Abstract

Purpose

Unexpected requests for non-cardiac surgery requiring discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) frequently occur in daily clinical practice. The objectives of this study were to evaluate prevalence, timing and clinical outcomes of such unexpected requests for non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures during the first year after drug-eluting stents (DESs) implantation.

Materials and Methods

We prospectively investigated the prevalence, timing and clinical outcomes of unexpected requests for non-cardiac surgery or other procedures during the first year after DESs implantation in 2117 patients.

Results

The prevalence of requested non-cardiac surgery or invasive procedures was 14.6% in 310 requests and 12.3% in 261 patients. Among 310 requests, those were proposed in 11.3% <1 month, 30.0% between 1 and 3 months, 36.8% between 4 and 6 months and 21.9% between 7 and 12 months post-DES implantation. The rates of actual discontinuation of DAPT and non-cardiac surgery or procedure finally performed were 35.8% (111 of 310 requests) and 53.2% (165 of 310 requests), respectively. On multivariate regression analysis, the most significant determinants for actual discontinuation of DAPT were Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent implantation with 3-month DAPT (OR=5.54, 95% CI 2.95-10.44, p<0.001) and timing of request (OR=2.84, 95% CI 1.97-4.11, p<0.001). There were no patients with any death, myocardial infarction, or stent thrombosis related with actual discontinuation of DAPT.

Although early discontinuation of clopidogrel has been regarded as a strong predictor for the occurrence of stent thrombosis following drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation, unexpected minor and major operations or other invasive procedures requiring discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) frequently occur in real world daily clinical practice.1-5 Therefore, many advisory groups recommend postponing elective surgery.6,7 However, to date, data on prevalence, timing, and clinical outcomes of unexpected requests for non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures after DES implantation are scarce. Therefore, we used the data from the randomized REal Safety and Efficacy of 3-month dual antiplatelet Therapy following Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent implantation (RESET) trial to prospectively and systematically evaluate the prevalence, timing, and clinical outcomes of unexpected requests for non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures during the first year after DES implantation.

The real safety and efficacy of 3-month DAPT following Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent (E-ZES; Medtronic, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA, USA) implantation trial (RESET trial) was a prospective, open label, randomized trial conducted at 26 sites in Korea.8 The primary goal of this trial was to compare the safety and efficacy of two DES+DAPT implantation strategies: E-ZES+3-month DAPT versus standard therapy (other DES+12-month DAPT). Details regarding study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and primary outcomes were provided in a prior publication.8 All participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive either E-ZES+3-month DAPT (n=1059) or standard therapy (n=1058). After stent implantation, aspirin 100 mg daily was prescribed indefinitely; and the duration of treatment with clopidogrel 75 mg daily was determined according to the assigned randomized strategy. Clinical follow-up was performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after the DES implantation. In the RESET trial if possible at all, it was recommended that elective non-cardiac surgery or procedures with significant risk of bleeding were deferred until the completion of the appropriate DAPT, as recommended in the current guideline regarding the management of the patients treated with DES.6 In addition, for patients who underwent surgery or procedures that required mandatory discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy, aspirin was continued if possible at all.6,7 In the case of high-risk patients who had to undergo surgery or procedures after complete discontinuation of DAPT, early hospital admission for monitoring and surveillance was strongly recommended. All study participants provided written informed consent using documents approved by the institutional review board at each participating center.

Details regarding unexpected requests from various health providers requiring discontinuation of DAPT in order to perform non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures during the first 12 months post-DES implantation were collected using a questionnaire completed by physicians who performed the DES implantation procedures. This questionnaire included 1) reasons for discontinuation of DAPT, 2) exact non-cardiac surgery or invasive procedures that were requested, 3) whether DAPT was actually discontinued, 4) whether the surgical or invasive procedures were performed or deferred, and 5) clinical outcomes of the patients. Discontinuation of DAPT was defined as the discontinuation of any antiplatelet agents in a patient being treated with more than one agent or discontinuation of aspirin in case of aspirin mono-therapy. Surgery or procedures were classified into six categories based on the previous and the current guidelines considering the characteristics of procedures: 1) high-risk operation (aortic, peripheral vascular, or emergent operation); 2) intermediate-risk operation (intraperitoneal and intrathoracic surgery, carotid endarterectomy, head and neck surgery, orthopedic surgery, or prostate surgery); 3) low-risk operation (cataract, breast surgery, or ambulatory surgery); 4) invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, defined as procedures performed under the guidance of fluoroscopy without general anesthesia; 5) dental operation or procedures; and 6) endoscopic operations or procedures without general anesthesia.7,9 For surveillance regarding the duration, use, or discontinuation of DAPT, we used the Korean national healthcare monitoring system that tracks the use of specific drugs in Korea including direct review of patient medical records, phone visits, and personal e-mail contacts. In case of discontinuation of DAPT for unexpected operations or other invasive procedures, the tests of electrocardiogram or cardiac enzymes including early hospital administration before operation or procedures were strongly recommended to monitor the patients' subsequent symptoms or outcomes. The collection of questionaries was done by web-based report system (main way), mail, or telephone-contact.

