Abstract

Purpose

The purposes of this study were to evaluate specific dysphagia patterns and to identify the factors affecting dysphagia, especially aspiration, following treatment of head and neck cancer.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of 57 patients was performed. Dysphagia was evaluated using a modified barium swallow (MBS) test. The MBS results were rated on the 8-point penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) and swallowing performance status (SPS) score.

Results

Reduced base of the tongue (BOT) retraction (64.9%), reduced laryngeal elevation (57.9%), and cricopharyngeus (CP) dysfunction (47.4%) were found. Reduced BOT retraction was correlated with clinical stage (p=0.011) and treatment modality (p=0.001). Aspiration in 42.1% and penetration in 33.3% of patients were observed. Twenty-four patients had PAS values over 6, implying aspiration. Forty-one patients had a SPS score of more than 3, 25 patients had a score greater than 5, and 13 patients had a SPS score of more than 7. Aspiration was found more often in patients with penetration (p=0.002) and in older patients (p=0.026). In older patients, abnormal swallowing caused aspiration even in those with a SPS score of more than 3, irrespective of stage or treatment, contrary to younger patients. Tube feeders (n=20) exhibited older age (65.0%), dysphagia/aspiration related structures (DARS) primaries (75.0%), higher stage disease (66.7%), and a history of radiotherapy (68.8%).

Conclusion

Reduced BOT retraction was the most common dysphagia pattern and was correlated with clinical stage and treatment regimens including radiotherapy. Aspiration was more frequent in patients who had penetration and in older patients. In contrast to younger patients, older patients showed greater risk of aspiration even with a single abnormal swallowing irrespective of stage or treatment.

The primary treatment modalities for head and neck cancer (HNC) include surgery and radiotherapy, with an increasing role for chemotherapy and targeted molecular therapies. Treatment has intensified to improve local tumor control and survival rates. Unfortunately, these aggressive treatments can result in swallowing dysfunction. Silent aspiration and pneumonia were reported in 17 to 81% of patients with stage III and IV HNC. Additionally, long-term tube feeding was reported in as many as 30% of patients.12 Dysphagia and aspiration are long-term complications with life threatening consequences following treatment of HNC. Swallowing problems have a multifactorial and complex etiology, and current insight into the prevalence of swallowing dysfunction in HNC patients is still limited.

The purposes of this study were to evaluate specific dysphagia patterns by using a modified barium swallow (MBS) test and to identify the factors affecting dysphagia, especially aspiration, following treatment of head and neck cancer.

A retrospective analysis was performed on 57 patients who were referred to our department complaining of dysphagia symptoms following treatment of HNC since 2008. Patients were selected if they were local and regional cancer free at their MBS test. Patients who had any history of cerebrovascular disease that affected swallowing were excluded.

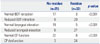

Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The mean age at the time of the MBS test was 62.21 (range, 34-83) years. Thirty-three (57.9%) patients were over 65 years of age. The oropharynx and glottis were the most common primary tumor sites. Dysphagia/aspiration related structures (DARS)3 include the base of the tongue (BOT), pharyngeal constrictors, larynx, and the autonomic neural complex. In this study, 36 patients had primary tumors in DARS. About 70% of the patients had higher clinical stage disease. Various treatment modalities for HNC were used and radiotherapy was performed in 71.9% (n=41) of the patients. In the surgery groups, 65.9% (n=32) of the patients underwent adjuvant treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy. Twenty-seven patients were able to consume a general diet and 20 patients were dependent on tube feeding at initial assessment.

Patients who complained of any dysphagia symptoms were evaluated by physical examination of the head and neck region including laryngoscopy and a sequential MBS test in an upright position. During the MBS test, thin liquids were administered to all subjects with increasing volume (1, 3, 5, 10 cc), and food items of different consistencies were presented at the discretion of an otolaryngologist and speech pathologist.

