MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this cross-sectional study, quantitative, analytical, and observational methodologies were used to assess patients that underwent one of three types of gastric restrictive surgery: LAGB, LGCP, or LSG at the Gil Medical Center (Gachon University, Incheon, Korea) from January 2012 to December 2013. These dates were selected in order to recruit patients within 2 years of surgery. Questionnaires were administrated to patients with an uncomplicated postoperative course pre- and postoperatively (at least 3 months after surgery) during follow-up outpatient visits or by e-mail, post, or telephone. We followed guidelines issued by the Asian Consensus Meeting on Metabolic Surgery (ACMOM 2008, Trivandrum, India) for body mass index (BMI) restriction by bariatric surgery (

http://www.acmoms.com/acmom_2008.html). Given the absence of an absolute medical contraindication, the surgical techniques used were based on patient preferences. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and all that underwent LGCP were specifically informed of its experimental nature. The ethical committee at our institution approved the study protocol.

Operative technique and postoperative management

All 85 operations were performed by a single laparoscopic surgeon (S.M.K.). The pars flaccida technique with three gastrogastric sutures was adopted for all gastric banding procedures. Band adjustment was serially performed at one month intervals until patients reached the 'green zone'. During LGCP, after gastrolysis of the greater omentum from the greater curvature of the stomach, a Bougie (36 Fr) was inserted by an anesthesiologist to guide the infolding procedure. Gastric infolding was performed using two layers of nonabsorbable sutures (inner interrupted and outer continuous 2-0 Ethibond®) from 3 cm above the pylorus to 2 cm below the esophagogastric junction. A gastrograffin UGI swallow study was performed within 48 hours of surgery to determine the presence of luminal obstruction or leakage. Patients were discharged after they tolerated a liquid diet (100 cc/hr). For LSG, after gastrolysis of the greater omentum from the greater curvature, a Bougie (36 or 40 Fr) was inserted to guide gastric resection, which was performed using five to seven 60 mm staples. A seroserosal reinforcement suture was placed using 2-0 Vicryl®. Fibrin glue and a JP drain were routinely used.

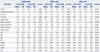

Analysis of surgical treatment outcomes and the questionnaire study

Data on patient numbers, operative procedures, genders, ages, perioperative BMIs, percentage excess weight losses (%EWL), and complications were collected during follow-up. Food tolerance and QoL were assessed using FTS, the 36-item gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI), and the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire. These three questionnaires were administrated to patients with an uncomplicated postoperative course pre- and postoperatively (at least 3 months after surgery) during follow-up outpatient visits or by e-mail, post, or telephone.

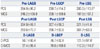

The food tolerance score (FTS) questionnaire

FTS is a self-administered, one page questionnaire that is used to evaluate degree of food tolerance following bariatric surgery.

10 Patient satisfaction regarding food intake is scored between 1 (very poor) and 5 (excellent) points, and food tolerance between 0 and 16 points for eight specific types of food. Tolerance of each food was awarded 2 points if the patient could eat it without difficulty, 1 point if the patient could eat it with some difficulties/restrictions, and 0 points if the patient could not eat it at all. Vomiting/regurgitation was scored between 0 and 6 points as follows: daily vomiting or regurgitation, 0 points; three or more times a week, 2 points; up to twice a week, 4 points; never, 6 points. Thus, scores varied between 1 and 27, where 27 indicated excellent food tolerance.

GI quality of life index (GIQLI)

GIQLI is an instrument that was designed in the early 1990s by Eypasch, et al.

11 to assess health-related QoL in clinical studies of GI disease and in daily clinical practice. The questionnaire measures the following four domains: GI symptoms (19 questions), physical function (PF) (7 questions), emotional function (5 questions), and social function (5 questions). Each question is scored from 0 to 4 (0 being the worst and 4 the best option). The maximum possible score is 144.

Short-form 36 health status survey (SF-36)

The SF-36 measures the following eight subscales: PF, role limitations due to a physical problem (RP), role limitations due to an emotional problem (RE), energy/fatigue (EF), emotional wellbeing (EWB), social functioning (SF), bodily pain (BP), and general health (GH). These eight subscales compose two distinct higher order summary scales: 1) the physical component summary scale (PCS), which is mainly based on PF, RP, BP, GH, and 2) the mental component summary scale (MCS), which is mainly based on RE, EF, EWB, and SF.

The Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) questionnaire was completed by all 85 patients before and after surgery. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests were used to determine the significances of intergroup differences with respect to demographic data, food tolerance, GIQLI scores, and SF-36 scores and component scale scores of SF-36. Significances (p<0.05) were adjusted using Bonferroni's post-hoc correction.

DISCUSSION

Gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy are well-established restrictive surgeries. Gastric banding has been popular since its introduction in the early 1990s due to the ease of the procedure, adjustability of stoma, portion control, and the weight loss achieved. Increases in HRQoL scores after gastric banding are most marked during the first postoperative months, and after 6 months, they increase more slowly and stabilize at around 1 year.12 Several authors have also claimed that general patient HRQoL after LAGB is significantly improved and maintained in the long term.

13141516171819 However, specific QoL studies that addressed food tolerance after LAGB have concluded it was less effective of all other procedures.

1020 In another study, symptom domain scores of the GIQLI were not found to be improved after LAGB.

21 During 7 years of post-LAGB management experience, we have frequently witnessed functional GI problems due to passage disturbance and proximal dilatation above the band and chronic problems due to infection and migration of the band system.

222324 More importantly, during the weight loss phase, many banded patients experienced dysphagia when eating solid regular food (regardless of weight loss) and frequent vomiting and reflux due to functional obstruction by the band system. For example, the mean±SD vomiting regurgitation sore (VRS) of LAGB in the present study was 2.13±1.67, which means that typically LAGB patients vomit or experience regurgitation three or more times per week. Consequently, the total FTS after LAGB (15.96±4.39) was lower than after LGCP or LSG. This finding is in line with those of other studies, which found that VRS and FTS were relatively low after LAGB.

102025 Furthermore, Schweiger, et al.

20 pointed out that this poor FTS after LAGB was sustained until the late postoperative period.

LSG was recently approved as a standalone procedure. According to recent worldwide statistics,

26 it is being increasingly adopted and the use of gastric banding is decreasing. Several studies have also shown that LSG results in superior early excess weight loss and eating quality than gastric banding.

272829 The results of our study support these assertions, as %EWL after LAGB and LSG were significantly different (65.4±27.0% vs. 82.7±21.7%, respectively). In addition, mean postoperative FTS and improvements in total GILQI after LAGB and LSG were also significantly different [15.96 vs. 21.33 (FTS), and -3.40 vs. 18.78 (Δ total GIQLI), respectively].

LGCP is an emerging restrictive bariatric procedure that successfully reduces gastric volume by plication of the gastric greater curvature. Furthermore, many acceptable short-term or mid-term treatment outcomes after LGCP have been recently published.

2345678 However, as far as quality of eating after LGCP is concerned, little is known and intractable vomiting appears to be a unique morbidity. Many patients experience nausea, vomiting, and sialorrhea during the immediate postop period due to an edematous gastric wall, which is not only uncomfortable, but also increases the incidences of adverse LGCP specific reactions, such as focal ischemic perforation,

4630 gastric obstruction,

346831 gastrogastric hernia (stitch burst),

8 and intragastric compartment syndrome.

30 Unfortunately, actual food tolerance and eating quality after LGCP have not been described, and thus, many bariatric surgeons are reluctant to perform the procedure due to reported variable responses after surgery. In the one study conducted on the topic,

5 Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQoL-Lite) was found to show significant improvement after 12 months. The present study is unique in that we investigated eating quality after LGCP and compared its results with those of gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy to determine whether LGCP is a clinically relevant form of restrictive surgery.

