Abstract

There are several reports to demonstrate that rifampicin, a major anti-tuberculosis agent, is associated with some adverse renal effects, with a few cases of rifampicin-induced minimal change disease (MCD). In the present case, a 68-year-old female presented with nausea, vomiting, foamy urine, general weakness and edema. She had been taking rifampicin for 4 weeks due to pleural tuberculosis. The patient had no proteinuria before the anti-tuberculosis agents were started, but urine tests upon admission showed heavy proteinuria with a 24-h urinary protein of 9.2 g/day, and serum creatinine, albumin, and total cholesterol levels were 1.36 mg/dL, 2.40 g/dL, and 283 mg/dL, respectively. MCD was diagnosed, and the patient achieved complete remission after cessation of rifampicin without undergoing steroid therapy.

Rifampicin is one of the standard drugs used to treat tuberculosis, however, has been reported to induce some adverse renal effects.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 The most frequent form of nephrotoxicity is a syndrome consisting of acute renal failure with pathological findings of tubular necrosis, while other forms of nephrotoxicity include interstitial nephritis with or without mild glomerular lesions, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and light chain proteinuria.2 Rifampicin-associated nephrotic syndrome has been published, including cases of rifampicin-induced minimal change disease (MCD).4,7,9 Generally, MCD is treated with glucocorticoids,11,12 and rifampicin-induced MCD was treated with a steroid in a previous case.9 Herein, however, we report a patient with MCD after rifampicin treatment, which was improved after rifampicin cessation without steroid therapy.

A 68-year-old female was admitted to the hospital because of a 5-day history of left pleuritic chest pain. She had no other relevant medical history except for a ten-year history of hypertension. On admission, her blood pressure was 146/70 mm Hg and her body temperature was 36.9℃. Physical examination was unremarkable, and urinalysis did not reveal any abnormal findings. Laboratory findings were as follows: hemoglobin 11.7 g/dL, hematocrit 32.7%, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 6.9 mg/dL, serum creatinine 0.74 mg/dL, sodium 130 mEq/L, potassium 3.9 mEq/L, total protein 5.6 g/dL, albumin 3.9 g/dL, and total cholesterol 167 mg/dL. According to chest X-ray, a pleural effusion was present in the left lower lobe. The pleural fluid (PF) was exudative, and PF analysis showed a pH of 7.4, total protein of 5800 mg/dL, albumin of 3200 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase of 679 IU/L, and glucose of 92 mg/dL. In addition, the white blood cell (WBC) count was 3879/mm3 with 99% mononuclear cells, and adenosine deaminase (ADA) was shown to be 104.0 IU/L in the PF. Pleural biopsy and pleural cytology were negative for malignancy. Based on the exudative characteristics and the high ADA level in the PF, pleural tuberculosis was suspected and anti-tuberculosis treatment was started. Treatment comprised rifampicin 600 mg/day, isoniazid 300 mg/day, ethambutol hydrochloride 1200 mg/day, and pyrazinamide 1500 mg/day.

During the 4-week anti-tuberculosis therapy regimen, the patient developed nausea, vomiting, general weakness, and edema. Urinalysis revealed 4+proteinuria with a few transitional epithelial cells, some coarse granular casts, and many mucous threads. According to a 24-h urine collection, protein and albumin values were 9.2 and 6.2 g/day, respectively. Laboratory findings were as follows: hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL, WBC 5490/mm3, BUN 33.2 mg/dL, serum creatinine 1.36 mg/dL, creatinine clearance 39 mL/min, total protein 5.6 g/dL, albumin 2.4 g/dL, serum aspartate aminotransferase 282 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase 282 IU/L, normal total bilirubin, and a total cholesterol of 283 mg/dL. Antinuclear antibody and P-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) and C-ANCA were all negative with normal serum complement levels.

According to a renal biopsy, MCD was present with focal thinning of the glomerular basement membrane (Fig. 1A). Non-sclerotic glomeruli were normocellular without mesangial expansion, and the tubules showed minimal atrophy and mild focal tubular injury. Additionally, the interstitium was widened by minimal fibrosis, and no depositions of immunoglobulins or complement components were observed in the glomeruli. Electron microscopy showed the podocyte foot processes to be diffusely effaced (Fig. 1B).

Due to toxic hepatitis, rifampicin and isoniazid were discontinued, but ethambutol hydrochloride and pyrazinamide were maintained. Moxifloxacin was added after 1 week, and isoniazid was added after 2 weeks. The pleural tuberculosis was well controlled with isoniazid, ethambutol hydrochloride, and moxifloxacin thereafter.

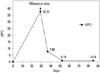

When her diagnosis was confirmed to be MCD, we determined to use steroid therapy at first. However, she was afraid of adverse effects of steroid treatment and asked us to observe closely. Moreover, we found out that heavy proteinuria was developed after using anti-tuberculosis agents. In addition, hepatitis also occurred after anti-tuberculosis agents started, and then we had to stop rifampicin and isoniazid agents. Fortunately, she improved spontaneously without steroid use only after quitting rifampicin. Therefore, we observed and followed up continuously. Her nausea, vomiting, and general edema improved and her body weight recovered from 68 kg to 63 kg at 3 weeks after rifampicin discontinuation, and a random urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 0.14 at 8 weeks (Fig. 2). Furthermore, her serum albumin and cholesterol levels were shown to be 3.9 g/dL and 180 mg/dL, respectively, 8 weeks after stopping rifampicin.

