Abstract

Purpose

Increased awareness and understanding of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an important aspect of disease management. The aim of this study was to explore COPD awareness among smokers participating in a smoking cessation program.

Materials and Methods

Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 289 subjects in three smoking cessation clinics, using a structured questionnaire.

Results

A total of 68.2% of subjects had COPD-related symptoms, and 19.7% were in poor health. Only 1.0% of the subjects knew that COPD was a respiratory disease. A total of 2.4% of subjects had been diagnosed with COPD and received treatment. Television was the most common source of information about COPD, with 57.1% of the subjects receiving information in this way. After being informed about COPD, smoking-cessation willingness increased in 84.1% of the study group. It increased in 86.3% of the subjects without awareness of COPD and in 81.2% of subjects with COPD-related symptoms.

Conclusion

We found that awareness of COPD is very poor among current smokers in Korea. Many smokers perceived their health status as good, despite the presence of COPD-related symptoms. As the level of smoking-cessation willingness was different between those with and without awareness of COPD or COPD-related symptoms, a personalized education program with various educational tools may be needed to enhance awareness of the disease and to motivate smokers to quit.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major contributor to global mortality and morbidity. In Korea, the prevalence of COPD is 12.9%, and COPD is the sixth leading cause of death.1,2 COPD has a negative impact not only on patients but also on family members who have to take care of them.3 In 2010, COPD accounted for 2.8 billion US dollars in direct medical expenses in Korea.4 Therefore, the medical, social, and economic burdens of COPD are extremely substantial.

Cigarette smoking is the most common risk factor for COPD. Smokers have a higher prevalence of respiratory symptoms and lung function abnormalities and a greater mortality rate than nonsmokers.5 The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease consensus report was developed to provide a more uniform set of recommendations for the diagnosis and management of COPD and to increase awareness and understanding of this condition among patients and the public.5 Public awareness of COPD is poor, due to the disease receiving less media attention than other common chronic diseases, such as asthma or diabetes.6 The lack of awareness of COPD means that the disease is substantially underdiagnosed and typically missed or delayed until the condition is advanced.6,7 According to one study, only 2.5% of subjects in Korea with airflow limitation confirmed by spirometry were treated for COPD.1 In addition to preventing timely diagnosis of the disease, the absence of awareness impedes implementation of optimal standards of care and appropriate prevention strategies.6

We previously examined COPD awareness among those with the disease.8 However, no studies have investigated the attitudes of smokers to COPD among those who are at risk of developing the disease in Korea. We present the results of a survey of the attitudes to COPD held by smokers participating in a smoking-cessation program.

This study was a cross-sectional survey in three smoking cessation clinics, which were operated by a regional public health center. The clinics provide smoking cessation education, counseling, and nicotine replacement therapy free of charge. Eligible subjects were current smokers aged 45 years and older with a history of at least 10 pack-years of smoking. They were randomly selected, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. An experienced interviewer conducted face-to-face interviews with the participants. This study was approved by the Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital Institutional Review Board (HUSSS IRB No.2014-I007).

A structured questionnaire was used to collect data on each participant's current health status, symptoms, awareness of COPD, and attitudes to COPD after learning about or being diagnosed with the disease. The average time to complete the full questionnaire was 20 min.

In addition to a basic demographics section, the questionnaire included additional sections on the following: the first section focused on the subject's current health status and symptoms. The second section addressed awareness of smoking-related respiratory disease. The third section was on the diagnosis of COPD by a physician or COPD treatment. The fourth section focused on attitudes to COPD after being informed about the disease. The final section dealt with the subject's willingness to receive treatment for COPD. Descriptive statistics [e.g., frequency and mean±standard deviation (SD)] were calculated for all qualitative and quantitative variables.

A total of 289 subjects were enrolled in this survey, with a male predominance (94.5%). The age distribution was as follows: 45-49 (29.4%), 50-59 (41.2%), 60-69 (24.2%), and 70 or older (5.2%). A total of 46.7% of subjects had been smoking for 30-39 years (Table 1)

A total of 36.0% of the subjects said they were in good health, and 19.7% said they had poor health. Participants who had smoked for a longer time as well as those with COPD-related symptoms or a history of asthma tended to have a poor health status. The proportion of subjects with a good health status was higher in 1-pack/day smokers than in those who smoked more packs per day (Table 2).

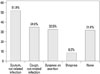

The subjects were questioned about the presence or absence of COPD-related symptoms, such as cough or sputum, irrespective of upper respiratory infection, dyspnea on exertion (DOE) equivalent to mMRC 2 or higher, and resting dyspnea. A relatively high number of subjects (68.2%) had at least one COPD-related symptom. The most common symptom was sputum (51.9%), followed by cough (34.9%) and DOE (32.5%) (Fig. 1). Among the participants, 65.1% of those who had smoked for longer than 40 years had sputum, and 70% of those who had more than a 2-pack/day history experienced DOE. The mean durations of the symptoms were as follows: 4.94 years for cough, 4.24 years for sputum, 4.94 years for DOE, and 2.47 years for resting dyspnea. However, 41.6% of the subjects with symptoms did not seek medical advice. A total of 24.4% of symptomatic subjects went to see a doctor.

