Abstract

Purpose

Coronary flow reserve (CFR) in the non-infarcted myocardium is often impaired following acute myocardial infarction (AMI). However, the clinical significance of CFR in the non-infarcted myocardium is not fully understood. The objective of the present study was to assess whether a relationship exists between CFR and left ventricular remodeling following AMI.

Materials and Methods

We enrolled 18 consecutive patients undergoing coronary intervention. Heart function was analyzed using real-time myocardial contrast echocardiography at one week and six months after coronary angioplasty. Ten subjects were enrolled as the control group and were examined using the same method at the same time to assess CFR. Cardiac troponin I (cTnI) levels were routinely analyzed to estimate peak concentration.

Results

CFR was 1.55±0.11 in the infarcted zone and 2.05±0.31 in the remote zone (p<0.01) at one week following AMI. According to CFR values in the remote zone, all patients were divided into two groups: Group I (CFR <2.05) and Group II (CFR >2.05). The levels of cTnI were higher in Group I compared to Group II on admission (36.40 vs. 21.38, p<0.05). Furthermore, left ventricular end diastolic volume was higher in Group I compared to Group II at six months following coronary angioplasty.

Restoration of adequate tissue perfusion is the goal of reperfusion therapy.1 Microvascular dysfunction in the infarcted myocardium is known to play a functional role in increasing infarct size, hindering left ventricular function and promoting left ventricular remodeling (LVR) during the chronic phases of myocardial infarction.2 However, microvascular function has also been reported as impaired even in the remote regions supplied by normal coronary arteries.3 Nevertheless, the clinical significance of microvascular dysfunction in the remote region has not yet been fully examined.4 Microvascular flow in humans is difficult to observe, and the methods of measuring microvascular flow are also very complex. Coronary flow reserve (CFR) is defined as the magnitude of increased coronary flow from the basal state to that achieved following maximal coronary vasodilation. Since flow resistance is primarily determined by the microvasculature, CFR is therefore the primary method of measuring microvascular flow.

Previous studies utilizing CFR have consistently been performed with experimental animal models.5 Several studies were performed using positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or Doppler-tipped flow wire to obtain measures of CFR. However, these methods are invasive or expensive, and difficult for wide utilization in the clinic. In contrast, real-time myocardial contrast echocardiography (RT-MCE) is real-time, non-invasive, and a cost effective and simple method to measure CFR. To date, there are no data using RT-MCE to measure CFR in non-infarcted myocardium. In the present study, we performed RT-MCE with dobutamine to measure CFR in all subjects, because it is highly possible that CFR and LVR are related in the remote regions following acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Eighteen patients (13 males and 5 females, mean age of 58.8 years) suffering from AMI were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) first AMI; 2) single-vessel disease; 3) successful recanalization by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (defined as <20% of residual stenosis and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade 3; and 4) within 12 hours following the onset of symptoms. Myocardial infarction was diagnosed by chest pain lasting more than 30 minutes, ST-segment elevation of >0.2 mv in at least two contiguous electrocardiographic leads, and 2-fold increase in serum creatinine kinase or Troponin I (TnI) level. Patients with an unstable condition, malignant arrhythmias, severe extra-cardic disease, or severe valve disease were excluded. A control group included 10 subjects (6 males and 4 females, mean age of 53.4 years) with normal wall motion and coronary arteries. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fourth Hospital of Harbin Medical University, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

This study included eighteen patients undergoing absolute revascularization with PCI within 12 hours following AMI. Cardial TnI (cTnI) was analyzed on admission as a serum specific marker of myonecrosis, and the analysis was repeated every six hours during the first 24 hours post-PCI in order to assess infarct size and severity of infarction.

All patients were subjected to two-dimensional echocardiography (2-DE) and RT-MCE to assess left ventricular (LV) function and CFR one week following PCI. RT-MCE was performed both at rest and during dobutamine infusion in the infarcted region and remote regions to assess CFR. After six months, 2-DE was repeated to reassess LV function.

All patients received antiplatelet treatment with clopidogrel and aspirin. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I), angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) and β-blocker were routinely administered, if not contraindicated, and well tolerated.

The infarct-related artery was treated with stent implantation in all patients. Successful primary angioplasty was defined as a final TIMI flow grade 3 in the infarct-related artery and residual stenosis of <20%. All patients received 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel prior to PCI. Coronary angiography was performed to select corresponding myocardial territory for each artery.

