Abstract

We report a case of regression of multiple pulmonary metastases, which originated from hepatocellular carcinoma after treatment with intravenous administration of high-dose vitamin C. A 74-year-old woman presented to the clinic for her cancer-related symptoms such as general weakness and anorexia. After undergoing initial transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), local recurrence with multiple pulmonary metastases was found. She refused further conventional therapy, including sorafenib tosylate (Nexavar). She did receive high doses of vitamin C (70 g), which were administered into a peripheral vein twice a week for 10 months, and multiple pulmonary metastases were observed to have completely regressed. She then underwent subsequent TACE, resulting in remission of her primary hepatocellular carcinoma.

Ascorbate (vitamin C) is a fundamental vitamin for human life as an important antioxidant by blocking damage from free radicals,1 and acts as a cofactor for hydroxyl enzymes in collagen synthesis which has been thought to prevent tumor spreading.23 On the other hand, high-dose vitamin C can act as a prooxidant, conferring selective toxic effects on cancer cells.4 Also, it may exert anti-inflammatory activity resulting in suppression of tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis.5 High-dose vitamin C supplementation has been widely used as complementary and alternative medicine, particularly in cancer patients.6 Although there is a paucity of clinical research data to confirm the effects of vitamin C on cancer, some interesting case reports have suggested the clinical prospect of high-dose vitamin C therapy.78 One of these is similar to our report, except it involved multiple pulmonary metastases originating from renal cell cancer.8 Here, we report a case of regression of multiple pulmonary metastases originating from hepatocellular carcinoma after high-dose vitamin C therapy.

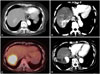

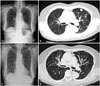

A 74-year-old woman was found to have a 2.2-cm liver mass with multiple satellite nodules (T2N0M0) on abdominal-pelvic CT (APCT) in January 2011 (Fig. 1A). Protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA II) was within normal range, 28 mAU/mL, but alpha fetoprotein (AFP), 4040.05 ng/mL, was high, and anti-hepatitis C virus was positive. The patient initially received transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in February 2011, but locally recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma with multiple pulmonary and mediastinal lymph node metastases were found on positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) scan in July 2011 (Fig. 2A and B) and APCT in September 2011 (Fig. 1B). She refused further treatment, including sorafenib tosylate (Nexavar, Bayer Health-Care AG, Leverkusen, Germany), and then visited our clinic with anorexia and general weakness in September 2011 requesting high-dose vitamin C to manage her symptoms. Twenty grams of vitamin C in 250 mL normal saline was initially administered via an ante-cubital vein twice a week in September 2011 after urine analysis and renal function were confirmed to be within normal range. To neutralize acidic pH (3.5-5.0) of vitamin C, it was mixed with NaHCO3, resulting in pH 6.2 (UniC®, 500 mg/mL from Unimed Pharmaceuticals, Seoul, Korea). In addition, normal saline was changed to distilled water as vitamin C dose increased to avoid too much intake of volume and sodium and too high concentration. Furthermore, magnesium sulfate 1 g was blended in the fluid to prevent vascular irritation.9 Notably, she did not have glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Prior to April 2012, no significant progression or regression of her multiple pulmonary metastases was found on serial chest X-ray, although she reported improved general wellbeing. In July 2012, multiple pulmonary nodules were found to have completely regressed on chest X-ray (Fig. 2C), which was confirmed on PET-CT scan in September 2012 (Fig. 2D). However, a 5.5-cm hepatic mass still remained on abdomen ultrasound and PET-CT scan (Fig. 1C). Considering her good performance status, we recommended repeated TACE, but she declined. Therefore, high-dose vitamin C administration was continued for more than a year. In July 2013, she finally decided to undergo TACE in addition to the high-dose vitamin C treatment. Subsequently, three rounds of TACE were performed. After the fourth round of TACE, the hepatic mass was found to have entirely regressed (Fig. 1D), and both PIVKA II and AFP levels had returned to normal range. The serial changes in AFP and PIVKA II levels are shown in Table 1. The patient denied any use of other anti-cancer medications or alternative therapies except pain medication for her intermittent abdominal pain. She was quite tolerant of high-dose vitamin C during the entire treatment period, but thirst was an occasional complaint, which was easily remedied by water intake.