COPD awareness was evaluated in two ways. First, the subjects were asked to name three respiratory diseases. Lung cancer was the most common response (58.1%). Only 1.0% of the subjects named COPD as a respiratory disease (Fig. 2). Second, the subjects were directly asked if they knew what COPD was. A total of 21.8% of the subjects answered that they knew that COPD was a respiratory disease. Awareness of COPD did not differ according to demographic characteristics (Table 3). Among the subjects with COPD-related symptoms, only 21.8% knew that COPD was a respiratory disease. When subjects were asked about the cause of COPD, 91.3% responded that smoking was responsible.

Among the various routes for obtaining information about COPD, such as television, family and friends, newspapers, doctors, radio, and the Internet, television was the most common (57.1% of participants). Only 15.7% of the study subjects obtained information about COPD from doctors.

Among the subjects enrolled in this study, only 2.4% had been diagnosed with COPD or treated for the disease. When the subjects without COPD were asked what they would do first if they developed COPD, only 66.7% said they would see a doctor to seek medical advice about treatment.

Analysis of smoking-cessation willingness showed that it increased in 84.1% of the subjects after they were informed about COPD. Smoking-cessation willingness differed depending on awareness of COPD or the presence of COPD-related symptoms. It increased more among those who were not aware of the disease prior to the program (86.3%) than among those who were already aware of the disease (76.2%). Smoking-cessation willingness increased in 81.2% of the subjects with COPD-related symptoms (Table 4).

In this study, we found that 68.2% of smokers had COPD-related symptoms, and 19.7% were in poor health. Although the duration of COPD-related symptoms (except for resting dyspnea) was at least 4 years in all subjects, 41.6% of symptomatic subjects did not do anything about their symptoms, such as quitting smoking or visiting a clinic. This suggests that a number of smokers have a positive perception of their health status, despite the presence of respiratory symptoms. This finding is consistent with previous findings that only 50.3% of COPD patients accepted that smoking was responsible for their respiratory symptoms6 and that COPD patients adapted their lifestyle to compensate for their deteriorating health.9

In addition, most of the subjects (99%) in the current study did not name COPD as a respiratory disease. The 1% of subjects who were aware that COPD was a respiratory disease is much lower than the 17.0% figure reported in the CONOCEPOC study conducted in Spain.10 A total of 21.8% of the participants knew that COPD was a respiratory disease, and awareness of COPD was the same among subjects with and without COPD-related symptoms. Furthermore, only 2.4% of current smokers had been diagnosed with COPD and received treatment, a figure that is comparable with that of the general population in Korea.1 The findings indicate that COPD is underdiagnosed and undertreated, even in current smokers who are willing to quit smoking. They also reveal that awareness of COPD is very poor in smokers, highlighting the need to increase public awareness of the diagnosis and treatment of COPD in this population.

Airflow limitation, which is a characteristic feature of COPD, is usually progressive. Current medications for COPD cannot change the natural course of the disease. Such change can only be achieved by smoking cessation, which is also necessary to reduce related mortality.5 A previous study reported that patients who had little knowledge of COPD were more likely to have poor adherence to treatment.11 Therefore, patient education is an important aspect of COPD management. The most important aspects of education are providing basic information on COPD and advice on smoking cessation.5 As reported previously, quitting smoking before the age of 40 years compared with continuing smoking reduces the risk of death by about 90%.12 Therefore, improving awareness of the consequences of smoking for respiratory health is important, and smoking cessation advice should be offered repeatedly in patients with early COPD.7 In this study, 91.3% of subjects responded that smoking was the cause of COPD, and 84.1% responded that their willingness to quit smoking increased after being informed about COPD. This increase in the willingness to give up smoking may be exaggerated in this study, as all the subjects had already participated in a smoking cessation program. However, it could also indicate that the willingness to quit smoking could increase dramatically through education on COPD. A new study targeting smokers who had not participated in a smoking cessation program previously is warranted to clarify the role of enhanced awareness of COPD in the motivation to quit.

On the other hand, 5.5% of the study subjects responded that their smoking-cessation willingness decreased after being informed about COPD, and 8.7% showed no change in smoking-cessation willingness. The proportion of smokers who were less willing to quit smoking was higher among those who were aware of COPD or who had COPD-related symptoms. As only one-half of COPD patients accepted that smoking was responsible for their respiratory illness,6 stereotypical education about COPD may be ineffective in some smokers. Instead, a personalized education program may be needed to enhance awareness of COPD and motivate subjects to quit smoking.13 In the current study, only 66.7% of subjects said they would seek medical help if they developed COPD. Thus, undertreatment continues to be a problem in COPD management, despite early detection of the disease. Enhancing awareness of COPD may be helpful in addressing this problem.