2-DE (Philips iE33, USA) was performed one week following successful PCI and prior to RT-MCE. Left ventricular end diastolic volume (LVEDV), left ventricular end systolic volume (LVESV) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were measured. LV volumes were calculated using the modified Simpson's biplane method. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. LVEF was assessed as the percentage change in LV volume from end-diastole to end-systole. In order to assess the extent of post-infarct LVR, 2-DE was repeated at six months following PCI.

RT-MCE was performed in three apical views (apical 4-, 2-, and 3-chamber) one week following PCI using low-power continuous, power-modulation MCE in a mechanical index of 0.2. All subjects underwent infusion of SonoVue (Bracco, Milan, Italy) at 50-70 mL/h with an infusion syringe-pump. The infusion rate was adjusted for each patient to optimize myocardial opacification with minimal attenuation. Once optimized, the machine settings were maintained throughout the study. To assess the replenishment kinetics, flash echocardiography at a high mechanical index of 1.4 was applied for transient microbubble destruction in the myocardium. We acquired sequences of low-power (0.2) myocardial perfusion images containing at least 15 cardiac cycles following the flash echocardiography. The procedure was repeated for each apical view.6 SonoVue infusion was administered again two minutes after the end of dobutamine infusion at the same rate as provided at baseline. Dobutamine was infused intravenously at a starting dose of 5 ug/kg/min, followed by an increasing dose of 10 ug/kg/min up to a dose of 20 ug/kg/min in three minutes stages.7 Drugs that were considered to influence coronary microcirculation were withdrawn at 24 hours. Heart rate, systemic blood pressure, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram were recorded at each stage of dobutamine infusion. Dobutamine infusion was stopped if the patient developed serious complications, such as significant hypertension [systolic blood pressure (SBP) >220 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) >120 mm Hg], hypotension (SBP drop of >40 mm Hg), intolerable symptoms, a persistent arrhythmia, gross electrocardiogram changes, or intolerable side effects. MCE images were acquired in the same sequence as rest images.

The LV was divided into 17 segments.8 We chose infarcted regions far away from remote regions, to ensure that they do not adversely affect each other. We defined the remote and infarct regions as follows: if the left anterior descending (LAD) artery was the infarct-related artery, the anterior segments and/or anteroseptal segments showing hypokinesia at baseline 2-DE represented the area of the infarcted region, and the inferior and/or inferolateral segments represented the remote region. In the right coronary (RCA) or left circumflex artery (LCX) was the infarct-related artery, the converse procedure was used. All of the clear infarct segments were analyzed, and we chose two remote segments to analyze remote regions in each patient. A total of seventy-six myocardial segments (44 infarcted lesions and 32 remote lesions) were studied.

Myocardial blood flow (MBF) was quantified using Q-lab software (Philips Medical System, USA). RT-MCE sequences were analyzed in end-systolic frames, beginning in the frame immediately following the flash and including 15 subsequent cardiac cycles. Regions of interest (ROI) were placed and tracked manually within the myocardium at rest and the corresponding segments after the stressor. The ROI were of similar size, and the high-intensity endocardial and epicardial borders were avoided. The software package automatically calculated mean acoustic intensity of each ROI and generated time-intensity curves that were subsequently fitted to a monoexponential function: y=A (1-e-βt) (q), where A represents the plateau acoustic intensity and β represents the rate of acoustic intensity increase and reflects microbubble velocity. MBF was calculated as the product of A×β. The product of these parameters was correlated well with radiolabeled microsphere-derived MBF. Resting and maximal MBF was derived, and CFR (MBF at stress/MBF at rest) was calculated for each patient. A single value was calculated for each region as the average of all analyzable segments. Segments with artifacts or attenuation were excluded. All images were analyzed independently by two experienced observers, who were blinded to the clinical data, angiographic results, and other respective imaging.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD, and were analyzed using a Student's t-tests. To determine correlations, we used Spearman's rank correlation test. Categorical data were presented as absolute values or percentage and were compared using chi-square or Fisher's exact tests.

