Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to compare survival of patients with uterine sarcomas using the 1988 and 2008 International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) staging systems to determine if revised 2008 staging accurately predicts patient survival.

Materials and Methods

A total of 83 patients with leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma treated at Yonsei University Health System between March of 1989 and November of 2009 were reviewed. The prognostic validity of both FIGO staging systems, as well as other factors was analyzed.

Results

Leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma comprised 47.0% and 53.0% of this study population, respectively. Using the new staging system, 43 (67.2%) of 64 eligible patients were reclassified. Among those 64 patients, 45 (70.3%) patients with limited uterine corpus involvement were divided into stage IA (n=14) and IB (n=31). Univariate analysis demonstrated a significant difference between stages I and II and the other stages in both staging systems (p<0.001) with respect to progression-free survival and overall survival (OS). Age, menopausal status, tumor size, and cell type were significantly associated with OS (p=0.011, p=0.031, p=0.044, p=0.009, respectively). In multivariate analysis, revised FIGO stage greater than III was an independent poor prognostic factor with a hazard ratio of 9.06 [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.49-33.0, p=0.001].

Uterine sarcomas represent rare tumors that account for up to 7% of all uterine cancer.1 Since uterine sarcomas are rare and exhibit truly heterogeneous histopathologic diversity, optimal treatment strategies have not been well established. Many reports suggest that the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) stage is the most important prognostic factor and should primarily dictate treatment.2,3,4,5,6,7,8

Until 2008, uterine sarcomas were staged using the staging system designed for endometrial carcinomas in 1988. A revised FIGO classification and staging system was introduced in 2008 for uterine sarcomas in order to reflect the differences in the biologic behavior.9,10 Tumor size was introduced as a staging variable in the revised FIGO staging system for uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma. In this new system, stage I disease is divided into IA or IB according to the tumor size. Adnexal involvement is now included within stage II. Thus it is prudent to evaluate the FIGO staging system for its ability to predict prognosis and examine the relevance of changes made periodically to the staging system in an evidence based manner.

The objective of this study was to compare survival for patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma using the 1988 and 2008 the FIGO staging systems to determine if revised 2008 staging accurately predicts patient survival.

A total of 83 patients with leiomyosarcoma (LMS) and endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) were treated at Yonsei University Health System between March of 1989 and November of 2008. Nineteen patients were excluded due to incomplete surgery and difficulty in classification. A final total of 64 patients were included in the study. Demographic data obtained from the medical record included age, parity, body mass index, menopausal status, initial symptoms, cell type, mode of surgery, tumor size, lymph node status, presence of myometrial invasion, and treatment modality.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the date of diagnosis to the date of the first recurrence or progression of disease, or in the absence of recurrence, to the date of the last follow-up or death. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Patients were staged according to both the 1988 and 2008 FIGO staging systems. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test for univariate analysis. Subsequently, multivariate analysis with Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to determine which markers predicted PFS and OS after adjusting for the effects of known prognostic factors (FIGO stage, age, cell type, and tumor size). Data was analyzed using parametric and nonparametric statistics, SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used for patient characteristic data, and are summarized as means and standard deviations. Continuous variables were examined for a normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) before adopting parametric statistics. Generally, for all analyses p<0.05 was considered significant.

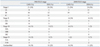

LMS and ESS comprised 47.0% (39/83) and 53.0% (44/83) of the study population, respectively. The median follow-up was 57 months. Table 1 depicts the patient characteristics. Tumor size was significantly larger in patients with LMS, compared to cases with ESS.

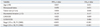

Sixty-four of the 83 patients were classified according to the FIGO staging system. Table 2 shows the comparison of the distribution of patients using the 1988 and 2008 FIGO staging systems. With the 2008 FIGO staging system, the largest numbers of patients (70.3%) were classified as stage I. The percentage of patients classified as stage II markedly increased with the 2008 FIGO staging system (from 0% to 12.5%). Based on the 2008 FIGO system, downstaging occurred in 42 patients (65.6%), and upstaging occurred in one patient (1.6%).

The 5-year estimated survival rates for patients with 1988 FIGO stage IA, IB, and IC disease were 100%, 95%, and 82%, respectively. When these patients were reclassified according to the 2008 FIGO staging system, the 5-year survival rates for stages IA and IB were 100% and 83.0%, respectively (Fig. 1). Patients with 1988 FIGO stage IIIA disease had 5-year estimated survival outcomes similar to those of patients with 2008 FIGO stage IIA disease (63.0% and 60.0%, respectively).

