Abstract

Purpose

Cigarette smoking is associated not only with increased risk of cancer incidence, but also influences prognosis, and the quality of life of the cancer survivors. Thus, smoking cessation after cancer diagnosis is necessary. However, smoking behavior among Korean cancer-survivors is yet unknown.

Materials and Methods

We investigated the smoking status of 23770 adults, aged 18 years or older, who participated in the Health Interview Survey of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2007 to 2010. Data on the cancer diagnosis and smoking history were obtained from an interview conducted by trained personals. "Cancer-survivor" was defined as anyone who has been diagnosed with cancer by a physician regardless of time duration since diagnosis. Smoking status was classified into "never-smoker", "former-smoker", and "current-smoker". Former-smoker was further divided into "cessation before diagnosis" and "cessation after diagnosis".

Results

Overall, 2.1% of Korean adults were cancer-survivors. The smoking rate of Korean cancer-survivors was lower than that of non-cancer controls (7.8±1.3% vs. 26.4±0.4%, p<0.001). However, 53.4% of the cancer-survivors continued to smoke after their cancer diagnosis. In multivariate analysis, male gender [odds ratio (OR), 6.34; 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.62-15.31], middle-aged group (OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.12-6.72), the lowest income (OR, 4.10; 95% CI, 1.19-14.15), living with smoking family member(s) (OR, 5.49; 95% CI, 2.42-12.48), and the poor self-perceived health status (OR, 2.78; 95% CI, 1.01-7.71) were independently associated with persistent smoking among Korean cancer-survivors.

Cigarette smoking is known to increase the risk for various types of cancers. It interferes with cancer treatment,1,2 increases the cancer mortality,3,4 and promotes the development of new primary cancers among cancer survivors.5 Nonetheless, western studies showed that more than 50% of the cancer survivors continue to smoke even after their cancer diagnosis.6,7

Due to early diagnosis and effective treatment of cancer, the prognosis of cancer patients has steadily been improving. Consequently, therefore, the proportion of cancer survivors has been increasing among the general population as well.8 However, data on the health-related behaviors of cancer survivors are limited, especially those related to smoking behavior.

Under the strong influence of "Confucianism" in East Asia, the smoking pattern of Koreans differs considerably from that of Westerners; Korean women have a low smoking rate of 6.2%, while Korean men have a high smoking rate of 42.1%.9 Thus, the smoking status in Korean cancer survivors may differ as well.

This study was to evaluate the smoking status of Korean cancer survivors and delineate factors that influence smoking status from a representative sample of Korean adults.

The KNHANES is a population-based, cross-sectional survey to assess the health-related behavior, the health condition, and the nutritional state of Koreans. It consists of the Health Interview Survey (HIS), the Nutrition Survey, and the Health Examination Survey. This study included 23770 adults, aged 18 years or older, who participated in the HIS from 2007 to 2010. The detailed descriptions of the plan and operation of the survey have been described on the KNHANES website (http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/).

Data on the cancer history were obtained via the HIS. The interview was performed by trained personals asking a specific question "Have you ever been diagnosed with cancer by a physician?" If the respondent concurred with the question, he or she was considered as a "cancer survivor" regardless of time duration since diagnosis, whereas those who denied were classified as "non-cancer control". Cancer survivors were further questioned on the type of cancer and the age at cancer diagnosis. In case of multiple cancer diagnoses, the latest one was used as an index cancer. We excluded cancer survivors who were diagnosed with cancer at the age of 18 or younger. Time duration since cancer diagnosis was estimated by subtracting the age at cancer diagnosis from the current age and categorized into "<2 years", "2 to <5 years", "5 to <10 years", and "more than 10 years". The type of cancer was classified into smoking-related and smoking-unrelated cancers. Smoking-related cancers included lung, mouth, lips, nasal cavity, and paranasal sinuses, larynx, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, kidney, bladder, uterine cervix, colon/rectum, ovary cancers, and acute myeloid leukemia.10

Smoking history was revealed by interviews. It included current smoking status, smoking cessation duration, and whether other smoker(s) existed in the household. Smoking status was classified into "never-smoker", "former-smoker", and "current-smoker". Individuals who reported to smoke less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were considered "never-smokers". Those who smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and stopped smoking prior to interview were considered "former-smokers". The former-smokers were further asked the time point of the smoking cessation. The time intervals between index cancer diagnosis and smoking cessation were calculated to check if the participants stopped smoking before or after cancer diagnosis. The "current-smokers" were further questioned on smoking amount and plans for smoking cessation.