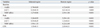

In every patient, PCI restored coronary TIMI flow grade 3 and provided residual stenosis of <20%. Stenting was performed in all patients; among the 18 patients, 13 were males and the mean age was 58.8 years. Twenty-two percent of all patients had diabetes mellitus, 39% of all patients had hypertension, 39% of all patients had hypercholesterolemia, and 44% of all patients were smokers. All patients received aspirin, clopidogrel, and a statin during the follow-up period. ACE-I or ARB and β-blockers were routinely administered, if not contraindicated and if well tolerated. The infarct-related coronary artery was LAD in 8 patients, LCX in 3 patients, and RCA in 7 patients. The mean peak concentration of cTnI was 25.56 ng/mL and the mean time from the onset of symptoms to reperfusion was 5.33 hours. Baseline clinical, angiographic and echocardiographic characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

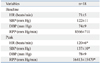

RT-MCE with dobutamine stress was performed without serious complications. Hemodynamic and safety parameters are outlined in Table 2. During low-dose dobutamine infusion, heart rates and SBP increased (p<0.05), while DBP was not different (p>0.05).

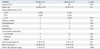

In the infarcted region, the mean resting MBF was 1.27±0.86 dB/s, and it was 1.94±1.33 dB/s during dobutamine infusion. MBF in the remote regions was 2.94±1.06 at baseline and 6.22±2.68 dB/s at stress. Both at baseline and following low dose dobutamine administration, MBF in the remote region was significantly higher than in the infarcted region, and mean CFR of the remote region was also significantly higher than in the infarcted region (2.05±0.31 vs. 1.55±0.11, p<0.01) (Table 3, Fig. 1). There was no difference in MBF between the remote and normal regions at baseline, while MBF in the normal region was significantly increased from that in the remote region at peak stress (p<0.05) (Fig. 2). Mean CFR was also higher than the remote region (2.94±1.06 vs. 2.05±0.31, p<0.01) (Fig. 2).

Mean CFR in the remote region was 2.05. After defining the normal lower limit of CFR as 2.05, the patients were divided into two groups: five patients had impaired CFR (CFR <2.05, Group I) and 13 patients had preserved CFR (CFR >2.05, Group II). No differences were observed between the two groups in terms of age, gender, cardiac risk factors, time from symptom onset to reperfusion, and site of infarct. Medications throughout the hospital stay and during the follow-up period were also similar between the two groups. Peak cTnI was higher in Group I patients than Group II patients (36.40±18.35 vs. 21.38±10.04, p<0.05). Impaired CFR was associated with a greater degree of myocardial damage. Furthermore, impaired CFR in the remote region was linked to impaired CFR in the infarcted region. The characteristics of Group I and II are presented in Table 4.

At one week post-PCI, LVEDV in Group I was higher than in Group II, however, there was no statistically significant difference (129.8 mL vs.128.5 mL, p>0.05). LVEDV in Group I increased compared with Group II (139.8 mL vs. 130.9 mL, p<0.05) at six months following PCI. During the six-month follow-up period, LVEDV and LVESV in Group I increased (129.8 mL vs. 139.8 mL, and 66 mL vs. 71.8 mL, respectively) and LVFF was not improved (49% vs. 49%). LVEDV in Group II slightly increased (128.5 mL vs. 130.9 mL), while LVESV decreased (62.5 mL vs. 61.5 mL) and LVEF increased (51% vs. 53%); however, none of these comparisons reached statistical significance. Changes in LV volumes and LVEF at each time point are described in Table 5. Furthermore, there was a significant negative correlation between CFR and LVEDV in the remote region (r=-0.687, p=0.0016) (Fig. 3). LVESV, LVEF, and CFR all correlated with each other (r=-0.798, p<0.0001; r=0.756, p=0.0003, respectively) (Fig. 3). Impaired CFR led to a significant increase in LVEDV at six months following PCI.

It is well known that PCI is the most effective means to restore patency and adequate reflow in the infarct-related artery in patients with AMI. However, detailed studies have shown that up to 25% of patients undergoing angioplasty lack myocardial reperfusion despite revascularization of the infarct-related artery.9 As a result, cardiac mortality remains high, particularly in patients who develop heart failure. This study was designed to assess the relationship between CFR in the remote region and LVR in patients with a first AMI who underwent successful revascularization. CFR was calculated as the ratio of myocardial blood flow following administration of dobutamine to basal blood flow.10

There were four main findings in the present study. Firstly, no study subjects were excluded due to side effects of dobutamine stress during MCE. The use of MCE for non-invasive quantification of microvascular flow is feasible,11,12 Previous data have suggested a good agreement among MCE, SPECT, and CMR for the evaluation of myocardial perfusion. Secondly, although the infarct-related artery was successfully revascularized, CFR still decreased compared to the normal group, not only in the infarcted region, but also in the remote region. Thirdly, CFR in the remote region correlated with both infarct size and severity. Patients with the greatest impaired CFR had the highest peak cTnI, while cTnI correlated with infarct size. In addition, CFR in the remote region was linked to CFR in the infarcted region. It is possible that it is associated also with extensive necrosis in the shared microvascular. Finally, CFR and LVEDV were negatively correlated. Impaired CFR in the remote regions was proportionally associated with increased LVEDV. Taken together, our data provide evidence of a strong correlation between CFR in the remote region and LVR following reperfusion. Early CFR measured in the remote region can independently predict late LVR following AMI.