In this study, a large number of subjects (57.1%) acquired information about COPD from television, whereas only a small number (15.9%) obtained information on the disease from doctors. These figures are quite different from those reported in the BREATHE study,6 which reported that two-thirds of subjects were informed by physicians and 10.1% claimed to obtain information from television. One study conducted in Korea previously clarified that the most frequently utilized health information source was mass media. 14 Therefore, it is possible that the discrepancy from BREATHE study was caused by the cultural difference reflected in the more powerful effects of mass media in Korea. Additionally, in the current study, 68.2% of subjects also said that television was the most reliable source of information about COPD treatment. This finding is consistent with the previous study, which found that mass media was the most understandable (35.2%) and the second-most reliable (22.9%) information source.14 As mentioned above, television is a powerful information source in Korea; therefore, health care providers should widely use this medium for COPD education or campaigns.

Another study reported that 88% of COPD patients in Korea felt that they had received sufficient information about the disease from doctors; however, only 57.7% of these patients knew the exact diagnosis of their medical condition.8 The gap between what patients felt they knew and what they actually knew may come from the paternalistic culture and one-way communication from doctors to patients in Korea. These results indicate that new educational strategies are needed to deliver accurate information on COPD to the general population. For example, given that people who are accustomed to the Internet will automatically use this medium to search for information about diseases,9 it may be a useful resource for COPD education.

There are several limitations in our study. First, we excluded subjects younger than 45 years, as COPD is a disease that affects older individuals. To assess public awareness of COPD, studies are needed that include young smokers. Second, we classified subjects into only two groups according to education level: high-school level or less and college level or more. Awareness of COPD was not different between these education-based groups; however, stratifying the subjects into additional groups based on educational level might have shown an effect of education on awareness of COPD. However, as only about one-fifth of the subjects in each education-based group knew about COPD, efforts to increase awareness of the disease should target people of all educational levels.

In conclusion, we found that awareness of COPD was very poor in current smokers in Korea. Many smokers perceived their health status as good, despite the presence of COPD-related symptoms. In addition, smokers thought that television was a better source of information about COPD than physicians. Smoking-cessation willingness increased after being informed about COPD; however, the level of increased smoking-cessation willingness differed between the subjects with or without awareness of COPD or COPD-related symptoms. Therefore, initiatives other than patient education in the clinic are required to enhance public awareness. A personalized education program with various educational tools should be implemented to improve awareness of COPD and smoking-cessation willingness. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore awareness of COPD among smokers in Korea. The results of this study could provide basic data for developing a policy to increase public awareness of the disease in Korea.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Smokers' first impressions of lung or respiratory diseases. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of Study Subjects

Table 2

Self-Awareness of Health Status

Table 3

Proportion of Subjects Aware of COPD According to Demographic Characteristics

References

1. Yoo KH, Kim YS, Sheen SS, Park JH, Hwang YI, Kim SH, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008. Respirology. 2011; 16:659–665.

2. Korean Statistical Information Service (KSIS). The cause of death statistics. Available at: http://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsList_03List.jsp?vwcd=MT_RTITLE&parmTabId=M_03_01#SubCon.

3. Kim JH, Kim EK, Park SH, Lee KA, Hwang YI, Kim EJ, et al. Burden of COPD among Family Caregivers. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2010; 69:434–441.

4. Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. 2009. accessed on 2010 June 1. Available at: http://www.hira.or.kr.

5. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. update 2014. Available at: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.html.

6. Sayiner A, Alzaabi A, Obeidat NM, Nejjari C, Beji M, Uzaslan E, et al. Attitudes and beliefs about COPD: data from the BREATHE study. Respir Med. 2012; 106:Suppl 2. S60–S74.

7. Soriano JB, Zielinski J, Price D. Screening for and early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2009; 374:721–732.

8. Hwang YI, Kwon OJ, Kim YW, Kim YS, Park YB, Lee MG, et al. Awareness and Impact of COPD in Korea: An Epidemiologic Insight Survey. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2011; 71:400–407.

9. Fromer L. Diagnosing and treating COPD: understanding the challenges and finding solutions. Int J Gen Med. 2011; 4:729–739.

10. Soriano JB, Calle M, Montemayor T, Alvarez-Sala JL, Ruiz-Manzano J, Miravitlles M. The general public's knowledge of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinants: current situation and recent changes. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012; 48:308–315.

11. Khdour MR, Hawwa AF, Kidney JC, Smyth BM, McElnay JC. Potential risk factors for medication non-adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012; 68:1365–1373.

12. Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostron B, Thun M, Anderson RN, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:341–350.

13. Fiore MC, Baker TB. Clinical practice. Treating smokers in the health care setting. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:1222–1231.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download