Abstract

The recently introduced da Vinci Single-Site® platform offers cosmetic benefits when compared with standard Multi-Site® robotic surgery. The innovative endowristed technology has increased the use of the da Vinci Single-Site® platform. The newly introduced Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver has made it feasible to perform various surgeries that require multiple laparoscopic sutures and knot tying. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy is also a type of technically difficult surgery requiring multiple sutures, and there have been no reports of it being performed using the da Vinci Single-Site® platform. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of robotic single-site (RSS) sacrocolpopexy, and I found this procedure to be feasible and safe. All RSS procedures were completed successfully. The mean operative time was 122.17±22.54 minutes, and the mean blood loss was 66.67±45.02 mL. No operative or major postoperative complications occurred. Additional studies should be performed to assess the benefits of RSS sacrocolpopexy. I present the first six cases of da Vinci Single-Site® surgery in urogynecology and provide a detailed description of the technique.

Minimally invasive surgery has substantially evolved in recent decades and can now provide rapid recoveries and excellent cosmetic results for the patients. Single-port laparoscopic surgery (SPLS), also known laparoendoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) has been developed to provide further cosmetic benefits; however, several technical challenges have limited the range of feasible operations.1 Robotic surgery offers excellent ergonomic operating conditions for the surgeon;23 however, the typical Multi-Site® robotic surgery involves a 12-mm port and three 8-mm ports. The da Vinci Single-Site® platform was developed to provide the benefits of robotic surgery in combination with the cosmetic benefits of single-port surgery. However, the lack of endowristed technology had been an obstacle to the use of robotic single-site (RSS) surgery for many types of laparoscopic surgery. The recently introduced Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver has made it possible to perform surgeries that require multiple laparoscopic sutures and knot tying, such as laparoscopic myomectomy4 and sacrocolpopexy as described in this initial report. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) is considered to be one of the most promising surgical options for patients with pelvic organ prolapse (POP);56 however, this procedure is somewhat difficult, as it requires multiple sutures and dissection of the presacral space. Therefore, very few LESS sacrocolpopexies have been reported, and the surgeries that have been reported were performed with a simplified knotless technique involving polymeric clips rather than sutures.7 Herein, I describe our initial clinical experience with and technique for RSS sacrocolpopexy.

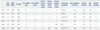

A total of six cases of advanced POP of apical type underwent RSS sacrocolpopexy. One case was vaginal vault prolapse, and I performed RSS sacrocolpopexy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The remaining five cases were uterine prolapse requiring RSS supracervical hysterectomy accompanied with sacrocolpopexy. The characteristics of patients and operations are summarized in Table 1.

The surgical procedures of RSS supracervical hysterectomy and sacrocolpopexy were as follows. After anesthetizing and draping the patient, a RUMI Arch™ Uterine Manipulator (CooperSurgical, Inc., Trumbull, CT, USA) was placed, and a Foley catheter was inserted into the bladder. The da Vinci Single-Site® platform was applied with a specialized silicone port and a curved cannula with a flexible instrument for RSS surgery. A vertical 2.5-cm transumbilical skin incision was created, and the fascia layer was opened in same direction using the open Hasson technique. The total length of this umbilical incision was 2.5 cm at the level of the skin and approximately 3 cm at the level of the underlying fascia and peritoneum. I inserted a size S Alexis® wound protector (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa, Margarita, CA, USA) into the fascial opening to facilitate the removal of the specimen during the final procedure of the surgery. The silicon port for the da Vinci Single-Site® was inserted through the Alexis-applied opening using long Kelly forceps and an Army-Navy retractor (Fig. 1A). The scars at the end of the surgery and at 4 weeks after the operation are illustrated in Fig. 1B and C. A pneumoperitoneum was created via carbon dioxide gas inflation to 12 mm Hg. A camera with a 30° down scope was inserted and localized to the fundus of the uterus after inserting the 8.5-mm cannula for the robotic laparoscope. The patient table was tilted into the Trendelenburg position and rolled to the left to laterally retract the right colon in order to facilitate the dissection of the presacral space (Fig. 1D and E). I used the central docking type for the docking of the da Vinci Si system (Intuitive Surgical, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) (Fig. 1D). The robotic arms were docked to the camera port, and two 250-mm long curved cannulas were inserted instead of 300-mm long cannulas, as the procedure occurred in the presacral area. A 5-mm accessory trocar was inserted into the silicon port. Flexible robotic instruments (a monopolar hook and fenestrated bipolar forceps) were mounted through the curved cannulas, and the robotic system provided a switching motion between right-hand and left-hand orientations.