CFR in the remote region measured using MCE with dobutamine stress is an effective parameter for predicting LVR in patients with AMI.13,14 Following successful PCI, the average CFR was 2.05 in the remote myocardium, lower than that in the normal subjects, although the remote myocardium was not supplied directly by the infarct-related coronary artery. We observed that both LVEDV and LVESV in patients with impaired CFR were significantly greater than the patients with preserved CFR. Therefore, adequacy of perfusion in the non-infarct region was also important in maintaining LV function, and CFR in the remote region correlated inversely with LVEDV and LVESV. Higher values of CFR within the remote region were predictive for lack of remodeling over six months.

We did not perform MCE with dobutamine stress immediately following the onset of AMI since microvascular dysfunction is a complex and dynamic process that begins during the ischemic period and extends up to 48 hours following reperfusion. The abrupt release of cytotoxic factors, local inflammation and vasoconstriction, peripheral embolization of atherosclerotic debris, platelet plugs and intimal edema can immediately influence microvascular perfusion following reperfusion. Microvascular dysfunction in the non-infarcted myocardium is representative of more extensive necrosis and deterioration of cardiac function. Several possible mechanisms have been proposed,15,16,17,18,19 including impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation, sharing of microvascular systems between the infarcted and non-infarcted myocardium, and vasoconstriction mediated by systemic or local neurohumoral reflexes. Furthermore, cardiospecific overexpression of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor and a decrease in microvessel density in the non-infarcted myocardium have also been observed, which lead to microvascular dysfunction. Experimental studies have confirmed that acute myocardial infarction activates alpha-adrenergic activity to increase vasoconstriction in remote regions normally perfused by coronary arteries. These reasons could explain the observed reduced CFR. Other studies suggest that myocardial damage in the infarcted region may lead to compensatory changes in metabolism imbalance in the remote myocardium, such as consumption of adenosine triphosphate and creatine phosphate, and decreasing levels of glycogen, both confirmed in our laboratory.

In conclusion, effective microvascular reflow within the remote region following reperfusion is a key determinant for preventing LVR. Although we could not clarify the mechanisms of microvascular dysfunction in the remote myocardium, we suggest that impaired CFR in the remote myocardium is a more reliable parameter for estimating microvascular dysfunction.

There are some limitations in the present study. The number of patients was small, the follow-up period was short, and the role of diastolic dysfunction or other factors was not fully examined. A large-scale study is needed to determine the relationship of CFR and LVR following AMI.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

MBF and CFR in the infarcted and remote regions. (A) Both at baseline and after low dose dobutamine administration, MBF in remote region was significantly higher than in the infarcted region. (B) Comparison of CFR in infarcted and remote regions. Mean CFR of the remote region was significantly higher than the infarcted region. MBF, myocardial blood flow; CFR, coronary flow reserve.

Fig. 2

MBF and CFR in the remote and normal regions. (A) No difference was observed in MBF between the remote regions in normal subjects at baseline. At peak stress, MBF in normal subjects was significantly increased compared to the remote region. (B) Correlation between CFR in the remote and normal regions. Mean CFR was higher than in the remote region. MBF, myocardial blood flow; CFR, coronary flow reserve.

Fig. 3

Correlation analyses of CFR in the remote region. (A) There was a significant negative correlation between CFR in the remote region and LVEDV at six months. Impaired CFR leads to a significant increase in LVEDV at follow up. (B) Correlation between CFR and LVESV. There was a significant negative correlation between CFR in the remote region and LVESV. (C) Correlation between CFR and LVEF. There was a positive correlation between CFR and LVEF at follow up. CFR, coronary flow reserve; LVEDV, left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVESV, left ventricular end systolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 3

MBF and CFR in Patients with AMI

MBF, myocardial blood flow; CFR, coronary flow reserve; AMI, acute myocardial infarction.