We collected data on the demographic (age and marital status) and socioeconomic (household income and education) factors, and health perception (self-perceived health status).

Marital status was classified into "married" and "single". The household income level was classified into quartiles and education level into ≤9, 10-12, and ≥13 years of education. The self-reported perceived health status was categorized into "good", "moderate", and "poor".

Analytic sample included 23777 Koreans aged 18 years old or older, including 650 cancer survivors

Descriptive statistics of the demographic characteristics and smoking patterns were presented according to the cancer history. The differences in characteristics between cancer survivors and non-cancer controls were assessed using the logistic regression for categorical variable and the general linear modeling for continuous variable. Smoking rates were presented according to the cancer subtypes if there were more than 30 cases of cancer survival for a specific subtype.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the relationship between the smoking status and related factors after adjustment for covariates. The outcome variable was the smoking status. Factors known to affect the likelihood of being a persistent smoker were adjusted. Those factors were gender, age, education, household income level, marital status, self-perceived health status, years since cancer diagnosis, smoking household member, and cancer type (smoking-related or not). We additionally adjusted for the survey year.

All analyses were weighted to incorporate sampling weight considering the multistage probability sampling design of KNHANES and non-response with SPSS 18.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. IIT-2012-203). Informed consent was waived.

The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. In this representative population, 2.1% of the Korean adults were cancer survivors. Cancer survivors were older, more likely to be female, married, and less educated. They had lower income level than non-cancer controls (all p<0.001). As for the time interval since cancer diagnosis, 19.0% of the cancer survivors had a time interval of 2 years or less, 34.4% between 2 and 5 years, 23.0% between 5 and 10 years and 23.5% longer than 10 years ago.

Cancer survivors were less likely to be current smokers (7.8±1.3% vs. 26.4±0.4%), but more likely to be former smokers (29.2±2.3% vs. 19.5±0.3%) or never smokers (63.0±2.3% vs. 54.2±0.4%) than non-cancer controls (p<0.001) (Table 2). The difference in current smoking rate between cancer survivors and non-cancer controls was observed only among males (46.3±0.6% vs. 14.5±2.9%, p<0.001), but not among females (6.5±0.3% vs. 4.2±1.3%, p=0.144). Among the cancer survivors, 14.6% reported being current-smokers at the time of cancer diagnosis. Interestingly, 53.4% among them continued to smoke even after their cancer diagnosis. Only one fourth of the current smokers planned to quit smoking within 6 months.

Stratifying the smoking status according to gender and age, in males the current smoking rates in cancer survivor groups were lower than non-cancer control group throughout all age groups (Fig. 1A). In contrast, in females the smoking rate of cancer survivors in middle-aged group (age between 45-64 years) was not different from that of non-cancer controls (5.8±2.7 vs. 4.7±0.4, p=0.603) (Fig. 1B).

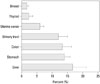

Fig. 2 shows the smoking rate of the survivors with cancer types that have 30 and more cases. Liver cancer survivors had the highest smoking rate (16.7%), followed by stomach cancer (14.0%), colon cancer (13.3%), and cancer of the urinary tract (12.1%). The smoking rate was 9.8% in survivors of smoking-related cancers, whereas the smoking rate was only 4.0% in those of smoking-unrelated cancer (Table 3).

As for the risk factor for persistent-smoking among the cancer survivors, male gender [odds ratio (OR), 6.34; 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.62-15.31], middle-aged group (OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.12-6.72), the low income (lowest income: OR, 4.10; 95% CI, 1.19-14.15), living with smoking family members (OR, 5.49; 95% CI, 2.42-12.48), and the poor self-perceived health status (OR, 2.78; 95% CI, 1.01-7.71) were associated independently with persistent smoking in Korean cancer survivors (Table 3).