Penetration was defined as passage of material into the larynx without passing below the vocal folds. Aspiration was defined as passage of material below the level of the vocal folds.4 We recorded and checked the presence or absence of penetration, aspiration (sensate or silent), residue, and abnormal patterns of the pharyngeal phase: reduced BOT retraction, delayed pharyngeal swallowing, pharyngeal contraction weakness, reduced hyolaryngeal elevation, and cricopharyngeal (CP) dysfunction during the MBS test. During the examination, once the problem was identified, compensatory maneuvers such as postural change or alterations in swallowing behavior were taught to lessen the problem, and dynamic examination was performed. After performing the MBS test, findings were rated on an 8-point penetration and aspiration scale (PAS)4 and given a swallowing performance score (SPS) of 1 to 7. In PAS, the clinician's rating for each swallow trial considered the bolus path, depth of penetration/aspiration, and patient response (Table 2).4 Patients with a SPS of 3 or 4 require diet modification and/or a swallowing maneuver. A score of more than 5 suggests a risk of aspiration, while a score of 7 indicates a need for primary tube feeding. Patients with an abnormal swallow (SPS of 3-7) were instructed on compensatory and/or rehabilitative maneuvers. Surgical interventions, such as injection laryngoplasty, bougienation, botox injection to the CP muscle, or CP myotomy, were also utilized. A mean of 27.98 (SD, 42.93) months elapsed between treatment and MBS tests.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Catholic University of Korea.

Reduced BOT retraction (64.9%), reduced laryngeal elevation (57.9%), and CP dysfunction (47.4%) were frequently found on MBS tests (Table 3). Aspiration and penetration were observed in 42.1% (n=24) and 33.3% (n=19) of all tested patients, respectively. Among aspirating patients, aspiration after swallowing was the most common pattern, observed in 60.9% (n=14) of patients.

The abnormal swallowing patterns on MBS between patients with primaries in DARS and patients with primaries at other locations did not differ significantly in this study (p=0.650).

We confirmed whether residue remained in the vallecula, pyriform sinus, or both sites. Residue was found in 32 patients: eight in the vallecula, seven in the pyriform sinus, and 17 in both sites. Residue was identified frequently in patients with reduced BOT retraction (p<0.001), reduced laryngeal elevation (p<0.001), and CP dysfunction (p<0.001) (Table 4).

Reduced BOT retraction was the most common dysphagia pattern and was correlated with clinical stage (p=0.011) and treatment modality (p=0.001). Higher stage (III-IV) disease (21/31, 67.7%) and treatment including radiotherapy (32/41, 78.0%) were significantly associated with reduced BOT retraction. When MBS showed reduced BOT retraction, coexisting residue [relative risk (RR)=5.22], reduced laryngeal elevation (RR=5.405), or CP dysfunction (RR=6.756) were also found.

Radiotherapy was performed more frequently in patients with stage III-IV disease (26/31, 83.9%) than in patients with stage I-II disease (6/14, 42.9%) (p=0.005). Abnormal swallowing was significantly different between groups with or without radiotherapy. Aspiration (p=0.784), penetration (p=0.537), and PAS (p=0.660) did not differ between patients with radiotherapy and those without. However, patients who underwent radiotherapy were significantly more likely to have reduced BOT retraction (32/41, 86.5%) than those who did not (5/16, 13.5%) (p=0.001). Residue was also found significantly more often (p=0.076) in patients who underwent radiotherapy (26/41, 81.2%) than in those who did not (6/16, 18.8%). Even among surgery groups, MBS findings were significantly different between patients with or without adjuvant treatment that included radiotherapy. Patients who underwent adjuvant treatment were significantly (p=0.004) more likely to have reduced BOT retraction (23/31, 82.1%) than those who did not (5/16, 17.9%).

The distributions of PAS and SPS values are shown in Fig. 1. Twenty-four (42%) patients had PAS values over 6, implying aspiration. Forty-one (71.9%) patients had a score of more than 3; 25 (43.9%) patients had a score greater than 5; and 13 patients had a SPS score of more than 7.

