Abstract

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is an uncommon disorder, and usually affects young men and has a benign course. Common triggers are asthma, the smoking of illicit drugs, the Valsalva maneuver, and respiratory infections. Most cases are usually due to alveolar rupture into the pulmonary interstitium caused by excess pressure. The air dissects to the hilum along the peribronchovascular sheaths and spreads into the mediastinum. However, pneumomediastinum following pharyngeal perforation is very rare, and has only been reported in relation to dental procedures, head and neck surgery, or trauma. We report a case of pneumomediastinum that developed in a 43-year-old patient with pharyngeal perforation after shouting. His course was complicated by mediastinitis and parapneumonic effusions.

Pneumomediastinum is defined as the presence of air within the mediastinum. It can occur as a result of trauma, iatrogenic complication, pathologic process of pulmonary disease or spontaneously. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM) is a very uncommon disorder1 that accounts for approximately 1 in 30000 emergency department presentations annually.2 SPM usually affects healthy young men with no underlying disease, and has been associated with severe acute asthma, drug inhalation, coughing, delivery, and exercise. SPM most commonly presents with chest pain and dyspnea. It typically has a benign course and is self-limited, but there have been cases of pneumothorax and mediastinitis occurring as a complication.

We describe a case of pneumomediastinum following pharyngeal perforation after shouting with subsequent mediastinitis and parapneumonic effusions.

A 43-year-old man presented with a 2-day history of dyspnea and chest pain after shouting in a quarrel with his wife. He had presented to a local clinic with fever, cough, sputum, and odynophagia 3 days previously, and was treated for acute pharyngitis. Before the onset of symptoms, he was in good health and had no significant past medical history except for 50 pack-years smoking history. Vital signs on admission were blood pressure 120/70 mm Hg, heart rate 100/min, respiration rate 28/min, and body temperature 38.7℃. On physical examination, there was swelling and tenderness in the left cervical area. Crackles were noted in both cervical areas. Coarse breath sounds were noted in both lung fields, and crackles were noted in the left lower lung field.

Leukocyte count was 13000/mm3 (85.2% neutrophils, 9.4% lymphocytes, 4.7% monocytes, 0.2% eosinophils), hemoglobin 13.0 g/dL, and platelet count 229000/mm3. The results of arterial blood gas analysis in room air were pH 7.491, PaCO2 25.2 mm Hg, PaO2 62.4 mm Hg, HCO3- 21.8 mmol/L, and SaO2 94.2%. Liver function tests were normal. Serum total protein was 6.5 g/dL, albumin 3.5 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen 20.0 mg/dL, creatinine 1.2 mg/dL, sodium 135 mmol/L, potassium 4.2 mmol/L, creatine phosphokinase 431 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase 658 IU/L, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein 30.7 mg/dL. Urinalysis was normal.

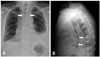

An initial chest radiography showed linear air trapping parallel to the border of the trachea, bilateral pleural effusion that was more severe on the left side, and consolidations in both lower lungs (Fig. 1). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed air collection around the airway and mediastinum, infiltration around the mediastinum, and bilateral pleural effusions (Fig. 2A and B).

Laryngoscopy was performed by an otolaryngologist, and a small pharyngeal perforation in the right side of the vallecula was seen. A cervical CT scan also showed lacerations in the same area (Fig. 2C). Analysis of the pleural fluid on the left side was consistent with parapneumonic effusions (pH 8.0, red blood cell count 3840/mm3, white blood cell count 2880/mm3, neutrophils 95%, total protein 4.6 g/dL, albumin 2.5 g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 27198 IU/L, glucose 27 mg/dL). Intravenous moxifloxacin was started. In addition, chest tubes were inserted on both sides and supplemental oxygen was administered. Laryngoscopy was repeated 2 days later, and the previously-noted small pharyngeal perforation was not seen. Blood and pleural fluid cultures were negative, but fever and leukocytosis persisted. Antibiotics were broadened to piperacillin-tazobactam and amikacin. Fifteen days after admission, a follow-up chest radiography showed resolution of air trapping around the mediastinum and regression of parapneumonic effusions. The patient's symptoms and laboratory results continuously improved, and the patient was discharged 29 days after admission.

Pneumomediastinum as a medical entity was first described in 1819 by Laennec3 in the setting of traumatic injury, and spontaneous pneumomediastinum was first reported in 1939 by Hamman.4 It was defined as the presence of interstitial air in the mediastinum without any apparent precipitating factor.

