Abstract

Atrial tachycardia (AT) originating from the aortomitral junction is a very rare and challenging disease. Its arrhythmic characteristics have not been described in detail compared with the descriptions of the arrhythmic characteristics of AT originating from the other locations. Only a few case reports have documented successful ablation of this type of AT using transaortic or transseptal approaches. We describe a case with AT that was resistant to right-sided ablation near the His bundle failed and transaortic ablation at the aortomitral junction successfully eliminated.

Atrial tachycardia (AT) is one of supraventricular tachycardias that have been demonstrated to be successfully ablated with minimal risk.1 AT usually originates from specific sites such as crista terminalis,2,3 superior vena cava,4 tricuspid annulus,5 ostium of the coronary sinus,6 the pulmonary veins, and the mitral annulus.7 However, the arrhythmic characteristics of AT originating from the aortomitral junction have not been described in detail.8-10 We report herein a case of a 37-year-old woman with this type of AT that was successfully ablated using a transaortic approach.

A 37-year-old woman with no relevant medical history was admitted to our center after 2 years of recurrent disabling episodes of palpitation and dizziness. She presented with abrupt onset and offset clinical tachycardia. The baseline electrocardiogram (ECG), chest radiograph, and echocardiogram were normal. The ECG recorded during an episode of palpitation revealed a narrow QRS complex tachycardia with a cycle length of 350 ms. The P-wave polarity was isoelectric in lead I and biphasic (initially negative with a late positive component) in leads V1 and V3. In addition, the P-wave polarity was positive in the inferior leads (II, III, and aVF) and negative in lead aVL (Fig. 1).

After obtaining informed consent, we performed an electrophysiological study without sedation. Two quadripolar catheters were introduced into the right ventricle and His bundle region via the femoral vein. A 20-pole catheter with an interelectrode spacing of 2-5-2 mm was positioned at the lateral right atrium (RA), with its distal 10 electrodes in the coronary sinus. Ventriculoatrial conduction was absent at baseline and during isoproterenol infusion. Tachycardia was induced by burst pacing from the RA during isoproterenol infusion without a "jump-up" in the atrial-His (A-H) interval. The tachycardia was perpetuated regardless of the spontaneous AV block. The entrainment phenomenon was not observed during atrial pacing. An intravenous bolus injection of 2-mg adenosine 5'-triphosphate during tachycardia reproducibly terminated the tachycardia without any development of AV block. Ventricular overdrive pacing during tachycardia resulted in AV dissociation without tachycardia entrainment.

Activation mapping in the RA during tachycardia revealed the earliest atrial activation at the His bundle region, which preceded the onset of the P wave by 30 ms on the surface ECG. Radiofrequency energy was delivered to the superoseptal RA, where the earliest RA activation was recorded, using a 7 F, 4-mm-tipped ablation catheter (Blazer II, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), with a maximal temperature of 55℃ and maximal power output of 35 W. The His bundle potential was not recorded from the ablation sites at the right superoseptum. The tachycardia was terminated with junctional beats. However, the tachycardia was still inducible and sustainable after the ablation at these sites. To find the other earliest atrial activation site, mapping was then performed around the left atrial septum. The activation at the left atrial septum close to the His-bundle region during the tachycardia was later than that at the right His-bundle region. Subsequently, detailed activation mapping was performed at the aortic sinus of Valsalva, using a transaortic approach, after the aortography. The local atrial electrogram inside the noncoronary aortic and left coronary sinuses preceded the onset of the surface P wave by 40 and 50 ms, respectively. Radiofrequency energy was delivered in the left coronary sinus. Although the tachycardia was terminated by the ablation, it was still inducible. Finally, the earliest site of atrial activation was found at the aortomitral junction where the local atrial electrogram preceded the onset of the surface P wave by 70 ms (Fig. 2). A single radiofrequency energy application at this site using the same ablation catheter with maximal temperature and power output of 50℃ and 30 W, respectively, terminated the tachycardia in 12 s. Thereafter, atrial tachycardia was no longer inducible regardless of isoproterenol infusion (Fig. 3). Neither junctional beats nor prolongation of the A-H interval occurred during or after the energy application. During a 12-month of postablation follow-up period, the patient has been free from recurrence of atrial tachycardia without any antiarrhythmic medications.