A represents the plateau acoustic intensity and β represents the rate of acoustic intensity increase and reflects microbubble velocity. MBF was calculated as the product of A×β. CFR was calculated as MBF at stress/MBF at rest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Department of Medical Ultrasonics of the second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. We also thank Dr. Li Xue (the forth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University) and Guoqing Du (the second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University) for providing amendment opinions.

We thank Medjaden Bioscience Limited for assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

1. Funaro S, La Torre G, Madonna M, Galiuto L, Scarà A, Labbadia A, et al. Incidence, determinants, and prognostic value of reverse left ventricular remodelling after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results of the Acute Myocardial Infarction Contrast Imaging (AMICI) multicenter study. Eur Heart J. 2009; 30:566–575.

2. Geshi T, Nakano A, Uzui H, Okazawa H, Yonekura Y, Ueda T, et al. Relationship between impaired microvascular function in the non-infarct-related area and left-ventricular remodeling in patients with myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2008; 126:366–373.

3. Bodí V, Sanchis J, Núñez J, López-Lereu MP, Mainar L, Bosch MJ, et al. [Abnormal myocardial perfusion after infarction in patients with persistent TIMI grade-3 flow. Only an acute phenomenon?]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007; 60:486–492.

4. Pacella JJ, Villanueva FS. Effect of coronary stenosis on adjacent bed flow reserve: assessment of microvascular mechanisms using myocardial contrast echocardiography. Circulation. 2006; 114:1940–1947.

5. Laser A, Ingwall JS, Tian R, Reis I, Hu K, Gaudron P, et al. Regional biochemical remodeling in non-infarcted tissue of rat heart post-myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996; 28:1531–1538.

6. Wei K. Detection and quantification of coronary stenosis severity with myocardial contrast echocardiography. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2001; 44:81–100.

7. Mathias W Jr, Kowatsch I, Saroute AN, Osório AF, Sbano JC, Dourado PM, et al. Dynamic changes in microcirculatory blood flow during dobutamine stress assessed by quantitative myocardial contrast echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2011; 28:993–1001.

8. Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2002; 18:539–542.

9. Wita K, Filipecki A, Lelek M, Bochenek T, Elżbieciak M, Wróbel W, et al. Prediction of left ventricular remodeling in patients with STEMI treated with primary PCI: use of quantitative myocardial contrast echocardiography. Coron Artery Dis. 2011; 22:171–178.

10. Kurita T, Sakuma H, Onishi K, Ishida M, Kitagawa K, Yamanaka T, et al. Regional myocardial perfusion reserve determined using myocardial perfusion magnetic resonance imaging showed a direct correlation with coronary flow velocity reserve by Doppler flow wire. Eur Heart J. 2009; 30:444–452.

11. Armstrong WF, Zoghbi WA. Stress echocardiography: current methodology and clinical applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005; 45:1739–1747.

12. Bolognese L, Carrabba N, Parodi G, Santoro GM, Buonamici P, Cerisano G, et al. Impact of microvascular dysfunction on left ventricular remodeling and long-term clinical outcome after primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004; 109:1121–1126.

13. Lepper W, Hoffmann R, Kamp O, Franke A, de Cock CC, Kühl HP, et al. Assessment of myocardial reperfusion by intravenous myocardial contrast echocardiography and coronary flow reserve after primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [correction of angiography] in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000; 101:2368–2374.

14. Anantharam B, Janardhanan R, Hayat S, Hickman M, Chahal N, Bassett P, et al. Coronary flow reserve assessed by myocardial contrast echocardiography predicts mortality in patients with heart failure. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011; 12:69–75.

15. Neizel M, Futterer S, Steen H, Giannitsis E, Reinhardt L, Lossnitzer D, et al. Predicting microvascular obstruction with cardiac troponin T after acute myocardial infarction: a correlative study with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009; 98:555–562.

16. Wita K, Lelek M, Filipecki A, Turski M, Wróbel W, Tabor Z, et al. Microvascular damage prevention with thrombaspiration during primary percutaneous intervention in acute myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2009; 20:51–57.

17. Coser A, Franchi E, Marini M, Cemin R, Benini A, Beltrame F, et al. Intravenous contrast echocardiography after myocardial infarction: relationship among residual myocardial perfusion, contractile reserve and long-term remodelling. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2007; 8:1012–1019.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download