Characteristics more frequent in patients (n=20) who had to be fed via a tube at the initial visit than in patients with an oral diet were older age (65.0%), DARS primaries (75.0%), higher stage disease (66.7%), and history of radiotherapy (68.8%). MBS results in tube feeders were reduced BOT retraction (85.0%), reduced laryngeal elevation (95.0%), CP dysfunction (75.0%), aspiration (75.0%), and residue (75.0%) in most patients. Among 20 tube feeders, only 13 patients had a SPS score of 7 at the initial visit. The other seven patients were able to eat orally with the help of diet modification and management.

Aspiration was not significantly related to primary site (p=0.654), DARS (p=0.166), stage (p=0.478), radiotherapy (p=0.784), or adjuvant treatment (p=0.936). Aspiration was found more frequently in patients who had penetration (13/19, 68.4%) than in patients who did not (10/38, 26.3%) (p=0.002).

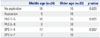

Age was a factor affecting aspiration in HNC patients (p=0.026). We divided the patients into those above and below 65 years old. Primary site, clinical stage, treatments, and feeding status at baseline did not differ significantly. However, aspiration, higher PAS, and higher SPS were found at a significantly higher rate in the older age group (Table 5). To identify risk factors for aspiration independent of age, we investigated aspiration in each age group separately. In the middle age group, a SPS score of more than 5 on MBS test was the only factor affecting aspiration (p<0.001). In the older age group, almost all abnormal findings on MBS, including reduced BOT retraction, delayed pharyngeal swallow, pharyngeal contraction weakness, reduced hyolaryngeal elevation, CP dysfunction, penetration, and even a SPS score over 3, were significantly correlated to aspiration (Table 6).

Swallowing comprises four stages: oral preparatory, oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal. After the voluntary oral phases of swallowing, an involuntary reflex requiring fast and precise coordination between sensory input and motor function occurs.56 Since, dysphagia is a nonspecific diagnosis, we performed a MBS test on patients and calculated PAS and SPS scores to better understand the clinical manifestations of dysphagia. Objective assessment of swallowing function and safety is frequently performed using videofluoroscopic swallowing study, often referred to as a MBS test, which is a validated instrument developed by Logemann, et al.7 The test facilitates radiographic assessment of the structures and dynamics involved in all phases of the swallowing process. The findings of a MBS test are scored using SPS, which provides an accurate assessment of the presence and severity of dysphagia and aspiration risk by combining clinical and radiographic data, and PAS, which encompasses an 8 point, equal appearing interval scale to describe penetration and aspiration events.4

Factors affecting the risk of dysphagia in HNC patients have been reported, and include primary site, treatment modality, age, gender, and comorbidity.8 Patients with oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers reportedly show the greatest risk of post-treatment dysphagia.9 In our study, there was no significant difference in dysphagia and pattern between patients with DARS and non-DARS primaries. Primary site did not seem to impact the course of dysphagia in this study. However, tube feeders were found more often in DARS primaries.

Since the introduction of chemo-radiotherapy, which showed a similar efficacy to that of surgery and adjuvant radiation,10 dysphagia and its sequelae have been increasing.11 Late effects may persist months or years after radiotherapy.1213 Post-radiation edema and radiation-induced fibrosis lead to reduced tissue compliance and immobility of underling muscles. The severity of radiation-induced dysphagia is dependent on total radiation dose, fraction size and schedule, target volumes, treatment delivery techniques, concurrent chemotherapy, genetic factors, presence of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube or nil per os status, smoking, and psychological coping factors.14 In one report, dysphagia was not isolated to treatment with chemo-radiotherapy. In fact, compared to surgery alone, patients treated with all other regimens had higher risks of dysphagia. The risk of swallowing dysfunction was increased for any regimen involving radiotherapy.8 In our study, the most common abnormal pattern observed in the pharyngeal phase was reduced BOT retraction, and patients who underwent radiotherapy were significantly more likely to have reduced BOT retraction and also had more residues on the test. Reduced BOT retraction leads to residue, particularly in the vallecula region, and increases the risk of aspiration after the swallow,15 which was the most common aspiration pattern seen in this study. Ultimately, reduction of BOT retraction by radiotherapy and its associated phenomena increase the risk of aspiration.