Ectopic AT originating from the area proximal to the aortic coronary cusp is a rare disease, and its mechanism has been increasingly investigated. Recent studies have shown that AT originating from the non-coronary cusp (NCC) have been successfully ablated with minimal risk.11-13 On the other hand, however, only a few case reports have demonstrated successful ablation of AT of either left coronary cusp (LCC) or aortomitral junction origin. The term aortomitral junction has been used to indicate the region where the aortomitral continuity joins the left ventricular myocardium. In previous experimental studies, the tissue surrounding the aortic coronary cusp was regarded as a strongly arrhythmogenic site14 because of the abnormal conduction and automaticity of the aortomitral continuity. Its special structure is also known as the "subaortic curtain", which simultaneously supports 2 of the aortic cusps (left and non-coronary) and the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve.15 It exhibits AV nodelike electrophysiological properties and gives rise to catecholamine-induced activity because of delayed afterdepolarizations.16

According to Chen, et al.,2 the major criteria of classification were whether 1) automatic AT could be initiated only by isoproterenol; 2) AT related to reentry or triggered activity could be initiated or terminated by programmed electrical stimuli; 3) only AT related to triggered activity had early or delayed afterdepolarization recorded in the monophasic action potential; and 4) only AT related to reentry had entrainment phenomenon during atrial pacing. In this case, the entrainment phenomenon was not observed during atrial pacing. Markowitz, et al.17 reported that adenosine-sensitive atrial tachycardia is typically focal in origin and due to triggered activity or, far less commonly, automaticity. Therefore, the mechanism of tachycardia in this case might be related with triggered activity rather than reentry. However, because we did not record monophasic action potential, we could not completely differentiate between AT related with reentry from triggered activity.

A positive P wave in leads I and aVL was more likely to indicate AT originating from the NCC, whereas a negative/positive or isoelectric P wave indicated AT originating from the LCC.10 Because the aortomitral junction is located between NCC and LCC, the P waves in leads I and aVL can be negative/positive or isoelectric during AT originating from the aortomitral junction. In the present case, the P waves in lead aVL were negative, consistent with that of a previous study by Wang, et al.10 They reported that the P wave in leads I and aVL was negative/positive in 4 and isoelectric in 2 out of 6 patients with LCC or aortomitral junction AT. One patient had also a positive P wave in leads V1, and II, III, and aVF. Shehata, et al.9 reported that 2 aortomitral junction AT patients had a positive P wave in leads V1, and II, III, and aVF. In our case, the P waves were not as narrow as those of AT originating from the His-bundle region. This finding was consistently observed in the cases reported by Shehata, et al.9 and might be caused by a more left-sided location than an HB-region tachycardia.

The electrogram in the ablation site showed double potentials, which was consistent with those of the previously reported cases.9 The likely substrate for atrial arrhythmia ablation in this region is the adjacent RA or left atrial myocardium behind the thin aortic wall at the level of the sinotubular junction. Although the first potential (arrow) was eliminated, the second one (broken arrow) persisted even after the radiofrequency application. Therefore, the first potential might reflect an activity from AT origin while the second reflect a far-field activity from the atrium. However, the first potential might also be a far field potential originating from aortomitral junction because the tachycardia was not terminated within 10 s.

Conflicting views continue to exist regarding the methods of approaching the aortomitral junction. Some electrophysiologists suggest that a transseptal approach might be safer than the transaortic approach, obviating the need for aortography or coronary angiography.9 However, we herein showed that a transaortic approach may be performed without any complication.

In conclusion, AT could originate from the aortomitral continuity. In selected cases with unsuccessful ablation of AT at the right and left superoseptum, and noncoronary and left coronary sinuses, the aortomitral junction may be considered as a possible alternative site for ablation.

Figures and Tables

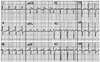

Fig. 1

Surface 12-lead electrocardiogram during an episode of palpitation, showing a narrow QRS complex tachycardia with a cycle length of 350 ms. The P-wave polarity preceding the QRS complex was isoelectric in lead I and biphasic in leads V1 and V3.

Fig. 2

Intracardiac electrograms and ablation signal at the earliest mapped location in the aortomitral junction. The earliest atrial activation (arrow) was found at the aortomitral junction, where the local electrogram recorded from the distal electrodes of the ablation catheter during tachycardia preceded the onset of the surface P wave by 70 ms. Note that the earliest atrial electrogram recorded from the distal ablation catheter (ABLd) also has a large ventricular potential. Tachycardia was terminated 12 s after radiofrequency application. RA, right atrium; CS, coronary sinus; RV, right ventricle.