The round ligaments were ligated bilaterally, and the retroperitoneal space was developed. After the identification of the ureters, the infundibulopelvic ligaments were skeletonized, coagulated, and ligated. A bladder flap was created using the monopolar hook, and the uterine arteries were skeletonized and cauterized with the bipolar forceps. After the bladder was dissected, a circumferential incision at the level of the isthmic portion was made with the monopolar hook instrument. The uterus and both adnexae were placed into an Endopouch® specimen retrieval bag (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). I converted the 5-mm accessory port to a 10-mm port in order to facilitate the insertion and removal of the needles for the intracorporeal suturing. The resected surface of the cervix was sutured using continuous running 0-V Loc™ sutures (Covidien, Dublin, Ireland). The redundant intraperitoneal fat of the anterior abdominal wall obscuring the operation field was temporarily sutured and tied to the anterior abdominal wall with 2-0 PDS™ sutures (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). A peritoneal incision was created to expose the sacral promontory and extended down to the vault. Anterior and posterior vaginal dissection was performed up to 5 cm long. Drawing back the curved trocars by about 30 mm lengthwise made it easy to dissect the presacral area. This simple procedure enabled us to have ample space for a presacral approach. A Y-shaped partially absorbable polypropylene mesh (Seratex® PA B2 type, Serag-Wiessner KG, Naila, Germany) was inserted through the 8.5-mm camera port and affixed to the anterior and posterior surfaces of the vagina in rows of two for a total of eight sutures per side. Three sutures were also applied to attach the mesh to the remaining cervix. Intracorporeal knot tying was performed with vertical mattress CV-3 Gore-Tex suture (WL Gore & Associates, Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA) to affix the mesh. Rotation of the camera to 180° (upside-down) gave us a better view during the suturing of the mesh to the posterior vaginal wall. To adjust the mesh tension, an Auto Suture Surgical Intestinal Colorectal Esophageal Reusable EEA™ Sizer was inserted vaginally and used to lift the cervix upward to ensure that the tension was adequate, and I brought the proximal end of the mesh to the longitudinal ligament of the sacrum by grasping it with bipolar forceps. The proximal end of the mesh was affixed to the sacral promontory with three stitches, and the redundant end of the mesh was excised with conventional laparoscopic scissors that were inserted through the 10-mm accessory trocar. The peritoneal incision was closed to cover the mesh using a running 2-0 PDS™ suture (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). The mesh was sutured to the cervix and sacrum using the Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver in a two-to-seven-o'clock direction (Fig. 2A). I found that when I needed to place a suture through a hard structure, the best technique was to direct the needle from the two-o'clock to the seven-o'clock position given the limited angulation and rotation of the Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver relative to the mega needle driver used in the Multi-Site® da Vinci system (180 degrees versus 540 degrees). I counted the numbers of used needles and poked them into the fat layer of the right lower abdominal wall rather than immediately removing them after finishing the sutures (Fig. 2B). I found that when I attempted to remove the needles thorough the silicon port used for the RSS operation, the silicon port partially blocked the path for the removal of the curved needles, whereas the silicon port did not block the path when I inserted the curved needles as shown in the schematic drawing in Fig. 3. After the de-docking of the da Vinci Si system, the silicon port for the RSS operation was removed. A surgical glove was applied to the Alexis®, and the 10-mm and 5-mm trocars for the da Vinci system were re-inserted into the fingers of the glove. At this step, I changed the patient's position to a neutral dorsal Lithotomy position without tilting her to the left. The 5-mm laparoscope was inserted through the trocar, and all of the needles used for the intracorporeal suturing were removed easily through the incision slit in the fingers of the glove port. The specimen in the Endopouch® was also easily removed from the peritoneal cavity through the Alexis® after morcellation with a knife in the bag. The fascia was closed with absorbable interrupted sutures, and subcutaneous closure was achieved with absorbable sutures.

