Abstract

Purpose

Blood pressure variability (BPV) is emerging as an important cardiovascular prognostic factor in addition to average blood pressure level. While there have been some suggestions for the determinants of the blood pressure variability, little is known about the relationship between the blood pressure variability and health-related quality of life (QOL).

Materials and Methods

Fifty-six men and women with mild hypertension were enrolled from local health centers in Republic of Korea, from April to October 2009. They self-monitored their blood pressure twice daily for 8 weeks. Pharmacological treatment was not changed during the period. Standard deviation and coefficient of variation of blood pressure measurements were calculated as indices of BPV. Measurements of QOL were done at initial and at 8-week follow-up visits.

Results

Study subjects had gender ratio of 39:41 (male:female) and the mean age was 64±10 years. The mean home blood pressure's at week 4 and 8 did not differ from baseline. Total score of QOL at follow-up visit and change of QOL among two measurements were negatively correlated to BPV indices, i.e., higher QOL was associated with lower BPV. This finding persisted after adjustment for age, gender and the number of antihypertensive agents. Among dimensions of QOL, physical, mental and hypertension-related dimensions were associated particularly with BPV.

While main focus in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension is still on the mean blood pressure, blood pressure variability (BPV) has been suggested as a significant prognostic indicator in recent studies,1,2 independent of average blood pressure level. However, not much is known regarding determinants of BPV, Some studies showed that BPV may be influenced by the choice of antihypertensive agents,3,4 and other associated factors such as sleep disorders,5 environmental stimuli,6 age, personality and alcohol consumption7 have also been described. Previous observational study8 indicated that cardiovascular diseases are associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms, which can potentially influence various hemodynamic factors including blood pressures. Wider fluctuation of blood pressure may be related to perception of life quality either appropriate or not. Sakakura, et al.9 reported the association of exaggerated BPV with cognitive dysfunction and poor quality of life (QOL) in the elderly, and Okano, et al.10 showed that base blood pressure during sleep is related to health-related QOL. These two studies evaluated BPV on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. The aim of this work is to investigate the association of day-to-day BPV with health-related QOL in hypertensive patients.

Subjects were participants of clinical trial evaluating the effect of cognitive behavior therapy-based 'forest therapy' program in hypertensive patients. Fifty-six men and women were enrolled for the study, being referred from two local health centers. Recruitment was mainly done by self-referral by local advertisement and referral from physicians in the health centers. Subjects had stage I hypertension or prehypertension, with or without antihypertensive medications. They were assigned to either to the experimental group who participated in the forest therapy program or the control group who did only self-monitoring of blood pressure for 8 weeks without participation to the program. This was done by convenient assignment and not true randomization, considering the subjects' preference and feasibility to actual participation of the forest therapy program, i.e., patients chose whether to participate in the forest therapy program or not. They were instructed not to change their antihypertensive medication during the study period, and if prescribing local physician requested the change of their regimen, the patient was dropped out. Finally, 28 persons in each groups finished 8-week follow-up schedule. Inclusion and exclusion criteria, process of enrollment and the contents of the forest therapy program and the additional test such as salivary cortisol level are described in previously published results of the trial.11

Informed written consents were obtained from all the subjects before the participation of the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul Paik Hospital, Inje University, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Manual office BP measurements by mercury sphygmomanometers were done in the local health centers at initial visit and after completing the program (at the day 3 in the control group) by a research nurse, maintaining the same environment in both groups by the conventional methods.11

Home BP monitoring was done for 8 weeks as follows and used for calculation of day-to-day BPV: after 5 min rest, seated, one measurements were done in the morning before drug intake (6-10 am) and the other in the evening (6-10 pm) with designated BP monitor (UA-767, A&D, Tokyo, Japan) and recorded by patients. Measurements on the other timings were not prohibited. All values measured on the first day were excluded from analysis.

A QOL measurement tool developed by Kim, et al.12 was used, which is based on widely used existing QOL tools such as CHO-60, MOS SF-36, and Duke-UNC Health profile. This consists of 5 domains which are general health (GH), physical (PD), mental (MD), social (SD), and hypertension (HTN)-related dimension. The number of questions is 23 and each question has 5-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 23 to 115, the higher the score, the better the QOL. This tool is a version of 'disease-specific' QOL measurement tool which includes some questions specific for hypertensive patients and can be used for evaluation of QOL in hypertensive patients. Measurements were done at initial visits and at 8 weeks.

