Abstract

Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP) in patients with HIV infection can, in rare cases, present with pulmonary nodules that histologically involve granulomatous inflammation. This report describes an intriguing case of granulomatous PJP with pulmonary nodules after commencing antiretroviral therapy (ART) in an HIV-infected patient without respiratory signs or symptoms. Diagnosis of granulomatous PJP was only achieved through thoracoscopic lung biopsy. This case suggests that granulomatous PJP should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary nodules in HIV-infected patients for unmasking immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome manifestation after initiation of ART.

Pneumocystis jirovecii (P. jirovecii) pneumonia (PJP) is a major opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patients and should be considered as a possible diagnosis in patients with HIV infection who have respiratory symptoms with abnormal chest radiograph findings. Generally, patients with PJP infections have radiological findings of diffuse bilateral ground-glass opacity with or without consolidation and are diagnosed on the basis of visualization of pneumocystis organisms in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Granulomatous PJP is an unusual histopathologic finding that only occurs in 4–5% of patients with or without HIV infection.12 A previous study suggested that the development of granulomatous PJP may be associated with the host immune response rather than microbiological factors, such as P. jirovecii genotypes.3 However, there are few case reports of granulomatous PJP in HIV-infected patients undergoing immunologic recovery following antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Here we report a unique case of granulomatous PJP infection that presented as multiple pulmonary nodules and was barely diagnosed via thoracoscopic lung biopsy in an HIV-infected patient after initiation of ART and prophylaxis.

A 47-year-old male with HIV infection attended the outpatient clinic with a seven-day history of dry cough. The patient had a history of treated esophageal varices due to alcoholic liver cirrhosis 3 months prior, when he was incidentally discovered to be infected with HIV. One month prior to this report, he was started on ART [lamivudine 150 mg twice daily (b.d.), zidovudine 300 mg b.d., lopinavir/ritonavir 400/100 mg b.d.] and prophylactic therapy for P. jirovecii infection [one trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) single strength tablet once daily (q.d.)].

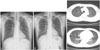

The physical chest examination was initially unremarkable, and a chest X-ray was normal (Fig. 1A). At baseline, before the initiation of ART, a complete blood count showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 4110/µL, thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 80×103 cells/µL, and a hemoglobin (Hb) concentration of 10.0 g/dL. The patient's CD4+ lymphocyte count was 75 cells/µL, and the HIV RNA titer was 350000 IU/mL.

The patient underwent repeat chest radiography 3 weeks after the initiation of ART. Newly developed multiple nodular lesions were observed on the right lower lung field (Fig. 1B). Multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules were also visible on a computed tomography scan (Fig. 1C). These findings would suggest tuberculosis or a non-infectious pulmonary infiltration, such as lymphoma or Kaposi's sarcoma. The patient's body temperature was normal, and oxygen saturation with pulse oximetry was 99% on room air. A complete blood count showed a WBC count of 3460 cells/µL, an Hb concentration of 12.3 g/dL, and a platelet count of 113×103 cells/µL with 82% neutrophils. A chemistry analysis demonstrated an elevated C-reactive protein concentration of 1.56 mg/dL. Bronchoscopy with BAL was conducted. No pneumocystis organisms were identified via a Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain. The results of a bacterial culture and acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear were also negative. A wedge resection of the right lower lobe of the lung performed through video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery revealed chronic granulomatous inflammation without necrosis, which could mimic the appearance of tuberculosis (Fig. 2A). However, no mycobacterial organisms were found via AFB staining. Furthermore, a mycobacterial culture of lung tissue was negative after 6 weeks. Several clusters of P. jirovecii within the granulomatous inflammation were identified using a GMS stain (Fig. 2B). The patient was treated successfully with TMP-SMX (four single strength tablets three times daily) over a 21-day course. The patient continued receiving ART and secondary prophylaxis of P. jirovecii and did not develop any further opportunistic infections during follow-up.