In the 1970s, Cameron and Pauling reported that high-dose vitamin C had therapeutic effects in cancer.10 Early clinical studies showed that high-dose vitamin C administration conferred survival benefit compared to control groups.1112 However, a subsequent clinical study at Mayo Clinic failed to show significant differences in survival between an oral vitamin C administration group and the control group.13 In addition to these studies in which oral vitamin C was tested, a recent pharmacokinetic study suggests that high concentrations of intravenous vitamin C are toxic to cancer cells.14 Hoffer, et al.15 reported that when 1.5 g/kg of vitamin C was administered, plasma concentrations over 10 mM could be maintained for 4.5 hours. Some authors suggest that the oral administration of vitamin C at the Mayo Clinic could have failed to achieve effective plasma concentrations, and that effective concentrations can only be reached by intravenous administration.16 Therefore, further clinical studies to evaluate the anti-cancer effects of intravenous high-dose vitamin C are warranted.

Potential mechanisms of action of vitamin C on cancer cells remains uncertain, but recent experimental data suggest some possible mechanisms. First, vitamin C has a pro-oxidant effect at higher concentrations. Chen, et al.17 reported that high-dose vitamin C generated hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the extracellular fluid, which then entered into cells. H2O2 is able to accelerate the production of additional reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as aldehydes. These ROS are capable of several effects, including DNA damage, cell membrane dysfunction, and cellular adenosine triphosphate depletion in cancer cells due to reduced levels of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase. These processes are not found in normal cells and may lead to death of cancer cells.1819 Second, vitamin C may modulate inflammation resulting in increase of host resistance to cancer. Cho, et al.20 demonstrated that highly concentrated vitamin C decreased the production of interleukin-18, which is related to tumor cell growth, proliferation, and migration. Chen, et al.21 reported that the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α protein, which is associated with tumor growth, is inhibited by vitamin C in an animal study. In addition, Mikirova, et al.22 demonstrated that C-reactive protein level which is correlated with disease activity was reduced after high-dose vitamin C treatment in cancer patients.

In conclusion, we describe a case of regression of multiple pulmonary metastases after treatment with high-dose vitamin C, which enabled a subsequent trial of TACE, eventually leading to complete remission of the primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Notably, intravenous vitamin C administration has an advantage in terms of safety compared to other conventional cancer therapies. Our patient did not show any complications or serious side effects, except for mild thirst. Although there is controversy over the effect of vitamin C on cancer, intravenous administration of high-dose vitamin C could be attempted in patients who refuse conventional therapy. Also, we hope to find a common denominator in accumulated case reports that might offer clues to which cases vitamin C administration could be an effective cancer therapy.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Serial abdominal CT scan. (A) A 2.2-cm mass is shown in S7 of the liver (initial diagnosis, Jan-29-2011). (B) Recurrence of the tumor was shown in a previous TACE-treated lesion (Sep-05-2011). (C) Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma remained visible on PET-CT scan after the regression of multiple lung metastases with vitamin C administration (Sep-13-2012). (D) Hepatocellular carcinoma regressed completely after the fourth TACE treatment (Jan-28-2014). TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; PET-CT, positron emission tomography-computed tomography.

Fig. 2

Multiple well-defined nodules are evident in both lung fields on chest radiography (A) and chest CT scan (B) in September 2011, before the initiation of intravenous high-dose vitamin C treatment. Chest radiography in July 2012 (C) and chest CT in February 2013 (D) showing regression of the lesions.

Table 1

Serial Tumor Markers

References

1. Padayatty SJ, Katz A, Wang Y, Eck P, Kwon O, Lee JH, et al. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease prevention. J Am Coll Nutr. 2003; 22:18–35.