Day-to-day variability of blood pressure was defined as the standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV= SD/mean) of measurements of 8 weeks total, morning BP's and evening BP's, respectively. Continuous variables were described as mean±SD, or median (25-75 percentile) if a variable was not normally distributed. Comparisons of means between the 2 groups were done by Student's t-test, or Wilcoxon's rank sum test in variables not normally distributed. All comparisons were done by 2-tailed tests. In t-test with unequal variances between the groups, Satterthwaite degrees of freedom were used. To compare overall longitudinal BP change between 2 groups, repeated measure ANOVA was used with addition of interaction term between group and measurement timing. To determine predictors of BPV, multiple regression models with BPV parameters as dependent variables and variables which showed significant association with BPV in bivariate analysis were included as explanatory variables. Starting with stepwise regression applying backward selection with elimination p=0.15, empirical exploration was done to maximize explanatory power of the model. p-value below 0.05 was considered as being statistically significant. The statistical package used for the analysis was Stata/MP 12.1 for Windows (32-bit) (College Station, TX, USA).

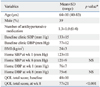

General characteristics of the study subjects are described in Table 1. Blood pressure control status seemed to be good in the majority of patients with mean systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure in 130's and 70's. Antihypertensive medication was being taken by 79% of the subjects, and the number of medication was mainly 1 or 2 except for 6 subjects. Home BP did not change significantly during 8 weeks. Total score of QOL was significantly improved at 8th week compared to the baseline. As previously published, general clinical characteristics were not different between the groups, and QOL improvement was significantly greater in forest therapy group (data not shown).11

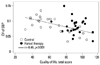

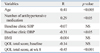

Correlates of BPV as standard deviation of SBP's during 8 weeks are shown in Table 2. Older age and larger number of antihypertensive medication were associated with high BPV. Total score of QOL correlated inversely with BPV. BPV as coefficient of variation showed same pattern of association. Parameters of BPV were not significantly different between male and female subjects (as SD, male 10.4±0.8, female 10.3±0.5, p=0.92) and not influenced by the treatment group (as SD, control group 10.6±0.7, forest therapy group 10.1±0.6, p=0.60). Fig. 1 is a scatter plot showing the relationship between total score of QOL and BPV as coefficient of variation of SBP's. Even though the forest therapy group (shown in solid dots) apparently tended to have higher QOL score than the control group (shown in hollow dots), BPV was not different between the two groups.

Multiple regression model with standard deviation of SBP's during 8 weeks as a dependent variable (Table 3) showed that higher total score of QOL was associated with lower BPV after adjustment for age, gender and use of antihypertensive medication (p<0.0001).

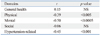

Among various domains of QOL, physical, mental and hypertension-related dimension were inversely correlated to BPV at 8th week measurement, while GH and social dimension were not (Table 4). Any domain of the baseline QOL measurement was not significantly associated with BPV.

This study is the first to show the relationship between the QOL and day-to-day BPV. Previous studies9,10,13 which reported the association of QOL and BPV utilized 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring and mainly focused on diurnal pattern. However, recent studies suggested that day-to-day or visit-to-visit BPV, rather than diurnal variation, is an important prognostic indicator.1,2,14 Our results showed the BPV over 8-week period, calculated from daily measurements of home BP, had significant association with the QOL evaluated by hypertension-specific QOL measurement tool.

While not much has been known for determinants of BPV, it is highly probable that some psychological and/or cognitive factors are closely related, because blood pressure shows prompt and wide variation in response to environmental stimuli and its consequential psychological response.15 QOL reflects subjective perception and appraisal to the current status of life and estimated poor QOL may mean that perception of daily environment stimuli tends to be in a predominantly negative direction. In addition to subjective aspects of perceptive process, if life quality of a certain person is truly compromised, he or she would be more likely to experience frequent and/or strong daily environmental stimuli eliciting negative emotions, which may result in increased BPV.

The reason is not clear why certain domains of the QOL were more closely related to BPV than the others. In our data, physical, mental and hypertension-related domains significantly correlated to BPV while general health and social domains did not. And it is also not well-explained why QOL at week 8 follow-up showed significant association with BPV while baseline QOL did not. There may be some possible influence of behavioral intervention which this study originally intended.

The study subjects were participants of clinical trial to investigate the effect of the cognitive behavior therapy-based 'forest therapy' program in hypertensive patients. Previously published results of the trial showed that forest therapy group showed significantly more improvement of QOL and decrease of salivary cortisol at 8-week follow up while BP change was not different between groups.11 While the QOL increased more in forest therapy group, control group also showed some increase of QOL, probably reflecting nonspecific regression to mean. Previous cross-sectional study reported that lower QOL in hypertensive patients was related to the awareness of the disease and consequently negative psychological response and not the disease itself.16 Probably, intervention of forest therapy may influence QOL positively in treatment group, which made the distribution of the QOL score wider thus increasing statistical power in testing the association between the QOL and BPV. There is a possibility that forest therapy intervention had favorable effect on BPV, although the control group also showed nonspecific increase of the QOL, diluting the between-group difference. Thus, our present result may not be applicable to the general population in the absence of a particular intervention designed for improving QOL. Larger scale interventional study may be needed to confirm that improvement of the QOL can lead to decreased BPV.