This report presents the case of an HIV-infected patient with granulomatous PJP unmasked as an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) manifestation shortly after initiation of ART and prophylactic therapy against PJP. The radiological and histological findings of this case were distinct from common manifestations in patients with PJP. The chest radiograph revealed multiple nodular lesions, and P. jirovecii was not identified in BAL fluids. Granulomatous PJP was only detected during thoracoscopic lung biopsy. BAL is considered to be highly sensitive as a diagnostic procedure of PJP (>90%).4 However, the procedure is known to have a low diagnostic yield in cases of granulomatous PJP. Therefore, open lung biopsies have the possibility of improving diagnostic sensitivity.2

Granulomatous PJP is principally noted in HIV-infected patients and infrequently in other immunocompromised patients who are undergoing immunologic recovery. Therefore, it has been suggested that host predisposition may be implicated in the development of granulomatous inflammation against P. jirovecii. HIV-infected patients undergo immunologic recovery through memory T cell redistribution following ART for up to 6 months.5 This case is similar to previously reported cases of granulomatous PJP in HIV-infected patients following ART (Table 1).6789101112 In the era of highly active ART, there have only been three case reports of granulomatous PJP as presentation of IRIS during the course of therapy. Risk factors for granulomatous PJP in HIV-infected patients described in previous reports include the use of nebulized pentamidine for PJP prophylaxis, as well as IRIS. Previously reported cases were all characterized by low baseline CD4+ cell counts and high HIV viral loads before the initiation of highly active ART. These features have also been identified as risk factors for the development of IRIS. Pneumocystis-IRIS is known to be an unusual form of IRIS, generally occurring 1 week to 1 month after the initiation of highly active ART.1314 Thus, granulomatous PJP as an unmasking or paradoxical form of IRIS should be considered in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active ART who have a high risk for IRIS. The difference between our case and previously reported cases is that this patient was prescribed TMP-SMX (one single strength tablet q.d.) for PJP prophylaxis. The patient recounted that medication adherence was >90%. TMP-SMX in the prophylaxis of PJP is the drug of choice, with an efficacy of >90%.15 Non-adherence rather than drug failure may contribute to the development of breakthrough PJP in HIVinfected patients prescribed TMP-SMX.16 Thus, we assume that immune reconstitution in a high pneumocystis antigen burden setting may lead to the progression of clinically apparent PJP in a patient with subclinical P. jirovecii infection.

This case suggests that a diagnosis of granulomatous PJP should be considered in HIV-infected patients with newly developed pulmonary nodules in order to unmask IRIS manifestation after the initiation of ART.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Plain chest radiograph within normal limits. (B) Plain chest radiograph showing newly developed multiple nodular lesions in the right lower lung field. (C) Chest CT scans showing multiple nodular lesions in the right and left lower lobes of the lung. |

| Fig. 2(A) Chronic granulomatous inflammation seen in the lung parenchyma, which filled with secretory materials in alveolar spaces (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200). (B) Pneumocystis jirovecii cysts, 5–8 µm in size, seen with an alveolar plaque stained using Gomori methenamine silver stain (×800). |

Table 1

Summary of Reported Cases on Granulomatous PJP in HIV-Infected Patients after Initiation of ART

| YearRef | Age/sex | Previous history of PJP | Other HIV/AIDS associated illness | ART | Prophylaxis | Granulomatous PJP onset after initiation of ART | Pre-treatment CD4+ cell count (cells/µL) | Pre-treatment HIV RNA titer (IU/mL) | Radiological findings | BAL | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19886 | 38/M | Yes | CMV retinitis | AZT | Nebulized pentamidine | 3 months | NM | NM | Bilateral interstitial infiltrates | Negative | Died |

| 34/M | Yes | No | AZT | Nebulized pentamidine | 3 months | NM | NM | Bilateral diffuse nodular lesions | NA | Recovered | |

| 19897 | 44/M | Yes | No | AZT | Nebulized pentamidine | 1 yr | NM | NM | A nodular lesion with cavitation | NA | Died |

| 19908 | 45/M | Yes | Kaposi's sarcoma | AZT | Nebulized pentamidine | 4 months | NM | NM | Bilateral interstitial shadow with some nodular lesions | Negative | Recovered |