Fig. 3

Fluoroscopic images in orthogonal fluoroscopic view. (A and B) The successful catheter ablation (ABL) site in the right anterior oblique (RAO) and left anterior oblique (LAO) views, located in the aortomitral junction. (C and D) Aortic root angiograms taken from a pigtail catheter placed at the right coronary cusp (RCC), with the same fluoroscopic angles before ablation. In the RAO view, the RCC overlaps with the left coronary cusp (LCC), and the most anterior aspect is the junction of RCC/LCC. In this view, the NCC is located at the most posterior aspect of the aorta. In the LAO view, the RCC overlaps with the NCC, and the most rightward aspect is the junction of NCC/RCC. The LCC is located at the most leftward aspect in this view. Another mapping catheter (Map) in the RA positioned at the unsuccessful ablation site near the right His-bundle region. CS, coronary sinus; RV, right ventricle; NCC, non-coronary cusp.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported in part by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012-0007604, 2012-045367), and the Korean Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare (A121668).

References

1. Kay GN, Chong F, Epstein AE, Dailey SM, Plumb VJ. Radiofrequency ablation for treatment of primary atrial tachycardias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993; 21:901–909.

2. Chen SA, Chiang CE, Yang CJ, Cheng CC, Wu TJ, Wang SP, et al. Sustained atrial tachycardia in adult patients. Electrophysiological characteristics, pharmacological response, possible mechanisms, and effects of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 1994; 90:1262–1278.

3. Kalman JM, Olgin JE, Karch MR, Hamdan M, Lee RJ, Lesh MD. "Cristal tachycardias": origin of right atrial tachycardias from the crista terminalis identified by intracardiac echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998; 31:451–459.

4. Dong J, Schreieck J, Ndrepepa G, Schmitt C. Ectopic tachycardia originating from the superior vena cava. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002; 13:620–624.

5. Morton JB, Sanders P, Das A, Vohra JK, Sparks PB, Kalman JM. Focal atrial tachycardia arising from the tricuspid annulus: electrophysiologic and electrocardiographic characteristics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001; 12:653–659.

6. Volkmer M, Antz M, Hebe J, Kuck KH. Focal atrial tachycardia originating from the musculature of the coronary sinus. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002; 13:68–71.

7. Kistler PM, Sanders P, Fynn SP, Stevenson IH, Hussin A, Vohra JK, et al. Electrophysiological and electrocardiographic characteristics of focal atrial tachycardia originating from the pulmonary veins: acute and long-term outcomes of radiofrequency ablation. Circulation. 2003; 108:1968–1975.

8. Otomo K, Nagata Y, Uno K, Iesaka Y. "Left-variant" adenosine-sensitive atrial reentrant tachycardia ablated from the left coronary aortic sinus. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008; 31:247–250.

9. Shehata M, Liu T, Joshi N, Chugh SS, Wang X. Atrial tachycardia originating from the left coronary cusp near the aorto-mitral junction: anatomic considerations. Heart Rhythm. 2010; 7:987–991.

10. Wang Z, Liu T, Shehata M, Liang Y, Jin Z, Liang M, et al. Electrophysiological characteristics of focal atrial tachycardia surrounding the aortic coronary cusps. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011; 4:902–908.

11. Das S, Neuzil P, Albert CM, D'Avila A, Mansour M, Mela T, et al. Catheter ablation of peri-AV nodal atrial tachycardia from the noncoronary cusp of the aortic valve. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008; 19:231–237.

12. Kriatselis C, Roser M, Min T, Evangelidis G, Höher M, Fleck E, et al. Ectopic atrial tachycardias with early activation at His site: radiofrequency ablation through a retrograde approach. Europace. 2008; 10:698–704.

13. Ouyang F, Ma J, Ho SY, Bänsch D, Schmidt B, Ernst S, et al. Focal atrial tachycardia originating from the non-coronary aortic sinus: electrophysiological characteristics and catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48:122–131.

14. Wit AL, Cranefield PF. Triggered activity in cardiac muscle fibers of the simian mitral valve. Circ Res. 1976; 38:85–98.

16. Marrouche NF, SippensGroenewegen A, Yang Y, Dibs S, Scheinman MM. Clinical and electrophysiologic characteristics of left septal atrial tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 40:1133–1139.

17. Markowitz SM, Nemirovksy D, Stein KM, Mittal S, Iwai S, Shah BK, et al. Adenosine-insensitive focal atrial tachycardia: evidence for de novo micro-re-entry in the human atrium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49:1324–1333.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download