All analyses were performed on a per-patient and per-request level. In addition, we analyzed the occurrence of the primary endpoint of RESET trial, a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, target-vessel revascularization, or bleeding at 1 year post-procedure.8 Clinical events were defined according to the Academic Research Consortium as published previously.8-10 All requests, questionnaire data, and clinical events were independently monitored and assessed by a Clinical Event Committee.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System software (SAS 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation and compared with analysis of variance. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the major determinants for actual discontinuation of DAPT. Univariate variables with p-value ≤0.05 and other expected factors influencing the actual discontinuation of DAPT or risk factors for the occurrence of stent thrombosis (age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, clinical presentations, types of non-cardiac surgery, stent diameter and length, and multi-vessel intervention or multiple stenting) were entered into the final multivariate logistic regression model. p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

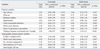

A brief summary of baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics in patients with or without unexpected requests for non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures is shown in Table 1. Of the patients requested for operation or invasive procedures (n=261), there was no patient with oral anticoagulant besides the antiplatelets such as aspirin or clopidogrel. Overall, there were 310 requests for non-cardiac surgery or invasive procedures requiring premature discontinuation of DAPT in 261 patients (12.3%); 2.0% of patients had more than one request to prematurely discontinue DAPT (Table 2). Among the 310 requests, 11.3% were <1 month post-DES, 30.0% were between 1 and 3 months post-DES, 36.8% were between 4 and 6 months post-DES, and were 21.9% between 7 and 12 months post-DES implantation. The types of procedures are also listed in Table 2; only 6 (1.9%) were high-risk and 60 (19.4%) were intermediate-risk.

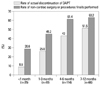

On the per-request level analysis, the rate of actual discontinuation of DAPT was 35.8% (111 of 310 requests). Only 53.2% (165 of 310 requests) procedures were actually performed. The remaining 145 (46.8%) procedures were postponed until >1 year after DES implantation. In 54 instances, procedures were performed without discontinuation of DAPT; no high-risk operation, 4 intermediate-risk, and 2 low-risk operation; 4 invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures; 19 dental operation or procedures; and 25 endoscopic operations or procedures. The types of procedures finally performed are shown in Table 3. The rate of actual discontinuation of DAPT and the frequency of procedures actually performed according to follow-up intervals from DES implantation are presented at Fig. 1. The rates of actual discontinuation of DAPT (p<0.001) and the rate of non-cardiac surgery or procedures finally performed (p=0.001) according to the timing of requests were significantly different.

On multivariate logistic regression analysis, the most significant determinants for actual discontinuation of DAPT were E-ZES+3-month DAPT (odds ratio=5.54, 95% confidence interval 2.95 to 10.44, p<0.001) and timing of request (odds ratio=2.84, 95% confidence interval 1.97 to 4.11, p<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 5 summarizes clinical outcomes. There were no deaths, myocardial infarctions, or stent thromboses related to actual discontinuation of DAPT in the setting of non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures.

The main findings of this systematic and prospective analysis were as follows: 1) there was a 14.6% rate of unexpected requests for discontinuation of DAPT because of unanticipated need for non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures in 12.3% of patients during the first 12 months after DES implantation. 2) On a per-request level, procedures were finally performed in about half of the requested cases (7.8%) with actual discontinuation of DAPT in approximately one-third of the requests. 3) Favorable clinical outcomes were observed in patients regardless of whether or not DAPT was discontinued or a procedure actually performed. Because patients with planned non-cardiac surgery or invasive procedures were excluded from the RESET trial before randomization, these requests for non-cardiac surgery and invasive procedures after DES implantation in this study were completely unexpected.