Aspiration remains a significant morbidity following HNC treatment. Its prevalence is underreported in the literature because of its often silent nature.16 Silent aspiration and pneumonia was reported in 17 to 81% of patients with stage III-IV HNC. Moreover, long-term use of tube nutrition was reported in as many as 30% of patients.12 In our study, only in 13 (22.8%) patients showed a SPS score of 7 and needed tube feeding at the initial assessment. However, before evaluation, 20 patients reported that they were exclusively dependent on tube feeding. The 7 patients who previously experienced tube feeding did not know that they could eat by mouth before having the test. Tube feeding is time-consuming and is associated with significant costs.17

In our study, when abnormal MBS findings were present, the aspiration rate was lower in the middle age group than in the older age group. In contrast, the aspiration rate was much higher in each abnormal swallowing step in the older age group than the middle age group irrespective of disease stage or treatment. Even a SPS score above 3 affected risk of aspiration in the older age group. In one study, even healthy older adults experienced dysphagia and occasional aspiration18 and had a greater duration of CP opening than younger adults.19 Therefore, in older HNC patients, swallowing evaluation is mandatory irrespective of tumor stage or treatment to identify the patterns of dysphagia and severity in order to provide proper management and to prevent unnecessary tube feeding.

The limitations of our study included the absence of a baseline swallowing study, its retrospective nature, and the selection factors, as only patients who complained of dysphagia underwent a MBS test. Dysphagia may also have been present prior to therapy. Logemann, et al.20 reported a prevalence of pre-treatment dysphagia of 28.2% in patients with oral cancer of stage T2 or above, 50.9% in pharyngeal cancer, and 28.6% in laryngeal cancer. Dysphagia caused by a tumor and increased age may be associated with increased baseline swallowing dysfunction.21 Thus, objective dysphagia testing is recommended before, during, and after treatment in HNC patients.

In summary, reduced BOT retraction was the most common dysphagia pattern and BOT retraction was correlated with clinical stage and treatment regimens that included radiotherapy. Reduction of BOT retraction by radiotherapy and its associated phenomena increase the risk of aspiration. In older patients, aspiration risk was much higher than in younger patients and even single stage abnormality in any swallowing step caused aspiration irrespective of disease stage or treatment. Proper swallowing evaluation, such as a MBS test, should be mandatory, especially in older HNC patients, irrespective of disease stage or treatment, and patients with a higher stage disease who have undergone radiotherapy to identify the exact dysphagia pattern in order to provide proper rehabilitation and to avoid unnecessary tube feeding. With this study, further evidence based studies on the effect of BOT exercises before, during, and after treatment in HNC patients are needed. Also, further studies that describe dysphagia should use more specific scoring systems, such as PAS and SPS, to standardize degree of dysphagia.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) and swallowing performance score (SPS) determined via MBS. Twenty-four (42%) patients had a PAS score over 6, implying aspiration. Patients with a SPS score over 5 are at risk of aspiration and those with a score of 7 absolutely require primary tube feeding. Twenty-five (43.9%) patients had a score over 5 and 13 patients had a score of 7. MBS, modified barium swallow.