Univariate analysis demonstrated significant differences between stages I, II, and other stages in both staging systems (p<0.001) with respect to PFS and OS (Fig. 2). Myometrial invasion was not associated with survival. However, age, menopausal status, tumor size, and cell type were significantly correlated with OS (p=0.011, p=0.031, p=0.044, p=0.009, respectively) (Table 3, Fig. 3). In multivariate analysis, ESS cell type and 1988 FIGO stage >III were independent prognostic factors with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.22 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.05-0.90, p=0.035] and 6.47 (95% CI 2.03-20.60, p=0.002) respectively. However, there was no difference in survival between LMS and ESS in the multivariate model after adjusting for the 2008 FIGO staging system (HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.08-1.58, p=0.174) (Table 4).

The new FIGO staging systems for LMS and ESS were developed in 2008. Early stage cancer (i.e., stage I) was subclassified into stages IA and IB for the first time by tumor size and not by the depth of myometrial invasion. Modifying the stage I classification was proposed because the prognosis of patients with stage IA, IB, and IC disease was not statistically significant. In our study, the 5-year survival rate of patients with the 1988 stage IC was similar to the 5-year survival rate of patients with the 2008 stage IB (82% vs. 83%). It was also noteworthy that the 1988 FIGO stage IIIA disease and 2008 FIGO stage IIA had similar survival (63% and 60.0%, respectively).

Various clinicopathologic studies on uterine sarcomas have found that stage is an important independent predictor of OS.2,3,4,5,6 However, the impact of other prognostic factors including age, tumor size, FIGO stage, depth of myometrial invasion, tumor grade, mitotic activity, and DNA ploidy on survival is unclear or controversial, especially for ESS.11,12,13 In the largest study of low endometrial stromal sarcoma (LESS), tumor size correlated poorly with outcome, but, mitotic activity and cytologic atypia were not predictive of tumor recurrence in stage I tumors.14

ESS has traditionally been divided into LESS and high-grade ESS (HESS) according to morphology, mitotic activity, cellularity, and the presence of necrosis. HESS is characterized by an aggressive clinical course, thus, it has been suggested that HESS should be reclassified as an undifferentiated or poorly-differentiated endometrial sarcoma and not remain part of the ESS category.15,16 However, in this study, histologic subtype did not impact survival. Because of the rarity of ESS, only 4 cases of HESS were included in our study.

In a study of 208 LMS patients, tumor size was a major prognostic factor, and tumor grade and stage were parameters predictive of prognosis.17 Abeler, et al.2 demonstrated that tumor size and the mitotic index were significant prognostic factors (p<0.0001) in LMS confined to the uterus. According to previous studies, lymph node metastases have been identified in 6.6% and 11% of patients with LMS who underwent lymphadenectomy.17,18 The 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 26% in patients who had positive lymph nodes compared with 64.2% in patients who had negative lymph nodes (p<0.001).17 In our study, 64% of patients did not undergo lymph node evaluation; therefore, limited data were available from which to draw conclusions.

Our study shows that stage, tumor size, age, menopausal status, and cell type (LMS vs. ESS) were significant prognostic factors in univariate analysis. The depth of myometrial invasion was associated with DFS but not OS. This result reflects that the decision to change dividing stage I disease according to the tumor size seems appropriate. The presence of adnexal involvement resulted in downstaging in the revised FIGO staging system. In this study, the 5-year estimated survival rates of patients with 1988 stage IIIA and 2008 stage IIA were 63.0% and 60.0%, respectively. Therefore, revisions appear appropriate based on similar survival outcomes in patients with adnexal invasion. The revised staging system discriminates among the early stage patients more than the advanced stage patients. The revised FIGO stage was an independent parameter in multivariate analysis. However, the number of patients with advanced stage disease was too small to show the comparison survival outcome by staging system.

There are some limitations to our study. A relatively small number of patients were included in the analysis. Additionally, this retrospective chart review may have unmeasured confounders. However, this is the first report to show the discriminating impact of survival outcomes between the 1988 and 2008 staging systems for uterine sarcomas.