The main findings of the present study were as follows: first, mean total FTS after LGCP was located between those of LAGB and LSG (15.96±4.39, 20.95±4.30, and 21.33±2.74 for LAGB, LGCP, and LSG, respectively). In our subgroup analysis of total FTS, this tendency was maintained for specific items, such as specific food tolerance and vomiting/reflux scores. Furthermore, differences were statistically significant versus LAGB. In fact, 'satisfaction with current eating' score was highest in the LGCP group. Patients' comments regarding why they were satisfied with current eating were "satisfied with less hunger between meals," "I am satisfied with current portion control," "I feel full after eating a small amount of food," and "I can eat all types of food, but only in small amounts." These results are obviously due to the fact that LGCP and LSG involve no 'obstructing' foreign body (silicon band), and suggest that after LGCP, patients seem to tolerate almost all types of food and adopt a balanced diet from several months after surgery. This implies that LGCP, like LSG, is a more physiologic procedure than gastric banding. As far as VRS is concerned, LGCP was better than LAGB due to absence of frequent vomiting or reflux during eating. However, LGCP was found to be more associated with vomiting and reflux than LSG. In some patients after gastric plication, initial postop edema, luminal narrowing, and acid reflux continues for several postop months. We have witnessed by endoscopy in such patients that gastroesophageal reflux (GER) after LGCP is due to high intraluminal pressure and resulting 'transient LES insufficiency' rather than being due to a damaged anti-reflux mechanism, as suggested after LSG. Education on eating skills and the use of proton pump inhibitors and antiemetics usually resolve these problems. We found that the use of a 36 Fr Bougie, four point suture technique as described by El-Geidie and Gad-el-Hak,

32 and strict diet education during the immediate postop period are critical not only for minimizing vomiting, emesis, and sialorrhea, thereby reducing hospital stay, but also for minimizing VRS score, duration of PPI usage, and eventually total FTS after LGCP.

Second, the higher total GIQLI scores observed after surgery in the LGCP group lay between those of the LAGB and LSG groups. All patients showed improvements in the three domains of GH (social, physical, and emotional functions), although increases in symptom domain GIQLI scores were quite different in the LAGB, LGCP, and LSG groups (-8.84±7.76, -4.55±7.73, and 3.22±17.00, respectively). The amount of change in the symptom domain of the GIQLI is a key component of total GIQLI score, which is line with that observed by Overs, et al.,

25 who found that there exists a significant positive relationship between FTS and total GIQLI scores. In the present study, the LSG group had significantly higher symptom domain scores than the LAGB and LGCP groups. In fact, in the LAGB and LGCP groups, symptom domain GIQLI scores decreased after surgery. In the LAGB group, this decrease was evidently caused by frequent clogging of food, regurgitation, and an occasional tight gastric band. The observed reduction in symptom domain GIQLI scores after LGCP was an unexpected finding. Specific GI symptoms after LGCP reduced scores in the symptom domain, and these symptoms were mainly related to vomiting, slow food intake, acid regurgitation, and constipation, very much like those after LAGB. In addition, some of the patients in the LGCP group experienced new onset acid- or non-acid reflux after surgery, and patients in this group complained of food obstruction, vomiting, heartburn, and emesis. These symptoms are related to the small intragastric volume typical of the early postop period after LGCP, and relieve with time due to a gradual increase in gastric emptying due to physiologic dilatation of the plicated stomach. Therefore, we expect that symptom domain GIQLI scores will gradually increase with time after LGCP. On the other hand, Lee, et al.

33 observed that GIQLI scores remained similar before and after LAGB. In this previous study, the preoperative score was 110.8+15 points and became 116.2+13, 114.7+13, 108.5+14, and 107.2+17 at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively. The authors concluded although LAGB was successful in terms of weight loss and the resolution of co-morbidities, GIQLI did not improve, and that this feature constitutes a major disadvantage of LAGB. It would be valuable to compare symptom domain GIQLI scores (or total GIQLI scores) after LAGB and LGCP serially throughout the postoperative period (e.g., after the first and second postop years).