In this representative population-based study, we showed that only 7.8% of cancer survivors were current smokers in Korea, which is remarkably lower than the rate in Western studies-ranging from 15% to 32%.11,12,13,14 The difference may be explained by the demographic factors: two thirds of Korean adult cancer survivors were women, whose smoking rate (6.2%) was only one eighth of that of Korean men (42.1%). Under the strong influence of "Confucianism", women's smoking is regarded as "socially unacceptable" in Korea.

We showed that male gender, middle age, lowest household income, living with smoking family members, and poor health self-perception were associated independently with the persistent smoking among the cancer survivors. This result is in line with Western studies.15,16,17 Among the risk factors, the male gender and the living with smoking family members were strong risk factors. Concerning the male gender, it was associated with six-fold increased risk for persistent smoking (OR, 6.34; 95% CI, 2.62-15.31). Living with a smoking family member was associated with five-fold increased odd (OR, 5.49; 95% CI, 2.42-12.48) of persistent smoking.7,18 Smoking family members significantly lower the motivation to quit smoking.7 Thus, it is essential to involve family members for successful smoking cessation among the cancer survivors.19

The smoking rate of cancer survivors varies with cancer type. We showed that smoking-related cancer survivors had a higher smoking rate than that of smoking-unrelated cancer survivors (9.8% vs. 4.0%, p=0.080) with a marginal significance, exposing smoking-related cancer survivors to increased risks for the development of secondary cancers. In particular, the smoking rate of cervical cancer-a smoking-related cancer-survivors was three times higher than that of breast cancer-a smoking-unrelated cancer-(5.9% vs. 1.8%) in our study population, as was in the US National Health Interview Survey (46% vs. 14.1%),20 suggesting that some of the health behaviors promoting cancer development persist still after cancer diagnosis.

Smoking cessation after cancer diagnosis increases survival rate and the quality of life,21 decreases the development of a secondary malignancy, and relieves psychological distress.14 Despite many beneficial effects of smoking cessation, less than 50% of patients quit smoking after cancer diagnosis in this study. Western studies reported that the smoking cessation rate after cancer diagnosis ranged between 22-69%.7 Strikingly, 50% of ex-smokers reported to restart cigarette smoking,22 suggesting a high addictive potential of cigarette smoking and the need for comprehensive and systematic prevention programs for smoking cessation.

The optimal timing for such intervention may be as soon as after cancer diagnosis,6 when the patients are highly motivated to improve their health-related behavior.23 Thus, healthcare providers, especially those involved in the initial cancer treatment, should take a primary role in counseling patients and encouraging smoking cessation. Furthermore, smoking cessation programs should be accessible to all patient groups regardless of socioeconomic status. Currently, smoking cessation therapy is not reimbursed by the National Health Insurance in Korea, necessitating changes in the national health policy.

There are several limitations in this study. First, KNHANES is not designed to elucidate the reasons why cancer survivors continue smoking after cancer diagnosis. Second, the data on smoking history were self-reported. Underreporting of smoking history is common among patients.24 Third, although adjusted for significant clinical variables in Korean adults, there could be residual or unmeasured confounders which may influence smoking behavior.

In conclusion, Korean cancer survivors have lower smoking rate than Western counterparts. However, despite hazardous effect of cigarette smoking, more than half of the patients continue smoking after cancer diagnosis, and especially male gender, middle-aged group, the low income level, living with smoking family members, and the poor perceived health status are risk factors for the persistent smoking. The high cigarette smoking rate after diagnosis mandates comprehensive and systematic intervention for smoking cessation among cancer survivors.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Percentage of current smokers among cancer survivors and remaining Korean population by age, 2007-2010. (A) Male. (B) Female. |

| Fig. 2Cancer site specific smoking rate among Korean cancer survivors, 2007-2010. Only cancer types which had more than 30 cases of prevalence among cancer survivors were presented. |

Table 1

General Characteristics of Study Population

Table 2

Smoking Status of Cancer Survivors and Non-Cancer Controls

Table 3

Odds of Being Current Smoker among Cancer Survivors

OR, odds ratio; SE, standard error.