Rifampicin is a commonly used anti-tuberculosis agent, and it has been associated with several nephrotoxicities.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 Although there are a few case reports of nephrotic syndrome in patients using rifampicin, rifampicin-induced MCD reaching complete remission without steroid therapy has not yet been reported.4,7,9 Thus, we described herein a case of MCD that developed after rifampicin treatment that resolved after cessation of rifampicin without steroid therapy.

From a clinical perspective, apparently idiopathic MCD in some cases, compared with secondary MCD, may in fact represent a lesion arising secondary to an extraglomerular disease process. In many instances, the association between the extraglomerular disease process and MCD is quite obvious; on the other hand, however, the clinical findings of the underlying extraglomerular disease process can be quite subtle. According to Glassock13 secondary MCD evokes the characteristic changes in permselectivity and morphology, and the morphology is similar to idiopathic MCD.13 It is possible that similar or identical pathogenetic mechanisms are operative and a distinct etiologic link has been suggested to exist between the extraglomerular disease process and the occurrence of MCD.13 The linkage would strongly be indicated if the cure of extraglomerular disease leads to the eradication of MCD and if the recurrence of extraglomerular disorder is associated with relapse.13 We thoroughly examined her medical histories including medication uses. She had no other relevant medical history except for a ten-year history of hypertension, and she was not taking any other medications except for daily 10 mg of amlodipine. We found out that heavy proteinuria developed after using anti-tuberculosis agents. Fortunately, her proteinuria was improved after discontinuation of rifampicin and isoniazid. In addition, we added isoniazid except for rifampicin, but MCD did not recur. Taken together, the use of rifampicin seems to have resulted in developing MCD mostly in this case.

Although there are no definite mechanisms offered for rifampicin-induced MCD, a hypersensitivity mechanism has been suggested in many drug-induced MCD cases. For example, drug exposure can result in the release of permselectivity promoting factors from activated inflammatory or immune cells, causing MCD.13 Another possible mechanism of MCD is via direct toxin effects on glomerular epithelial cells, resulting in abnormal permeability and effacement of the foot processes.13 Neugarten, et al.7 reported the first case of rifampicin-induced nephrotic syndrome, and described the patient as having acute interstitial nephritis with heavy proteinuria and effacement of the glomerular epithelial cells. They suggested that cell-mediated and humoral immune responses to the rifampicin treatment could develop,7 and Tada, et al.9 suggested that endothelial injury resulting from rifampicin-induced hemolysis and thrombocytopenia seems to play a role in the development of nephrotic syndrome.9 In our case, there was no electron-dense glomerular deposits or immune complex glomerulonephritis to suggest a humoral immune mechanism.7 Additionally, there was no hemolysis or thrombocytopenia. Thus, we surmised that, rifampicin-induced MCD in this case, might have originated from direct toxin effects.

In many cases, withdrawal of the offending drugs can lead to a full recovery, and glucocorticoids may hasten the return of renal function and ameliorate proteinuria.13 In one rifampicin-induced MCD case, the MCD was improved after oral administration of prednisolone and the cessation of rifampicin.9 We simply terminated the rifampicin instead of initiating steroid therapy, and the patient recovered from heavy proteinuria, edema and hypoalbuminemia thereafter.

Although additional studies are required, simply discontinuing rifampicin may improve the rifampicin-induced MCD without the need for steroid therapy.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1(A) Light microscopy shows minor abnormalities of the glomeruli. The tubules show minimal atrophy and mild focal tubular injury. The interstitium is widened by minimal fibrosis. Non-sclerotic glomeruli are normocellular without mesangial expansion (H&E staining). (B) Electron microscopy shows diffusely effaced foot processes. The glomerular basement membranes are relatively even, but focal thinning of the lamina densa is noted. The mesangium is not expanded and is free of electron-dense deposits (H&E staining). |

References

1. Covic A, Goldsmith DJ, Segall L, Stoicescu C, Lungu S, Volovat C, et al. Rifampicin-induced acute renal failure: a series of 60 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998; 13:924–929.

2. De Vriese AS, Robbrecht DL, Vanholder RC, Vogelaers DP, Lameire NH. Rifampicin-associated acute renal failure: pathophysiologic, immunologic, and clinical features. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998; 31:108–115.

3. Gabow PA, Lacher JW, Neff TA. Tubulointerstitial and glomerular nephritis associated with rifampin. Report of a case. JAMA. 1976; 235:2517–2518.

4. Kohno K, Mizuta Y, Yoshida T, Watanabe H, Nishida H, Fukami K, et al. Minimal change nephrotic syndrome associated with rifampicin treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000; 15:1056–1059.

5. Murray AN, Cassidy MJ, Templecamp C. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis associated with rifampicin therapy for pulmonary tuberculosis. Nephron. 1987; 46:373–376.

6. Muthukumar T, Jayakumar M, Fernando EM, Muthusethupathi MA. Acute renal failure due to rifampicin: a study of 25 patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002; 40:690–696.

7. Neugarten J, Gallo GR, Baldwin DS. Rifampin-induced nephrotic syndrome and acute interstitial nephritis. Am J Nephrol. 1983; 3:38–42.

8. Rekha VV, Santha T, Jawahar MS. Rifampicin-induced renal toxicity during retreatment of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2005; 53:811–813.

9. Tada T, Ohara A, Nagai Y, Otani M, Ger YC, Kawamura S. A case report of nephrotic syndrome associated with rifampicin therapy. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 1995; 37:145–150.

10. Yoshioka K, Satake N, Kasamatsu Y, Nakamura Y, Shikata N. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis due to rifampicin therapy. Nephron. 2002; 90:116–118.

11. Black DA, Rose G, Brewer DB. Controlled trial of prednisone in adult patients with the nephrotic syndrome. Br Med J. 1970; 3:421–426.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download