Third, scores of the eight subscales of the SF-36 were significantly improved after surgery. We found that compared to the LAGB group, patients in the LGCP and LSG groups showed significant increments in GH subscale scores postoperatively. The preoperative baseline survey showed that in LAGB patients subjective health status scores were higher than in the other two groups. In other words, patients in the LAGB group did not think that their GH status was as bad preoperatively or that their GH had been improved substantially after surgery. Changes in PF subscale scores were similar to the change of GH subscale scores. Improvement in EWB subscale scores deserves attention because LSG group patients showed significantly higher EWB subscale scores and greater increments in EWB scores after surgery. Excepting RP subscales, LGCP patients showed improvements in all subscales scores after surgery, and these improvements were located between those of LAGB and LSG patients. Thus, we found that aside from a sustained weight loss pattern and adjustability typical of gastric banding, improvements in GH related QoL after LAGB was rather suboptimal. The present study is unique in that for all eight subscales of the SF-36, improvements were investigated versus preoperative baseline values, which is more relevant in terms of clinical significance. When the eight subscales of the SF-36 were divided into two variables (MCS+PCS), patients in the LSG group were found to achieve significantly greater improvements in both CS scores than patients in the LAGB and LGCP groups. Therefore, although our cohort of patients showed that LSG patients were least healthy among three groups (lowest PCS, and MCS scores), perceived healthy statuses after surgery by individual patients was not significantly different from other surgery groups. Excess weight loss (%) was lower in the LAGB group than in the LGCP or LSG groups. Generally, if major complications do not occur, nadir body weight is achieved within up to 2 years after gastric banding, whereas a considerable proportion of patients that undergo LGCP reach nadir weight within the first postoperative year. Therefore, because of the short term observational design of the present study, we are not able to draw conclusions regarding the relative superiorities of the three procedures.

The present study has several limitations that deserve mention. First, it was not a randomized controlled study, and patients were allocated to study groups according to patient preferences, unless there was an absolute medical contraindication. Therefore, preoperative baseline GIQLI subdomain scores and SF-36 subscales and component summary scores differed in the three groups. However, unlike many other QoL studies with no preoperative comparison, we were able to compare groups based on improvements achieved after surgery using preoperative data. Nevertheless, further study is needed to determine the effects of individual surgeries on the QoLs of homogenous individuals in matched groups. Co-morbidities were not addressed by the QoL questionnaire, and we only used SF-36, which is the most widely used measure of GH-related QoL. However, IWQoL-Lite has been shown to be useful for assessing post-surgical changes in QoL and been reported to have greater sensitivity than SF-36 for obese patients.

Second, the effect of non-response bias cannot be excluded and the follow-up period was relatively short. However, little long-term outcome data is available after LGCP, and thus, more long-term QoL studies are warranted. As mentioned above, nadir body weight is known to be achieved at different times after specific types of surgery. One reason for this is that the principles of food restriction are somewhat different for gastric banding and gastric sleeve surgery. In general, given good follow-up and proper adjustment, LAGB patients maintain body weight with acceptable food tolerance and QoL without major complications. We did not observe any band slippage or erosion or port infection during the study period (up to 24.4 months postop) and still there has been long term data indicate high QoL and satisfaction after LAGB. It is clear that QoL after LAGB could be further compromised by major complications. As the present study involved a cross-sectional comparison, our data do not indicate how HRQoL scores change with time.

Third, the BMIs of patients enrolled in the present study were relatively low (<40 kg/m2). In Korea, the number of superobese and morbidly obese patients is relatively small. Furthermore, many observational studies have concluded that LGCP is maximally effective in patients with a BMI of <45 kg/m2. Therefore, the results of our study are not applicable to the superobese or morbidly obese.

Finally, although our study indicates that in the short term, LGCP compares well with LAGB and LSG in terms of food tolerance and QoL, we found nausea, vomiting, and sialorrhea were far more frequent after LGCP in hospital. Furthermore, LGCP has been associated with the unique morbidity of intractable vomiting,

313435 and thus, questionnaires were sent to patients at more than three months after surgery. During this period scheduled band adjustments were completed after LAGB, and postop gastric wall edema had almost subsided after LGCP and LSG. However, immediate postop status should be discussed with patients before gastric plication surgery because many patients comment that food tolerance (super-restriction) during the immediate postop period was more difficult than they had expected. Furthermore, after restrictive surgery, patient education and compliance with eating are important. Nonetheless, it is clear that food tolerance and QoL in a non-compliant patient are likely to be suboptimal, regardless of surgery type.

In summary, the present study establishes that after LGCP food tolerance and QoL improvements are 'borderline' and lie between those of gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy in the short-term. In the near future, long-term, comparative studies should be undertaken on different restrictive surgeries as these will undoubtedly help potential patients choose one procedure over another.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download