Table 1

Patient, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics

Table 2

Eight-Point Penetration-Aspiration Scale

Table 3

MBS Findings Following Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer

Table 4

Relationship between Residue and MBS Findings

Table 5

Relationship between Age and Aspiration

| Middle age (n=24) | Older age (n=33) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No aspiration | 18 | 15 | 0.026 |

| Aspiration | 6 | 18 | |

| PAS 1-5 | 18 | 15 | 0.026 |

| PAS 6-8 | 6 | 18 | |

| SPS 1-4 | 17 | 15 | 0.057 |

| SPS 5-7 | 7 | 18 |

Table 6

The Rate of Aspiration According to Abnormal Swallowing Pattern in Each Age Group

References

1. Nguyen NP, Moltz CC, Frank C, Karlsson U, Nguyen PD, Vos P, et al. Dysphagia severity following chemoradiation and postoperative radiation for head and neck cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2006; 59:453–459.

2. Langerman A, Maccracken E, Kasza K, Haraf DJ, Vokes EE, Stenson KM. Aspiration in chemoradiated patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007; 133:1289–1295.

3. Eisbruch A, Schwartz M, Rasch C, Vineberg K, Damen E, Van As CJ, et al. Dysphagia and aspiration after chemoradiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: which anatomic structures are affected and can they be spared by IMRT? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004; 60:1425–1439.

4. Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996; 11:93–98.

5. Logemann JA. Role of the modified barium swallow in management of patients with dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997; 116:335–338.

6. Garden AS, Lewin JS, Chambers MS. How to reduce radiation-related toxicity in patients with cancer of the head and neck. Curr Oncol Rep. 2006; 8:140–145.

7. Logemann JA, Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR, Ohmae Y, Kahrilas PJ. Normal swallowing physiology as viewed by videofluoroscopy and videoendoscopy. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 1998; 50:311–319.

8. Francis DO, Weymuller EA Jr, Parvathaneni U, Merati AL, Yueh B. Dysphagia, stricture, and pneumonia in head and neck cancer patients: does treatment modality matter? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010; 119:391–397.

9. Laurell G, Kraepelien T, Mavroidis P, Lind BK, Fernberg JO, Beckman M, et al. Stricture of the proximal esophagus in head and neck carcinoma patients after radiotherapy. Cancer. 2003; 97:1693–1700.

10. The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991; 324:1685–1690.

11. Palazzi M, Tomatis S, Orlandi E, Guzzo M, Sangalli C, Potepan P, et al. Effects of treatment intensification on acute local toxicity during radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: prospective observational study validating CTCAE, version 3.0, scoring system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008; 70:330–337.

12. Dysphagia Section, Oral Care Study Group, Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/International Society of Oral Oncology (ISOO). Raber-Durlacher JE, Brennan MT, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Gibson RJ, Eilers JG, et al. Swallowing dysfunction in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012; 20:433–443.

13. Pauloski BR, Rademaker AW, Logemann JA, Newman L, Mac-Cracken E, Gaziano J, et al. Relationship between swallow motility disorders on videofluorography and oral intake in patients treated for head and neck cancer with radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Head Neck. 2006; 28:1069–1076.

14. Platteaux N, Dirix P, Dejaeger E, Nuyts S. Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Dysphagia. 2010; 25:139–152.

15. Langmore SE, Grillone G, Elackattu A, Walsh M. Disorders of swallowing: palliative care. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009; 42:87–105.

16. Nguyen NP, Frank C, Moltz CC, Vos P, Smith HJ, Bhamidipati PV, et al. Aspiration rate following chemoradiation for head and neck cancer: an underreported occurrence. Radiother Oncol. 2006; 80:302–306.

17. Murphy BA. Clinical and economic consequences of mucositis induced by chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. J Support Oncol. 2007; 5:9 Suppl 4. 13–21.

18. Butler SG, Stuart A, Leng X, Rees C, Williamson J, Kritchevsky SB. Factors influencing aspiration during swallowing in healthy older adults. Laryngoscope. 2010; 120:2147–2152.

19. Kurosu A, Logemann JA. Gender effects on airway closure in normal subjects. Dysphagia. 2010; 25:284–290.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download