Standard staging procedures for uterine sarcoma have not yet been determined. The utility of procedures for peritoneal staging, including peritoneal washing cytology, peritoneal biopsy, and omentectomy in the absence of gross extrauterine disease, needs further evaluation to verify the impact on survival. More definitive conclusions regarding the revised FIGO staging system for uterine sarcomas may be validated with larger populations involving multiple centers.

In conclusion, the 2008 FIGO staging system is more valid than the previous system for LMS and ESS with respect to its ability to distinguish early stage patients from patients with advanced stage disease. However, no significant prognostic validity was observed between stage III and IV due to the rare occurrence of patients in those stages.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Survival curves for patients with stage I disease according to the 1988 FIGO staging system (A) and 2008 FIGO staging system (B).

Table 1

Patient Characteristics

LMS, leiomyosarcoma; ESS, endometrial stromal sarcoma; BMI, body mass index; TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; LN, lymph node; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiation.

*t-test.

†Mann-Whitney U test.

‡Chi-square test.

§Fisher's exact test.

∥Staging operation includes TAH, BSO, pelvic and paraaortic lymph node assessment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (NRF-2012R1 A1A2004523 and NRF-2012R1A1A2040271).

References

1. Major FJ, Blessing JA, Silverberg SG, Morrow CP, Creasman WT, Currie JL, et al. Prognostic factors in early-stage uterine sarcoma. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 1993; 71:4 Suppl. 1702–1709.

2. Abeler VM, Røyne O, Thoresen S, Danielsen HE, Nesland JM, Kristensen GB. Uterine sarcomas in Norway. A histopathological and prognostic survey of a total population from 1970 to 2000 including 419 patients. Histopathology. 2009; 54:355–364.

3. Kildal W, Abeler VM, Kristensen GB, Jenstad M, Thoresen SØ, Danielsen HE. The prognostic value of DNA ploidy in a total population of uterine sarcomas. Ann Oncol. 2009; 20:1037–1041.

4. Akahira J, Tokunaga H, Toyoshima M, Takano T, Nagase S, Yoshinaga K, et al. Prognoses and prognostic factors of carcinosarcoma, endometrial stromal sarcoma and uterine leiomyosarcoma: a comparison with uterine endometrial adenocarcinoma. Oncology. 2006; 71:333–340.

5. Koivisto-Korander R, Butzow R, Koivisto AM, Leminen A. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors in 100 cases of uterine sarcoma: experience in Helsinki University Central Hospital 1990-2001. Gynecol Oncol. 2008; 111:74–81.

6. Park JY, Kim DY, Suh DS, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim YT, et al. Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes of patients with uterine sarcoma: analysis of 127 patients at a single institution, 1989-2007. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008; 134:1277–1287.

7. Kahanpää KV, Wahlström T, Gröhn P, Heinonen E, Nieminen U, Widholm O. Sarcomas of the uterus: a clinicopathologic study of 119 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1986; 67:417–424.

8. Kim WY, Chang SJ, Chang KH, Yoon JH, Kim JH, Kim BG, et al. Uterine leiomyosarcoma: 14-year two-center experience of 31 cases. Cancer Res Treat. 2009; 41:24–28.

9. Kim HS, Song YS. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system revised: what should be considered critically for gynecologic cancer? J Gynecol Oncol. 2009; 20:135–136.

11. Bodner K, Bodner-Adler B, Obermair A, Windbichler G, Petru E, Mayerhofer S, et al. Prognostic parameters in endometrial stromal sarcoma: a clinicopathologic study in 31 patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2001; 81:160–165.

12. Chan JK, Kawar NM, Shin JY, Osann K, Chen LM, Powell CB, et al. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: a population-based analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008; 99:1210–1215.

13. Haberal A, Kayikçioğlu F, Boran N, Calişkan E, Ozgül N, Köse MF. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the uterus: analysis of 25 patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003; 109:209–213.

14. Chang KL, Crabtree GS, Lim-Tan SK, Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Primary uterine endometrial stromal neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 117 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990; 14:415–438.

15. Evans HL. Endometrial stromal sarcoma and poorly differentiated endometrial sarcoma. Cancer. 1982; 50:2170–2182.

16. Amant F, Vergote I, Moerman P. The classification of a uterine sarcoma as 'high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma' should be abandoned. Gynecol Oncol. 2004; 95:412–413.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download