We do not have detailed information on medications used by the study subjects, which is a significant limitation because antihypertensive medication is known to have some influence on BPV.3,4 However, because we excluded patients who needed regimen change during the study period, confounding by the medication effect could be minimized. Subjects with medication showed larger BPV than those who were not in pharmacological treatment. While previous studies showed antihypertensive agents usually decreasing BPV with some difference between the antihypertensive agent classes, comparison of BPV between the medicated hypertensive group and non-medicated less severe hypertensive group has not been done. Considering that the baseline SBP did not differ significantly between medicated and non-medicated group (medicated 132±15 mm Hg vs. non-medicated 136±16 mm Hg, p=0.47), non-medicated group probably had less severe hypertension than medicated group, which may be a possible reason why they had less variability in blood pressures.

There are several other limitations in this study. This study was not originally designed to evaluate the relationship between QOL and BPV, but as a clinical trial to evaluate the effect of behavioral intervention. Larger-scale study is needed to confirm the study finding. A behavioral intervention trial has inherent difficulty in randomization because patients' willingness to participate is crucial for proper application of the experimental treatment. Our trial also has that limitation. However, because the effect of forest therapy program is not a main focus of this study, we think that this convenient and non-random assignment may not have crucial influence on the study result. Sample size was small, including only patients with mild hypertension.

In conclusion, blood pressure variability has significant association with the QOL in a small group of mildly hypertensive patients. Improvement of QOL may induce favorable change in blood pressure variability.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Scattergram showing the association between blood pressure variability [coefficient of variation of systolic blood pressure (CV of SBP)] and the total score of quality of life. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial support came from 'Forest Science & Technology Projects (S11113L020100)' from Korea Forest Service (PI, Woo).

References

1. Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Metoki H, Asayama K, Hara A, Obara T, et al. Day-by-day variability of blood pressure and heart rate at home as a novel predictor of prognosis: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2008; 52:1045–1050.

2. Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Dolan E, O'Brien E, Dobson JE, Dahlöf B, et al. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 2010; 375:895–905.

3. Webb AJ, Fischer U, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM. Effects of antihypertensive-drug class on interindividual variation in blood pressure and risk of stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010; 375:906–915.

4. Zhang Y, Agnoletti D, Safar ME, Blacher J. Effect of antihypertensive agents on blood pressure variability: the Natrilix SR versus candesartan and amlodipine in the reduction of systolic blood pressure in hypertensive patients (X-CELLENT) study. Hypertension. 2011; 58:155–160.

5. Nabe B, Lies A, Pankow W, Kohl FV, Lohmann FW. Determinants of circadian blood pressure rhythm and blood pressure variability in obstructive sleep apnoea. J Sleep Res. 1995; 4(S1):97–101.

6. van den Meiracker AH, Man in 't Veld AJ, van Eck HJ, Wenting GJ, Schalekamp MA. Determinants of short-term blood pressure variability. Effects of bed rest and sensory deprivation in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1988; 1:22–26.

7. Puddey IB, Jenner DA, Beilin LJ, Vandongen R. Alcohol consumption, age and personality characteristics as important determinants of within-subject variability in blood pressure. J Hypertens Suppl. 1988; 6:S617–S619.

8. Serafini G, Pompili M, Innamorati M, Iacorossi G, Cuomo I, Della Vista M, et al. The impact of anxiety, depression, and suicidality on quality of life and functional status of patients with congestive heart failure and hypertension: an observational cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010; 12.

9. Sakakura K, Ishikawa J, Okuno M, Shimada K, Kario K. Exaggerated ambulatory blood pressure variability is associated with cognitive dysfunction in the very elderly and quality of life in the younger elderly. Am J Hypertens. 2007; 20:720–727.

10. Okano Y, Tochikubo O, Umemura S. Relationship between base blood pressure during sleep and health-related quality of life in healthy adults. J Hum Hypertens. 2007; 21:135–140.

11. Sung J, Woo JM, Kim W, Lim SK, Chung EJ. The effect of cognitive behavior therapy-based "forest therapy" program on blood pressure, salivary cortisol level, and quality of life in elderly hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2012; 34:1–7.

12. Kim KY, Chun BY, Kam S, Lee SW, Park KS, Chae SC. [Development of measurement scale for the quality of life in hypertensive patients]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005; 38:61–70.

13. Okano Y, Hirawa N, Tochikubo O, Mizushima S, Fukuhara S, Kihara M, et al. Relationships between diurnal blood pressure variation, physical activity, and health-related QOL. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2004; 26:145–155.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download