2. Levine M. New concepts in the biology and biochemistry of ascorbic acid. N Engl J Med. 1986; 314:892–902.

3. Bei R, Palumbo C, Masuelli L, Turriziani M, Frajese GV, Volti GL, et al. Impaired expression and function of cancer-related enzymes by anthocyans: an update. Curr Enzym Inhib. 2012; 8:2–21.

4. Bram S, Froussard P, Guichard M, Jasmin C, Augery Y, Sinoussi-Barre F, et al. Vitamin C preferential toxicity for malignant melanoma cells. Nature. 1980; 284:629–631.

5. Grosso G, Bei R, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Calabrese G, Masuelli L, et al. Effects of vitamin C on health: a review of evidence. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2013; 18:1017–1029.

6. Padayatty SJ, Sun AY, Chen Q, Espey MG, Drisko J, Levine M. Vitamin C: intravenous use by complementary and alternative medicine practitioners and adverse effects. PLoS One. 2010; 5:e11414.

7. Campbell A, Jack T, Cameron E. Reticulum cell sarcoma: two complete 'spontaneous' regressions, in response to high-dose ascorbic acid therapy. A report on subsequent progress. Oncology. 1991; 48:495–497.

8. Padayatty SJ, Riordan HD, Hewitt SM, Katz A, Hoffer LJ, Levine M. Intravenously administered vitamin C as cancer therapy: three cases. CMAJ. 2006; 174:937–942.

9. Riordan HD, Hunninghake RB, Riordan NH, Jackson JJ, Meng X, Taylor P, et al. Intravenous ascorbic acid: protocol for its application and use. P R Health Sci J. 2003; 22:287–290.

10. Cameron E, Campbell A. The orthomolecular treatment of cancer. II. Clinical trial of high-dose ascorbic acid supplements in advanced human cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 1974; 9:285–315.

11. Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: reevaluation of prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978; 75:4538–4542.

12. Cameron E, Campbell A. Innovation vs. quality control: an 'unpublishable' clinical trial of supplemental ascorbate in incurable cancer. Med Hypotheses. 1991; 36:185–189.

13. Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Creagan ET, Rubin J, O'Connell MJ, Ames MM. High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison. N Engl J Med. 1985; 312:137–141.

14. Padayatty SJ, Sun H, Wang Y, Riordan HD, Hewitt SM, Katz A, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann Intern Med. 2004; 140:533–537.

15. Hoffer LJ, Levine M, Assouline S, Melnychuk D, Padayatty SJ, Rosadiuk K, et al. Phase I clinical trial of i.v. ascorbic acid in advanced malignancy. Ann Oncol. 2008; 19:1969–1974.

16. González MJ, Miranda-Massari JR, Mora EM, Guzmán A, Riordan NH, Riordan HD, et al. Orthomolecular oncology review: ascorbic acid and cancer 25 years later. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005; 4:32–44.

17. Chen Q, Espey MG, Sun AY, Lee JH, Krishna MC, Shacter E, et al. Ascorbate in pharmacologic concentrations selectively generates ascorbate radical and hydrogen peroxide in extracellular fluid in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007; 104:8749–8754.

18. Gonzalez MJ. Lipid peroxidation and tumor growth: an inverse relationship. Med Hypotheses. 1992; 38:106–110.

19. Sun Y, Oberley LW, Oberley TD, Elwell JH, Sierra-Rivera E. Lowered antioxidant enzymes in spontaneously transformed embryonic mouse liver cells in culture. Carcinogenesis. 1993; 14:1457–1463.

20. Cho D, Hahm E, Kang JS, Kim YI, Yang Y, Park JH, et al. Vitamin C downregulates interleukin-18 production by increasing reactive oxygen intermediate and mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling in B16F10 murine melanoma cells. Melanoma Res. 2003; 13:549–554.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download