The mean operative time for the RSS sacrocolpopexy was 122.17±22.54 minutes, and the mean blood loss was 66.67±45.01 mL. No cases were converted to laparotomy or laparoscopy. Among the six patients, three (cases 3, 4, and 6) complained of urinary stress incontinence, and this was demonstrated as urodynamic stress incontinence on a preoperative urodynamic study. Concomitant transobturator vaginal tape surgery was performed for those cases. The postoperative courses were uneventful, and the mean hospital stay was 3.33±0.51 days (Table 1). At the 1- and 6-week postoperative follow-up visits, no complications were observed, and the POP-Q stage was 0. The follow-up period for case 5 was 10 weeks and was 5 weeks for case 6. There were no recurrences of POP in any of the cases. The final scars at the end of surgery were less than 2.5 cm in length (Fig. 2D). All patients were satisfied with the outcome of the RSS sacrocolpopexy. Case 1 complained of dull back pain and constipation; however, the symptoms had resolved by 2 weeks after the operation with the ingestion of laxatives. Case 1 had chronic constipation preoperatively, and this was aggravated in the acute postoperative period. No other major or minor complications were noted during the follow-up period.

SPLS has caused a major paradigm shift in laparoscopic surgery in recent years. The poor ergonomic surgical conditions of SPLS have been improved by the development of numerous types of equipment to minimize hand collision and facilitate gas evacuation. However, certain types of surgery that require multiple sutures and knots are nevertheless thought to be challenging in terms of single-port laparoscopic surgery.89 LSC for POP is a good example of this type of technically difficult surgery. However, the difficulty of applying multiple sutures can be overcome by using the newly introduced Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver. The traditional approach to abdominal SC is effective for apical prolapse; however, the operative scarring and hospital stay time are remarkably decreased via the use of LSC as reported by Nezhat, et al.,10 based on an initial case series in 1994.

Recently, Barboglio, et al.11 retrospectively reviewed 127 cases of robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (RALS) from a single institution and concluded that RALS is a safe and effective surgical therapy for the management of symptomatic apical POP. One meta-analysis also concluded that RALS is an effective surgical treatment for apical prolapse, with a high anatomic cure rate and a low rate of complications.12 In terms of single-port surgeries, the robotic system with the newly introduced Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver provides a much more stable environment for intracorporeal suturing and tying than laparoscopic surgery. Certain gynecologic operations, including RSS myomectomy, have successfully been performed with the da Vinci Single-Site® platform.41314 The present report is the first description of the use of this platform for the treatment of urogynecologic problems. To decrease the operation time and facilitate the RSS sacrocolpopexy, I suggest the following technical tips: 1) use a wound protector prior to applying the silicon port for the da Vinci Single-Site® platform; 2) temporarily suture the redundant intraperitoneal fat of the anterior abdominal wall that obscures the operative field to ensure a clear operative field; 3) draw back the curved trocar for procedures on the presacral area; 4) insert the needle in the two-to-seven-o'clock direction using the Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver; 5) rotate the camera 180° for procedures on the posterior vaginal wall; 6) apply a glove port after removing the silicon port for the da Vinci Single-Site® platform; and 7) remove the needles used for intracorporeal suturing after applying the glove port rather than immediately after completing the suturing. The limitations of this study were as follows: 1) a relatively short follow-up period; 2) a single surgeon's experience at a single institution; 3) the relatively thin bodies of the patients, resulting in a lack of evidence for the feasibility of RSS sacrocolpopexy in obese POP patients; and 4) the lack of clinical studies demonstrating the effectiveness of RSS sacrocolpopexy when compared with robotic multi-site sacrocolpopexy.

