, Bertaux G, Donal E, et al. Hypoxaemia associated with an enlarged aortic root: a new syndrome? Heart. 2005; 91:1030–1035.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download