| 19969 | 32/M | No | No | AZT | No | Unknown | 64 | NM | Bilateral diffuse nodular lesions | Negative | Recovered |

| 200210 | 40/M | Yes | No | d4T/3TC/NFV | No | 6 wks | 20 | 1.9×105 | A nodular lesion and atelectasis | Negative | Recovered |

| 200411 | 35/M | No | Mycobacterium xenopi pneumonia | AZT/3TC/NFV | Nebulized pentamidine | 3 wks | 20 | 1.54×105 | Bilateral apical consolidation with multiple nodular lesions | Negative | Recovered |

| 201112 | 40/M | Yes | No | Unnamed HAART | Discontinued TMP/SMX | 4 months | 16 | 5×106 | Multiple nodules with cavitary lesions | Negative | Recovered |

| Present case | 47/M | No | No | AZT/3TC/boosted LPV | TMP/SMX | 3 wks | 75 | 3.5×105 | Multiple nodular lesions | Negative | Recovered |

Ref, references; 3TC, lamivudine; ART, antiretroviral therapy; AZT, zidovudine; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; CMV, cytomegalovirus; d4T, stavudine; HAART, highly active ART; LPV, lopinavir; NA, not available; NM, not mentioned; NFV, nelfinavir; PJP, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; TMP, trimethoprim; SMX, sulfamethoxazole.

References

1. Travis WD, Pittaluga S, Lipschik GY, Ognibene FP, Suffredini AF, Masur H, et al. Atypical pathologic manifestations of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Review of 123 lung biopsies from 76 patients with emphasis on cysts, vascular invasion, vasculitis, and granulomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990; 14:615–625.

2. Hartel PH, Shilo K, Klassen-Fischer M, Neafie RC, Ozbudak IH, Galvin JR, et al. Granulomatous reaction to pneumocystis jirovecii: clinicopathologic review of 20 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010; 34:730–734.

3. Totet A, Duwat H, Daste G, Berry A, Escamilla R, Nevez G. Pneumocystis jirovecii genotypes and granulomatous pneumocystosis. Med Mal Infect. 2006; 36:229–231.

5. Autran B, Carcelain G, Li TS, Blanc C, Mathez D, Tubiana R, et al. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 1997; 277:112–116.

6. Blumenfeld W, Basgoz N, Owen WF Jr, Schmidt DM. Granulomatous pulmonary lesions in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and Pneumocystis carinii infection. Ann Intern Med. 1988; 109:505–507.

7. Klein JS, Warnock M, Webb WR, Gamsu G. Cavitating and noncavitating granulomas in AIDS patients with Pneumocystis pneumonitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989; 152:753–754.

8. Birley HD, Buscombe JR, Griffiths MH, Semple SJ, Miller RF. Granulomatous Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Thorax. 1990; 45:769–771.

9. Flannery MT, Quiroz E, Grundy LS, Brantley S. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia with an atypical granulomatous response. South Med J. 1996; 89:409–410.

10. Takahashi T, Nakamura T, Iwamoto A. Reconstitution of immune responses to Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with HIV infection who receive highly active antiretroviral therapy. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 2002; 112:59–67.

11. Chen F, Sethi G, Goldin R, Wright AR, Lacey CJ. Concurrent granulomatous Pneumocystis carinii and Mycobacterium xenopi pneumonia: an unusual manifestation of HIV immune reconstitution disease. Thorax. 2004; 59:997–999.

12. Sabur N, Kelly MM, Gill MJ, Ainslie MD, Pendharkar SR. Granulomatous Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia associated with immune reconstituted HIV. Can Respir J. 2011; 18:e86–e88.

13. Wu AK, Cheng VC, Tang BS, Hung IF, Lee RA, Hui DS, et al. The unmasking of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia during reversal of immunosuppression: case reports and literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2004; 4:57.

14. Müller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, Egger M. Ie-DEA Southern and Central Africa. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010; 10:251–261.

15. Calderón EJ, Gutiérrez-Rivero S, Durand-Joly I, Dei-Cas E. Pneumocystis infection in humans: diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010; 8:683–701.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download