*OR and trend P were based on multiple logistic regression analysis, controlling all other characteristics included in the table and the survey year.

†Smoking related cancer included lung, mouth, lips, nasal cavity, and paranasal sinuses, larynx, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, kidney, bladder, uterine cervix, colon/rectum, ovary cancers, and acute myeloid leukemia.10

References

1. Gritz ER, Dresler C, Sarna L. Smoking, the missing drug interaction in clinical trials: ignoring the obvious. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005; 14:2287–2293.

2. Browman GP, Wong G, Hodson I, Sathya J, Russell R, McAlpine L, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:159–163.

3. Johnston-Early A, Cohen MH, Minna JD, Paxton LM, Fossieck BE Jr, Ihde DC, et al. Smoking abstinence and small cell lung cancer survival. An association. JAMA. 1980; 244:2175–2179.

4. Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, Aveyard P. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010; 340:b5569.

5. Do KA, Johnson MM, Doherty DA, Lee JJ, Wu XF, Dong Q, et al. Second primary tumors in patients with upper aerodigestive tract cancers: joint effects of smoking and alcohol (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2003; 14:131–138.

6. Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Mehta NV, Reece GP. Successes and failures of the teachable moment: smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer. 2006; 106:17–27.

7. Burke L, Miller LA, Saad A, Abraham J. Smoking behaviors among cancer survivors: an observational clinical study. J Oncol Pract. 2009; 5:6–9.

8. Ministry of Health and Welfare, National Cancer Center. Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare, National Cancer Center;2013. Available at: http://ncc.re.kr/pr/issue_list.jsp?schisgubun=A&selSearch=null&txtKeyword=¤t_page=2.

9. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Korea Health Statistics 2013: Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI-I). 2014. Available at: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/index.do.

10. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. Atlanta: American Cancer Society;2012.

11. Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Stewart SL, Buchannan N, Ekwueme DU, Hawkins NA, et al. Surveillance of demographic characteristics and health behaviors among adult cancer survivors--Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012; 61:1–23.

12. Tseng TS, Lin HY, Moody-Thomas S, Martin M, Chen T. Who tended to continue smoking after cancer diagnosis: the national health and nutrition examination survey 1999-2008. BMC Public Health. 2012; 12:784.

13. Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23:8884–8893.

14. Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003; 58:82–91.

15. Emmons KM, Butterfield RM, Puleo E, Park ER, Mertens A, Gritz ER, et al. Smoking among participants in the childhood cancer survivors cohort: the Partnership for Health Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003; 21:189–196.

16. Schnoll RA, Malstrom M, James C, Rothman RL, Miller SM, Ridge JA, et al. Correlates of tobacco use among smokers and recent quitters diagnosed with cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2002; 46:137–145.

17. Schnoll RA, Engstrom PF, Subramanian S, Demidov L, Wielt DB, Tighiouart M. Prevalence and correlates of tobacco use among Russian cancer patients: implications for the development of smoking cessation interventions at a cancer center in Russia. Int J Behav Med. 2006; 13:16–25.

18. Kahalley LS, Robinson LA, Tyc VL, Hudson MM, Leisenring W, Stratton K, et al. Risk factors for smoking among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012; 58:428–434.

19. de Moor JS, Elder K, Emmons KM. Smoking prevention and cessation interventions for cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008; 24:180–192.

20. Coups EJ, Ostroff JS. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev Med. 2005; 40:702–711.

21. Garces YI, Yang P, Parkinson J, Zhao X, Wampfler JA, Ebbert JO, et al. The relationship between cigarette smoking and quality of life after lung cancer diagnosis. Chest. 2004; 126:1733–1741.

22. Demark-Wahnefried W, Pinto BM, Gritz ER. Promoting health and physical function among cancer survivors: potential for prevention and questions that remain. J Clin Oncol. 2006; 24:5125–5131.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download