A first small study of 40 bare-metal stent-treated patients revealed an extraordinarily high incidence of catastrophic perioperative complications (34% mortality) in patients who underwent elective or semi-elective non-cardiac surgery soon after stent implantation.11 In the DES era, the reported risk associated with major non-cardiac surgery varied widely from 0% to 22%, with most studies reporting a risk ≤6% in retrospective studies.12 In most studies, a longer time interval between DES implantation and non-cardiac surgery was found to be associated with a lower risk of perioperative complications.12-14 Accordingly, the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommended delaying non-cardiac surgery for 12 months after implantation of DES.6,7,12

Compared to the previous studies,11,12 the current study showed favorable clinical outcomes even in patients in whom DAPT was discontinued and surgery or an invasive procedure actually performed. However, this is a prospective, randomized study in which patients with planned procedures were completely excluded before randomization. Second, E-ZES was used in half of study participants; sufficient stent strut neointimal coverage in the early stage following E-ZES implantation might have played a protective role against the occurrence of stent thrombosis in the situation of actual discontinuation of DAPT.8,15,16 Third, second-generation DESs - that have more favorable clinical outcomes, drug-release kinetics, and polymer characteristics than first-generation DES17,18 - were also frequently used in the standard therapy group. Fourth, the number of patients receiving the requests of DAPT discontinuation was small. Especially, the rate of high-risk operation out of all non-cardiac surgery or procedures proposed was low in this study. All these factors might have contributed to the favorable clinical outcomes in patients with actual discontinuation of DAPT who underwent non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures.

A recent retrospective registry of 4637 patients showed that the incidence of major non-cardiac surgery was 4.4% within 1 year after DES implantation, and that the risk of composite outcome of cardiac death, myocardial infarction, or stent thrombosis increased 27-fold in the week following non-cardiac surgery compared with any other week after stent implantation.19 Data from the same registry revealed that minor surgery was performed in 2.0% of 8323 DES-treated patients.12 Another systematic analysis revealed that 26% of 11151 patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention also underwent at least 1 non-cardiac surgery during the 5 years after index procedures; 23% orthopedic, 20% abdominal, 12% urologic, 10% vascular, and 35% others.20 However, the procedures in this study were high-risk operation in 3.0%, intermediate-risk operation in 22.4%, low-risk operation in 3.0%, invasive procedures and non-surgical in 4.8%, dental surgery or procedures in 27.3%, and endoscopic surgery or procedures in 39.4%.

In the current study, there were 310 unanticipated requests (14.6%) and 165 procedures (7.8%) actually performed. Thus, the need for non-cardiac surgery and invasive procedures normally associated with premature discontinuation of DAPT could be more frequent than expected after DES implantation. Individual patient risk stratification should be assessed before DES implantation, especially in older patients.20 For each 10-year increase in age, there was a 1.3-fold increase in the incidence of non-cardiac surgery (p<0.0001) (about 15% in ages <50 years and more than 30% in ages >70 years).20

This study has limitations. First, the analysis was performed using random study data with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria and close patient follow-up typical of a randomized trial. Therefore, the results of this study may not apply to patients with clinically unstable presentation and angiographically more complex lesion subsets that are treated in real-world settings. In addition, because the patients with planned procedures were completely excluded in this study, the clinical outcomes of this subset could not be known from RESET study. Second, because the number of patients with actual DAPT discontinuation was small, a long-term data with a large population are needed. Finally, although the analyses on the detailed reasons for postponing or actually performing operation or procedures irrespective of the discontinuation of DAPT are important for the understanding of the general management of the patients with DES, we could not perform these analyses because of lack of data regarding the reasons for the final physicians' decisions.

In conclusion, the requests for unexpected non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedure typically requiring premature discontinuation of DAPT could be more frequent than expected. However, approximately half of these procedures were not performed at the time of request. Nevertheless, actual discontinuation of DAPT and non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures did not contribute to an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events including death, myocardial infarction, or stent thrombosis in the patients enrolled in the RESET trial.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Rate of actual discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) and non-cardiac surgery or other invasive procedures finally performed on patients with requests according to the follow-up intervals from DES implantation. The numbers outside the boxes represent the rates of actual discontinuation of DAPT and surgery or procedures finally performed. DES, drug-eluting stent.