In conclusion, RSS sacrocolpopexy with the Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver is a feasible and safe procedure. This technique makes the use of single-port surgery possible even for patients with advanced POP. I believe that the technical tips suggested in this technical report will be helpful for performing successful RSS sacrocolpopexy. Multicenter studies investigating the cost effectiveness, long-term effectiveness, and safety of RSS sacrocolpopexy should be conducted to determine the feasibility of the widespread application of this technique, particularly among young women with advanced POP, as this technique has the advantage of minimal postoperative scarring.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Silicon port for the da Vinci Single-Site® inserted through the Alexis-applied intraumbilical opening. (B) Final scar at the end of surgery. (C) The scar at postoperative 6 weeks. (D) Centrally docked da Vinci Si system. (E) Patient table tilted into the Trendelenburg position and rolled to the left for the retraction of the right colon. |

| Fig. 2(A) Insertion of the needle in the two-to-seven-o'clock direction using the Single-Site® Wristed Needle Driver. (B) The needles used for the intracorporeal suturing were poked into the fat layer of right lower abdominal wall rather than being removed immediately after the completion of the suturing. |

| Fig. 3Schematic drawing representing the insertion and removal of the curved needle through the accessory port positioned in the silicon port for the Robotic Single Site Surgery. (A) Silicon port not obscuring the insertion path of the curved needle. (B) The silicon port can obscure the removal path of the curved needle. |

Table 1

Patient Characteristics and Operation Related Variables

BMI, body mass index; op, operation; POP-Q, pelvic organ prolapse quantitation; EBL, estimated blood loss; SH, supracervical hysterectomy; BS, bilateral salpingectomy; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; TOT, transobturator vaginal tape; N/A, not available.

*Follow-up period less than 8 weeks, †Follow-up period less than 12 weeks.

References

1. Eisenberg D, Vidovszky TJ, Lau J, Guiroy B, Rivas H. Comparison of robotic and laparoendoscopic single-site surgery systems in a suturing and knot tying task. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27:3182–3186.

2. Gargiulo AR. Computer-assisted reproductive surgery: why it matters to reproductive endocrinology and infertility subspecialists. Fertil Steril. 2014; 102:911–921.

3. Liu H, Lawrie TA, Lu D, Song H, Wang L, Shi G. Robot-assisted surgery in gynaecology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 12:CD011422.

4. Lewis EI, Srouji SS, Gargiulo AR. Robotic single-site myomectomy: initial report and technique. Fertil Steril. 2015; 103:1370–1377.

5. Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 4:CD004014.

7. Tobias-Machado M, Chicoli FA, Costa RM Jr, Carlos AS, Bezerra CA, Longuino LF, et al. LESS sacrocolpopexy: step by step of a simplified knotless technique. Int Braz J Urol. 2012; 38:859–860.

8. Nam EJ, Kim SW, Lee M, Yim GW, Paek JH, Lee SH, et al. Robotic single-port transumbilical total hysterectomy: a pilot study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2011; 22:120–126.

9. Escobar PF, Knight J, Rao S, Weinberg L. da Vinci® single-site platform: anthropometrical, docking and suturing considerations for hysterectomy in the cadaver model. Int J Med Robot. 2012; 8:191–195.

10. Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 1994; 84:885–888.

11. Barboglio PG, Toler AJ, Triaca V. Robotic sacrocolpopexy for the management of pelvic organ prolapse: a review of midterm surgical and quality of life outcomes. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014; 20:38–43.

12. Hudson CO, Northington GM, Lyles RH, Karp DR. Outcomes of robotic sacrocolpopexy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014; 20:252–260.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download