Causes of pneumomediastinum include severe acute asthma, the use of mechanical ventilation, the inhalation of illicit drugs, exercise, and increased intra-abdominal pressure due to coughing or shouting.5,6 The pathophysiology of this condition was initially described based on animal experiments by Macklin and Macklin7 in 1944. Increased alveolar pressure or decreased perivascular interstitial pressure can cause terminal alveolar rupture, leading to accumulation of air in the interstitium of the lung. The air then dissects to the hilum and subsequently the mediastinum along the pressure gradient.8 Pneumomediastinum can also be caused by pharyngeal perforation during dental procedures or head and neck surgery.9 Perforation of the trachea or esophagus can also lead to the development of pneumomediastinum. Under these conditions, pneumomediastinum develops due to air leakage through the perforation site. The main causes of perforation are trauma and intubation. Spontaneous perforation of the pharynx, trachea, or esophagus is unusual.10,11

In the present case, pneumomediastinum was thought to have developed from the pharyngeal perforation and laceration found in laryngoscopy and cervical CT scan. A sudden pressure increase in the pharynx during shouting in the setting of pharyngitis might have caused tearing of the anterior pharyngeal wall.

Diagnosis of pneumomediastinum is usually made with chest radiography. It is important to examine the lateral views, because 50% of all cases may remain undiagnosed if only a posteroanterior film is taken.12 Chest CT should be performed when there is a clinical suspicion and negative chest radiography.

In general, the course of pneumomediastinum is one of fast recovery with conservative treatment. There are no consensus guidelines regarding the treatment. Typically, therapy includes rest, oxygen, analgesia and suppression of hyperventilation. Breathing 100% oxygen will enhance reabsorption of the free air by increasing the nitrogen gradient between the alveoli and the tissues.13 Pain usually resolves one or two days after the onset of pneumomediastinum, and chest radiography usually normalizes within 1 week.

In our case, mediastinitis and bilateral pleural effusions accompanied pneumomediastinum. We believe that the infection spread through the pharyngeal laceration and pneumomediastinum, and subsequently developed into mediastinitis and parapneumonic effusions. In descending mediastinitis, broad-spectrum aerobic and anaerobic antibiotic coverage is mandatory because the majority of infections are polymicrobial with aerobic and anaerobic bacterial species.14

This report highlights another potential cause of pneumomediastinum. In a patient with pharyngitis who develops pneumomediastinum after shouting, pharyngeal perforation should be considered as a cause. Physicians should be aware of possible complications, including mediastinitis and parapneumonic effusions.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Posteroanterior chest X-ray showing linear air trapping parallel to the border of the trachea (arrows), bilateral pleural effusions with consolidation in both lower lungs that was more severe on the left side. (B) Lateral chest X-ray showing a streak of air outlining the posterior pericardium as well as portions of the descending thoracic aorta (arrows).

References

1. Panacek EA, Singer AJ, Sherman BW, Prescott A, Rutherford WF. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: clinical and natural history. Ann Emerg Med. 1992; 21:1222–1227.

2. Newcomb AE, Clarke CP. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a benign curiosity or a significant problem? Chest. 2005; 128:3298–3302.

3. Laennec RT. A treatise on disease of the chest and on mediate auscultation. 2nd ed. London: T and G Underwood;1827.

4. Hamman L. Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1939; 64:1–21.

5. Chalumeau M, Le Clainche L, Sayeg N, Sannier N, Michel JL, Marianowski R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001; 31:67–75.

6. Shine NP, Lacy P, Conlon B, McShane D. Spontaneous retropharyngeal and cervical emphysema: a rare singer's injury. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005; 84:726–727.

7. Macklin MT, Macklin CC. Malignant interstitial emphysema of lungs and mediastinum as an important occult complication in many respiratory diseases and other conditions: an interpretation of the clinical literature in the light of laboratory experiment. Medicine. 1944; 23:281–358.

8. Maunder RJ, Pierson DJ, Hudson LD. Subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Arch Intern Med. 1984; 144:1447–1453.

9. Torres-Melero J, Arias-Diaz J, Balibrea JL. Pneumomediastinum secondary to use of a high speed air turbine drill during a dental extraction. Thorax. 1996; 51:339–341.

10. Bodenez C, Houliat T, Lacher Fougère S, Traissac L. [Spontaneous cervical emphysema: a case report] . Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 2003; 124:195–198.

11. Rousié C, Van Damme H, Radermecker MA, Reginster P, Tecqmenne C, Limet R. Spontaneous tracheal rupture: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2004; 104:204–208.

12. Ba-Ssalamah A, Schima W, Umek W, Herold CJ. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Eur Radiol. 1999; 9:724–727.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download