Table 2

Unexpected Requests for Discontinuation of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy due to Non-Cardiac Surgery or Other Invasive Procedures

Table 3

Types of Non-Cardiac Surgery or Other Invasive Procedures Finally Performed and the Actual Use of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy during Non-Cardiac Surgery or Other Invasive Procedures

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Cardiovascular Research Center, Seoul, Korea, Medtronic Inc. and grants from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (No. A085012 and A102064), the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (No. A085136).

References

1. Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, Ge L, Sangiorgi GM, Stankovic G, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA. 2005; 293:2126–2130.

2. Spertus JA, Kettelkamp R, Vance C, Decker C, Jones PG, Rumsfeld JS, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of premature discontinuation of thienopyridine therapy after drug-eluting stent placement: results from the PREMIER registry. Circulation. 2006; 113:2803–2809.

3. Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Buser PT, Rickenbacher P, Hunziker P, Mueller C, et al. Late clinical events after clopidogrel discontinuation may limit the benefit of drug-eluting stents: an observational study of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006; 48:2584–2591.

4. Brar SS, Kim J, Brar SK, Zadegan R, Ree M, Liu IL, et al. Long-term outcomes by clopidogrel duration and stent type in a diabetic population with de novo coronary artery lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 51:2220–2227.

5. Ferreira-González I, Marsal JR, Ribera A, Permanyer-Miralda G, García-Del Blanco B, Martí G, et al. Background, incidence, and predictors of antiplatelet therapy discontinuation during the first year after drug-eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2010; 122:1017–1025.

6. Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr, Gardner TJ, Lockhart PB, Moliterno DJ, et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, American College of Surgeons, and American Dental Association, with representation from the American College of Physicians. Circulation. 2007; 115:813–818.

7. Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, Calkins H, Chaikof E, Fleischmann KE, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery): Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2007; 116:1971–1996.

8. Kim BK, Hong MK, Shin DH, Nam CM, Kim JS, Ko YG, et al. A new strategy for discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy: the RESET Trial (REal Safety and Efficacy of 3-month dual antiplatelet Therapy following Endeavor zotarolimus-eluting stent implantation). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012; 60:1340–1348.

9. Task Force for Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Perioperative Cardiac Management in Non-cardiac Surgery. European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Boersma E, De Hert S, et al. Guidelines for pre-operative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative cardiac management in non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2009; 30:2769–2812.

10. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007; 115:2344–2351.

11. Kałuza GL, Joseph J, Lee JR, Raizner ME, Raizner AE. Catastrophic outcomes of noncardiac surgery soon after coronary stenting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000; 35:1288–1294.

12. Brilakis ES, Cohen DJ, Kleiman NS, Pencina M, Nassif D, Saucedo J, et al. Incidence and clinical outcome of minor surgery in the year after drug-eluting stent implantation: results from the Evaluation of Drug-Eluting Stents and Ischemic Events Registry. Am Heart J. 2011; 161:360–366.

13. Schouten O, van Domburg RT, Bax JJ, de Jaegere PJ, Dunkelgrun M, Feringa HH, et al. Noncardiac surgery after coronary stenting: early surgery and interruption of antiplatelet therapy are associated with an increase in major adverse cardiac events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49:122–124.

14. Anwaruddin S, Askari AT, Saudye H, Batizy L, Houghtaling PL, Alamoudi M, et al. Characterization of post-operative risk associated with prior drug-eluting stent use. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009; 2:542–549.

15. Kim JS, Jang IK, Fan C, Kim TH, Kim JS, Park SM, et al. Evaluation in 3 months duration of neointimal coverage after zotarolimus-eluting stent implantation by optical coherence tomography: the ENDEAVOR OCT trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009; 2:1240–1247.

16. Lee SY, Hong M. Stent evaluation with optical coherence tomography. Yonsei Med J. 2013; 54:1075–1083.

17. Stone GW, Rizvi A, Newman W, Mastali K, Wang JC, Caputo R, et al. Everolimus-eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:1663–1674.

18. Meredith IT, Worthley S, Whitbourn R, Walters DL, McClean D, Horrigan M, et al. Clinical and angiographic results with the next-generation resolute stent system: a prospective, multicenter, first-in-human trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009; 2:977–985.

19. Berger PB, Kleiman NS, Pencina MJ, Hsieh WH, Steinhubl SR, Jeremias A, et al. Frequency of major noncardiac surgery and subsequent adverse events in the year after drug-eluting stent placement results from the EVENT (Evaluation of Drug-Eluting Stents and Ischemic Events) Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010; 3:920–927.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download